This interview initially ran in issue #153 (October 1992).

Of all the EC artists, Jack Davis found the greatest success later in life — he is one of the country's premier illustrators with a style that is instantly recognizable. This interview was conducted in 1985, and since then, Jack Davis has moved back to his beloved Georgia, and William Gaines and Dik Browne have passed on.

THE EARLY YEAR OF BITTER STRUGGLE

LEE WOCHNER: Have you always been attracted to art? Did you ever imagine that one day you would be a professional artist?

JACK DAVIS: When I was in grammar school, I would copy Henry and Popeye and Mickey Mouse and the whole bit. And in high school, I drew for the school paper. Then, when I was in the Navy, on Guam, I drew for the Navy paper in the Marianas Islands, and when I was at the University of Georgia, I took a little journalism and contributed to their paper. And then I struck out for New York. I didn't graduate from Georgia. I came up through the G.I. Bill and went to the Art Student's League at night, and looked for work during the day.

WOCHNER: When did you first become involved in EC and how did that come about?

DAVIS: When I first came to New York I was going to art school at the Art Student's League and I was also looking for work during the day. I was trying to get to the newspaper syndicates. I had a strip and [the syndicates] would say, "This is bad," or, "This isn't so good," and I was really starting to get down on everything. I had finally gotten a job with the Herald Tribune inking The Saint via the school I was going to — the Art Student's League — and that didn't last too long. So, I started going into the comic book bit, and I went down to EC, which was way downtown, not uptown, and just walked in and met Al Feldstein, who was the editor. Al liked my work. And it was through the horror bit that I got started. They'd give me work, and I'd take it home, do it, bring it back, and they'd pay me, and I'd pick up another story. I'd do that about once a week. That's how I started. They liked my work. Finally...! After I had gone all over New York! It just so happened that EC liked what I did. I was about ready to go back home [to Georgia], I'll tell you.

WOCHNER: What year was this?

DAVIS: I was married in 1950, so it was somewhere around there.

WOCHNER: How long did you look for work until you wound up at EC?

DAVIS: Only about a year.

WOCHNER: I have to ask you about this story because it's so amusing. When you first came to New York — you were 20 or 21 — someone sold you a diamond ring?

DAVIS: Oh yeah. Some people down home knew that I was up here and they came up to visit me. They gave me tickets for a Broadway show because they couldn't go, so I went by myself and I was thinking about getting married ... I was engaged... I came out of the theater and was walking down the street and this guy comes up to me and says, "You want to buy a ring?" and I said, "No way, forget it," and he says, "This is a real diamond, it cuts glass. I was in the Astoria washroom and somebody had left a man's diamond ring." He showed it to me, and it was a man's ring with a big old diamond in it and he said, "Let me show you how it cuts glass." So we stepped over on the side and he took the ring and made a big mark across the storefront window — a big scratch — and he said, "How much money do you have on you?" And I said, "I have 35 bucks." And he says, "O.K., I'll give it to you for 35 bucks," so I took it. I walked home practically backwards — I lived up near Columbia, and I knew that he was going to try to knock me in the head and take it away from me, or something. I ended up staying up all night looking at it under the lamp... it looked good to me. I went to school the next day at the Art Student's League and these guys who grew up in the area said, "It ain't worth a dollar..." [laughter]. And it wasn't.

WOCHNER: That was your last 35 dollars, right?

DAVIS: Yes. The last that I had on me.

WOCHNER: That was your first education in New York City?

DAVIS: Oh yeah. And then I had my automobile stolen. I came up from school — I had a convertible Chevrolet — and had made some good money working for Coca-Cola in Atlanta, so I had bought a car, a used car. I came up here and drove it all the way up. I came up on a Sunday and went through New Jersey. This was before they had the turnpike. I came through Camden... I could see the skyline of New York off in the distance and traffic was pretty bad. I guess people had come back from the beach. I went through the Holland Tunnel, came up, went over the Brooklyn Bridge, and wound up in Brooklyn! Got lost looking for the YMCA, 'cause my mother made reservations for me at the YMCA. I finally found it. While I was staying up there and trying to find a place to live — I found the one on 104th Street — I had a date one night with a girl over on 5th Avenue — Central Park, a real nice section. I went to pick her up and I took the key out of the ignition... and I came back and there was no car. I thought maybe the doorman or someone had it picked up, so I ran around asking everybody, "Did you have this car picked up?" So I called the police and the police said, "We can't do anything unless you come to the precinct and give us the whole rundown." By the time I got a taxi and went to the precinct, the car was long gone, and by the time they found it, it was in Buffalo.

WOCHNER: How long had you been in New York when this happened?

DAVIS: Oh, I guess three or four months.

WOCHNER: Was that about enough to get you to go back down south?

DAVIS: Getting pretty close. Yeah.

WOCHNER: And work was tight, right?

DAVIS: I think now there seems to be more openings for cartoonists and things like that. When I came up here there were no cartoonists at all except for the syndicates and comic books and there weren't that many of them. The syndicates were pretty tight with who wrote for them. Now we've got a whole lot of syndicates and a whole lot of people working for them.

WOCHNER: You mentioned a comic strip you were taking to the syndicates. Was that Beauregard, or did that come later?

DAVIS: No, that came later, after EC broke up. We went out on our own. In my comic strip I did a football player who was gotten up in the clothes of someone like Li'l Abner, except he was real ugly and big and strong, and I wrote it myself. It was just no good [laughter]. I had been drawing cartoons at the University of Georgia when I was down there studying art and everything, and I did all right.

WOCHNER: Why did you think it was no good?

DAVIS: He was grotesquely drawn, that's all! And that's where I feel the horror came in... and, then again, it wasn't funny. I thought it was funny and then other people read it, and there was no laughter, so forget it. So I stuck to drawing rather than writing. And that was about it. And then I was involved with Ed Dodd doing a strip for him that he was trying to sell, and it never did go, and all that was on speculation. That was a good lesson. I learned to never do that again. I thought it was ready to go, and then it wasn't. And then I tried Beauregard. I wrote that myself. I thought I'd learned a little more, and some of it was fair, but most of it wasn't.

LIFE AT 225 LAFAYETTE ST.

WOCHNER: What were your early days like at EC?

DAVIS: Well, I'd go in and pick up a job, go home, and do it and bring it in. I'd only meet with the editors when I'd come in like that. Al Feldstein was the editor who [I worked with] at the very beginning. And Al was Al. He was very businesslike. I was impressed because they were impressed with my work, and that made me respect them a lot. I was about 21 or 22 years old, and I looked up to them. It was not like going into the office and working with them every day. I've always worked that way — by myself, at home — and I've never been in any office, or employed by anybody. But EC was a good account. I stayed with them.

WOCHNER: What were the EC artists' reactions to Fredric Wertham's charges that comic books were corrupting America's youth? What was the mood around the office?

DAVIS: Well, I lived up in Scarsdale, N.Y. I'd see the issues come out... the horror bit didn't upset me too much because I enjoyed drawing scary things. Then, all of the sudden, some of it was really getting a bit grotesque, but they were paying me, and I was doing it. Then they had the investigations, and Bill Gaines had to go down to Washington D.C... So I felt that we were evidently doing something wrong. I felt pretty bad about it, I really did. I think I had a lot of old comic books up in the attic, and one night we just burned them. 'Cause I would hate to think that I had frightened some kid. Nobody likes to think things like that. But at the time I was doing that, I didn't think that it would get that kind of exposure, and it did. Nowadays, publishing has all kinds of pornography and stuff being done, and nobody does anything about that, but they did clean up the comic books and I had to go with it. But it was always frightening to think that I could be out of work because, well, what else was I going to do? I was drawing horror, and that was the one reason people were buying EC: to get the horror. The other titles didn't do that well. And that's where MAD came in. They had to come up with another magazine, and that's when Harvey stepped in with MAD. It was a funny book, a satire book, and that kept EC going.

WOCHNER: If I shoot some names at you, maybe you can give me some profiles about what you remember of them. Bill Gaines...

DAVIS: Bill was always just a very generous person. He was a big guy. I think he's kind of shy, but he's his own man. He's full of a lot of love for people. He's just a very giving person, and he's a good businessman, and I respect him an awful lot. If it hadn't been for him, I probably wouldn't be where I am now. I might be somewhere else, of course, but I like where I am now and I owe it all to Bill. There's a certain chemistry we all had with the horror bit. He enjoyed the horror bit, he enjoys his humor, and he enjoys having a good time... and it's a family thing. I think that when people come in from the outside, be it a writer or an artist, it's pretty much a compliment because he's the one who says, "OK, bring him."

WOCHNER: Al Feldstein...

DAVIS: Al is the guy who gave me my first job and I think he's a very good editor. He makes sure that everything runs right, that deadlines are met, and he's put me on the carpet quite a few times for being late, and I've never had that from anyone else. I'll be late sometimes, but Al really used to chew me out, and I needed it. I think, also, he was a genuinely good man, but he was concerned about MAD and running everything right, and he did it that way, and expected in return that you do a good job and not lay back. Every time I'd bring something in, he'd say, "Well, you didn't knock yourself out on this," and I didn't — sometimes I would, and that would make me mad, but that's an editor, and that's his job.

WOCHNER: Did you work a lot from his scripts?

DAVIS: Oh, yeah. All of the horror stories.

WOCHNER: Were his scripts easy to work from?

DAVIS: Yeah, because they would have a description on each panel, and of course my mind was going with the horror bit, which I liked, and it came off pretty good.

WOCHNER: Harvey Kurtzman...

DAVIS: Harvey is one of my closest friends. When I first came to New York, he and his wife invited me to their apartment. I was up from the South, and they kind of took me in as a friend. I'd eat supper with them before I was married, and after I was married, we'd get together and go out and eat. Harvey was kind of a low-key editor, but he was very hard. I think he's still one of the greatest talents when it comes to drawing. He could draw really, really well, and he did his thing but he could have done... I don't want to say better, but he had so much potential to do other things that he never really got a hold of. Whatever he did, like when he would do a story, he'd put every ounce of energy into it that he could. He would sit down and read the story with you, practically act it out, get you all the scraps that you needed, go over that with you, and when you walked out, you knew that he wanted a good job. He expected it.

Again, it wasn't the horror bit, and I liked doing the war stories, and I enjoyed working with him very much.

WOCHNER: Wally Wood...

DAVIS: I respected Wally for his art ability so much... He was an off-shoot of Harold Foster and Alex Raymond, and he was just a very, very talented guy — so far ahead of himself, and again, what he did with his life was his business. I respected him so much. I did not know him personally. The only time we would ever get together would be at Christmas parties at Bill's or at Halloween parties, things like that. I respected him very much as an artist.

WOCHNER: Now that you've mentioned that you feel that Wood followed in Hal Foster's footsteps to a degree, do you feel that you have inspired anyone to adopt your style?

DAVIS: Well, the only thing I see in my own work that comes out in others' work are my feet, my hands, all over the place and whether that's inspired somebody, I don't know. I do see a lot of my work come out in younger guys. I don't know, but I've always been inspired by other people. I do hands and big feet from other artists from way back.

WOCHNER: Who have you been inspired by?

DAVIS: Walt Disney. I think with all of his characters, the feet are big and the hands are very expressive. And again, I always loved Harold Foster's work, although he's pretty much of an illustrator, but his action is just unbelievable, and all of those great details! I think that when Harold Foster came out with his first Sunday page of Prince Valiant I wrote him a letter and he sent me the original art. I still have it. I haven't framed it, I'm afraid it might deteriorate or something.

WOCHNER: How about the Raid TV commercials? That certainly resembles your work.

DAVIS: No, I think the guy's fantastic, though. I'd love to draw like that, and if I drew that, it would be that way... But, whoever it is, it's good. I think he's an animator. It's that kind of Walt Disney type of stuff, you know, that rock 'em, hit 'em real fast, and big eyes and big mouth, and real quick movement. That kind of stuff doesn't animate too well. I've got a whole reel of TV tapes I've done. Some are real enjoyable — they're automatic, where the action doesn't move. The ones that move get to be kind of grotesque and hard to animate. When I do a cartoon for TV that's animated, like grotesque noses and things, it moves pretty well, and that I'm pleased with.

WOCHNER: What's the difference between your cartooning style and your animating style?

DAVIS: Well, I've got about three or four different styles, and when I do work, sometimes it's a loose style, like the bulging eyes and big nose, and some quick lines, and then somebody wants to see a realistic expression which still has humor. There's all types of cartoonists, like Bingham, who was with Punch, and Lowe, who was with Punch also. They're not Walt Disney type cartoonists; they're pretty much illustrators, but they will bring in exaggerated heads and feet and hands and these are to me the really true masters. Not old masters, but they were very big during WWII.

WOCHNER: Did you work hard to establish a cartooning style of your own, or did it just develop?

DAVIS: I think it just developed. I never really copied anybody else. I just love Walt Disney's animations and actions, and that kind of rubs off.

WOCHNER: Do you ever draw anything and then stop and say, ''Well, that's not really my style and I have to change it and make it my style"?

DAVIS: Once in a while, I'll get something where they want a pretty illustration, and I just don't enjoy doing that too much. I like what comes out of my own head.

WOCHNER: Bill Elder...

DAVIS: I just respect him. He could be a comedian on TV. He's a funny person, a nervous kind of guy, always coming up with something wild, and he was kind of the original MAD artist, because he'd put wild things in the background every time he'd draw something, and he'd put in crazy things that had never been done before. He always had a great sense of humor. I respect his painting ability. He is really just fantastic about that. Maybe Willy should have been drawing and painting and doing his own rendering — I don't know — but he was always sort of doing that. Now he works with Harvey. Harvey pretty much lays everything out for everybody anyway. All you have to do is just render it, so they have a good thing going there. I enjoyed working with Harvey on "Little Annie Fanny" in Playboy. That paid pretty well. It was security for awhile.

WOCHNER: You did backgrounds for awhile?

DAVIS: Yeah, and then it got to be where three or four guys were working on it, and I'd rather do my own thing, so that didn't last too long.

TIME MAGAZINE, ADVERTISING, AND BEYOND

WOCHNER: How did you break into advertising?

DAVIS: I started when EC folded. I needed money, and, again, EC had been a great showcase for me. I went down to RCA Victor and the guy there was a MAD fan. I got about three record cover jobs from them, and they paid about $300 a cover, which was pretty good next to comic book work. From that, it began to grow and then I met the man who was doing It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. He was a MAD fan, and he got in touch with me somehow. I don't know whether it was through MAD or not, but the billboards and poster work brought in a lot of money. All of the sudden, it was a different kind of work for me. I had a big campaign with NBC, and Gene Shalit was a big MAD fan, so that helped a good bit. Advertising is a lot more lucrative than the editorial or the comic book business. Agencies paid pretty good money.

WOCHNER: Was this the mid-'50s?

DAVIS: Yeah, I think it was the late '50s...

WOCHNER: Can you give us a brief rundown on some of the advertising work you've done? You've done a lot for automotive trade journals.

DAVIS: Yeah, well, what happens... a lot of this is trade magazines and consumer magazines, things like that, but one of the greatest things that happened to me was doing the Time covers.

WOCHNER: Was that your first? [Points to framed original of Time cover with Democratic donkey and Republican elephant.]

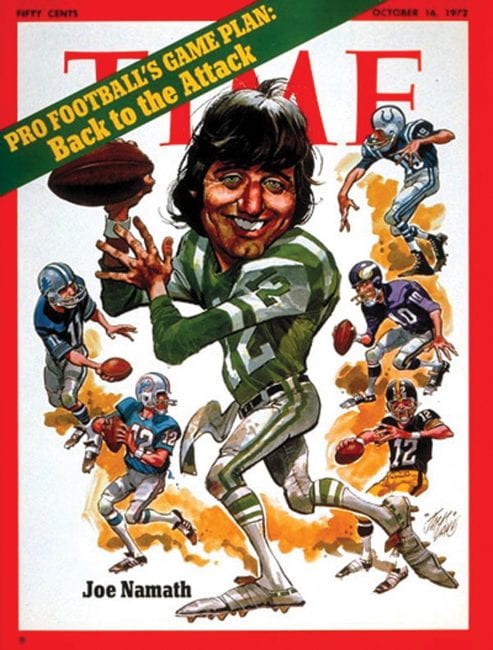

DAVIS: No, Joe Namath was... and I think that's my high water mark. I'm proud of that.

WOCHNER: You've done a lot of work for TV Guide also.

DAVIS: Yeah. Off and on. I think I had 36 Time covers. That's pretty good. I would have been happy just to have one.

WOCHNER: Pretty lucrative too, I would imagine.

DAVIS: Well, it paid pretty well, but again, not like advertising. The exposure was unbelievable. You were paid for just that Time cover and that's what I enjoyed. The covers back then, I think, paid $2,000... that's pretty good.

WOCHNER: How long would it take you to do a cover?

DAVIS: Well, they would call on a Monday and say, "Get ready, because this is what the cover story's going to be," and then on Tuesday they would come and say, "OK, this is the cover story," and then we'd go in and get some ideas. I'd go in maybe on a Wednesday and take maybe 10 or 12 ideas and they would pick one and I would wait until they picked it, and then they'd say, "OK, go with that," and then I would go home that night and bring it in the next day. Then it would go out on Thursday night and be on the newsstands Monday. So they really worked fast. Usually, they have about two other covers that are being done.

WOCHNER: Was that a watercolor?

DAVIS: Yeah. And I had to change the whole background. It was just going to be Joe Namath, and I had a lot of girls chasing him and cameras... that was in his heyday, and then, all of the sudden, he didn't do too well in a game and the powers that be said, "OK, let's go with an all-quarterbacks story." So we put all the quarterbacks in that were doing well then.

WOCHNER: Did you really do that in a couple of days?

DAVIS: Overall, the artwork, when I was actually sitting down at the board, took maybe about a day's work, but I would work that night, and then get up in the morning and finish it then and take it in.

WOCHNER: You've got a reputation for being very, very fast.

DAVIS: Yeah.

WOCHNER: Do you feel sometimes that you sacrifice quality for speed?

DAVIS: I think sometimes I do, really. Haste makes waste. But then again, once I get into the flow of working real fast and I'm doing it, then it comes off pretty good. Some of my best stuff is done the quickest. I have it in my mind and I picture it, and then do it. I can take something and start working on it and rework it and it just comes out horrible... but the other day I had to do seven frames for Pepsi-Cola — some slide production thing — and I sat down and whipped it out like I was doing the cartoons, and it came out great! But if I had to sit there and fiddle with it, you know... it works both ways.

WOCHNER: So you meet that deadline with adrenaline?

DAVIS: I do. The older I get the harder it is to get going. I used to work late at night, but I'll never do that anymore. I used to work sometimes on weekends, but I won't work on weekends that much anymore. But I'll get up at 5:00 in the morning sometimes, and it's hard getting up, but once I'm up, it's a pretty time of day and it's quiet. I get the radio going, and I have something done by 10:00.

WOCHNER: How much do you draw in an average day? Do you work five days a week?

DAVIS: Pretty much, but not long days. Like I said, I get up early — start work at 9:00, and work until three. I've been averaging an ad a day.

WOCHNER: Does your rep call you with these assignments?

DAVIS: Yeah. I get a call at 9:00 every morning saying, "There's a job coming," or, "This job is due..." I never discuss prices with him at all. He does all the pricing and all that, and he knows what it's worth — the whole thing. I just keep up with him.

WOCHNER: How did you find him?

DAVIS: He found me. They had two women who were working for Gerry Rapp's father back then, and also Gerry's dad at one time was asking me to do a lot of work, and I never really wanted to get involved with a rep because I always liked to be my own boss. I would always get calls, and so finally I [got a representative], and these unbelievable jobs would come in, and the pay would be great. I wouldn't have to work so hard, and I didn't have to go out and see anybody. I didn't have to wait for pencils to be approved. It was one of the best things that ever happened to me. I recommend it to any young person who's really got talent... there might be bad reps, but I have a very good rep.

WOCHNER: So, basically he'll call you up and say something like, “I need a rough of Joe Namath. Give me a few ideas and send them over...”

DAVIS: Usually he'll send out a worksheet, a work-order, with a layout that the art director has done — a rough layout of exactly what he wants — if it's going to be in black and white, or color, and the size, the date that it's due, and all those things. I'll look at it, and it'll say, "Pencils are due next week," or whatever, and I'll get on my telecopier and send him the pencils, and then he takes it to the client, and they OK it, and if there are any changes, he'll send them back over the telecopier, and let me do the changes, and then I'll do it.

WOCHNER: You're really a product of the 20th century.

DAVIS: Yes, and it's going to get better! I mean, there are ways of copying things better, but this machine is just unbelievable. I can take it with me wherever I go, as long as someone else has the same machine to pick it up.

WOCHNER: In The Art of Humorous Illustration, Nick Meglin says that you're a real procrastinator.

DAVIS: Oh, yeah. I'll get a lot of jobs, and work at them. Each one is procrastinating, but they're all piled up in a week. I'll pull them off — say, if I get up, punch the clock, get up early in the morning, sometimes just go at it each day and do it. I'll let a MAD job go until a couple of days before it's due, and then I'll jump on it. And I know I can do it.

WOCHNER: There's an anecdote about you going on a fishing trip and then realizing you forgot an assignment...

DAVIS: I took some bubblegum cards with me that I was doing for Topps and I hadn't finished them, and I took them with me because they were little things that I could take with me in a pack —

WOCHNER: You were drawing them at actual size?

DAVIS: Yeah... not too big. I took them with me when I went to New Hampshire or somewhere to fish, and I was going to take them to the post office the next day, but the mail up there is so bad, they were probably late. But I do remember sitting out in front of the headlights of the car inking because I'd forgotten to bring a lamp with me. [Laughter]

WOCHNER: What have you been doing lately?

DAVIS: I just finished a book for a publisher out in San Francisco on alcoholism. It's a good book. It's not a book, but a pamphlet, like a comic book, that will be distributed to offices and people who might have a drinking problem. Also, there's another book about alcohol in the home. Other than that, I've had this thing for Pepsi that I'm doing, and the cover for the Westchester Classic Golf Program. Every week is something different. I'm doing something for an insurance company with sports in it, and I never get to do sports. I love to do sports. I go crazy doing sports.

WOCHNER: Do you have an agreement with your rep as far as assignments you won't take or that you don't want to do?

DAVIS: He knows my work so well. He knows what I like to do and what I can do, so that's never a problem. The other day MAD sent me out something that was a take-off on Coke or Pepsi, and I said, "I can't do that!" [laughter] Because I've done ad work for both of them. Other than that, I don't go in for the preaching editorial bit. I do my thing.

WOCHNER: Are there any kinds of assignments you really don't like?

DAVIS: I don't want to do the sex thing. Hefner, that bit with him, even when I did cartoons for him, I would do cartoons that were funny but that didn't have sex in them. That's one of the things I kind of stay away from. I don't want to get into any real controversial thing either.

WOCHNER: Do you think it's an easy laugh? The sex motif?

DAVIS: I really don't read the gag cartoons in Playboy. Could be, and then again, I think TV and a lot of the stuff now — when someone gets knocked down and stepped on, people laugh — all the humor's kind of gone. It should come back. There's a comic-strip out now that I think is one of the greatest — The Far Side.

WOCHNER: Yeah.

DAVIS: That's the greatest thing! Here's somebody fresh, and the art is just beautiful. It knocks me out. I show it to my wife and she won't grasp it. But I just love it! It's humor, it's just unbelievable. And I love Dik Browne's Hagar the Horrible. I love B.C. and The Wizard of Id.

WOCHNER: How do you feel about Doonesbury?

DAVIS: I think Garry Trudeau is probably a good writer. I really don't know. Again, I don't like to see people preach stuff like that in cartoons.

WOCHNER: Did you ever get the urge to go back into newspaper comics?

DAVIS: Yeah, but I think I'd have to write it myself. It would take up too much time to be involved with somebody. What I'd like to do someday is to do some humorous books on my own, but I haven't had time. I'd like to do one on golf. I'd like to do one for kids. Just humor, different things.

WOCHNER: And write them on your own?

DAVIS: Yeah. If I could be that funny. I could draw some funny situations, but I wish I had the ability like the guy who does The Far Side — he's just so great.

WOCHNER: You don’t think you're a good comedy writer, then?

DAVIS: No. But I can appreciate good things.

WOCHNER: How did you get involved with the Children's Television Network?

DAVIS: Again, probably through MAD. One of the editors was a MAD fan.

WOCHNER: What did you do for them?

DAVIS: I did a Sesame Street calendar. I met Jim Henson, which was a great thrill because I think he's a very talented guy.

WOCHNER: Did you work directly with him?

DAVIS: No, we talked over the phone about the puppets. I think that every time someone draws his puppets, he wants to make sure that the colors are right. He's a real stickler for that. You don't go off and put legs on them. They've got to be just the way they are.

WOCHNER: Well, they're big stars.

DAVIS: Yes. And they've got to be perfect. My biggest reference is the World Book that I got for my kids when they were in grammar school. That has everything in the world in it, pretty much, but I really don't need references... people usually give me that, like when I do work for Time. I'll need a face and they'll come up with any kind of face I want.

WOCHNER: Is there anything that you'd like to do that you've never had the chance to do?

DAVIS: Maybe in a couple of years I'll retire and go down South to do watercolors of the areas. Go out with a camera and take some pictures of old shacks, as there's not many left, and old filling stations — things like that.

WOCHNER: In a couple of years you do intend to stop cartooning?

DAVIS: I'll never, never quit, as long as I'm drawing. But, then again, like I said, I'd like to try some of my book ideas. Gahan Wilson had a book out on wine. It was just one illustration per page and it was beautiful, just fantastic. I would love to do something like that. I'm not sure I could do what he does, but I'd like to try it.

WOCHNER: When you see a book like that, do you have trouble separating how you feel about it as a reader as opposed to looking at it from the artist's point of view?

DAVIS: No, I appreciate what I see. Everybody has their own taste. That Wilson book knocks me out.

WOCHNER: Do you ever miss doing comic book work?

DAVIS: I like to do cartoons, but... what I do miss I make up for with MAD because I enjoy doing MAD.

WOCHNER: What advice do you have for young artists just starting out?

DAVIS: I've given that a lot of thought. I think that you've got to enjoy what you're doing, first off. You have to have faith in yourself, believe in yourself. You have to have something to give. You've got to be dedicated to working. To really get started I think you've got to have good exposure. I would forget about all the money in the beginning and try to have whatever you draw printed somewhere, somehow, whether for the church, or the community, for the school, or whatever, but have your stuff printed in the local papers. That way people see your work and ask for it and pretty soon, they'll say, "What's it going to cost?" You bill and keep on billing. Exposure's very important. The main thing is to enjoy. I love to make other people laugh and see them enjoy what I do, too. I get a kick every time something of mine is printed.