Joe Infurnari has some battle scars to show for his years in the comics industry, and he's not afraid to tell the stories behind them. The Toronto-based artist and occasional writer recently completed "So What That You Can Draw!?", a collection of his sketchbook art inspired by a massive falling-out with a longtime artist friend. Cribbing its title from a poorly-worded email Infurnari received from that friend, Infurnari uses the incident – and his own mostly unrelated sketches – to meditate on both the larger concept of empathy and to consider his own role in the disagreement. The final line of the book is "I'm sorry."

Joe Infurnari has some battle scars to show for his years in the comics industry, and he's not afraid to tell the stories behind them. The Toronto-based artist and occasional writer recently completed "So What That You Can Draw!?", a collection of his sketchbook art inspired by a massive falling-out with a longtime artist friend. Cribbing its title from a poorly-worded email Infurnari received from that friend, Infurnari uses the incident – and his own mostly unrelated sketches – to meditate on both the larger concept of empathy and to consider his own role in the disagreement. The final line of the book is "I'm sorry."

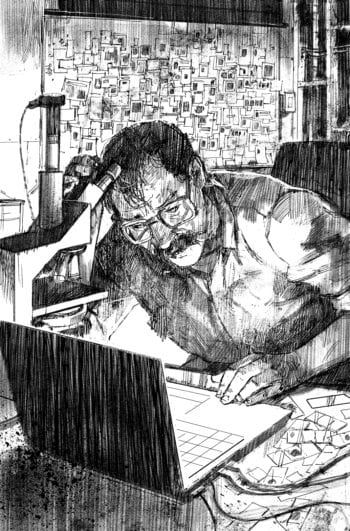

Infurnari applies that same self-awareness (and often self-deprecation) to numerous other skirmishes in his artistic career, ranging from his time in Yale's painting program to a rather traumatic stint at First Second to his decision to prematurely end The Bunker, his critically acclaimed, creator-owned Oni Press series with writer Joshua Hale Fialkov. He speaks with well-articulated candor punctuated with painful emotional observations, reminiscent of the way his formally assured art style often breaks into frenetic, impressionistic blurs in key moments.

These days, Infurnari seems to be enjoying a less stressful period in life as he works on the epic body-horror mystery Evolution for Image Comics. We spoke with him about his tumultuous career and what he's got planned next.

Patrick Dunn: Is ["So What That You Can Draw!?"] actually out yet? I saw it was supposed to be released in 2017, but I couldn't find too much else about it online.

Joe Infurnari: Yeah, because I'm the worst self-promoter/non-businessman ever. What it boils down to is I did that to try and get it done for TCAF last year. It's very personal. I wrote it up, did it, printed it, and then I got really insecure about it, so I haven't promoted it too much as a result. It's kind of a weird thing. My relationship to writing is kind of complicated. It's really a confidence issue.

And I assume that project was especially insecurity-inducing because it was so personal.

Yeah. It was about this friendship-ending thing that happened a few years ago. There was a big fallout with a friend of mine of many years, like my best friend, and people who know you well know how to get under your skin. So one of the accusations, one of the things that was said, was that I have no ideas. I took that as a challenge and went through my sketchbooks. At the end I tried to make the case that the drawings I like the best have the most psychological depth, so why not grant that psychological depth to people in your real life? When you do that, you not only have better, more complicated characters – a.k.a., your writing is better – but you grant more room for other people to be flawed and make mistakes as well.

What was the inciting incident there? What prompted your friend to go off in this rage about how you have no ideas?

What was the inciting incident there? What prompted your friend to go off in this rage about how you have no ideas?

It's not in the sketchbook itself, but his father had died. This is one of those really tough situations. He was taking care of his father who was in many ways kind of an invalid, with one leg. His father was in his 70s and passed away kind of unexpectedly. If you haven't lost a parent, I can say for myself it was something beyond the pale for me to imagine. So he had lost his dad and I hadn't at that time. He was struggling as an artist. We knew each other in Yale in the painting program there. He felt that he should have been by that time already a famous artist. So we sat down and talked in my apartment and I was like, "What are you doing with your art?" I felt like he had kind of gone off the rails a little. He was always more successful than I was in it, and I had always held higher hopes for him than for myself with it, and it completely disintegrated over the last few years. So I said, "What are you doing? It seems like your position towards me as a viewer is really aggressive. It feels like a lot of these paintings you're doing right now are like a fuck-you." He took a great deal of offense at that because he in some ways was tying his work at the time into his father, so it felt like I had plunged a knife into his heart. And I of course never intended to do that. I was trying to talk it out. "What are you doing with your art? Let's get your art back on track," because I knew that had that fallen into place for him, it would have sustained him.

So then he just kind of flipped out and we just stopped talking and he would harass me every so often. The inciting incident in this book is an email I got from him in the middle of the night where he was saying, "Fuck you." It was crazy. He was attacking my mom for some reason, and he said, "If I ever see you, I'll fucking kill you." So that was the inciting incident for me.

So you obviously ended up turning it into something positive with this project. What was it like for you to write something that required a deeper level of self-reflection than anything you'd ever written before?

It was very raw and personal. Anytime I do any sort of writing, I feel very exposed, much more vulnerable than I do when I'm drawing. I had an agenda, I'll be honest. I felt that right now people are very quick to kind of flatten everybody out and dismiss them for this or that. "You're just a this," or "you're just a that," you know what I mean? "If you're not this, then you're that." I wanted to make the case that people are complicated and that's actually a good thing. It makes it harder for us to understand, it makes it less simple for your peers, but it's actually better. The drawings that had a little bit more of a psychological depth or hinted at kind of a psyche were more intriguing, so people who have a complex psyche should be a little more interesting because of that complexity. So by looking over these sketchbooks and looking for ideas and looking for some sort of narrative goals, I'm also looking to find character in some way, to also extend some larger berth for another individual. Individuals we interact with are better for having granted them that same level of complexity rather than flattening them out into whatever category you want to put them into.

You mentioned how raw and exposed writing makes you feel. You haven't done a lot of writing in your career. Is it because of that feeling?

You mentioned how raw and exposed writing makes you feel. You haven't done a lot of writing in your career. Is it because of that feeling?

Truth be told, it's because of a lack of established process. If I have an illustration to work on, I know how to do it. Before I sit down I can think of probably three or four ways to do it and different visual approaches. But the writing, I don't have 20 years of education. I didn't go to grad school for writing. I kind of have an excess of qualification artistically for what I'm doing, and I don't mean that to sound egotistical. It's kind of laughable, in fact. But as far as the writing goes, I feel around in the dark through that process.

You mentioned that library of visual approaches you can refer to. Having gone through the majority of your work, I was really struck by how versatile you are and how many styles you experiment with, especially in those earlier webcomics, which makes me curious about the influences that drove you into comics in the first place. What artists, what stuff were you reading early on that really got you interested in comics?

When I was a teenager I was interested in comics, and then the more manly of us get lulled away by the pursuit of the female. But mine was much more repressed than that and I just became obsessed with being an artist. Many years later, I find myself at grad school at Yale for painting, which was a pretty big accomplishment for this steel city kid from Hamilton, Ontario. My dad's just a laborer. My mom's a seamstress and a teacher. These are modest origins, and then I found myself at Yale. It was really a stark splash of cold water in the face when I got there. There was an almost universal opposition to meaning. I always had a lot of literary ideas and interests in the painting I was doing. Even when I got to Yale I was doing very art-historically related paintings. And there was a real opposition to meaning or content in that way. The expression, "Ideas are like assholes. Everybody's got one," was something I heard a lot there, which was kind of alarming. Unless you wanted to make paintings about paint, they weren't interested. And over those two years, through that friend of mine – Jason, who we've talked about the ending of that friendship – he kind of got me back on track.

I spent a summer in a prestigious art fellowship in Skowhegan, Maine. One of the great things from that summer was that I was really licking my wounds from my first year at Yale, and it was really refreshing to go there and get a different perspective on the whole art-making process. It was really expansive and inclusive there. And one of the things I came away with that summer was to plumb the depths of my adolescence a little more. What were the things that turned my brain on when I was a kid, that made me interested in doing drawing and art? And I found that it was comics again. So I then spent my second year in my research, in my own private work, reading a lot of comics, reading all the comics I didn't read in the interim since I had stopped following it. And also, not for nothing, my whole second year [at Yale] was the most ridiculous artistic project you could conceive of, which was to do a "sensitive barbarian" series of paintings. It was really like a big "fuck you" to the faculty. It was like, "Okay, I've had to talk about your shit. Now let's talk about mine." And it backfired for sure. They didn't respond well to it, of course. But I think there is something to having a little bit of an oppositional stance towards something that goads me to do stuff creatively.

So then I left Yale and was interested in comics and trying to integrate them into my artwork. I was included in this "Comic Book Idol" thing on Comic Book Resources. I think it was the second one they did, and I happened to get into the first round. I was one of the people that, if it was American Idol, I was one of the people with the really atrocious voices. That's how far I got in that contest. But it was validating enough to make me consider doing comics for real. It was probably another year or two after that that I was part of the Oni Press talent search. I think it was in 2005, and that got me my first paying job doing Borrowed Time with Neal Schaffer.

So you mentioned the comics that turned you on as a young person and the comics you went back and caught up on. What were some of those?

Well, I read Watchmen again because that loomed large. When I was a kid I had lousy taste. I had steel-town, head-banger, slightly flat-foreheaded soda-head taste. I liked Conan, I'll be honest. I took Krull in a pinch, but I liked Conan. So when I came back to comics I had to bone up on the literary stuff again a little bit. I remembered seeing Watchmen coming out at the time, but for whatever reason they didn't land in my hands. They didn't grab me. I certainly was aware of Maus as a kid, I was aware of Dark Knight, but I didn't read them. So I read them at grad school. I took in a lot of stuff. I took in a lot of Wally Wood, a lot of Eightball, a lot of Dan Clowes. "David Boring" was coming out when I was in grad school. There was a comic book shop just about a block away from the art and architecture school that I would go to every so often. It just opened my head up to some new stuff. In light of this interest in comics, I'd been doing basically these barbarian Conan paintings at grad school. I was just really exploring a lot of pulp culture, and if it was considered crap by my professors then it made it all the more appealing.

So after the Oni talent search, you worked for them for a few years before you went to First Second.

Yeah. I did a couple of books in the Borrowed Time series and I did one issue of Wasteland for them. So then at that point – I think it was around 2008 or 2009 – I was getting hooked up with a couple of guys at a studio in Brooklyn called Deep Six Studios. In there was Mike Cavallaro, Tim Hamilton, Simon Fraser, Leland Purvis, Joan Reilly, and Dean Haspiel. That was the thing that got me onto the webcomics, because they were involved in Act-i-vate at the time. That got me connected to real professionals, doing professional illustration. It was just really good to see how the pros were doing it, because up until then I was self-taught doing comics.

Somewhere in there, you did your first Big Two title, the Uncanny X-Men: First Class Giant Size Special, for Marvel in 2009. What was that experience like?

It was good. It was certainly very validating. It was nice to get paid more than I've ever gotten paid for my page of artwork. That was nice. At that time, Marvel was doing or had just started doing Strange Tales, where they were using independent artists to tell short stories. The second collection had Kate Beaton on its cover, so that gives you some sort of sense of it. It was really nice to be part of that, because this Uncanny X-Men book was supposed to have a little less conventional art and a little more playfulness with the character. It was a really nice experience. There was nothing negative about it I can say that would account for why I've never worked on anything again for Marvel. With DC I later did the Astro City issue as well as some coloring of a Superman story, but my big-toe dip into the Big Two has been very tiny.

How did you get connected with First Second? What was your experience like working on the two books you did for them?

How did you get connected with First Second? What was your experience like working on the two books you did for them?

The first book I did, [Mush: Sled Dogs With Issues,] was a dream project. The project itself wasn't my first choice. I did make a joke in the book, in my bio in the back, that I'm a cat person. And that's true. Working in that studio, at the time, Simon Fraser was working on a book for First Second. I think George O'Connor had already finished his Journey Into Mohawk County book for them. So there was a lot of positive chatter about them amongst my peers. There's something sad about the way artists now talk, because we talk about followers and we talk about publishers and we talk about editors. We don't talk about ideas. But at that time, we were talking about publishers, and First Second was a pretty good deal. You could get a significant advance and do a graphic novel. At the time they were the premier place, in our estimation, and Mush was a dream project. It couldn't have gone smoother.

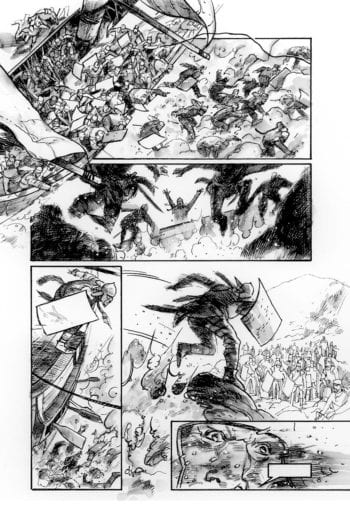

Unfortunately, Marathon really ended that. It was just a very difficult project for me on a number of fronts. It was too big a book for the size of book that we were doing. The writer, Boaz [Yakin], and I really lobbied for a larger-format book and I thought we got that. It was an already finished screenplay, and having read it, it was expensive and grand and epic. And it was going to be tough to get that under 200 pages. I think it was a 220-page script, maybe. I can't be certain of that at all. But it was a two-hour movie at least, and that wasn't going to boil down to 196 pages easily. So I knew I was going to have some smaller panels, and I thought we were going to need the small panels on the page to be bigger in print.

That makes sense. It does feel very condensed.

Yeah. Unfortunately it was a really damaging experience, because I was working really hard on the book to get it done. One of the conditions of the project was to have it done in time for the 2012 Olympics, because there was hope that they were going to dovetail with the Summer Olympics. I'll take responsibility for my share of things. I thought we were getting a larger book at a certain aspect ratio, and this was all approved from my end of things. I would never, ever go ahead on a wrong aspect ratio on a book. I'm not a newbie at this. So when I got the proofs, I was thinking that the book was going to have an aspect ratio that was taller so the pages themselves wouldn't be cropped, but they were. So it came down to that it wasn't plausible to re-layout the book for the other size.

I'm not a writer, so I sort of saw my emails as chats, and what I wasn't aware of is how that was creating the impression that I was really angry when I wasn't always. When I found out the aspect ratio of the book was going to be cropped at the top, yeah, I was angry. When I had to approve the color, when they invite me to come in and say, "Hey, you can look at this stuff, but don't ask for any changes because we don't have the time," those situations aren't ideal. But I know my emails probably made them worse, because I think they were probably receiving them with an impression that I wasn't intending to give, unfortunately. So the relationship soured.

But the long and the short of it has less to do with First Second and more to do with my takeaway, which was that I felt that doing graphic novels was not a very feasible way of doing things. I was working on "Mush" in 2008 and I think it came out in 2010, and the next thing I had that came out after that was in 2012. So there's no momentum in between books, and then you're really at the whims of the market and your publisher and their marketing ability. If the timing of the marketing doesn't click just right, you really only get two or three weeks, it seems, once that book is in the market. You've worked on something for over a year, and we're talking McDonald's sweatshop page rates when it boils down to things, which is not a complaint. It's so gauche to think that I would ever complain about that. But it's hard work every day for long hours. I was doing seven days a week, 10 hours a day, getting "Marathon" done. I was in physical triage trying to get that book done. I had disc bulges in my neck that had flared up, so I was basically having to go to massage in the morning and then work during the day. And I was having to take on large corporate projects to make ends meet to do this other book. So it just became an essay in how it wasn't feasible to invest a year in a project and have it drop into the market to no impression at all.

By 2013 I was kind of shifting gears to thinking about monthly comics. Dean and Seth Kushner and I were thinking of doing an anthology comics series. Again, the issue came up: Dean would write his and Seth would write his and he would be able to find an artist, no problem, and then it was me, an artist who wasn't too sure as a writer. So I said, "I'd feel more comfortable if we had a writer doing this." We approached Josh Fialkov at Baltimore Comic-Con around 2012 and then that transmogrified into The Bunker.

Which probably received the most attention and acclaim of anything you'd worked on up to that point, right?

Yeah, definitely.

What did that feel like for you?

What did that feel like for you?

Well, it was the best of times and it was the worst of times. In Christmas of 2012, my father was really sick. We didn't know it at the time, but he had mesothelioma. So the next five months were taken up until he passed away in May. But during that time Josh and I were working. The anthology book didn't materialize. But Josh said to me over phone conversations, "I'm just into this idea I have right now. It's five friends who are recent grads and they're going to go have their last hurrah and they discover a bunker in the woods with letters from their future selves about how they're going to cause the apocalypse." I'm like, "Fuck you, Josh, for having all these fucking ideas. Why don't we do that?"

Cut to maybe a month or so later. I'm in Canada, attending to matters with my dad, and Josh said, "There's already some media interest in this idea. We need to get something done for ourselves as a kind of proof of concept." So that's how the digital comics came about. I was working on them while I was tending to my dad. I lost him, but I had this really great project and time to direct towards something positive in my life at that time. I learned the hard way that feeling of losing a parent, and I very much realized how I had fallen short as a friend to Jason when he lost his dad. And that's also part of why I did this sketchbook.

So how long did it take for Oni to pick up The Bunker?

We started releasing it in 2013. We were in New York Comic Con in 2013 and we were talking to Dark Horse. We talked to Oni. We tried to talk to Image Comics. We talked to IDW. Coming out of that New York Comic Con, we had made the decision to move forward with Oni. So by December of that year, I was putting together the first issue. The feeling was that we were trying to keep pace with the interest in the story. For me it always feels like you've got to just dump it onto people. It's like, "You want this! You want this! Why don't you want this?" But in this case it was like, "Why do you want this so much? We can't keep up with you!" So I felt like I was chasing this tail of trying to get the book out there as quickly as possible, and I was doing it all at that time except for the writing. I was doing everything up to the lettering and coloring. So it was a lot of trying to meet the demand in those early issues.

Josh Fialkov is one of your longest-running collaborations and you guys told this relatively epic story together over multiple trades. How did your working relationship with him develop over time?

Well, I've been really frank with you, Patrick. It was really good, because we both come out of bad experiences with publishers. Josh had a big ordeal with DC Comics, so we had kind of bonded early on. Over the course of our relationship Josh was very much the adult between the two of us. I was struggling a lot with grief all the time, and the only thing that got me through that time was the sheer amount of work I had to plow through every issue. I didn't have a lot of experience with monthly comics, and the unfortunate reality is that they run out of steam. The sales drop off and it's not every creator-owned comic that can stay on the market indefinitely. I was losing money month to month. In light of that, with it taking me a longer time to do each issue even though I wasn't coloring, it was just getting to be a slog. It was just financially impossible when there were not going to be the quarterly returns anymore. The whole TV thing had gone by the wayside, and it was kind of a disagreement about "How many issues more do we do?" I wasn't prepared to do 10 more issues at a loss. Unfortunately, I struggled a lot under that pressure and I had a bad conversation with him and it's something that's still not repaired. But I have to be honest about my own end of things. I regret it, but I just know I couldn't continue in that way. Towards the end, I was looking to take on a second monthly to make ends meet on The Bunker. It was hard to realize, but that's not plausible. And when the one book – The Bunker in this case – is treading water, I can't make all sacrifices for that. I had to do something else. And coming out of that was Evolution.

So tell me about Evolution and how you came on board that project.

So tell me about Evolution and how you came on board that project.

It was at New York Comic Con again, probably in 2014 or 2015. I was pounding pavement, trying to put out feelers for some work, because I was trying to get a second monthly going. I was hounding people that probably didn't want to hear from me, and then I was talking to a good friend of mine, Ryan Alexander-Tanner. He was my best man at my wedding and he was out in Portland. I was just talking to him, saying, "I've got to make something else happen," and he said, "You should talk to Joe Keating." I think I reached out to Joe and he said, "Hold on, I think I might have something." I didn't hear anything for a couple days and then I got an email from Sean Mackiewicz over at Skybound, talking about Evolution. I was kind of interested from the get-go because it was pitched to me as a body horror book, and that's always something I've been interested in. Growing up in southern Ontario, Cronenberg was always an obsession of sorts.

You've got a different writer working on each of the three main plotlines in each issue of Evolution. Does that pose any unique challenges for you?

The script is already done for the whole issue when it arrives on my desk. John Moisan, the editor, does a good job of kind of keeping all of these cats corralled so when the script lands in my inbox it's already harmonized into the full issue. So that's easy. But at first I had to adjust per storyline, because you're dealing with different writers and it's a little bit different. But I think it was smart to have the one artist to make it a little more continuous between the storylines.

It sounds like Evolution is one of the better experiences you've had so far in your career.

Oh, yeah. There was a friend of mine when I was at Deep Six studios, this guy Nathan Schreiber. We were listening to Notorious B.I.G. and there's a line where he talks about eating canned sardines in one of his songs. Nathan made the joke to me, "I didn't know that Biggie was a cartoonist!" because I was living on canned sardines for a while. So this is our way of coping with the reality of eating sardines, and that's how we bridged the hope that one day we would be a Biggie of sorts. So in that environment of deprivation, it certainly is nice to not feel like you're penny-pinched and nickel-and-dimed up above you. And that's not a slight to any other publisher, because it's definitely the reality of a lot of publishers who aren't multi-million-dollar corporations. But in this case, thankfully, Skybound has the resources that it can afford to pay a healthy page rate. And they can have you work six issues in advance. So it kind of protects you a little bit from the knocks of the market. And everybody I've dealt with there has been really cool. It's kind of relaxed, not to say that other places are not. It's just been a good experience, personally.

Where in this process did the idea for the sketchbook start germinating? It sounds like it's been a few years in the making.

(Laughs) I probably fancied myself at a place in my career where somebody would give a shit in the first place. In the summer of 2016, my wife and I moved from Brooklyn to Toronto. We were both middle-aged with no friends and I had no connections to any of the community here at that time. So I was really keyed up for TCAF 2017. I knew that Evolution wasn't going to be out at that point, so in February 2017 I decided I was going to do it. I had a number of passes on it before it became what it ultimately did become. I got in touch with a printer in town here and it was a good experience all told, but I have done really nothing to promote it, which is something I'm not really happy about.

So what do you think you've come out with on the other end of that project, personally?

So what do you think you've come out with on the other end of that project, personally?

I can't say for sure that I have any increase in my confidence as a writer coming out of it. But I do think between the combination of that and working on Evolution, I think the next thing I work on is going to be something of my own entirely.

Is there a set endpoint for Evolution at this point?

I'm contracted for 18 issues. I can't say for sure what's going to happen, but I can't count on it going beyond 18 at this point.

Do you have any ideas yet for something you'd like to write yourself?

Yeah. I've been working on something for a number of years now. Because my own so-called writing process is mostly just a lot of absorbing scripts passively, what I've found I like the most is the laying-out process, because that's where I get to reverse-engineer some of the writing. I learn a lot doing that. Since working on "Evolution," now I feel like I need to do my own story. Because of my experience working on a number of scripts, I feel like I have a little bit of an understanding of the rhythm of an arc. Personally I'm kind of disturbed by the level of surveillance – I'll say in Canada as well, but I think it's mostly in the U.S. I think it's troubling, and I think it's troubling to think about how little people talk about it. Something I've been thinking a lot about is the ways in which we as artists self-censor ourselves out of the gate, because we know which stories we can't tell. We understand which stories are market poison. So I'm thinking of surveillance a lot, and I've been thinking of it for a while now. Since the election has woken up so many people to so many things, it really gave direction to that story that it didn't have beforehand. It's really come together quickly over the last year, so my plan is to have that ready before the end of the year.