Political cartoons are the final word in man’s search for metaphor. Writers, the poor dears, struggle for the right words to make the reader see a situation. A writer might labor with the joke that George Bush swung from trees, proving Darwin was right — we are descended from apes — or refer to the White House as a petting zoo. An economist might dramatize his predictions, saying we are indeed balanced on the knife-edge of a fiscal machete. Political analysts describe verbal pictures to make their concepts clear, to illustrate while they explain. All these metaphors, and their illegitimate spawn, similes, exist to make readers remember a vision drawn from something they have actually seen physically. We hear of corporations and the stock market getting a “haircut” when they give up a portion of their earnings. We hear of real estate being “under water” if more is owed than anyone would pay.

A political drawing dispenses with the search for words. It goes right for the main receptor of metaphor: the eye. A Wall Streeter is missing part of his hair, or suffers a major trepanation from the brow line up. A house is drawn with fish swimming by. If a family is sitting down to dinner inside, the effect is even stronger. The poor suckers obviously don’t know how bad things are.

Mixed metaphors, the bane of writing purists, are no problem for political art. The New Yorker feature, “Block that Metaphor,” caught things like “milking the well of human kindness,” and such mix-ups. But in the magazine’s cartoons a blend of metaphors was just fine. Smushed metaphors abound. Impossible and highly implausible situations are welcome. A bull in a bar having a drink next to a bear asks for investing advice. Mild but amusing. Or the bull walks into a pawnshop to buy back his saxophone, announcing he is quitting finance. And so on.

Cartoonists appreciate a good silly rouser, or a pun that is at least 10 percent germane. But from time to time political cartoonists like to be taken seriously. American readers are born with the conviction that cartoons are supposed to be humorous, a lineage coming directly from Saturday morning television. Anything subtle or threatening is troubling and out of place, like ice cream at a funeral. Such work troubles editors. A cartoonist is urged to stick as close as possible to the obvious and harmless. In some minds the worst thing that can be said about a cartoon is “that’s mean!”

Generally journalists don’t trust their audience to understand the seriousness of the world out there. Readers are presumed to expect broad humor in a cartoon and to have only the most basic sense of what is funny. But when drawn with serious intent and taken seriously, political artwork can be far more effective, and scarier, than words. There are allowable violations of fair comment. A blunt edge to the weaponry. For example, to get the point across political cartoons contain a good deal of graphic shorthand. Slaughter is rendered as piles of skulls, even if such piles did not actually exist. Dictators — Saddam, Khadafy, Assad — probably didn’t personally kill anyone. But they are portrayed with smoking machine guns even so. Some readers still look for the funny part.

Turner Catledge, a transformative editor at the New York Times, said that his paper did not have a cartoonist because the messages (and I think he meant the metaphors) could not be qualified. That is, the artwork cannot be shaded to allow for less bombastic depictions, or to hint at a lack of surety, or to present an alternative view. His explanation (as I have received it) was (in effect) that in any New York Times editorial, about halfway down you will see a paragraph beginning with the word, “however.” There is no way to put “however” in a cartoon.

Political artists, from Daumier on, have regarded that as a selling point. It’s not that you can’t shade the meaning, but rather that in cartoons no one expects you to. Perhaps no one wants you to. Adverbs, the main crutch of columnists on deadline, are the enemy of truth. Political writing, particularly in English (as Orwell famously pointed out), is well equipped to dilute and avoid direct blame-fixing. A significant portion of American journalism — both reporting and opinion — would be mute without the word “may.” “Higher gas prices may be in our future.” You can’t get any more accurate than that. “It may rain tomorrow.”

But in a cartoon, if a president drives the economy over a cliff (although others have drawn this, I have not . . . yet) there is no “may” about it. This is a cartoon cliff, in all its metaphoric threatening simplicity. The drawing doesn’t just predict disaster; it is dead certain of disaster. Often wrong, but never in doubt. Depending on the opinion of the various editors involved, such absolutes are allowable even if not factual. Later on in these pages a cartoon is included showing the smoldering remains of the White House as George Bush remarks to Cheney that it is time to “pass the torch.” The suggestion that the Bush administration burned the place down is coupled with the ringing John F. Kennedy line.

The Purpose and Role of Political Art

Many American newspapers often fall into the same habit as popular history. Popular historians, those hoping to sell many copies of their new look at MacArthur or Truman or, God help us, Lincoln, often leave the historian role and become enthusiasts. Book buyers who are infatuated with the heroic life of Dwight Eisenhower for example are not going to buy books that show him to be less than a hero. They certainly are not going to want him shown as a confused leader who stammered and stumbled through his presidency. If research shows that he actually did stammer and stumble (and Eisenhower admitted as much) the book won’t sell. No one wants to see his happy rear view opinion clouded.

Newspapers commit the same minor crime. They are enthusiastic about news being important, especially the news they have that day. A good percentage no longer take a strong political view dictated by their owners. They avoid outright advocacy or condemnation. Their owners are now corporations, faceless and bland, more interested in publishing something they call “product” than the news.

So political art, like the writing in many papers, has been scaled back, dampened, and qualified. Newspapers are largely reporting on daily events, and the conclusion of what those events actually mean in the long run is not known. Anything that sounds like a conclusion, or a prediction, is voiced in only moderately conclusive tones. It’s embarrassing to have to issue corrections for definite statements in yesterday’s paper, and easier not to make any in the first place. Two exceptions to this rule of course are sports and the stock market, two places where no one is really expected to know what is going to happen. In drawings, however, if a conclusion is reached or even hinted at, it more or less stands there by itself. It’s difficult to perform a retraction or qualification the next day. Fortunately no one expects that an artistic outrage must be defended.

Good Drawing

Good artwork is like a practiced writing style. Again, the strength comes from the relationship between skill and message. We can use some of the best-known columnists as examples. George Will’s columns are criticized by many as to their logic and emphasis, but most agree that his writing is intelligent, educated, well edited and, if the term can be used, manicured. When he rises from mere arch chagrin to full-blown anger, the quality rather than the heat of the steaming paragraphs seem to bolster his conclusions, in the same way a well-dressed salesman seems more persuasive.

Writing relies on the mastery of, or at least a familiarity with, several basic areas of language dexterity, and is strengthened by things like sentence structure, usage, argumentation, tone, and the expository order of support. Added to these are smaller considerations such as vocabulary, style, and respect for the reader’s span of concentration. In drawing, the elements (in rough parallel) are anatomy (both animal and human), perspective and foreshortening, texture, and a quality I’ll call (for want of a better term) fall-of-light. In the same way that good writing can make a reader visualize something with words, good drawing makes an observer see something with several lines, a few scratches here and there, a single line that outlines a profile, an arch of upper lip in a grimace, or the high contrast of a face in glaring desert sunlight. The interior of a jail cell, if the intention is that it be miserable and confining, must have walls that look solid and are clearly made of unbreachable concrete. And in the same way that economy of words is important, so is economy of line. The great World War II British cartoonist David Low said that after he finished a cartoon he would take up his brush and white paint and white out everything that was not essential.

Most political art is done on deadline, reflecting emerging events. The rendering and composition is done out of the artist’s memory since there is not time to go out and find the proper scene, or make actual people act as models. Many times artists fall back on what they know how to draw because they have drawn it many times before. This results in a tendentiousness that is not always bad, but sometimes is. Caricature is an example. Cartoonists get into the habit of using the same telltale features for well-known politicians as convenient shorthand. This is done to meet deadlines, but also from laziness.

Most political art is done on deadline, reflecting emerging events. The rendering and composition is done out of the artist’s memory since there is not time to go out and find the proper scene, or make actual people act as models. Many times artists fall back on what they know how to draw because they have drawn it many times before. This results in a tendentiousness that is not always bad, but sometimes is. Caricature is an example. Cartoonists get into the habit of using the same telltale features for well-known politicians as convenient shorthand. This is done to meet deadlines, but also from laziness.

Working from the mind’s eye rather than the actual eye limits subject matter, because the mind only has a certain number of images stored. It takes an extra effort to try something new, to look at a subject differently, and to take the chance that the result will not work out. The writer John Hersey was credited with never writing the same book twice, not even the same type of book. This sounds patently obvious, but is actually more challenging than it appears. The artist John Singer Sargent was reputed to pick the place he set up his easel by turning around with his eyes closed. He avoided the temptation to choose the easiest view. Both were master of their crafts and were able to write and paint in whatever way and from whatever angle presented itself. But it is also possible that they obtained more universal mastery by setting ever more difficult assignments for themselves.

Choosing a difficult viewpoint, not only graphically but also politically, is sometimes a stretch. Graphic novels are a good example. In graphic novels, which must show the same scene with each change of dialogue, artists are forced to move the viewpoint repeatedly, around the room, from the next room, first close up and then from a distance. This effort, to keep the artwork intriguing, is laborious but rewarding. The reward, after a number of failures, is success and the advancement to a new level of graphic artistry. This sounds high-minded and preachy, and it is both of those things. On the other hand, self-improvement and pride of workmanship is one of the great replacements for high financial return. And that’s a good thing because cartooning doesn’t actually pay that much. Or didn’t you know that?

In many cases the goal is not just good art, that is to say, not good drawing. Some feel that the drawing should not exhibit draftsmanship or the effects of traditional art training. Rather it should be individualistic and a little crazy. It should reflect a unique line and style. Since cartooning, even at the most mordant level, has to take a fundamentally humorous approach, a bit of bizarre in the drawing will issue a warning against seriousness. It’s not true in all cases of course. Tom Toles, of the Washington Post, has a style of almost childlike simplicity, but his meaning is so well-informed, and sometimes so vicious, that the effect is compounded rather than lessened. It is possible to be childlike and vicious. Ask any parent.

The drawing in some political cartoons is simply lousy, which abuses the tolerance some artists are allowed if their style is awkward and clunky. Basic amateur attempts are wonderful if done by striving amateurs. But after a certain time it’s reasonable to expect improvement. In writing, drawing, and music, the expectations are about the same as they are for athletics. After a certain point participants should get good or try something else. In the American mind, however, bad writing, bad art, and even bad music get confused with the value we put on individual expression. Not being able to carry a tune is credited as a revolt against the oppression of harmony.

More preachiness. There’s a Latin proverb, ars est celare artem, which roughly means that the true art is to hide art. The real art, the trick of it, is to do it so well that the means are not visible. The extended philosophy is that a painting should look like the real thing, not like paint on canvas; a sculpture should look like a real person, not like stone; and a drawing should be so convincing that the eye forgets it is seeing some ink lines on paper. A really well made movie is transporting, so that the audience forgets that there is a projector behind and a screen before it, and that the whole thing has been staged. The audience — readers, viewers, listeners — should be convinced of the message because the work of the artist is so skillfully done that the mechanics of it are hidden. Writers, dramatists, and musicians go for the same effect. To get to that level of skill takes time, and dedication, and a willingness to conceal how clever you are.

The argument against this effort is that the work of a man’s hand should look like what it is, and show the individual means, marks, and flaws of the artist. If he is a poor draftsman, well, so what? He has as much right to draw as someone more skilled. And after all, if people like it, he is successful. Cartooning is a commercial activity even if most of the recompense is paid in self-satisfaction. Some would argue that in political art the message is more important than the art, so that whatever way the political argument can be effectively made is obviously the way it should be made. It is analogous to military music – it may not be good, but if it makes you feel like marching off to war, it serves its purpose.

The argument against this effort is that the work of a man’s hand should look like what it is, and show the individual means, marks, and flaws of the artist. If he is a poor draftsman, well, so what? He has as much right to draw as someone more skilled. And after all, if people like it, he is successful. Cartooning is a commercial activity even if most of the recompense is paid in self-satisfaction. Some would argue that in political art the message is more important than the art, so that whatever way the political argument can be effectively made is obviously the way it should be made. It is analogous to military music – it may not be good, but if it makes you feel like marching off to war, it serves its purpose.

Whose Fault Is All This?

Mention was made of the unfortunate role of Saturday morning television on what people think of when they hear the word cartoons. If there’s blame for the current state of cartooning it probably originated a long time ago with Hanna and Barbera and their pathetic imitators. Both men began as traditional animators for MGM, then left to form their own studio. Somewhere it occurred to them that television viewers were unreliable in their dedication to quality. Their designs were painfully simple, and their artwork could be referred to as reductionist. They produced great quantity and minor quality. Reductions in artistic skill meant reduction in costs. And the great gaping maw of television had to be fed so parents could sleep late. These cartoons were so awful, derivative, flat, and moronic that the standard for animation fell precipitously. Newspaper editors sadly determined their standards from television. If the quality in all other forms of cartooning degenerated, why not political cartoons as well?

Digital animation seems to have corrected much of this decline. Feature length animations are rich in texture and realistic action. The writing for these pictures has improved markedly, since the budgets are so gigantic many producers refuse to take a chance on a poorly written concept. And trailing along behind, the audience is developing a sharper sense of what makes one animation studio better than another. Trailing further behind are newspaper and magazine publishers who, no matter how much it hurts, now consider something besides costs.

Fantasy

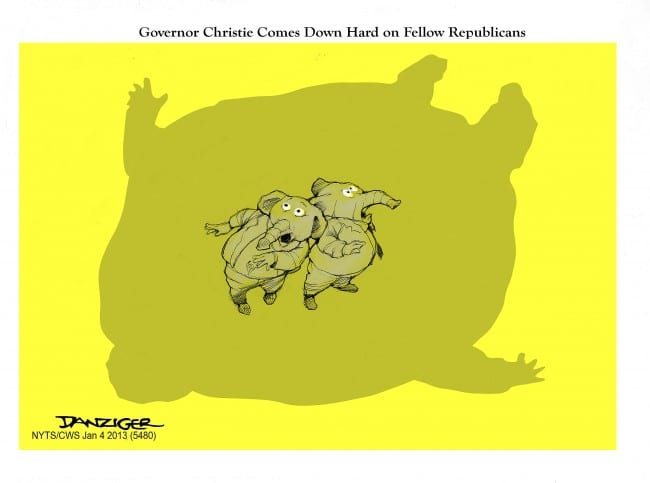

The main strength of nearly all cartooning is fantasy. Most of the successful comic strips are fantastic, even if, as in many cases, the fantasy is that the characters never grow older. (In some cases they do not grow older even after their creators are dead.) The greatest fantasy is, of course, talking animals. Added to that are little kids who talk like adults and regularly pass out sarcasm and philosophy beyond their years. Political cartoons take this a step further. Fantastic situations are composed that seem to reflect the daily electoral passions and tribal conflict. A figure labeled “China” writes checks that turn into belts of machine-gun ammunition. Karl Rove pops out of George Bush’s head where he has been directing things. In a great cartoon by Paul Conrad, Nixon nailed himself to a cross.

The fantasy takes a sinister turn to imagine something violent that happened but was not photographed. An example is the murder of the Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, shot by Putin’s thugs in the hall of her apartment building. The illustration is the moment after the killing and the reader is forced to look at it as the shooters run down the stairs. The scene is therefore semifantasy, a re-creation, but, since she was dead, and someone shot her, it might have happened that way. It’s important to say that such imagining is not to amuse, but rather to fix the image in the mind, more strongly than mere words could. There’s an outside chance Putin may not have had anything to do with it, the murders may have been simple robbers, or she may have shot herself. The reader won’t be sure, but will remember the might-have-been.

An additional advantage of the political illustration is that it delivers its message all at once. Like a well-composed political poster (an art form respected in Europe, but unknown in this country), the image must jump at the reader. Some cartoons are in the moment just before something happens. Some are in the moment just after. The remaining or missing bit of the action must be supplied by the reader.

Timing is important in all things, and desperately so in comedy. Even in trenchant comedy, the joke must arrive just at the right point. It is telling that many cartoonists go on to try their hand at writing plays, and some are successful. Jules Feiffer is probably the best example. Dramatists know that time and attention spans are limited. An audience, even one that has paid good money for a seat, will start to think of other things. A drawing must set the stage, put in the characters, make them say or do something quickly and clearly, before the interval. It’s good training for film directors, too. But the piece of time occupied by the cartoon, especially a sequence of cartoons, depends as much on the reader as on the creator.

Timing is important in all things, and desperately so in comedy. Even in trenchant comedy, the joke must arrive just at the right point. It is telling that many cartoonists go on to try their hand at writing plays, and some are successful. Jules Feiffer is probably the best example. Dramatists know that time and attention spans are limited. An audience, even one that has paid good money for a seat, will start to think of other things. A drawing must set the stage, put in the characters, make them say or do something quickly and clearly, before the interval. It’s good training for film directors, too. But the piece of time occupied by the cartoon, especially a sequence of cartoons, depends as much on the reader as on the creator.

In some cases the reader must bring as much understanding of timing, speed, mass, and physical action to the cartoon. A phrase recently coined here in the land of the free is “low information voter,” a reference to citizens who don’t want to or don’t have the time to pay attention to current events and the actions of their leaders. Their votes are based on a nebulous reaction to the general mood established by the campaign and coworkers. In many examples in my book an overline is used to explain what the joke stems from or what situation is referred to. This device used to be thought of as a crutch, but with low-information voters it has become a necessity.

The attempts at playwriting by cartoonists, even if only as helpful exercises, have other parallels. Some plays are more effective on a bare stage. Some benefit from complicated and richly detailed sets. In some plays there is a combination of hell breaking loose and unexplainable farce. Some plays depend on visual humor, some depend on vast amounts of talk. Sometimes there’s too much talk. In drama there is a rule that if a gun shows up in the first act, it better go off by the third act. All of these considerations can instruct cartoonists. The great British cartoonist Carl Giles, who is cited in this book a number of times, created the ongoing comic drama of a London family and their immediate environs. The political commentary was delivered over the breakfast table, in the pub, or on holidays. Giles’ work presaged all the situation comedies that followed, and his series ran daily for nearly fifty years.

What Will Happen to Paper?

People whose opinions have not been formally requested predict that paper newspapers will disappear. So will paper books. Electronic means are cheaper, faster, and more attractive to younger readers who will come to regard the news as simply an extension of digital games. These predictions are of course not true. In business, paper use has increased even as newer and faster forms of electronic media have burgeoned. More newspapers are being published in the world than ever before. The predictions that radio would replace newspapers, that television would replace radio, and that the Web would replace television are alike in their shortsightedness. In the final analysis people will want what they find interesting, amusing, and necessary, regardless of how it is delivered. That desperately old-fashioned form of entertainment, live theatre, with live actors and live musicians performing before a live audience in the same way they did back in early Athens, is as popular as it ever was, and getting ever more money for tickets.

The earliest political drawings were on cave walls. A dinosaur was rendered in the newly discovered charcoal and, then while no one was watching, quickly labeled “the deficit.” So we can assume that having survived this long, cartoons will not be counted out. The transfer to digital forms has begun and is successful. Some cartoonists have mastered just enough digital animation to make it seem worth the effort, but for others a nonmoving drawing, presented in fearsome silence, is even more effective. Things may speed up, as they have since the invention of the wheel, and the timing of comedy may be compressed. We will know more about ourselves as social animals, and know far more about how to solve the daily problems. Our interest in politics and economics will grow and be more resistant to falsehood. Things will seem much more serious, and, at the same rate, the need for a humorous angle will increase.

A lesson can be gained in the realization that, whatever the form or medium, the basic drawing is still the heart of the message. A cartoon, whether or not it moves, or is rendered in “millions of colors,” or has voices and noises, still relies on the basic skills of graphic art: the practiced eye, good writing, and a lashing of informed wit. The computers may move information faster and deliver the answers faster, but people still move at the speed of life, not light.

Advice to the Young Cartoonist

Political cartooning isn’t lucrative, but it is fun, and in its own way staves off ill temper and madness. It is inside work and requires no lifting. Some feel it is necessary to have at least one cat in attendance. Cats display a merciless self-interest and nanospan of concentration, in which characteristics they resemble the average readers, at least those under thirty. They can also be used as models, since a cartoon suffering from weakness of humor and wit can be improved a little if there is a cat wandering around in the background. No one knows why this is so.

As a milieu and profession, cartooning is something that will award you a presumed expertise in politics and some small bit of attention at dinner parties, just shortly before the subject returns to real estate. The work is sedentary, not very healthy, but accompanied with diet and exercise, won’t make your physical condition any worse. Many political cartoonists have gone on to happy senescence. Some have even been lucky with ambitious but nonobservant starlets who themselves have been rejected by screenwriters.

Other bits of advice are the usual about not quitting the day job and about slow, steady self-improvement. Limited expectations are always advisable, as is a distrust of early success. Cartooning is an art form, and, like any of the forms of art, the key to success with it is longevity. To alter that famous philosopher, Mr. Spock, live long and you might prosper.

This essay is excerpted from the introduction to Jeff Danziger's book, The Conscience of a Cartoonist: Instructions, Observations, Criticisms, Enthusiasms. It is available now. Thank to James Sturm and the Center for Cartoon Studies for facilitating this publication.