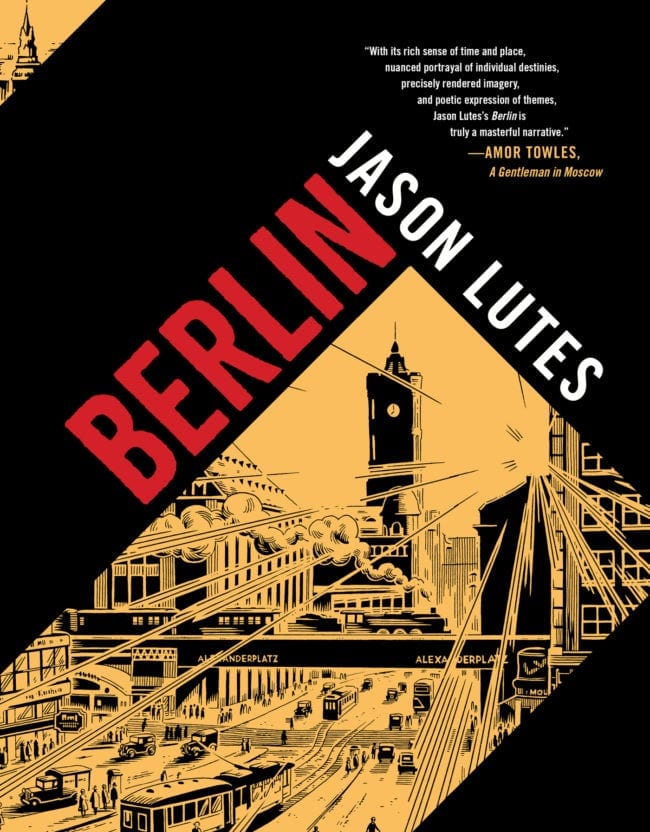

Jason Lutes has spent the bulk of his career on Berlin, an epic graphic novel released regularly in pamphlet form. The narrative, starting in 1928 Berlin, spans the demise of the Weimar Republic and Germany’s descent into Nazism. Now that everything is drawn, and the book is finally complete, it is arriving in a political moment that it is almost inconceivably well suited for — totalitarian leaders are popping up seemingly everywhere.

Jason Lutes has spent the bulk of his career on Berlin, an epic graphic novel released regularly in pamphlet form. The narrative, starting in 1928 Berlin, spans the demise of the Weimar Republic and Germany’s descent into Nazism. Now that everything is drawn, and the book is finally complete, it is arriving in a political moment that it is almost inconceivably well suited for — totalitarian leaders are popping up seemingly everywhere.

Lutes is a professor at the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, Vermont, one of the few comics MFA programs in the country. He taught me a little less than a decade ago and I served as his teaching assistant. September 4th saw the third and final volume of Berlin, called City of Light, as well as a nearly 600 page omnibus collection, released concurrently. He will be touring the book in the fall and beginning a new project that we discuss throughout.

JOSH KRAMER: Berlin has been a big part of your life for so long. What was your life like when you started working on this?

JOSH KRAMER: Berlin has been a big part of your life for so long. What was your life like when you started working on this?

JASON LUTES: I was living in Seattle Washington and I was very close to finishing Jar of Fools, which was my first book of length. And I was living in this apartment with two roommates and I, at this point, I think I'd quit my day job. I was art director of The Stranger, this weekly alternative paper in Seattle. So I was trying to make a go of it as a starving artist.

And there was an ad in a magazine for a book of photographs called Bertolt Brecht's Berlin and there was a little blurb paragraph description of the content of the book. So it was like this kind of colorful or suggestive description of Berlin in the '20s. And I just read this little blurb and I thought right then, “that's the next thing I'm going to do and it's going to be 600 pages long.”

How did you know you wanted to commit to something so large in the moment? Is that the kind of thing that you were doing a lot? Are you the kind of person that just is like, I'm going to commit to these huge projects and just see them through?

No. So the book that I just finished was one where I committed to doing a page a week, so that was the extent of the commitment. It was going to be improvised. I made it up as I went along. And then when it was done, it was done. The decision to draw Berlin, to make Berlin, was very impulsive. There's no conscious consideration. It's not like I'm stepping back and thinking, "well how long is this going to take me really?" Or, "What are the real implications? What does this mean for my career?" None of those conscious questions have entered into these kinds of decisions. It's like I get a feeling, like a sudden urge. And I make the call and then I just basically commit to it. And it's weird, obviously it's strange and people look at me funny when I tell them that. It's just true of my storytelling too. It's true with every level of my creative life, I follow my gut instinct. There's not a whole lot of higher-level thinking going on.

I mean, you know, I can do a thumbnail draft and I can write scripts if I want to. But in order to keep it alive and interesting to me, I as a writer don't want to know what's going to happen next. So Jar of Fools was very much a seat-of-the-pants experience. And I discovered the story as I went along. With this book, it was just a bigger version of that same idea with the restriction being that it was based on actual historical fact and there's real milestone historical events that occur along the way. I usually would write a chapter at the time, like a 24 page chapter at a time. I might write it all out, but then when I sit down to actually draw that page, as I'm drawing the characters within the panel I might look at a facial expression I just drew or look at their body language and change the dialogue to suit how they are in the panel. So I very much try to keep it open, to keep it flexible up until I actually start laying down the ink.

What were your main narrative inspirations for Berlin?

From a straightforward, mechanical, storytelling perspective, the comics of Herge, right? All of my basic “Comics 101” self-education that I got was from studying Tintin both growing up and then as an adult. And then once I sort of figured out the conventions that Herge was applying, then tinkering them and changing them and making them my own in a lot of cases. In terms of like tone, for Berlin specifically, tone and technique, I think I was I was thinking a lot about Wings of Desire by Wim Wenders, which I had seen in my early 20s, which was very affecting. And the novel Berlin Alexanderplatz by Alfred Döblin which takes a very kind of impressionistic view of the city at the time. And both of those works do a lot of drifting in and out of the consciousness of various people on the street. So those had a big effect on how I ended up telling the story.

And then beyond that I would have to say it's probably a combination of any number of indie films that I absorbed when I was in art school or after. I remember I watched a lot of Jim Jarmusch. Then I remember there was this one year at the Seattle [International] Film Festival where I had press passes. I would just go walk into a movie theater and sit down and watch movies for four hours, not knowing what they were going to be. I think there was a period there where I kind of just immersed myself in cinematic visual storytelling. I think Herge, Alfred Döblin and Wim Wenders would be the three big ones that were the obvious influences.

So you were plotting Berlin when you lived in a city, in Seattle in the '90s, but you've lived in a lot of places, right? I read somewhere you said that by 2009 or something that Vermont was the 18th place you'd lived since you've been an adult. What did it mean to you to be constructing this kind of elaborate historical city in your mind that you could put this book in?

So you were plotting Berlin when you lived in a city, in Seattle in the '90s, but you've lived in a lot of places, right? I read somewhere you said that by 2009 or something that Vermont was the 18th place you'd lived since you've been an adult. What did it mean to you to be constructing this kind of elaborate historical city in your mind that you could put this book in?

A sense of place is super important to me in any medium, at least any narrative medium that I engage with or read or watch. If a TV show or a movie or a videogame don't have a solid sense of place it's pretty easy for me not to care as much, and cities specifically. Growing up, most comics, aside from European comics, most American comics, like a lot of like Marvel superhero comics would be set in New York but they also had a kind of placeless quality to them. Like even within a given scene the way it was — the different angles that you'd see things from — it all didn't necessarily come together and create a believable environment that the characters were, whatever, having their fight in.

But then I remember films like Raiders of the Lost Ark was a big influence because there was such particular attention paid to the physical context and how to make those action scenes thrilling and more believable and more engrossing, Spielberg really had to put you there. And I think choosing how to shoot those scenes effectively makes them all the more convincing when you have some conception of what this space is. And it's an unconscious thing. It's not like I'm thinking about, "oh, I don't buy this. I don't buy into this physical space." It's just something that affects you on a deeper level than that. And for whatever reason that's just like a standard that I have and I try to bring into my stuff wherever possible. I think a lot about being in the world and my own physical surroundings and how I'm a part of them and how they influence me.

And cities specifically are fascinating because they are the result of collective effort and energy of humans coming together. But they grow organically even when you try to plan them ahead of time and have really careful overarching notions about how a city should operate, they'll escape that and they'll just kind of grow on their own. So I'm totally fascinated with cities as outgrowths of human community in all different aspects.

Is your view on cities something that you developed over time? Or is that something that changed over the course of working on the book?

Not of that stuff. I think that view was formed when I was in my early 20s. When I was at RISD I took a course — I think it was taught by a Brown professor — on basically how cities grow and evolve and it was the first time I sort of stepped back and looked at these kinds of environments. I was living in Providence obviously and at that point in my life that was the biggest city I'd ever lived in, having come from suburban California. It was just this revelation. If you don't know history or engineering or understand the markets of a given place then you might not understand why certain things end up where they do, why the railroad tracks are where they are, or what have you. We can infer, or imagine, or project into the crazy, complicated, dense, beautiful, ugly, all of that stuff that is a city or that grows up out of this confluence of all these forces. It's just endlessly fascinating.

It's not that any of that is evident in my book but while I made the book I thought a lot about it. And my next book is going to be a Western that takes place in Arizona in 1865 in the area of Phoenix, which at the time was just a collection of tents on a river. You know, the beginnings, the very early beginnings of what would one day be a sprawling city.

For Berlin, you were fascinated with this historical period but you were more interested in it as a stage for really interesting characters to kind of take over. Is that right?

I'd just come out of this previous book and I kind of felt like I understood how comics worked, and now I could tell any kind of story I wanted to. I had my footing as a cartoonist and I felt able to take on any kind of subject. Then I chose the subject and then I thought to myself, "Well what's it going to be about? Who are the people?" I did two years of research before I started actually drawing. And in that time allowed all that information from the research to kind of percolate through my, you know, whatever you want to call it, my system.

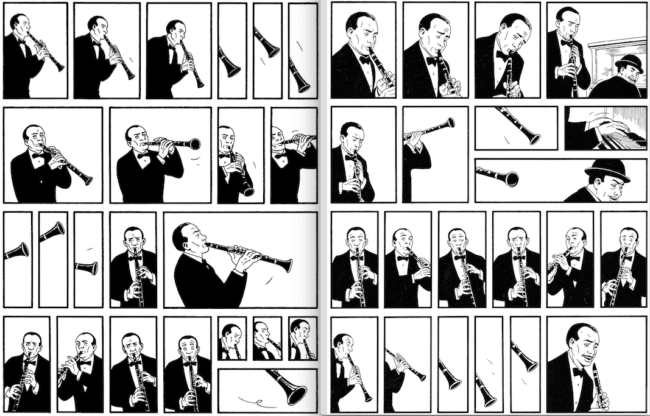

I had some highfalutin ideas about what I was going to get across, what I was going to "lay down." And I also wanted to explore as much of the kind of spectrum of human experience as possible using this medium. One of my goals was to see what I could do with comics. How do you convey emotion? How do you convey something like the sense of taste or smell? How do you tackle these sensory things? Every medium has its own challenges as far as those things go. And I was really curious about what I could do with comics. The conscious part was this weird combination of, "here are some big themes I want to address and here is the formal stuff I want to tackle with this medium."

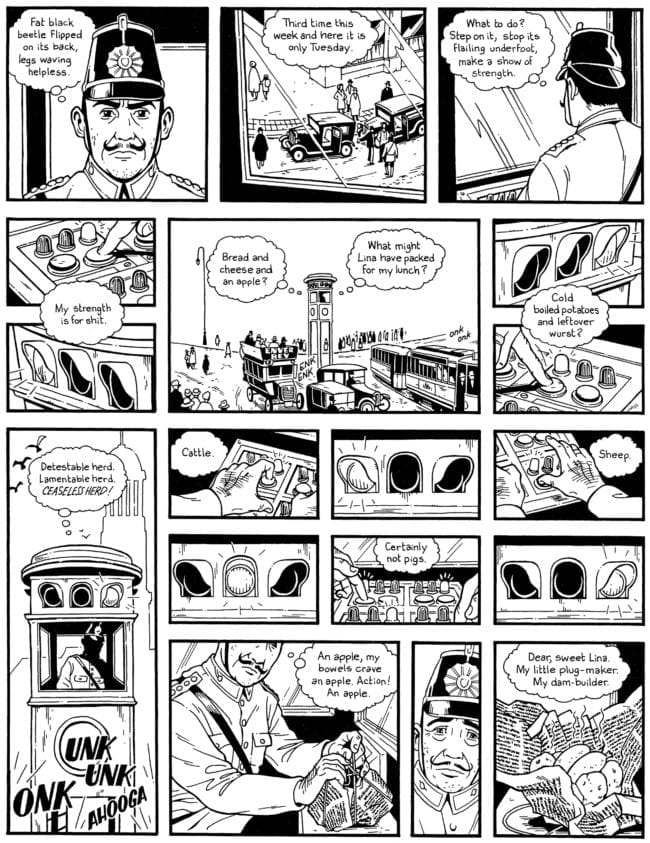

And then I got, you know, 24 pages in and thankfully, once I was in that story and I had these characters and I was paying attention to them as characters, those bigger ideas just kinda dropped away. And I was just dealing with the people. So any time I wrote a scene I would just imagine being each of the characters in that scene and imagine how they would interact with one another. And then I would look after I drew, I would look at the actual, physical space they were in. Sometimes that would trigger the next part of the story. Even though I was drawing everything and thinking of everything myself, I wanted it to be a kind of lively and active environment where I could pay attention to anything I wanted to. And in the beginning of the book there's this scene with a police officer in a traffic tower. The first traffic light in Europe. And that just came out of me actually drawing that. I drew that street scene and I drew that traffic tower and after I drew it I thought, "Well, who's in that?" So I had a little one-page digression where we go in there and pay attention to that guy and that couldn't have happened if I hadn't drawn the physical space and then considered my relationship to it or the relationship of the characters to it.

Yeah, I really like that idea, that these characters are just kind of doing their thing and you can kind of go visit with them for a while.

Yeah, I really like that idea, that these characters are just kind of doing their thing and you can kind of go visit with them for a while.

[Laughs] Well it very much comes out of my background with role-playing games too. Role-playing games were a huge part of my creative development. And that idea of inhabiting characters and not having a preset notion of what's going to happen in a given scene or story was influenced a lot by that.

Yeah. I know you've said before that each character has a life beyond the page, kind of what you were just talking about. And now that it's done, I wonder, do you sometimes, when you're just like washing the dishes or whatever, do you ever just like think about what happened to the characters after the book? [Jason laughs] Or is that something that you just refuse to engage with because that's not the focus?

I don't refuse to engage with it, but it does not come unbidden. My mind does not wander. I'm trying to think, yeah, no my mind does not really wander. The only time that's ever happened is with my first book Jar of Fools. There's a con man and his daughter who are two of the main characters and the book ends on sort of an open way where you don't really know what's going to happen. And I've imagined their fate. Those two particular characters. But elsewhere, whenever I've done a book... Yeah, that doesn't happen. When I'm doing a story their life definitely exists beyond the page and I think about them as more than what you see in the panel. But then when the story comes to an end I don't have any preconceived notion, even leaving aside preconceived notion, I don't even wonder. [laughs]

I am not making any decisions about that or drawing any conclusions myself. You know at the end of the story one of the characters has a particular, symbolic choice that's just given to one of the characters at the end of the story. And I realized when I decided to do that moment that I feel like that's the choice this character was confronted with and I'm not going to make that decision for him.

I knew at a certain point that I wanted to show this kind of full spectrum of human experience, I wanted the ending to be both tragic and somehow hopeful. I wanted that combination. And I did not know how I was going to accomplish that. But I held that feeling in my head up through the end and then it all sort of filtered down and came together to come up with that ending.

For one person working on one single fictional thing, 22 years is a really long time. Did you almost give up working on this thing?

There were times when it was hard. You know I went into it as a 28-year-old with all the energy in the world and committed to pay low rent and eat ramen while I lived in my studio apartment. And in that context I could draw at least 50 pages a year. I figured a page a week was probably reasonable, which is why I got the 14 year estimate originally. And then, you know, life has a way of getting bigger and more involved and you fall in love and you have kids and you end up having to get other jobs to pay the bills. And so the rate really slowed down and the pressure was magnified by the fact that I would get paid after I turned in a chapter. So there was no advance. It was, turn in one 24-page chapter and then get paid like seven months later. And I was never able to get ahead of that curve.

So there were times when I thought, "yeah, maybe I should stop this and go into video game development or you know just get like a regular office job [laughs] and make a decent living." There were times when the pressures of just trying to be someone who could who could lead a responsible and financially solvent adult life were powerful. And there were times when it was so hard to get stuff done that I felt distant and less energetic about the work itself.

But at the worst times, the three things that I thought of were: At that point I had an audience of some kind. So 200 pages in, it was all collected and put out as the first volume of the trilogy and I had people who were reading and I felt a responsibility for them. And then I felt a responsibility to the story itself, that it needed to conclude. And I think ultimately the biggest thing was like, if I had not completed it I would have felt personally really disappointed in myself. So there were dark times and then, you know, it was up and down. Like the whole middle third of the process was probably pretty up and down and then once the end kind of came in to sight I was able to kind of get more focused.

Thinking back to who you were at, 28, 29. If you knew then that you would be doing press for this book and it would be coming out when you're 50, do you think you still would have taken it on? Or do you think you would have done something else?

Thinking back to who you were at, 28, 29. If you knew then that you would be doing press for this book and it would be coming out when you're 50, do you think you still would have taken it on? Or do you think you would have done something else?

I think the nature of that decision that I described, that impulsive decision, is that there's no arguing against it. There's no rational, "Now is this the right...?" No, I would still do it for sure.

Yeah. When you're that age you also can't imagine what it's like to be 50 anyway.

[Laughs] You can't imagine what it's like to have two kids and four pigs and forty chickens. [Both laugh]

Wow, damn. I didn't know about all the chickens. That's a lot of chickens.

It's a lot of chickens.

Now that it is a book, now that you've got your phonebook, now that it is collected as an omnibus, was there a moment where you had to think about whether you would go back and change anything in the beginning? Or was it important to you to kind of preserve it more or less as it was serialized?

I did. I think when the first volume of the trilogy, when the first eight chapters were published, I went back and I redrew some early pages. Those same pages now, when I look back at them, look horrible to me. Because as you know, as a cartoonist, every page you draw you get better, and by the end of 600 pages you're going to be a different artist than you were at the beginning. A different artist and different human being. Especially if you've aged 20 years.

I think this urge towards perfection, which a lot of cartoonists have because a lot of us are pretty OCD, that urge is obviously a no-win battle because you would be constantly redrawing earlier pages if you fell into that trap. So at a certain point I just realized that you have to let things go. And like you said, stand as a record of that. That's who I was at that point as a writer.

Do you have a preference about how the book is shelved at a library or a bookstore? Is it supposed to be with historical fiction or is it supposed to be with comics?

I was just at a bookstore in San Anselmo, California, and I was delighted to discover that they've filed all of their comics according to the general category along with all the other books in the store. So all the fiction comics were in the fiction section. All the history comics were in the history section. I love that. And that's what I would prefer. I think the graphic novel section, or the comics section if you go to the kids part of the bookstore... I think a lot of people do like that stuff and they're in the mood for it. But comics is a not a genre. It's a medium. And I can see the need to shelve stuff that way from a marketing perspective. But I much prefer it shelved alongside everything else. That's where I would want my book shelved in, in fiction, or if there's the category of historical fiction then that's where I'd like it to be put.

You avoid using the swastika in Berlin, which is a really interesting choice. Talk about your use of symbols in the book.

So I avoided using a swastika because the symbol is so charged today. It was meaningful and powerful then because it was a symbol of the National Socialist Party and people had strong feelings about that one way or the other. So it was a powerful symbol then, but it did not have anywhere near the global power that it has today thanks to the Holocaust and World War II and all that. And I was interested in putting the reader there on the street in 1928, 1930, and having them as much as possible have the experience of somebody being a Berliner or being in the city at that time. And I think that when we bring all of our modern conceptions, or preconceptions, or received notions about a thing like the swastika into the story then it has much more weight than it would have to anybody then. So I just made this decision to leave it out.

There's still people walking around in Nazi uniforms and they're still carrying the flag but it's a white circle with nothing inside of it. And I was interested in seeing what would happen when you remove that symbol and it allows you to look more just at the people wearing those uniforms and their actions as opposed to just kind of make assumptions based on the flag that they're carrying. But what's really interesting is that people have read the book and then they'll find out, or they'll hear that there's no swastikas in it and then they'll swear that there are and they'll go back and try to find them.

I'm sure you're aware there is a large debate in fiction in general about whether you can as an author write characters and stories that are outside your own experience and whether that is cultural appropriation. How do you feel about that?

I'm sure you're aware there is a large debate in fiction in general about whether you can as an author write characters and stories that are outside your own experience and whether that is cultural appropriation. How do you feel about that?

When you talk about appropriation, inherent in that charge is the idea that I'm using it to my own ends, like trying to capitalize on it or try to exploit it somehow. And maybe it comes partly out of your approach to the subject. And I think that my approach to this subject was one of open interest and attempt to understand. When you're somebody who writes, or in the case of comics, writes and draws, the experiences of people, if I just wrote about my own experience it would just be another straight white guy's experience and that, frankly, is the last thing I want to read anymore. I'm much more interested in the experiences of people other than my kind of person.

Whether any given case or instance is appropriation, or completely unjustified, or however you want to spin it, I think that must come down to the individual case. And I'm perfectly willing to accept that some people will probably feel that way about any aspect of my work. And I will listen. That's the thing. I'm not going to get defensive and say, "oh, no, no, no, I have the artist's prerogative. I can do whatever they want." I'm gonna listen and pay attention to anybody that objects and evaluate that. And maybe that'll impact future decisions that I make. But I'm not going to just write stories from my perspective because that's a boring perspective. [Both laugh]

Yeah, yeah. And it sounds like you're approaching it with humility, which is key.

Yeah, I hope so. I hope that humility of is part of that. So my next book, this Western I'm talking about, the main character is going to be a 16-year-old Mexican girl. So you know that's as far from my experience as you could imagine it being, and it's 1865. So that's going to pose its own challenges and I'm going to do the best job I can and consult with people to get some feedback on that. But that's what I'm interested in, the stories of other people. Stories of people who are different from me.

It's so funny in comics, because we're talking about actual representation. Like, how you draw somebody is not taking a photograph or making a movie, it's how you're drawing somebody. What physical features are you emphasizing or to what degree do you pay attention to x, y, or z factor? And if any one of those feels like too much or exaggerated then yeah, you're opening yourself up. It's a really interesting kind challenge of subtlety I think.

In terms of Berlin, I know in the last couple of years at least, leading up to this moment, you've kind of avoided direct comparisons to U.S. politics, right? But, has that changed? [Jason laughs] I guess another way of asking that would be just, what is your day-to-day experience of the news?

Abject horror. [Laughs] So it's exactly, it's precisely the same aspect — the worst aspects of human nature that are being marshalled and organized. Stuff that's been simmering just below the surface is being brought out into the light and people are rising to that. And then there are specific things that are being done at a policy level. I'm pretty convinced that Steven Miller, he's read all of Goebbels' stuff. A lot of his stuff is right out of the playbook of how to talk about non-white people: how to tackle certain issues, the villainization of the other. All that stuff is drawn directly from the propaganda of that time and that's pretty clear.

So the basic forces at work are precisely the same. I think what's different beyond those forces are the specifics of our situation, which are: we're a vast nation, like vast, compared to the homogenous culture of Germany in 1933 or whatever. We're incredibly diverse as a nation. The last attempt to “unite the right” ended up with, I don't know, what, two dozen people walking the streets?

Yeah. Can I just say also that that was the same day that I was finishing the book. [Jason laughs] I was sitting here, in my living room in Washington D.C. reading Nazis coming to power, drawn very vividly. And it's literally two or three miles away.

That's crazy, wow.

It's unprecedented. I mean, it's unprecedented in so many ways, right? I feel like that the global forces are different. The technology is different. I couldn't predict what's going to happen in the long run. We can sort of project and imagine based on what has happened in the past. But the contributing factors are so various and complicated, so much more so, that it's impossible to know. So I'm just in a state now where I check the news and shake my head and pray for the future. Pray that my kids and people who are different from me can find happiness and peace in this world. [Laughs]

Yeah. Wow, sorry for dragging it down here but I feel like, you know, you wrote a book about Nazis and it's 2018.

Yeah. Wow, sorry for dragging it down here but I feel like, you know, you wrote a book about Nazis and it's 2018.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

This book, if it has a lesson, is the lesson how to empathize with people who are heading toward something horrible?

If I had to communicate one thing to people, it would be to have empathy. That would be it. To consider another person's experience and why they make the decisions they make. And that's one of the reasons I wrote the book, to say, "why did these people make the decisions that they made?" So yeah, if there was one thing I would hope to get across it'd be, you know especially in this day and age where — it's a cliche now — the fact that social media and screens have basically distanced us even further from one another. Actual face-to-face human connection and contact is the most valuable, precious thing that we have. And I kind of think it's the only hope. Otherwise it's all it's all just a bloodbath, right? It's all post-apocalyptic scrounging for resources and you know, defending your family with a shotgun. Not something I wanna do.

And I don't think it's going to look as cool as Mad Max: Fury Road.

[Laughs] Definitely not gonna look as cool.

You talked about your new book. Between that, and teaching, and your kids and your life and everything, now the Berlin is over, do you feel like you have a Berlin-sized hole in your life and how are you filling it?

Definitely no hole. It was nothing but an incredible relief to draw that last page. I just felt light in every way. And you know I've had 20 years to think about what other kinds of stories I want to tell and I have literally close to 100. [Both laugh] And of those stories I've settled on three that I hope to make my next three books and each one of them is going to be 96 pages long.

You know, maybe that will change when I get within sight of the end. But that's the basic plan. And each one will be self-contained and each one will be a straightforward genre piece but I'll try to play with the genre. Berlin is a very sprawling, meandering novelistic narrative. And I'm interested in exploring traditional three-act structure and seeing what I can do with that.