The French artist Annie Goetzinger, who died on December 20 at the age of 66, could never remember a time when she wasn't drawing. "The moment I could talk, I asked for paper and a pencil and whatever I drew was a story with a theme."

As soon as she learned to read, Goetzinger devoured comics. She loved the illustrés of the 1950s and 1960s, then becoming known as bandes dessinées. But it never occurred to the young Annie that she could create one. Even at the magazines which were aimed at little girls – the likes of La Semaine de Suzette, Lisette, and Ames vaillantes – making Francophone comics and cartoons was a male domain.

Nevertheless, 2017 marked Goetzinger's forty-fifth year in the profession. Last March, she published Les Apprentissages de Colette, a snapshot of the famous author's difficult and decisive youth. Like her 2013 album about Christian Dior (Jeune fille en Dior, published in English in 2015 as The Girl in Dior) or her 2011 fantasy Marie Antoinette, la reine fantôme (Marie Antoinette, Phantom Queen, 2016), it will appear in English this summer.

Goetzinger's path was less tortuous than those of her heroines, but she too made history. As she told the women who organized the anti-sexist comics collective to which she belonged, "Over time, I've pretty much seen and heard it all." Tributes to her, including those by the collective (BD Egalité, Female Comics Creators Against Sexism), have united to acknowledge Goetzinger's role as a "grande dame of the bande dessinée."

But, as friends and fellow pioneers like Florence Cestac have asked, why were these accolades withheld until her death? Why consecrate her achievements only after she is gone? Their anger recalls the moment, exactly two years ago, when Angoulême's International Comics Festival put forward thirty men – and not one woman – for its prestigious Grand Prize.

Female artists of every age reacted with fury. But the catastrophe exposed something central: just how much BD history is still buried. The famous "golden age" of Franco-Belgian comics was an all-male epoch and one that started to change only during the 1970s. That shift was due to a small group of innovators, women such as Claire Brétecher, Chantal Montellier, Jeanne Puchol, Nicole Claveloux, … and Annie Goetzinger.

Women had never been totally absent from Francophone comics. But, over decades, their role in the industry mirrored the place they held in society. So they worked as men's colourists, secretaries and assistants.

Bécassine, often considered comics' first female protagonist, was conceived – but not drawn – by a female editor. She was Jeanne-Joséphine Spallarossa, known to her readers as "Jacqueline Rivière." But what was true for Spallarossa went for every one of her sex: their editorial work was limited to the juvenile press.

In this realm, the publications for adolescent males (Le Journal of Tintin, Spirou, Coeurs vaillants, etc) launched careers like those of Hergé, Jijé, and Franquin. But for a creative female, there was nothing similar. All the magazines where women worked had an inflexible brief: they were supposed to educate supportive, obedient wives. During the decade Goetzinger turned twenty, all that changed.

The artist was born in Paris' 20th arrondisement, historically a bastion of the working class. "I come from a family of woodworkers and dressmakers," she told the eminent BD historian Gilles Ratier. "They were all artisans, people who loved their work, who started out with nothing and made it into something… But they were also people who loved books and cared about culture." One of her great aunts made haute couture at Maison Lanvin and most of Annie's clothes were designed and sewn by her grandmother.

Goetzinger intended to follow in their footsteps. She won a place in textile studies at L'École Duperré, then known as the L'École Supérieure des arts appliqués. A product of the movement to emancipate women, the school was focused on creative job training. In 1970, it merged with a pair of institutions for men and it has produced bédéistes such as Killoffer, David B, Sylvain Chomet (The Triplets of Belleville), Julie Wauters of the Troglodyte collective, Juliette Mancini, and Elsa Abderhamani.

When Goetzinger arrived in 1967, not a single class she took was mixed. But the school's curriculum, which she later called "rather progressive" required a study of the bande dessinée. This course was run by Georges Pichard – an auteur known primarily for his erotic comics.

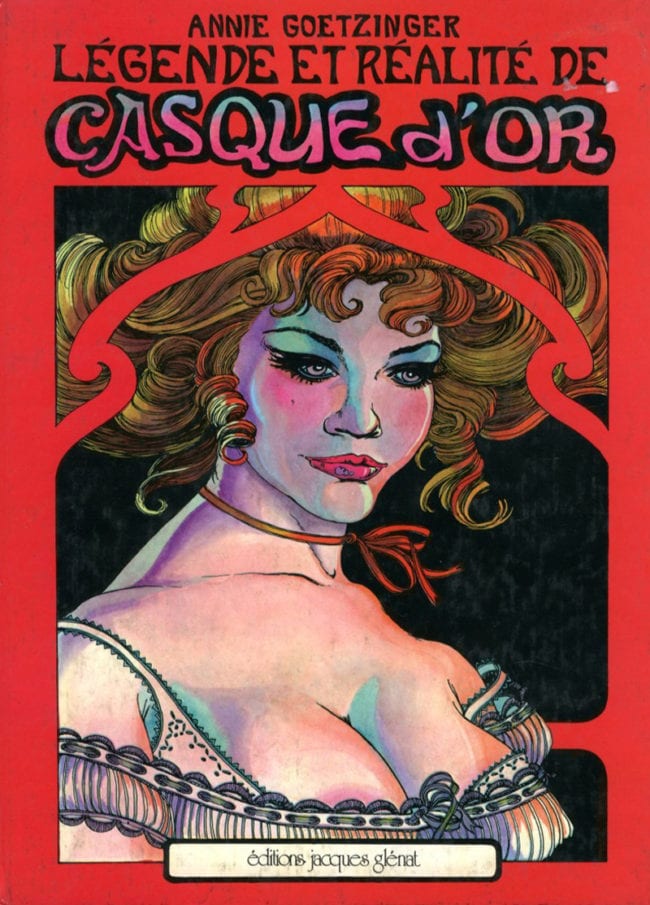

Pichard had each of his students create an actual comic and Goetzinger decided to tell the story of Amélie Élie. Élie, a prostitute of the Belle Époque, had been a colourful legend in the student's quartier. Known as Casque d'Or – "Goldilocks" – for her shining hair, Élie was at the heart of a war between two gangs. In 1952, Jacques Becker made a movie about her. But, as a student, Goetzinger had never seen it.

Two artists featured in that jury which evaluated her pages. One was scriptwriter Jacques Lob, who later created Superdupont for Gotlib. The other was Fred (Frédéric Aristidès), author of a popular strip called Philémon. Fifteen years later, Lob would receive Angouleme's Grand Prize. But, within a year, he was asking Goetzinger to draw his work.

Goetzinger always credited Pichard's class with changing her life. "As a form, the bande dessinée spoke to me straightaway. It was a way of telling stories I found extremely moving."

By 1972, however, she was a penniless graduate – so Goetzinger rented a room and started to pound the pavements. (Because her landlady turned out to be a militant feminist, drawing political posters brought her a break on the rent.) Then a female editor at Lisette accepted her comic "Fleur" and, through Lob, she found work at Pilote.

Four years after Goetzinger left school, Légende et realité de Casque d’Or was serialized; in 1976, it appeared as an album. The Angoulême Festival named the artist its Meilleur Espoir ("Best Hope") and voted Casque d'Or the "Best French Realist Work." That award is now the Fauve d'Or or year's Best Album.

To modern eyes, a flip through Casque d'Or comes as a shock. It is filled with the era's garish colors and love of Art Nouveau, and the louche carnality of its characters feels more earnest than earthy. The editor who commissioned it, Henri Filippini, describes it as "an album of apprenticeship." But, as he also notes, everything that made its author's long career is already present. Casque d'Or demonstrates Goetzinger's love of setting scenes, her taste for historic dress and décor and her insistence on a female point of view.

The author followed Élie's story with Aurore, a life of the cross-dressing novelist George Sand (1804-1876). With a text by the writer Adela Turin, the album won First Prize at the Bologna Book Fair. This was the world's most important market for children's literature but the project had not been a happy one. "I did it for L'Edition des femmes," Goetzinger told Gilles Ratier, "who were a women's publishing house. But they turned out to be one of the worst publishers I ever encountered. Not only did they lack any humor or perspective, all of them were totally preoccupied by 'the message.' So I had no freedom… and I got no author's rights."

From then on, when it came to collaboration, Goetzinger trusted her instincts. This brought her a life whose creative partnerships endured for decades. Having entered a world where men held the power, dominated the visions and usually reaped the big rewards, she proved herself not just an equal but a highly creative partner. The addition of her frankly female point-of-view, plus Goetzinger's interest in rigorous research, often brought stories a different reach and depth.

Teamwork was integral to Goetzinger's universe. Her first important collaborator was Spanish author Victor Mora, who she met in the office at Pilote. With Mora, she created the exploits of Felina, the cat-suited offspring of a Spanish anarchist and a nun. Their three-volume fantasy follows this vigilante as she tracks the mysterious figure who ordered her husband's death. It was Goetzinger's first popular success.

The next decade brought her a second crucial colleague. This was Pierre Christin, already the co-author of a bestseller, Valerian. That series of space stories, which influenced Star Wars, had introduced Laureline – one of French comics' first adult females. Laureline's only real predecessors are Barbarella (1962; 1964) and Guy Peellaert's erotic, doll-like Jodelle (1967).

Christin and Goetzinger would break new ground of their own, starting in 1980 with La Demoiselle de la Legion d'Honneur. This story begins when its protagonist's parents are killed in French Indochina. Young Aline Erckmann is then sent back to France, to be housed and schooled in a Maison de la Legion d'Honneur.

Such maisons are actual government homes for veterans' children, established in 1805 by Napoleon. After their repressive schooling, Aline's trajectory depends upon the men she meets. She marries a captain whose far-right views take her couple to Africa, where he is working as a mercenary. Here, Aline becomes a witness to female circumcision, takes a lover, loses him and then loses her spouse. Still conservative but also restless and bored, she travels with another paramour to Cuba, Argentina and, finally, to the America which is at war with Vietnam. There an epiphany sends her back to late-'60s France, keen to save her son from the bourgeois life she once embraced.

The book's publication caused a genuine scandal. At the time, the Legion d'Honneur and its very real maisons was headed by the late Charles de Gaulle's son-in-law. Goetzinger received an in-person rebuke and publisher Georges Dargaud almost lost his own Legion d'Honneur. But the rebellious authors remained unrepentant and, for over three decades, they explored similar stories.

BDzoom and Gilles Ratier

The year after La Demoiselle they published La Diva et le Kriegspiel, which dramatizes collaboration with the Nazis. In 1985, their La Voyageuse de la petite ceinture followed Naima, an immigrant fleeing the marriage arranged by her family. They went on to look at things like the life of working girls in fashion (Charlotte and Nancy, 1987), the debits of modern communication (Le message du simple, 1994) and the legacy of British colonialism (The White Sultana, 1996).

Christin and Goetzinger also created the series L'Agence Hardy, a 1950s-set retro romp that stars a girl detective. Their 1989 Le Tango de disparu, about disappearances under Argentina's junta, is seen as one of the first graphic novels.

From Casque d'Or to Jeune fille en Dior, Goetzinger continued to script scenarios of her own. She also wrote and drew erotic tales, the first of which appeared in 1974 in Le Canard sauvage. Some of these – also published in L'Echo des Savannes and les Humanoïdes Associés' Fripon series – have scripts by Rodolphe Jacquette, Serge Le Tendre, or Jacques Lob's wife, Couetsch Bousset. But Cinéma du quartier ("Neighborhood Moviehouse"), Ruban bleu ("Blue Ribbon") and Le Lingère amoureuse ("The Smitten Chambermaid") were each written and drawn by Goetzinger. Via the anthology Eros Gone Wild, several such works have appeared in English.

Ratier

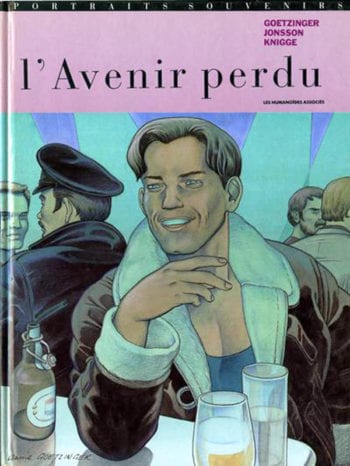

In 1992, Goetzinger was approached by the German writer Andreas Knigge and a Norwegian poet, Jón Sveinbjørn Jónsson, to create a story called L'Avenir perdu (The Lost Future). Except for one comic – Jo, created the year before by Dérib – this was the first BD to deal with AIDS from a gay perspective. Even today, it is considered among the best.

Despite her colossal output, Goetzinger's work was not confined to comics. She also illustrated books, designed for the theatre and drew for the daily press. From 1999 until a fortnight before she died, she supplied the images for a weekly column in the paper La Croix.

That column is written by Bruno Frappat, formerly a supervising editor at Le Monde. It was Frappat who, in 1985, published a famous manifesto entitled Navrant ("Shameful"). In it, four leading dessinatrices – Chantal Montellier, Jeanne Puchol, Florence Cestac, and Nicole Claveloux – denounced the misogyny of the comics around them. Despite progress having been made in the 1970s, they felt graphic humor had once again become "macho," "pornographic," and "infantile."

Goetzinger was not among the signatories. But she always acknowledged a female artist's world was harder. "This has never been an easy job to practice – never. You have to have tenacity and nothing is ever guaranteed. Success or not, the next album is always there in front of you." During the controversy of 2016, Le Monde called to ask her: Was there really such a thing as "the female bande dessinée?"

Of course there was, Goetzinger replied, and what about it? What was wrong in acknowledging – or privileging – female perceptions?

The role of the grandes dames like Goetzinger is enormous. But some of their contributions are more easily seen than others. Claire Brétecher made her era into a comedy of manners: a fresh genre that is graphically droll and linguistically brilliant. Florence Cestac worked to change not only comic perspectives but how bandes dessinées are published. Chantal Montellier's views about storytelling were and remain an expression of her radical politics – and, with the annual Prix Artemisia, she has ensured they will be remembered.

Goetzinger's legacy might appear more minimal. Little of her work ever made it into English and much of it is effectively out of print. Many of the moments it was addressing are forgotten. So is the fact that, as one critic wrote, "When Annie Goetzinger started out, many readers were shocked that a man and woman could even make a comic together."

In fact, her work was critical. Goetzinger's lasting importance resides not in her style or politics – it derives from her very existence and example. When there was only a handful of women to watch, she showed what could come of painstaking research and careful choices. For her, the key to retrieving any past was always a person, an individual with a specific imagination. She helped win us access to worlds as different as those of Chloe Cruchaudet's Mauvais Genre (2013), Agnes Maupré's Chevalier d'Eon (2014), Penelope Bagieu's California Dreamin' (2015), Virginie Augustin and Hubert's Monsieur Désire? (2016), and Isadora by Julie Birmant and Clément Oubrerie (2017).

If Goetzinger favoured stories about women, they include not just the powerful but also the passive. She depicted fewer heroines and "role models" than she did individual, ordinary females. Her work depicts public servants and prostitutes, performers and militants, envious workmates and wartime traitors. While some of these are victims of their circumstances, others our defeated by their own self-regard. Goetzinger also gave us characters like Aline – unequipped to analyze those lives they are living.

Annie Goetzinger's great accomplishment was simply that she worked, worked with an unfailing skill and curiosity. She made comics her job – just as men had done, without a thought, for decades. In 2014 she told Gilles Ratier, "I love the past because of certain events in my life. But I never wallow in it; I avoid nostalgia. Having said that, if I'm stuck in the pigeonhole of 'comics history,' I'll be fine with that. After all, it's a warm and cozy spot."

courtesy BDzoom and Gilles Ratier

With special thanks to Gilles Ratier and BDzoom.com.

• Annie Goetzinger's The Girl in Dior and her Marie Antoinette, Phantom Queen are available in English from NBM, which will also publish Provocative Colette. An English version of Goetzinger and Christin's The White Sultana is also available from Europe Comics. Chloe Cruchaudet's Mauvais Genre is available in English as Deserter's Masquerade.

• The winner of this year's Prix Artemisia for this year's best BD by a female auteur will be announced on January 9, 2018