Jean-Claude Mézières, who drew the future into the present, has died. He visualized the current breakdown of Earth's climate in 1969, and was responsible for essential parts of the blueprint for Star Wars over the following years. And in 1980, like a Zen master with his brush, he suspended the flow of time from the window of a Parisian café.

Born in 1938, Mézières is famous for his work on the comics series Valerian and Laureline, which he created in collaboration with his lifelong friend, the writer Pierre Christin. The two of them grew up in Saint-Mandé in the Val-de-Marne region east of Paris. They met in a shelter during an air raid in 1943 or 1944. Also crucial to the series was Mézières’ sister, Évelyne Tranlé, one of the great comics colorists of her generation.

Valerian’s first episodes of slightly big foot-humored science fiction and time-travel stories were published in 1967 in the legendary comics magazine Pilote, edited by the great humorist and co-creator of Asterix, René Goscinny. Very quickly, however, it developed into an epic saga, albeit an always very grounded one, consisting of 22 books as well as sundry ancillary publications. The main series ended in 2010.

The sensuality of Mézières’ brushwork, his visual imagination, and the sense of internal logic he brought to the fantastic creatures and concepts he drew were central to the series’ success. In 1981, after eleven books, the story came to a dramatic and bittersweet endpoint in Brooklyn Line, Terminus Cosmos. The voyage through time that had kicked off the series’ grand narrative in the early masterwork The City of Shifting Waters (serialized 1968–69, collected 1970) came to its natural conclusion as Valerian left the Manhattan docks for a Statue of Liberty enveloped in the haze of winter, fully aware of the imminent collapse of human civilization.

The breakdown of global ecosystems narrated in Shifting Waters was caused by a series of nuclear detonations in the 1986 of the story’s timeline. All very Cold War. However, Mézières’ and Tranlé’s unforgettable images of the quake and the hurricane that topples Manhattan’s skyscrapers as our heroes escape across a collapsing George Washington Bridge in a hovercraft feel uncomfortably topical today as we hurtle toward the tipping points that have become our markers of impending catastrophe. Shifting Waters subsequently describes a United States in disarray: police stations on fire; caravans of refugees negotiating collapsed highway; and the smoking embers of Yellowstone National Park. From the floating bubbles in which they have been captured, our heroes gaze into an erupting volcano: the sublime of climate collapse.

When Mézières drew Shifting Waters, he was already an experienced cartoonist and illustrator. Born in the Paris region, he was educated at the city’s noted applied arts school, École nationale supérieure des arts appliqués et des métiers d’art. There he met and befriended Jean Giraud—the later Moebius—and through the 1950s the two of them collaborated on illustration jobs and minor animation projects.

Having already received encouraging words via post from his childhood idol Hergé, Mézières travelled with Giraud to Belgium to visit other lodestars of their youth, including the virtuoso humorist André Franquin and the master of cartoon realism Joseph Gillain, better know as Jijé. Giraud went on to work for the latter as an assistant, but these encounters were also creatively significant for the young Mézières, whose style would become a perfect synthesis of cartoon humor and textured naturalism epitomized by these two Belgian paragons.

Absolutely formative was a period in 1965 which Mézières spent working as a cowboy on a ranch in Utah. He sent back drawn reports for publication in Pilote and other places, and also reconnected with Christin, who in the meantime had received his doctorate in comparative literature and had accepted a university teaching job in Salt Lake City. The States left an indelible impression on both, and helped inspire them to make comics together.

Both were avid science fiction readers, and the influence on their work by authors ranging from Isaac Asimov, A.E. van Vogt and Larry Niven to Jack Vance, Fritz Leiber and Philip K. Dick is evident. Additionally, Mézières absorbed the lessons of the great MAD cartoonists, especially the earthbound caricature and virtuosic hatching technique of Jack Davis. He filtered this through the more economical humor cartooning of Lucky Luke artist Maurice de Bevere, alias Morris, and the brushy elegance of Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella.

The result was Valerian and Laureline, the story of two spatiotemporal agents working for an intergalactic bureaucracy that keeps order across the timeline. This premise enabled Christin and Mézières to combine a wide range of influences, concepts and genres, from frivolous space opera to gritty science fantasy, with a healthy helping of evergreen tropes such as time travel and parallel universes - always with world-building a central concern and with great affinity for connecting their stories back to the creators' own present day, captured with rare, lived texture.

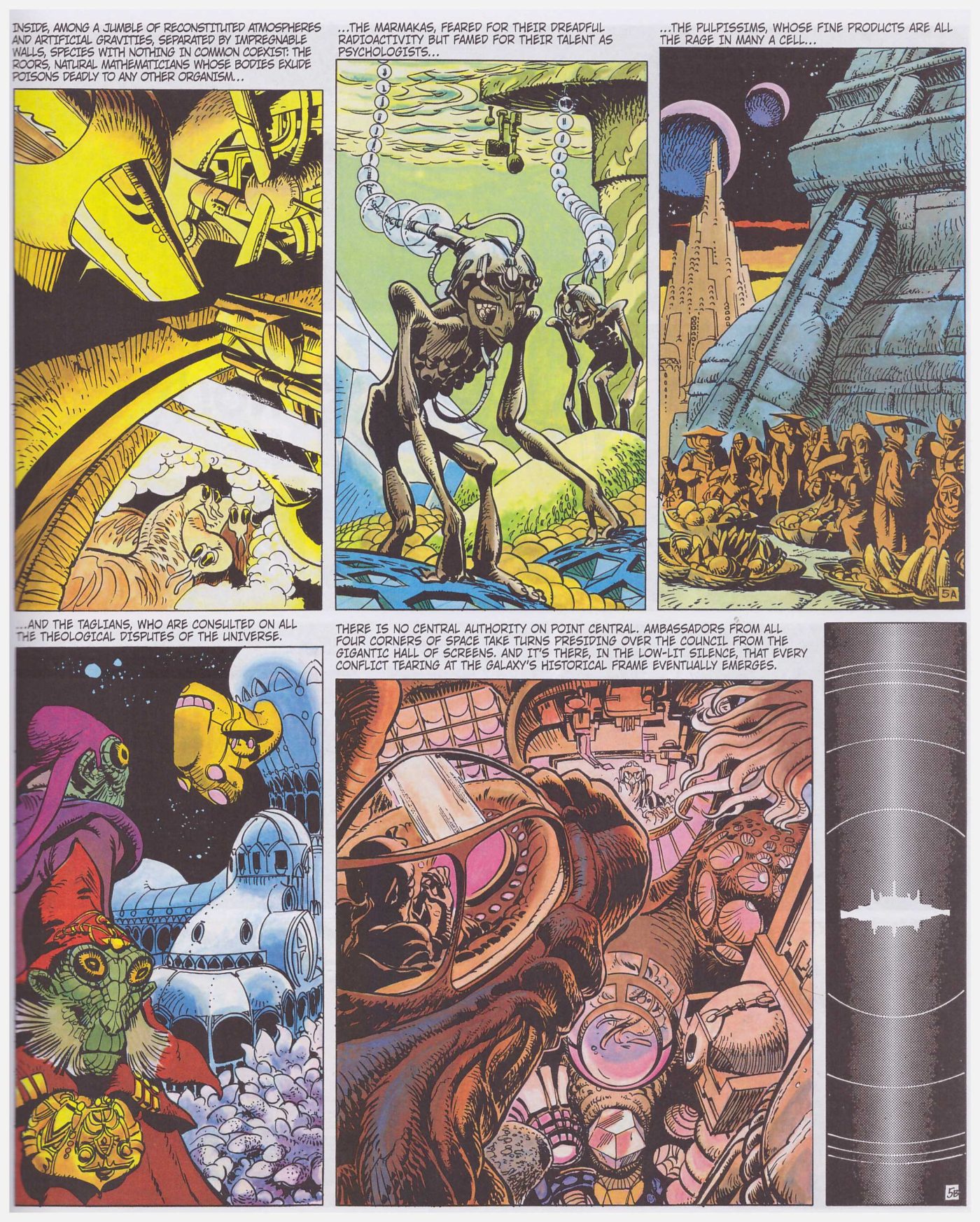

Mézières soon showed himself to be one of the prime xenologists of his generation: when he draws an alien life form—often in just one panel with no promise of ever appearing again—it feels alive with its own particular physiology, psyche, culture and history. The only contemporaneous peer I can think of in comics is the wondrous paroxysm of creativity that is Neal Adams’ work on Superman vs. Muhammad Ali (1978) - a book that was surely inspired by Valerian.

An awesome high point of Mézières’ storytelling vision is Ambassador of the Shadows (1975). It's sort of a political thriller, but really a travelogue of Point Central, the UN of intergalactic space-time - a kind of deep space Tower of Babel, where the species of the known universe congregate for intrigue and conciliation. It is a delirious romp through alien environments, at times decidedly hallucinatory in character, and a tour de force of imaginative cartooning. Among the creatures we encounter is the tiny and irascible hedgehog-like Grumpy Converter from Bluxte (whose fissile lower intestine multiplies all known currencies), and the charming trio of avaricious Shingouz - runty merchants of information that look like two-legged anteaters with bird’s feet and bat wings.

Our main characters, of course, are Homo sapiens: Valerian is the somewhat naïve and wavering but also impulsive hero who would never survive without the smarter, more morally-grounded Laureline. From the outset, the duo was a feminist statement from the two creators. And their science fiction often took the form of socio-political allegory in the spirit of the left-wing New Wave authors they were reading: issues treated included gender relations (The Land Without Stars; serialized 1970–71, collected 1972); imperialism and exploitation of native populations (Welcome to Alflolol; serialized 1971–72, collected 1972); fascism (Birds of the Master; 1973); and ideological (super)hero worship (Heroes of the Equinox, 1978). In that period, with the series at its height, however, it is so involving and visually immersive that any contrivance is soon forgotten.

It seems poignant that Valerian started deteriorating after the 1981 endpoint at the Statue of Liberty, mentioned earlier. Christin and Mézières lost their way trying to sort out the temporal paradox they had seeded with the apocalyptic scenario of Shifting Waters; their humor congealed and their allegories became didactic. Most depressing, however, was the dissolution of Mézières as an artist. Earlier, the apparent nonchalance of his inking and the texturing of his hatching were among his primary strengths; now he began losing his grip, becoming schematic, clumsy and uninventive. The 11 books that comprise the series’ second half are a study in creative decline.

All this matters little, however, because by the time atrophy set in, the two of them had already left an indelible mark on popular culture. I do not know if he has ever admitted it, but that cultural jackdaw, George Lucas, surely drew upon Valerian and Laureline when he created Star Wars. Not only is the movie series’ basic space opera-cum-high adventure carnivalesque very simpatico with the comics—from Point Central to Mos Eisley—but elements such as Han Solo’s carbonite freeze, slave Leia, or the unmasking of Darth Vader all appear heavily inspired by Mézières’ drawings. And the blueprint for the Millennium Falcon is surely the iconic circular and similarly grungy spaceship operated by our two heroes - the one whose spatiotemporal hyperjumps Mézières so memorably depicted with zip-a-tone monochrome.

Mézières also worked as key designer on the messy-but-inventive spectacle that was Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element (1997), alongside Moebius and others. That movie was a step on the way for the French director to realize his lifelong dream of adapting Valerian and Laureline to the big screen, which finally happened with the self-produced and sadly soulless vanity project Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets in 2017.

Valerian and Laureline is consistently satirical and critical of human civilization, but ultimately founded in a belief in our ability to save ourselves. It is a work steeped in the idealism of '60s Marxism and the utopianism of the hippie movement. When Mézières draws an overgrown tenement in New York’s East Village bathed in the afternoon sun, or when he unfolds a stampede of bison along the foothills of the Rocky Mountains during a thunderstorm, he does it with a deep love for the power of nature. When he and Christin project an intergalactic human civilization, centuries after its collapse in our time, it is in active spite of our self-destructive impulses in the tradition of classic utopian science fiction. And it is an important motif of the series that Valerian and Laureline rarely, if ever, resort to real violence.

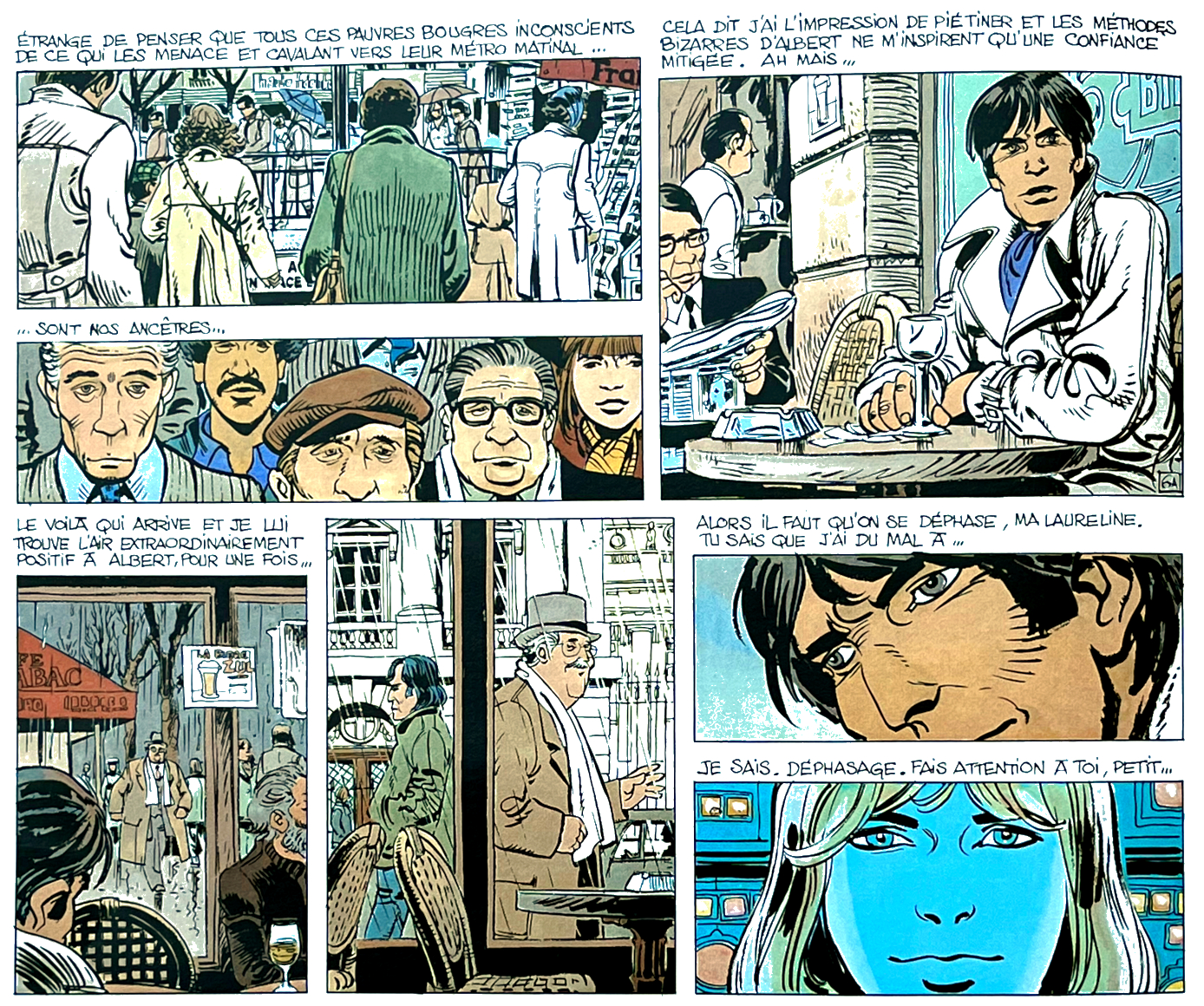

As mentioned up top, the 1980 book Châtelet Station, Destination Cassiopeia finds Valerian stranded at a café at Place de la Nation: drunk, tired and directionless. He is ‘phasing’ telepathically with Laureline, who is floating along a subterranean geometry of corridors on an alien planet in search of answers to the riddle that threatens their civilization.

The powerful, romantic sense of longing here is acutely tempered with hopelessness, but the moment lingers on the page in its sensory beauty. Valerian looks through the window at the passers-by, seeing his ancestors move along their paths ignorant of the impending apocalypse. His journey through time to the reader’s now is thus cleverly marshaled as a critique of civilization, but at the same time—and more basically—it is used to evoke the sense of time as an illusion. One of those rare moments when our fear of death recedes as we look into eternity.