Born: January 7, 1945, Orange, New Jersey

Died: March 5, 2017, Candor, New York

Jay Lynch — cartoonist, satirist, and counterculture archivist — died from complications of lung cancer on March 5th. His career spanned more than six decades and made full use of his many graphic talents. He contributed to the earliest counterculture press, drew and edited many underground comic books, designed confectionary novelties and promotional products, and in later years painted a myriad of private commissions for fans of his work.

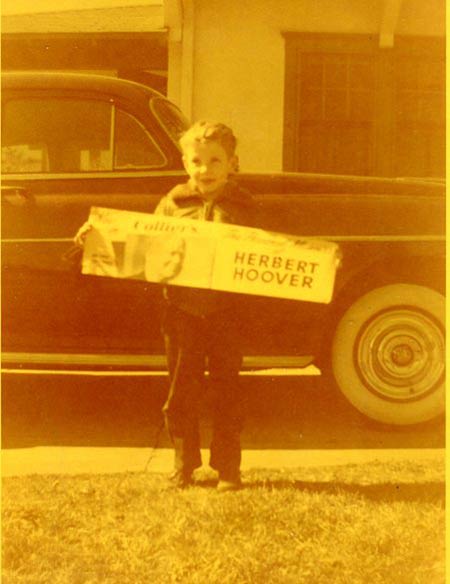

Jay Lynch saw himself as a cartoonist even when he was just a young whippersnapper. He liked to draw. He liked funny stuff. It just made sense. He enjoyed the strip There Ought to be a Law!, which appeared in his local paper. He noted that the cartoonists, Al Fagaly and Harry Shorten, invited readers to send in gag ideas, maybe events from their own lives, that could be adapted for the two-panel strip. The first panel set up a situation that required quick action, and the second showed how their best efforts went awry. The name and address of the person who suggested the joke was included in the strip. Lynch sent Fagaly and Shorten dozens of ideas but none of them were ever used. Rejection, he soon realized, was part and parcel of a cartoonist’s life, and he accepted that.

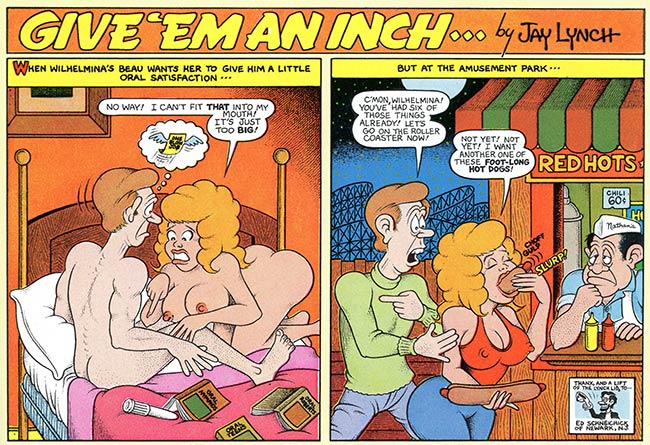

Many years later, There Ought to be a Law! provided inspiration for his Give ’Em an Inch series that appeared in Playboy during the 1980s. Similar setup, same sort of payoff, but with many more naked adults.

Lynch first sold gags to Cracked magazine while a student at Norton High School in Miami. In 1963, he left his home in Florida, moved to Chicago, checked into a cheap hotel, and got a job as a lingerie stock boy. It was all part of his master plan to earn big bucks in the exciting field of cartooning. He attended art school at night, sold gags to Sick and Cracked, and contributed cartoons to a network of college humor magazines and satire publications, including The Realist. He was a frequent cover artist for the Chicago Seed when underground papers first came to Chicago and also appeared in the Berkeley Barb, East Village Other, The Fifth Estate, and many other members of the underground press syndicate.

He was a key figure in the underground comix movement, producing eight issues of Bijou Funnies with his partner-in-crime Skip Williamson. They were a vital part of what became one of the most revolutionary art movements of the 20th century. Lynch contributed to numerous other underground titles like Bogeyman, San Francisco Comic Book, Bizarre Sex, and Teen-age Horizons of Shangri-la. The last issue of Bijou Funnies, an homage to Lynch’s favorite satirist, featured Harvey Kurtzman-style parodies of popular underground comic characters drawn by other cartoonists.

After the underground faded he moved into commercial work, overseeing the production of celebrity sticker books and fast food giveaways. He drew cartoons and illustrations for Playboy, Oui, and other men’s magazines. His juvenile sense of humor was also in high demand at Brooklyn’s biggest bubble gum manufacturer, Topps Chewing Gum, who hired him to design cards and stickers, which prominently featured puke and booger jokes for Garbage Pail Kids, Wacky Packages, and many others. In recent years, he has worked on public interest campaigns, illustrated children’s books, and designed covers for the last remnant of the underground impertinence, Mineshaft magazine.

His personal archives are stored in his home in a small town in upstate New York, where he moved in 2000, and include every letter he ever received since 1958, every publication in which he has appeared, file cabinets full of notes and rough sketches, and extensive collections of humor magazines. He bequeathed his property and belongings to the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at the Ohio State University.

Before he died, I had several conversations with Lynch about his end-of-life plans. He wanted to stay alive long enough to ensure that his will transfers his whole estate to the Billy Ireland Museum and that his creditors are paid in full, so no one can make a claim on his home. He bought his own casket and funeral package and was interred at Maple Grove Cemetery in Candor, New York. He told me he wanted a tombstone with a coin-operated fortune-telling device on top to pay for perpetual maintenance of his resting place.

“I’m thinking of a Magic Eightball-type-of affair, where you can ask a question,” he explained. “You put in a quarter and it answers it with a Magic Eightball type of answer. They won’t have quarters in the future, but some credit system. I don’t know. Something that maintains itself.” If any hardcore fans of Jay Lynch want to fulfill this eternal wish, please step forward.

He left no close family, two ex-wives, no children; he believed his life’s greatest accomplishment was the creation of an archive that spans the whole Beatnik-Hippy-Punk-New Wave-Alternative-Millennial counterculture. He accumulated a big pile of paper over many years, and it brought him great satisfaction to know it will be part of a proper repository of comic lore, The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. Columbus is also a less likely target for terrorists in the future compared to our major metropolises, he noted. “Billy Ireland’s new building was built by the Army Corps of Engineers and is nuke proof. It goes very deep below the ground.”

Lynch was an old-fashioned graphic artist, with the know-how to make things work in the printing industry. After several decades as inkslinger for hire, he became a repository of arcane printing processes, discontinued art supplies and materials, and forgotten production methods. Eventually, he became the go-to guy when it came to obsolete printing technology. He readily adapted to computer design tools in the 1990s, but if you were printing a million sticker books on a giant Webb press and the color was a little off, you’d want Jay Lynch with his knowledge of halftone color separations and chromatic charts to be in your corner.