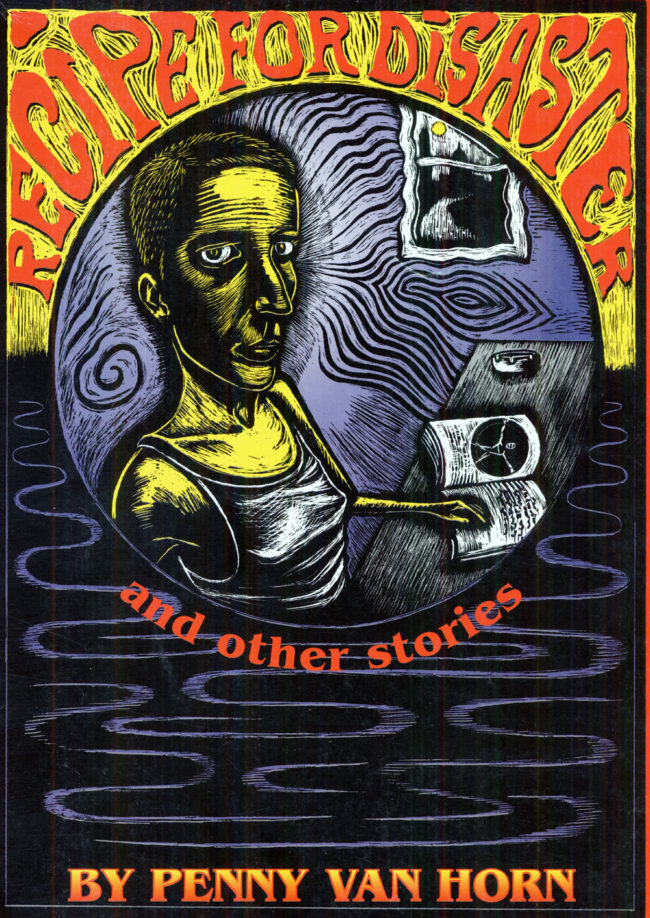

In the late ’80s, Penny Van Horn seemingly came out the gate already full-formed, with blistering short stories for anthologies like Weirdo, Zero Zero, Wimmen’s Comix, and the impeccable Twisted Sisters. To accompany her often visceral tales of slice-of-life suburbia, Van Horn used scratchboard to illuminate all shades of distressing human behavior in stark black and white. And then just like that, due to motherhood, animation, life, Van Horn departed alternative comics, leaving behind a small library of singularly hilarious and relentless short stories (collected in Fantagraphics’ 1998 Recipe of Disaster) and a more buoyant comic strip that has rarely been seen by anyone outside Austin locals.

Able to capture the range of human experience, both extravagant and infinitesimal, painful and exhilarating, often in the matter of just a handful of panels, comics have been made better by the intense energy Penny Van Horn has been able to tap into. We talked over the phone about her life and art.

Let’s start at the beginning. You grew up in New York, right?

Yeah, I’m from Rye, New York.

Where is Rye located?

It’s kind of a bedroom community of Manhattan. You could take the commuter train in and it would take about forty minutes to get to Manhattan. Really nice.

Did you grow up coming into the city and exploring?

My Mom took me into the city when I was about 5 or something. Later on, I worked there and lived there in the late ’70s, early ’80s. That was all in Manhattan.

What was your family like? Did you have siblings?

I had a brother who was eight years older, but that’s about it. Just a normal family life.

What did your parents do?

My father worked for the McGraw-Hill Publishing Company as a marketing director for engineering textbooks. He was there for about thirty-five years. He worked in one of those skyscrapers. It was kind of like a Mad Men scenario, I imagine, with people smoking and drinking in the office and whatnot.

Did you ever get to visit?

Yeah. They had their own building, The McGraw Hill building. They moved into another one right next to the Time-Life tower on the Avenue of the Americas. It was pretty swanky.

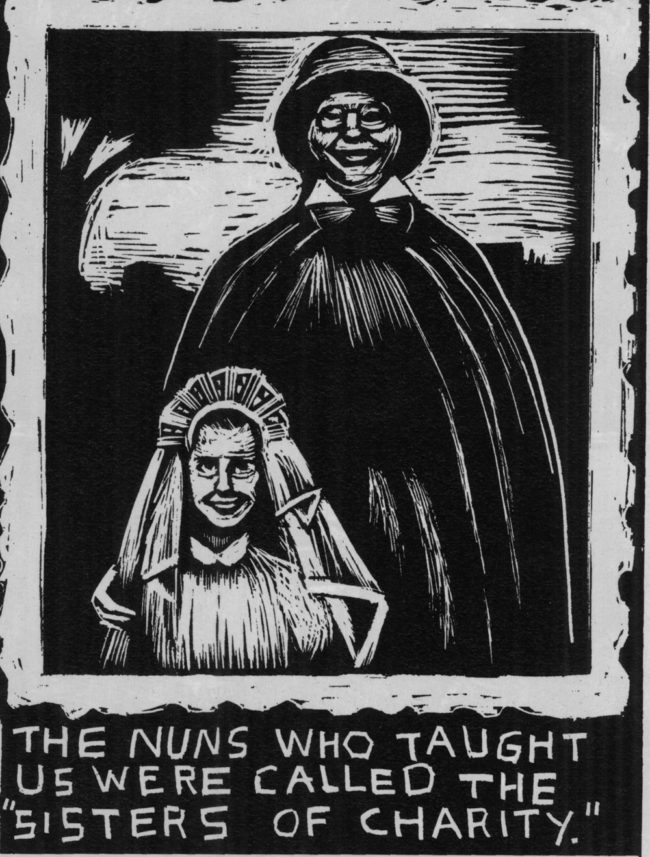

I’ve read in your comics that you grew up going to Catholic school.

Oh, yes. A defining feature in the shaping of my life.

How so?

I guess there’s an awful lot of guilt involved with Catholics. I’m not sure why. Some of the nuns were real sweet, but others were tough. “You sinned! You’re guilty!” And you’re like 5 years old saying, “Huh?” [Casey laughs.] “I’m just at school.” There were nice ones though and I’m kind of glad now to have had a religious background of any sort. It gives you a starting point for exploring everything religious and spiritual, whether you agree with it or not.

Is that important to you?

I’m not a practicing Catholic. I work for a non-profit which helps the blind and physically handicapped. It’s a call center and I help the callers. One of our patrons recently phoned and her name was Sister Maura or something. I said, “Oh, what denomination are you?” She said, “Actually, I’m an independent hermitress.” So I’ve decided I’ll go with that! I said, “Me too! Amen, sister.” [Laughter.] I still enjoy studying religion and all that stuff. Sometimes the interest fades out, but other times it gets more intense at different points in my life.

Where did your interest in art begin?

I’ve just always liked it. I was praised when I did drawings. Adults were like, “Oh, look at her. She can draw.” My dad always bought me comic books and coloring books. I would copy out of those. There were also the usual hand turkeys and other things you would make as a kid. I guess I’ve always had a vocation.

What kind of comics did your dad bring home?

The ones I remember most are Little Lulu, which is kind of old, I know. Richie Rich, Dot, Mad magazine. There were so many. Nancy, Dennis the Menace, things like that.

Did those inspire you to draw comics at that time?

No, not really. I would just do the art assignments at school and occasionally draw up in my room. We didn’t have the internet, as you know, so I was always just kind of kicking around and looking for something to do. You remember what that was like, hopefully. [Laughter.]

I’m 32, so there was a gap in my childhood without the internet.

Well, I’m going to be 65 this year.

You continued to dabble in art from elementary school on through high school?

I had a lot of encouragement from my high school teachers. They were great. I majored in art in high school.

Your high school had a program like that where you could major in something?

It was such a cool high school. It was in Westchester County and they had a Humanities Program. Rye High was a really nice school. They taught us all about art around the world and had us trying different things through the program. They wanted us to be exposed to different cultures and ideas.

Was it like a college prep school?

Not really. Our school was just unusual and pretty liberal, I guess. It was the ’70s, after all. I graduated in ’72. When was Woodstock?

1969.

Things were just headed in that direction. They let us go outside and draw in nature and all sorts of stuff. I guess we were “flower children.”

Did that program make your transition easier when you decided to go the art route in college?

I wish I had taken my dad’s advice.

Which was?

He wanted me to stay in our community, but I think I just needed to get away from home. Try something different.

Where did you go?

Well, actually, at first I wasn’t going to go to college. I was going to “live off the land.”

I had a serious attitude problem, I guess. I decided that I wasn’t going to school at all. He was freaking out, of course. My dad was a Franciscan brother who dropped out of the order, to make matters even more interesting. He pretty much filled out the application for me for the College of New Rochelle. It was a beautiful all-girls Catholic college and I loved going there, but I left. I went on a tour with my then-boyfriend driving around the Northeast. He had been at Cornell University but dropped out. Everybody’s parents were freaking out because we weren’t at college. We ended up at the University of Maine at Presque Isle, of all places. We just found that to be a cozy community and of course we got in. They were like, “Sure, we’ll take your out-of-state tuition.” My dad liked to visit, too. It was a potato farming town and right next to Canada. The winters were pretty brutal.

What was the art program like there?

I had a cool teacher and he still teaches up there. I’m still in contact with him. It was small. There was one big room that had everything: printing, pottery, painting. I enjoyed it. I felt like a big fish in a small pond. It was intimate and the teachers were good.

When did you start using scratchboard?

I had moved to New York City after college and had a friend who worked for Rolling Stone. She was an art director and illustrator, and she used it. I was just doing watercolor paintings at that time and looking for a job. It was fun to paint Manhattan because there are so many squares and angles.

About what year was this?

I moved to New York, I want to say in ’77 or ’78. My friend Kandy with a K suggested I try it. She said, “Here, try scratchboard.” It’s really double the work, you know? I would trace my drawing and use white carbon paper to trace onto the black clay-coated board, and then remove black as needed. I didn’t do it without a sketch first. It’s an incredible amount of work and I don’t know why I chose that medium. It just seemed to work for me.

Did you find that you had a talent or an affinity for it right off the bat?

I’ll put it this way: It makes everything look a whole lot better than if you just drew it. It’s much like woodblock printing. I really liked to do linoleum and woodblock as well, especially when I moved to Texas. I met a bunch of people who were from Texas when I lived in Manhattan. I hung around with them for a few years and that’s what led me here today. I was like, “Can you guys ever stop talking about Texas for one second?” [Laughter.] Then they decided they all wanted to come back to Austin.

When did you move to Texas?

I want to say ’84.

You moved with a group of people?

Just one person. A couple of others followed us.

What part of Texas?

I’m in Austin. I’ve stayed here ever since. My time in New York was pretty exciting and there were a lot of art personalities around and a lot of good bands. You could go see the Talking Heads in Central Park. I would see the B-52s and the Specials on the pier. I liked my time there a whole lot, but it was too urban for me.

That’s why you left?

I took a trip here with my boyfriend, and when I saw how pretty Lake Travis was… It’s like a quarry with white rocks and blue-green, clear water. It was so pretty and I like to swim. I fell in love with the lake.

In your biography in Twisted Sisters, it says you first saw comics aimed at adults in National Lampoon.

It might have been in High Times even before that. There was a little corner store and I liked to go in and look through the magazines for comics. I got struck by some of those. It was Ron Hauge’s Modern Problems in National Lampoon that I remember the most. It was so starkly black and white. There was something about it that made me want to do comics.

That was the catalyst?

I did start making comics shortly after I saw those, but I don’t remember why. I’m not sure what started me down that path and I can’t remember my first comic either, except for the ones on notebook paper in junior high. I read Weirdo and starting writing to them. I saw more pop-art in comics and thought I might be able to get in on this. I could do that.

In an issue of Weirdo in 1985, you got second place in an “Ugly Art Contest.”

Yes. [Laughs.] Another high point of my life.

Was that your first time being published?

I had some illustrations when I lived in New York published in a few places, some random things here and there. But that was the first time I tried to do comics. Before that it was all illustrations for magazines and paste-up work when they still used wax and rubber cement and thinner.

You were doing production work with X-acto knives and stuff like that?

Yeah. That made me think in squares and angles a whole lot. You get in the mindset that you want to put things in boxes and move them around.

Did you receive those rewards that you were promised for winning second place in Weirdo?

Yes, I did. I still have the album and I know every song on it. I also got a rock art set. I made some art out of that, but not quite the way it was supposed to be used.

Did that lead to you starting to submit to Weirdo?

I think so. Somewhere in the back pages of all that I think Aline Crumb was trying to get in touch with me. She wanted me to be in a women’s art issue. It’s a little hazy in my mind.

Pete Bagge was editing when you started to appear more regularly. Did he reach out to you?

I can’t remember. I was working then, so I had to split my time. I was working at the University of Texas as a receptionist for about six years before I had my beautiful baby girl. I would sometimes do paste-up and layouts after work too, so I didn’t always have a ton of time. I would fit comics in where I could.

Having a child I’m sure made your time even more difficult to manage.

I did comics again, but not until she was about a couple of years old. I could bring her to a sitter so I could work for a few hours or when she went to nursery school. That’s when I would focus on comics.

How did you get involved in Wimmen’s Comix and Twisted Sisters after Weirdo?

I guess people contacted me, as far as I can remember.

Your first Wimmen’s Comix appearance was in an issue that Phoebe Gloeckner was editing.

You’ve done way more research than me. [Laughter.]

Was that an exciting time? I’m speculating here, but it seems that during that period there were more women making comics than any time previously in history.

It was fun. The only thing is I got the feeling that people were saying, “They’re just publishing them because they’re women. They’re pretty good for comics made my women.” Do you know what I mean? It’s not a great attitude, but I remember feeling that.

The contributions were marginalized.

A little bit. I just did my thing, though.

The Twisted Sisters anthologies are incredible. Some of the best comics ever created, in my opinion.

They are pretty cool. I’m proud to be a part of them.

Do you ever look back at your older work?

Sometimes I flip through them, like if someone is coming over to see my studio and they are glancing at them. But, honestly, I haven’t reflected too much on them. There are so many things I want to do still. I’m usually trying to look forward rather than back.

You’ve always done shorter work. The max has been about twenty or thirty pages, but most of your comics are much shorter than that. Have you always been attracted to brevity and that method of storytelling?

Like I said earlier, my comics were very time consuming because I was using scratchboard. It takes twice the amount of time, I think. That’s just all I had time for, and I could get a story told quicker. Sometimes I wish I had just written the stories like a novel and had random illustrations. I think the stories would have come off better. That’s what I would do if I could do it over again. I think I write as well as I draw and I could have fleshed it out more.

Your art career would have been different if you chose that route.

Sure. Everybody’s just kind of winging it, you know? If somebody asked me to do something back then, I would do it. I wasn’t planning on doing comics as a career. I wanted to be a painter and work in color. I wanted to do big, wall-size paintings and stuff. I think I got tired of working in small, black-and-white squares after a while. I wanted to move on. I continued to do comic strips for the Austin American-Statesman and illustrations for the Austin Chronicle. I had some full-page comics there too. You probably haven’t seen those that appeared in the newspapers. I lost all my scans when my hard drive crashed, so most of my work doesn’t appear online. I have hundreds of 4” x 5” comics that I only have the originals of. Send me an intern, would you? Someone who’s 20 years old and knows how to work a scanner. [Laughter.]

Wow, at least you have the originals.

That newspaper work continued after all my anthology comics stopped. At that point I just wanted to have use of my hands and not be scratching away eight-hundred-thousand marks.

Circling back to the length of your stories, I can’t imagine some of them going any longer because of how dark and intense they get. A few pages is often good enough.

You know how very graphic Recipe for Disaster is and what a tell-all it is. I kind of try to keep that under wraps a little bit. I must appear somewhat crazy to many people. I’m used to it, but I do fear somebody reading that and saying, “Jeez,” you know? “Go back under your rock.”

Has that raw truth-telling always been compulsive, or at least a part of your personality?

I guess so, apparently.

There’s a lot of vulnerability there, too.

People often say things like, “Look how brave you are.” I’m like, “Oh, please. More like how embarrassed I am.” I put it all out there and I guess I had something to say.

Were you nervous before you published stories like “Psycho Drifter” or “Molested?”

No, no. Those are both about men being stupid. I’m talking about the title story in Recipe for Disaster basically.

The first main story there.

Yeah.

Can we discuss it?

I don’t want to dwell on it too much, but yes.

In that story you read a lot of psychology books, take LSD, and sort of have a break from reality.

Right. I think it started as a religious experience. It was like one of the stories where people go, “Eureka!” or “I get it.” It started out that way for me, but then I wasn’t able to handle it given some things that had happened in my life. My ego identified with the self and I got kind of megalomaniacal. I had some rough times. My mom died. Maybe I was just too young. Maybe doing yoga is just too dangerous because it can spark something that you’re not ready to handle.

You think you can open yourself up too much?

Yeah… I’ve had these things happen to me over and over again, these spiritual reawakenings. All of sudden, nobody knows what you are talking about or they become really guarded. “Why are we talking about this now?” You want to talk about religion and people want to keep that under wraps. You can’t live in a normal society talking like that. Those memories and those thoughts get eroded like water washing over a sand castle. It goes away and comes back again and again. It’s complicated.

You mention that this has happened to you a few times. How were you able to handle it differently than what takes place in “Recipe for Disaster”?

I’m certainly not going to buy the farm a second time. [Laughter.]

You can manage it now?

It still gets hard for people around me. “Why are we talking about the Bible all of a sudden? Since when do you sit around watching videos of hot swamis?” Some people are really receptive and others are like, “Can we talk about something normal?”

When I read that story, I get scared of the loss of control.

Have you had that kind of experience?

Not at all, but I’m kind of a Midwestern control freak. I don’t let myself get too out there because I’m afraid of what would happen.

I think that’s where being an “independent hermitress” comes into play. I have a whole cosmic consciousness library I’ve had since I was in my early 20s. I go back to it and start ripping books off the shelf every few years. The older I get, the more I want to really think about this and ponder it. I guess you just have to live a certain type of life.

Your age influences that cosmic openness?

I have more time for introspection, if I retire, especially. I’m working toward that. I want to do more writing and more painting. I want to pack my things and sell my house and move someplace more affordable. I’ll have time for thinking. I guess I have more work to do, but I’m waiting to see what that might be. Having a full-time job doesn’t leave a whole lot of time for much else. Luckily, I have a job I like and am proud to have.

In that same story, you go up to a bank teller and demand money. Do you remember that portion?

Yes.

How did that go?

Well, here’s where I don’t like talking about just how crazy I was. It’s a bit lurid for me. The bank tellers just looked at each other like I was crazy, which, you know, I was.

Some of that way of thinking reminds me of that book The Secret. Are you familiar?

Oh yes, by Rhonda Byrne.

That part of your story reminded me of what I know about The Secret — thinking things into reality or believing something until it manifests itself.

Patti Smith’s song “Free Money” might have had something to do with that. I think I was just going about everything the wrong way. I also remember calling the producer of Sesame Street and saying, “I’m receiving your messages and want to be part of the show.” They said, “You can apply to be a producer, but you’re going to have to write some content.” I remember thinking I could get a grant, but I ended up short-circuiting before that really happened. I guess I was expecting quicker results.

There’s the fine line between what you call short-circuiting and the ambitious strategy of believing something into existence.

I was just watching something about that yesterday. We have downtime at work and sometimes I watch videos. It was the same idea: First, you go around operating by society’s rules, then you realize that there’s some wriggle room. Then you have to try to pull yourself together and get aligned with whatever forces to make things happen. But you have to be open to receiving some kind of incoming material from your source, or the ground, or God, or whatever it is. It’s a process you really have to work on. Then you get energy, grace, or whatever. That’s the video I was watching and I guess it’s the same idea. Apparently, I was expecting results to come way, way too quickly. Now I understand it. You just have to have a lot of patience with these things.

Did becoming a mother change this way of thinking or your art at all?

You haven’t seen the million comics I produced for the newspaper that were based on my family life. My poor daughter has been featured in many of those weekly comics. She still scolds me when she looks back at them. [Laughter.] She at least laughs at them now. Her friends would say, “Saw you in the paper again,” and she wouldn’t like that in elementary school, but now she thinks they are funny. The poor thing.

How did a weekly strip come about?

I think I went to them and asked them if I could do it, as far as I remember. There was a new section of the paper and had things like Too Much Coffee Man and stuff like that. I went, “I could do that.” That was back when the Austin American-Statesmen still had a building on the river. Now our paper is printed in San Antonio and it’s a day late and a dollar short. But they had an exciting new section called “XL-Ent,” which was a super large entertainment section. I got a lot of positive feedback. When I was swimming at the Y or in the hot tub, people would ask things like, “What do you do?” I would say, “I’m a cartoonist,” and they would know the strip. The strip had a different title every week, for example, “Pecan Tassel Torment.”

I know a lot of cartoonists who are hesitant to talk about what they do when asked things like that.

Not me. I tend to see people as caricatures and their personality exaggerated. I like to look at things around me satirically. I have sort of become a stand-up comedian at work. I just perform it instead of drawing it these days.

When you were doing comics for the newspaper was it difficult to tone down the subject matter? You were doing those intense, personal stories that made up Recipe for Disaster and then had to focus more on observational humor.

No, it was great. It’s easy. Stories like “Recipe for Disaster” are the hard ones. Diane Noomin encouraged me to do that. We were going to have another compendium and that was going to be featured in it, but it fell through. So I just made the personal anthology with Fantagraphics. But I was relieved to be doing more lighthearted things. I need to put together a collection of those. Maybe Fantagraphics would like to do one now. I have at least 100 strips. There are some about Austin and how stupider it got the larger it grew. There are some political ones. Some family ones.

I’m sure there’s been a lot of change in Austin since you moved there in the ’80s.

It’s gotten to be a metropolis and it has lost all its character. People are always complaining about it. All the nice swimming holes are so mobbed with young hipsters that I can’t even go. People were already thinking Austin was getting too big even when I moved here. The flavor of it is ruined. They will bulldoze my house when I sell it and just scrape it away. I have a nice house built in 1938, but I know it won’t last.

They’ll make an obnoxious apartment building.

I have a big enough plot that it will probably be a couple of condos.

That seems to be happening in all larger cities right now. I don’t know where people are all going to live after they can’t afford these condos anywhere.

I’ve been wondering the same thing. Things are starting to get ugly. Climate change and all these huge storms.

Politics seems to be interesting in your state right now. People are keeping an eye on Texas races and the possibility of flipping the state in the 2020 election.

Oh, I just love being in a red state. It’s been soooo great. I hope that we’re turning the state bluer. We’re trying. The next generation will be the deciding factor.

In 2002, you did some strips for The Comics Journal Special Edition. One was “White Noise” and the other was about birds. Do you recall those?

Of course.

Those look completely unrecognizable from your previous works.

I was working for Bob Sabiston at the time. I had worked on the movie Waking Life and some other animation projects for him. I was using his program to do those pages. It was his system of interpolation animation, but you can do still work in it too. That’s how I made those.

How did it feel to use that bright of a color palette and to make things look more digitally rendered than scratchboarded?

I liked it. I was tired of scratchboard and could never master Photoshop enough to do it there. I did like to use Kid Pix on the computer, where you could just draw a circle then fill it in. I lost that program in the hard drive crash too. I’m always working a job somewhere, but the more free time I have I do tons of different art. It’s all just about finding spare time. I liked doing those pages, but I didn’t want to keep it as my style forever.

Let’s talk about your time in animation. You mentioned that you worked on Waking Life. Did that result from an Austin connection with Linklater?

Yes, a friend told me that there was a local job where you could get paid to animate. I had been working office temp jobs. I got hired by Bob for that movie then did more work for him, personal pieces like one called “Grasshopper.” He’s fun to work for.

What was your experience like on Waking Life? I remember the hype when it came out and how it was touted as a groundbreaker in terms of animation.

It was great. I sat in a room with a bunch of people drawing. You had to draw the same line over and over, but move it a little bit every few frames. I met a lot of cool people and I enjoyed it very much.

What did you think of that movie when it came out? I was in high school and it blew my mind, but I think it went completely over my head. [Laughter.]

It’s beautiful. It’s like a moving painting. It’s strange that I’m more known for working in black and white because I love color. I care so deeply about color. That movie was so liquid and so bright. I remember telling somebody that brushstrokes are like porn for me. [Casey laughs.] That’s the way I feel about painting when I get a chance to do it. I had a more recent show that was a lot of large color portraits.

You still try to find time to paint and create work?

Yeah. I don’t know how things go so busy in my life, but they have. I need to retire. I participated in the West Austin Studio Tour recently and I was with a couple people displaying work. It was time-consuming to drag all of my stuff over there. I did some silkscreen printing and brought some random art that I wanted to sell. That went pretty well. I sold a few pieces and enjoyed myself, but that whole thing took two weeks. There’s never enough time.

When you think back to all the comics you made, does any one story stand out as the one you’re most proud of?

That’s a good question. I was proud of “Ten Dollars for Two Minutes” because of how I structured it and how I drew the car in it.

Did that actually happen to you? Did that man die?

Yes, that really happened! They’re all true stories. I also liked the one that did where my friend said I made my ex said I made him look like he fell asleep on a waffle iron.

“Domestic Bliss.”

For some reason, I love those little squares I made for that story. My then-husband said, “Jeez, Penny. You made me look like a fat little owl in that story.” Which I replied, “Well…?” [Laughter.] It is kind of fun to torture people through comics. I once worked for a temp agency and it was a marketing thing. I didn’t do well, I guess, selling products. They wanted me to give this canned speech over the phone, like, “Working hard or hardly working?” I just wanted to talk normally. After all this training, they got me set up and I made one call before lunch. After lunch, I came back and my computer was turned off and my stuff was packed in a box. “You don’t have a job here anymore.” I laughed and thought, “OK, I’ll see you in the funny papers!”