The winners in the main categories at this year’s Angoulême festival raise interesting questions about French cartooning and satire. Christophe Blain and the pseudonymous Abel Lanzac took the Fauve in the category ‘Best Comic’ for the second volume of their political satire Quai d’Orsay, while the lifetime-achievement Grand Prix went to editorial cartoonist and occasional comics artist Willem.

Well, that’s not entirely accurate. The Grand Prix was actually split between Willem and Akira Toriyama, the creator of Dragon Ball. That way, the awarding body (the so-called Academy, which consists of past winners) could simultaneously assuage the doubts of its progressive voices, who attempted a grand reform of the Grand Prix this year—and for whom Toriyama, as the first Japanese recipient, represents a step forward—and its old guard, who would keep the power of choice entirely in their hands, and for whom Willem was the only familiar name on the newly-instated ballot from which they had to choose a recipient.

But I digress. Quai d’Orsay narrates the daily doings at the French foreign ministry as presided over by the outsize figure of Taillard de Vorms. It is told primarily from the viewpoint of a young aide learning the ropes who comes to admire his boss while suffering under his idiosyncrasies. It is clearly a roman à clef, so it came as little surprise when, at this year’s awards ceremony in Angoulême, it turned out that Lanzac was in reality diplomat Antonin Baudry, currently French Cultural Counsellor to the United States, and the comic a fictionalized chronicle of his time serving on staff for former French foreign minister Dominique de Villepin.

Ostensibly a comedy, Baudry and Blain overexert themselves trying to play Vorms’ redoubtable personality for laughs. In perpetual motion, he strides through cabinet rooms accompanied by loud VLON!s and VLAC!s as feet stomp, doors slam, and thick books (Heraclitus, Democritus, Ignatius of Loyola) are thrown open on tables in front of stupefied underlings. His capacious shoulders bop above his head and smoke puffs from his lapels as he recites his tripartite doctrine of management: Responsibility! – Unity! – Efficiency!, his arms chopping the air with the assurance of a master chef. At certain points of heightened rapture, he is even depicted as a Picasso-esque minotaur, his horned figure commanding the page in vigorous red. The presentation is so relentless that any element of ridicule, any incipient laugh, is smothered in fawning admiration of the great, erudite and conscientious (French)man behind the caricature. Representing him as Darth Vader preaching his doctrine to our young hero or kneeling to Emperor Chirac makes little difference—the tenor of the portrait is clearly heroic.

(And the work overall is romantic. Baudry’s stand-in is the kind of ruffled, three-day stubbled ingenue that will melt a woman’s heart; his long- but silently suffering and remarkably understanding girlfriend is slim, delicate, and smart, with jet black hair that always falls just right. This should make one suspicious right off the bat. OK, Blain genuinely seems unable to draw ugly people (a liability in satire) but even so—how much trust should we place in Baudry when he chooses to have ‘himself’ depicted like that?)

Anyway, the award-winning volume here under consideration is an account of the lead-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, as seen from the benches of the French mission to the UN. We get the whole sordid story of political maneuvering between the US and its allies in ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Europe, with Colin Powell’s infamous presentation of fabricated evidence to the UN Security Council on February 6 providing the set piece. The target is so worthy, one senses, that Baudry and Blain let panegyric occlude their satire. Their version of Dominique de Villepin’s justly admired address on February 14 plays out solemnly, the sole ‘comical’ element being a panel in which he appears as the fairly obscure Japanese TV character Space Sheriff Gavan (apparently commonly recognizable to Frenchmen who grew up in the eighties), but just like the Darth Vader analogy, it comes across as adulation sheathed in a shallow veneer of twinkly-eyed pop erudition, rather than commentary of genuine insight.

Blain is no doubt one of the most talented draftsmen in comics today, his line and color always exquisitely tasteful on the page. Eye candy. But he convinces less as a cartoonist. His facility seems to affect his panel-to-panel storytelling, in that it comes so easy that he never appears to think much about the choices he makes. It reads clearly enough, but the narration is gassy and distended—it seems as if he lets one panel follow the next without much premeditation, an easy overflow. This results in endless sequences of talking heads, with each panel showing only limited invention in terms of carrying the dialogue (some of which could easily have been cut in the first place). And although his dashing interpretation of de Villepin has iconic qualities, his limits as a caricaturist are revealed in his more true-to-life approximations of such central players as George W. Bush and Colin Powell, who are stilted and jarring in the company of their eloquently rendered co-stars.

Look, the French are justified in being proud of their government’s stand on the disastrous war in Iraq, but does it need any more vindication? Ultimately, Quai d’Orsay is little else than an attractive-looking stroke book for the French national ego. A cinch to get rave reviews, sell out print runs, and win the award for best comic at the biggest French comics festival, but hardly worth the attention of anyone genuinely interested in the politics it claims to lampoon.

Quai d’Orsay is emblematic of a certain current of political satire in France. One that elegantly employs ridicule as consolidation, driven by basic pride in the country’s storied institutions, despite their failings. It is fundamentally idealist, and I would guess it is the taste for this kind of commentary that has made the Danish TV show Borgen—which features a thoroughly Good prime minister wanting to Do the Right Thing—such a huge hit in France. (And in Denmark of course—another country that retains some faith in its institutions.) (It seems to me that if it were a British comic, it would be something more like Armando Ianucci’s The Thick of It).

Digressions out of the way, there is a flip side: A current of French political satire that is coarser than just about any other in Europe. The kind of balls-out mockery that does not shy away from depicting former president Sarkozy giving the Pope a blow job, with a number of dictators, including Bashar Al-Assad, Ghadaffi, and Putin waiting their turn; or a Muslim, who might just be the Prophet Muhammad (blessed be his name), shitting out a star while praying, accompanied by the caption “Muhammad: a star is born.”

The locus of this kind of humor has long been the bi-weekly Charlie Hebdo, the magazine which reprinted the infamous Danish Muhammad cartoons along with a slew of their own in 2006, adding no small amount of fuel to that particular fire, and which has since been testing that same boundary continuously, netting a volley of Molotov cocktails along the way. It is carried by a kind of insolence that one senses has been nurtured by Catholicism, and indeed one that never shies away from attacking the church.

One of the fathers of this style is Willem. A member of the Provo movement in his native Holland, he immigrated to Paris just in time for May '68. As a cartoonist he became a steady contributor to the legendary satirical magazine Hara-Kiri, from the ashes of which Charlie rose, when publication of the former was closed down by the government in 1970. Willem has drawn for Charlie ever since, even serving a stint as editor-in-chief in the seventies, but his primary platform has been the leftist daily Libération, where he started working in 1981 and remains today, one of the best recognizable graphic signatures of the French left.

Never a natural, Willem draws in a rough, angular style founded in naturalism and reliant on photo reference, albeit always skirting the grotesque. However, his loose contouring and heavily spotted blacks secure the expressive power demanded by the material. His limits as a caricaturist are offset by the force and clarity of his visual ideas, still following the principle, formulated by the editors at Hara-Kiri, that “a good drawing is like a punch in the face.” He is best when meanest—when doing illustration or reportage he is inevitably less effective than when in full satirical mode. Here, he can be blistering — almost scabrous in his attacks, using all means at his disposal: sex, violence, blood, feces! His is the kind of dark humor that aims to expose the hypocrisy, cynicism, and amorality of those who wield power, often by graphically depicting the human suffering they inflict.

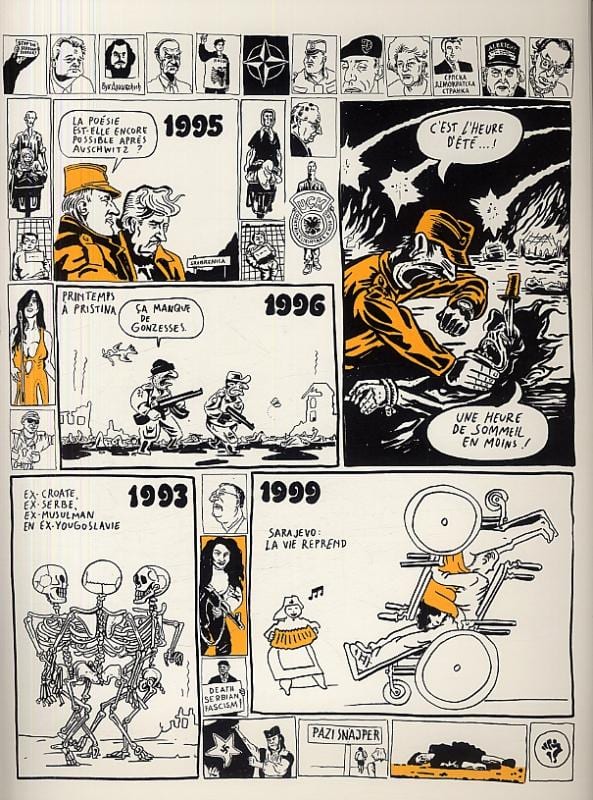

His latest book, Degeulasse—‘Disgusting’—released just in time for the Angoulême festival, is a case in point. Less overtly topical than his Libération and Charlie work, the book enables him to make a grander statement on our time, using comics, rather than standalone cartoons. The oversized, saddled-stitched softcover book is a panorama of world political history of the last thirty or so years, with plenty of references to earlier events providing context. Each page consists of a generous assemblage of cartoons, some larger than others, all on a single theme, such as Afghanistan or Israel-Palestine. The smaller ones are portraits of key players and anonymous individuals, as well as various relevant symbols and other imagery that helps set the scene or establish the tone, while the bigger ones tend to focus on or encapsulate events or situations and are occasionally marked by the year to which they refer. Certain images include dialogue in balloons, written in Willem’s signature stilted French. The general focus is on the abuse of power across the world, with various French prime ministers and American presidents, China’s and Russia’s leadership, African dictators and Islamic terrorists, all posited collectively as the scum of the Earth. Oh, and the Catholic Church, of course, is a strong presence, all for the bad.

Hitler says to the Pope, “One of us wasn’t democratically elected,” and the latter answers, “We don’t give a shit”; Helmut Kohl welcomes an East German breaking through the Berlin wall with an erect, peeled banana coming out of his pants; Radko Mladic says to Radovan Karadzic, “Is poetry possible after Auschwitz?”; Putin gets a handjob from an Islamic militant, saying, “Thank you Chechens”; Saddam Hussein assures his underlings that the Americans would not be so stupid as to invade; Bush explains to a crippled veteran “not to get our asses cooked in Iraq would send the wrong signal to terrorists, making them think America is weak”; Pope Benedict XVI exclaims, “Go forth and multiply” to a female skeleton pregnant with a baby skeleton standing under a ‘no condoms’ sign, while a bishop is getting blown by an altar boy behind him; Yasser Arafat and Ariel Sharon trample around in a circle of blood and bones following signs saying ‘PEACE’; an African leader presents a rape machine consisting of a massive wheel fitted with big metal dicks crushing women into the ground, explaining that mass rape is the only affordable means of war available to a poor country; an Islamic militant with a hack knife and an explosive harness holds a severed head Hamlet-style, asking, “Why don’t you understand anything about our culture?”; and so on.

It may seem a tad ham-fisted in the retelling—and it indeed is—but the dogged fury with which it is both conceived and executed is hard to deny. Willem has no time for subtlety. And while each self-contained image may be more or less effective, it is the mosaic they create that is key to the book’s power. By juxtaposition and accretion, he draws a horrifying portrait of the modern era that finds its logical, Goya-esque endpoint in two skeletons, standing on a heap of bones, hacking away at each other in the year 3000.

It seems somehow fitting that Baudry/Blain and Willem should be honored alongside each other this way, representing as they do opposed traditions of political commentary that are both distinctly French, and probably would not exist independently of each other. Each tradition is a manifestation of national pride born of enlightenment and revolution at the nexus of institutionalism and individualism.