Like good character actors, some artists are everywhere and nowhere, consistently putting out high quality work but not drawing particular attention to themselves. A Canadian artist who lives in New York, Leanne Shapton is one of the more interesting artists working in the U.S. right now, and though you may well have seen her stuff—if you watched Spike Jonze’s exercise in awkwardness, Her, for instance, you’ve seen the artist’s rendering of what two people having armpit sex might look like—you may not yet know her name.

For an artist her age—Shapton is 41—she has already had a large and tremendously varied output. She paints lettering and patterns for book covers by Harper, New Directions, and Vintage Classics, and runs J&L Books, a small art book press, with the photographer Jason Fulford. She has seven books to her credit, some of which are almost purely visual and contain little or no text, while others (well, one, anyway) is a good old-fashioned prose piece with a few paintings thrown in.

Though she’s not really a comics artist herself, Shapton has also had a hand in putting the work of many cartoonists in front of a mainstream audience. As the art director of the Op Ed page at the New York Times from 2008-2009—and before that, for the Avenue section of Canada’s National Post—she hired visual artists with from a variety of backgrounds, from Blexbolex to Jillian Tamaki.

“I loved that they could think in terms of image and narrative, that they could make things personal, and that they could write,” Shapton said in an interview I conducted with her over email, which took place over the course of several weeks.

“I wanted to have as much cross-pollination between text and image as possible.”

She also hired fine artists like Yoko Ono, Ed Ruscha, Christina Marclay, Michael Landy, Collier Schorr, and “writers who could design,” including Dave Eggers.

Most of all, she loved working with graphic designers, “people who worked closely with text and books and could think about how a visual piece will read.” (One of her Op-Ed page artists was Peter Mendelsund, whose recent book What We See When We Read? is a textual-graphic meditation on that very idea.)

“I've never really felt at home in the illustration world or design worlds,” Shapton said. “I've always felt most at home in the book world and graphic novel world, though I've only ‘written’ one traditional book (and arguably at that).”

To be sure, her own work hovers somewhere between fine art and decorative design, literary in a classic sense and experimental in a number of playful ways. Two of her books, The Native Trees of Canada and Sunday Night Movies, were published by Drawn & Quarterly’s Petit Livres imprint, which features titles that are a little artier than straight-up comics. Also on the imprint is Lady Pep, an anthology of illustrations and collages from the “post-comic career” of the never-boring Julie Doucet.

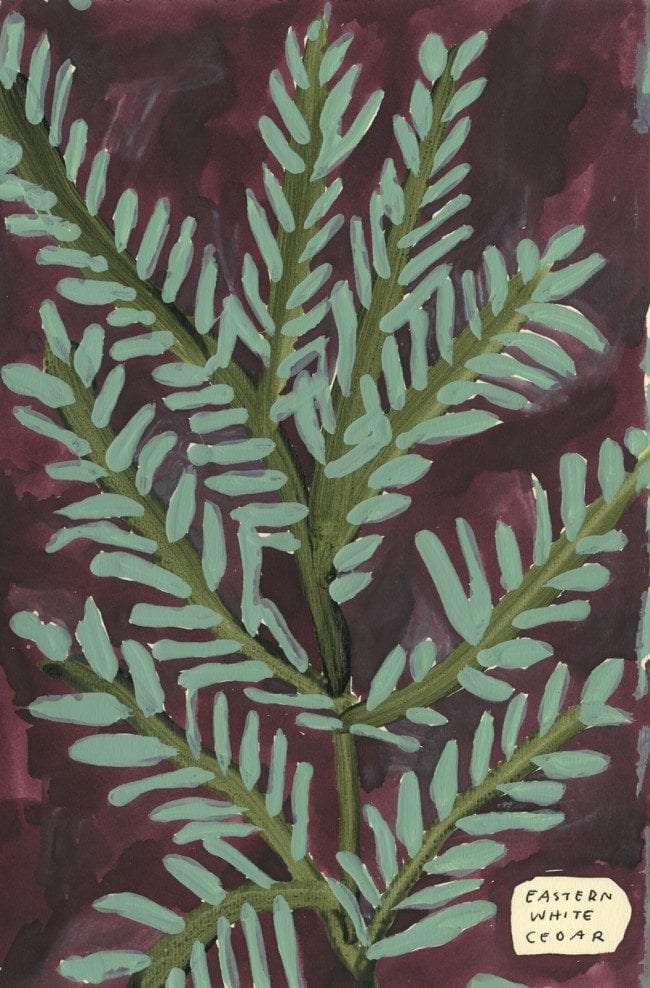

For Native Trees, Petit Livres’ best-selling book to date, Shapton took inspiration from an antique Canadian government-issued reference pamphlet that she found in a Toronto bookstore. In a short essay Shapton published in The Paris Review, she wrote that her love of trees is tied to her Canadian identity, and that she began painting her interpretations of the leaves in an effort to explain this sweet form of patriotism to her English boyfriend (who’s now her husband).

The reference book showed the leaves in stark black and white drawings, placed on a grid for scale. For her version, Shapton used house paint, Dr. Ph. Martin's concentrated watercolors, and fountain pen ink in rich colors from a slightly less (or more) than natural palette. Some of them appear to have been applied thickly to the page, a bit like a kid going outside the lines of a paint-by-number. The resulting images are near-abstractions, more decorative than botanical, as though the leaves have been considered for their potential as wallpaper designs—though one Amazon reviewer reckons the book would be a useful guide on a “leaf walk,” and upon reflection I think I agree. When you’re trying to identify a tree or other plant, all you need—or, often, all you have—is a broad impression of shape and color, a hazy and composite memory of all the leaf drawings and actual leaves you’ve seen before. It’s fair to say that that is what these are: Pictures of Shapton’s recollections of the leaves, rather than the leaves themselves.

The book Shapton considers her most “traditional” is Swimming Studies, a memoir about her past life as a teenage competitive swimmer at the near-Olympic level. Striving to make the Olympic team can be seen as a kind of ultimate patriotism, of course, but Shapton takes us to more subtle places, too, poking gently at the topic of her own background by showing us tiny domestic scenes, like her Filipino mother’s efforts at friendliness with the standoffish white ladies at the donut shop.

Unsurprisingly, though, much of the book deals with ideas about the body. The body in motion, the animal responses of hunger, pleasure, fatigue. Shapton isn’t entirely sure she understands why swimming mattered to her, or why she eventually stopped doing it, so she investigates her physical self to try to make sense of it all. We learn what she ate and how it made her feel. We watch as she leaves her mother’s car at five a.m. on a frigid Canadian morning and enters the foggy hothouse of the indoor pool. We are touched and sympathetic as she forms brief, intense crushes on strangers and feels moved to impress them. In her prose, even more than in her paintings, she’s always peering through the murky waters of her own desire.

But her awareness of the world from an artist’s point of view is evident even here. At one point she looks up a former coach and sits in on a practice with him, some 20 years after she quit swimming competitively. She watches him work, and sees that: “His expressions jolt me back into the firm macro grip on time I had as a swimmer. The ability to make still lifes out of tenths of seconds.” Shapton’s language, in this book and in others, is like a series of still-lifes, too. Reading Swimming Studies—which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Autobiography—we have a strong sense of her as an observer, more a documentarian than a memoirist, even in the realm of intense athletics where she is unarguably a doer.

And though the book scarcely touches on anything she did during her teens and twenties that wasn’t swimming, at one point she flips over and kicks off into another direction like an expert racer, and boom! She’s talking about art. The dogged discipline she learned as in training applies to her practice of drawing too, she writes, explaining it this way:

“Whenever I begin a large project, and when, as a swimmer, I contemplate a practice, a mental image appears: a grayish Sisyphean mount I need to ignore in order to begin to climb. After twenty years [away from swimming] I still search for the dumb focus I had as a competitive swimmer. After a hundred workouts I might be faster. ... After a hundred lengths I might be healthier. After a hundred pages, a hundred sketchbooks, when will it feel right?”

During the first few years after she failed to make the Olympic team and began to drift away from swimming competitively, Shapton enrolled at McGill, where she studied art and was fascinated by the daguerrotypes she saw in a history of photography class. She describes the experience: “A hundred ghost stories, in black-and-white, flash up one by one out of the dark.” Elsewhere in the book are a batch of painted portraits of her teammates, one to a page, and each is made up of just a few swipes of white and grey paint on a black background. They look both complete and elusive, as if they’ve just floated to the surface of our ability to see them; they look like ghosts.

While she was still in college, Shapton self-published a book of drawings with her friend, the designer and photographer Jason Fulford. She’d been feeling homesick for Toronto and she made pictures of her hometown that led to the creation of a small collection (Toronto).

“Jason and I loved books and just wanted to start making them ourselves,” she explained in an email. “He had already made his first, Sunbird, and learned the ropes of printing and going on press. I was art-directing a weekly magazine at the time I made Toronto, so I knew about production schedules and design.”

The two friends went on to produce other books, and in 2004 they incorporated their efforts as the non-profit J&L Books, which has published titles by photographers Gus Powell, Michael Schemlling and Ted Fair, and “a book of people dancing” called Dancing Pictures, among others.

In 2003 Shapton got her green card—a process that had taken a few years—and right away moved to New York, arriving in the city without a job. She found one at Condé Nast, creating the prototype of an art magazine that never materialized. But by then she was working on her first book, Was She Pretty?, which she sold to Sarah Crichton Books, and five years after moving to the city she was hired by the New York Times. Her career has grown upward and outward ever since.

Was She Pretty? is a collection of pieces that speculate fretfully about the ex-girlfriends of current lovers. It consists entirely of simple black pen-and-ink portraits of the women with short descriptions of them on the opposite page, resulting in tiny but oddly evocative studies, each containing the kinds of mundane details that make a person, well, them. Some of the biographies seem meant to impress us with lists of professional accomplishments, while others just tell an idiosyncratic detail or two. Most are delivered with droll restraint (“Sheldon’s ex-girlfriend was Dianna. She was uninhibited.”), but others are worse at hiding their green-eyed monster (“Lionel’s ex-girlfriend Edie enjoyed Brahms. But she preferred money.”). Most of the exes are women, but sometimes we get a tidbit about that ex’s ex (usually but not always a dude), and we momentarily have a dizzying sense that everyone in the world is ultimately connected in this way, like those unsettling STD public service ads that went something like, “When you sleep with someone, you’re sleeping with everyone they’ve ever slept with.” Yikes.

Was She Pretty? is about jealousy, of course, but what makes it interesting—what makes it Shapton—is that it explores more than the mean feelings we associate with envy. In fact, most of the portraits are decidedly not mean, not very emotional at all. Instead it focuses on the intense curiosity that jealousy can invoke. Each description is a sad little answer to that old question, only ever uttered aloud as a joke, What does she have that I don’t?

“Bjorn admitted to having “spicy” sex with his ex-girlfriend Yael.”

“Ken’s ex-girlfriend Sonya had been wearing Japanese designer clothes for decade.”

“Jacob’s parents adored his ex-girlfriend Cynthia.”

The book’s inside cover informs us that it could share the shelf with William Steig’s “psychologically revealing early work,” and I could see that. Shapton names him as an important influence because, she says, “I loved how he had a light, yet knowing and adult touch on topics like mental illness (The Lonely Ones,) or child abuse (Agony in the Kindergarten,) and how simple his writing was.” What the line drawings put me to mind of, though, are the sad, droll little doodles that British poet Stevie Smith sometimes made to accompany her poems, in part because the short descriptions that sit opposite each of Shapton’s drawings are like poems themselves.

*****

Last month saw the publication of an anthology, Women in Clothes, on Blue Rider Press. A great big brick of a book that Shapton compiled with friends Sheila Heti and Heidi Julavits, Women in Clothes is absolutely packed with content—just over 500 pages’ worth. Unlike most themed anthologies, the contributions aren’t all essays or comics, but an eclectic range of media and formats. Also unique is the massive contributor list—as Heti puts it on her website, the book includes the “voices” of 639 women—and it includes famous ladies and regular folks alike, the latter having participated in so-called surveys that are styled like questions you’d ask a close friend. (“What’s the situation with your hair?” is one.) The responses are so varied, humorous, and brief as to result in a kind of massive-scale cocktail hour; appearances by Tavi Gevinson, Miranda July and elder hipsters Kim Gordon and Cindy Sherman, give the book a cool, but not stand-offish, attitude.

Of the title’s unusual phraseology, Shapton explains: “It came from a desire to have a very simple D.H. Lawrence-sounding title—Sons and Lovers, or Women in Love—and we quickly came to Women in Clothes. I like that it implies there is a women inside her clothes and we do indeed talk more about the interior than the exterior.”

Several visual pieces are included, though Shapton’s paintings only make one appearance, as the pattern adorning the book’s cover. She explains that all three editors commissioned the pieces, often working together on a single project.

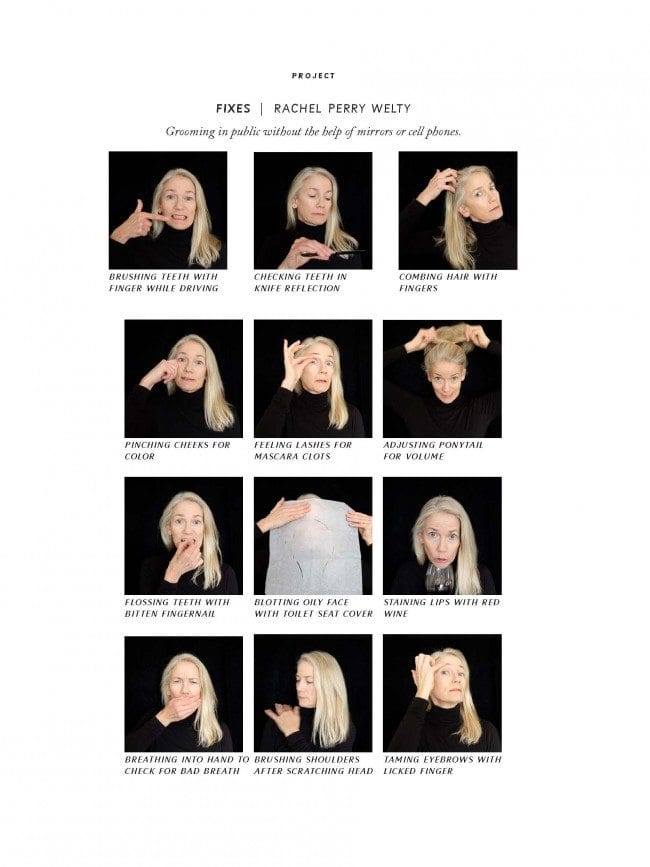

“‘Fixes” came out of us all asking friends what they did to groom in public,” Shapton said of a piece by the performance artist Rachel Perry Welty, in which she acts out tics such as “checking teeth in reflection on a knife,” “adjusting ponytail for volume,” and “flossing teeth with a bitten fingernail.” The editors pondered the (occasionally disgusting) lists of behaviors their friends provided and tried to think about how to present them, when Shapton remembered she’d met Welty at an exhibition and asked her to perform them.

One of the strongest pieces in the book, “Ring Cycle”—which is uncredited in the book by accident, but was made by Shapton—is a collection of interviews with women in a newspaper office about the rings they’re wearing, accompanied by photocopies of their hands. This piece, like many others in the book, has a wonderful way of feeling carefully considered and off-the-cuff at the same time—like your favorite outfit, perhaps, which makes you look great but also like you haven’t tried too hard.

“I was trying to think of a way to cover jewelry and I love the way photocopies look. (I wanted the entire book to have a lo-fi / art project feel to it, plus we had no money for shoots),” Shapton said. “I wanted to ask women who work in an office and have day jobs, and whenever I was at the New York Times I would ask a handful of women if I could interview them about their rings. It was very simple and straightforward. I didn't need to explain much. People like to talk about their life, and jewelry, because it is so personal, is a way in.”

Reading the book, I thought about some of the other intelligent writing I’ve read about fashion lately, like Linda Grant’s brilliant essay collection The Thoughtful Dresser; WORN Magazine’s feminist take on the topic; and It’s So You, a fairly queer anthology of essays about clothing edited by Michelle Tea and put out by Seal Press. Could it be that there’s room for women—“serious” artists and regular people alike—to talk about clothing and not be laughed out of the room?

“I don't think there is a stigma about it anymore,” Shapton said when I broached the topic. “Clothing is culture and the more it is examined, the more curiosity grows and as a result there is more demand by discerning readers for intelligent writing on the subject.” She adds: “You specify women but men are writing about clothing, too. I was blown away by a piece Buzz Bissinger wrote (in GQ I think) about his dressing habits.” (Yep, it was GQ, and “dressing habits” is the politest possible way of describing what the essay was about. Read it if you haven’t, and prepare to have your mind blown.)

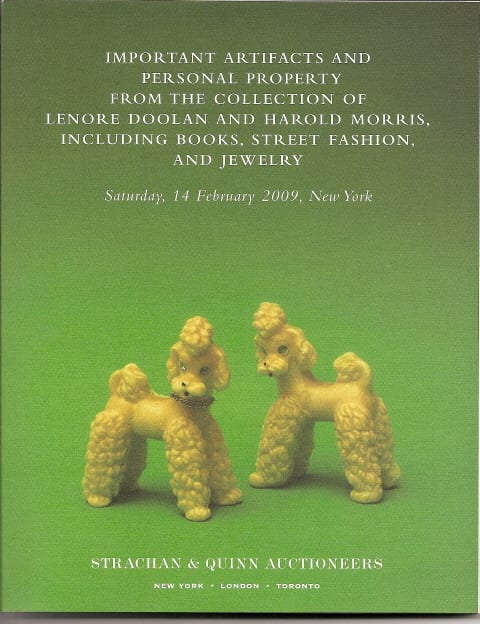

Shapton, for her part, has already explored her interest in the meaning of clothing and culture in another book, Important Artifacts and Personal Property From the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry. Published in 2009, Shapton’s second book is, for my money, still her most exciting one. Styled like an art auction catalog with only photos of objects and their captions to tell the story, it chronicles the lifespan of a romantic relationship, from its giddy beginnings to its drawn-out, not-with-a-bang-but-with-a-whimper end.

Doolan and Morris, referred to by their last names throughout the book, are pretty high fliers: She’s just gotten a food column for the New York Times, and he’s a photographer who’s always sending her plane tickets to join him on a shoot in London, a month in Peru, a sailing trip down the Bosporus. But the book is elevated above mere social commentary; to Shapton’s credit, it is about people, not types. Though we can get a sense of the sort of person someone is by looking at the magazines they read (Cook’s Illustrated, Lot 1175) and the hats they wear (vintage Yves Saint Laurent, Lot 1151), what Shapton is interested in, really, is these two individuals, and what the things they bought and owned and gave each other can tell us about them.

Doolan makes yarn pompoms for the Christmas tree and uses that really expensive Creme de la Mer moisturizer; Morris is a letter-writer who saves fortune cookie fortunes. Doolan looks sort of wan and wispy with her natural-blonde bob and slender build—she’s played, in the snapshots being offered on auction, by Sheila Heti, a personal friend of Shapton’s—but we know from Morris’ letters to her that underneath her mild looks lies a violent temper. (“When you raise your voice and throw things, I shut down and go cold,” Morris writes in “A handwritten note,” Lot 1247.)

Some of the things you need to understand about these people reveal themselves more slowly, though. Lenore (it feels weird to call her by her last name, even though the book does) leaves notes to herself in various places, in the margins of books and on computer print-outs. Some of these I skimmed over and mistook for grocery lists until it dawned on me that they were actually spooky little notations of her daily food intake, a habit that seemed to pick up during stressful times with her boyfriend. On page 105 of a paperback copy of Wuthering Heights she’s written:

iced coffee

apple

iced coffee

green tea

hamburger w/out bun

vodka tonic

—an eating-disordered list, if there ever was one. In the same book, a hundred pages or so later, she jots down the name of a friend’s shrink.

Like all of us nowadays, Shapton is a connoisseur of material culture. She knows what a person’s taste in clothing, movies, and bistros means. At the same time, she doesn’t know what any of these things mean, because it’s impossible to. Her portraits of these two people are tantalizing, maddening composites that are never quite made whole. We can try to fit together the pieces but even when they go together, we’re left with unanswered questions. Namely, why did the couple split up? We have no trouble feeling how it happened—we’ve all been there—but we’d be hard-pressed to explain what exactly went wrong, and why it is that loving someone isn’t always enough, on its own, to make it possible to have that person in your life. Shapton gets this, and so instead of explanations she gives us figurines instead, and receipts from restaurants, and hammam towels from Turkey. Because what else can you do?

Important Artifacts has recently been optioned to be made into a film, and though the project may never come to fruition, early talks have named Brad Pitt and Natalie Portman for the title characters. What does this mean for Shapton as the author of the original work?

“I think it means different things for different writers, but in this case I decided not to be involved in the screenwriting. I wanted another writer to interpret the book however they wanted, and was excited by that idea,” she says.

“But on the other hand, I would not feel the same if Swimming Studies were ever optioned. With Important Artifacts I felt I'd found the best expression of my idea. But with Swimming Studies, I have ideas about how a translation to motion picture could work, and not at all be faithful to the book, but become another piece of art. I think it all depends on how much is still in the tank and how much the material invites and involves you.”

***

While poking around the internet to see more examples of Shapton’s work, I saw that she’d done the lettering for the cover of Diary by Chuck Palahniuk, a writer I have both loved and hated. I found myself wondering whether it matters to Shapton’s process whether or not she liked the book she’s interpreting-slash-decorating.

“I prefer to work on books I really love,” she said. “It helps me find more idiosyncratic or personal connections and symbols, and helps engage my intuition. I'll try to think of the book I want to hold in my hands, that represents what the story feels like to me. The process is long and never the same, often requiring about 25 sketches.

“And sometimes I have to just take work because it is work.”

If every one of Shapton’s projects is different from the last, the most different are probably her charming wooden books, objets d’art that speak volumes (har) about the idea of the book as an object.

“They began as part of a J&L Books art show where we painted wooden versions of the books the artists we published loved,” Shapton explained. “As art and photography publishers, we’ve always been interested in the fiction and non-fiction books the people we work with read and cite as influences. After the show, I started making them when J&L Books would go to art book fairs.”

At the time, she said, she was totally broke and couldn’t get any steady work, so she was grateful when John Derian Company, a shop in the East Village, began carrying them. She made between 150 and 200 books for the store, cutting and sanding down wooden blocks that she then primed and painted with original designs. But when she was hired at the Times, her wooden-book output took a hit.

“For all of their simplicity, it’s time-consuming work,” she said. “I think people are attracted to them because they are little tributes to books, and the poetry of the isolated titles is affecting. And you're right, the book is beginning to be seen as a bit of a fetish object. But I'd take a first edition over a wooden book any day.”