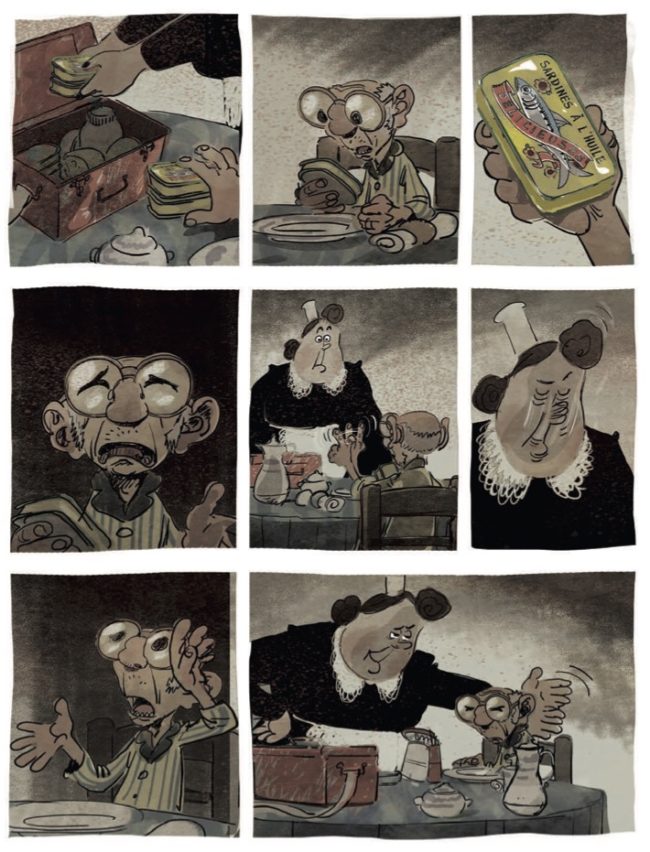

It’s a love story. And a story about sardines. But not about loving sardines. In fact, the fisherman in this salt water adventure hates sardines. Nevertheless, his devoted and devout wife packs tins of these piscine provisions for his lunch as he heads out to make a living on the briny. He tosses an unopened tin into the hold, adding to a rather stout stockpile. A high seas calamity sets the course for this fish tale, taking the fisherman, as well as his dedicated wife, half-way around the world, where she meets fame, and...imprisonment...in her quest to find him. But what they really want most is each other.

It’s a love story. And a story about sardines. But not about loving sardines. In fact, the fisherman in this salt water adventure hates sardines. Nevertheless, his devoted and devout wife packs tins of these piscine provisions for his lunch as he heads out to make a living on the briny. He tosses an unopened tin into the hold, adding to a rather stout stockpile. A high seas calamity sets the course for this fish tale, taking the fisherman, as well as his dedicated wife, half-way around the world, where she meets fame, and...imprisonment...in her quest to find him. But what they really want most is each other.

A Sea of Love was written by Wilfrid Lupano, and illustrated by Grégory

Panaccione. The book is wordless, except for a few instances of environmental print, which appear in English in the U.S. edition. It was originally published in 2014 as Un Océan d’amour by Editions Delcourt. I read the 2018 Lion Forge (U.S.) edition, which I received as a review copy. This book is currently an Eisner Award triple threat. It has been nominated for a 2019 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award in three categories: a “Best U.S. Edition of International Material;” a “Best Publication Design;” and the illustrator, Grégory Panaccione, has been nominated for “Best Painter/Multimedia Artist (interior art).”

In late June of 2019 I met up with Wilfrid Lupano in Washington, D.C. at an event connected with the American Library Association annual conference, and we had a conversation that navigated throughout his creative process for the book. Here I follow up with him in an intercontinental email exchange in early July of 2019 about this maritime masterpiece (he’s now in France, and I’m not).

Brenda Dales: You shared with me that you wrote text for A Sea of Love, but it sat in a drawer for three years before it was illustrated and published. Can you tell a little more about how the story you wrote evolved into a wordless book (also called a silent book)?

Brenda Dales: You shared with me that you wrote text for A Sea of Love, but it sat in a drawer for three years before it was illustrated and published. Can you tell a little more about how the story you wrote evolved into a wordless book (also called a silent book)?

Wilfrid Lupano: It was actually an exercise, for me. I wanted to challenge myself on a wordless story to force myself to write differently. I use dialogue a lot in my work, so it was for me a big step. To develop a storyline without words, you have to think differently. Classical narrative techniques won’t work. So it’s a good exercise to improve one’s narrative skills. As it was only like an exercise to me at the beginning, I felt totally free to write the weirdest thing ever, I had no concerns about an “audience,” or what publishers would think about it. I just wrote what was on my mind. And, in the end, I thought the story was very “unusual,” maybe a little bit too weird to seduce the publishers. So I didn’t really dare to send it to them, and it remained in my drawer for about three years. I had to experience some success with some other books before I was confident enough to reveal my strange mute story about love and sardines.

You explained Grégory Panaccione completed the illustrations in a somewhat short amount of time. What was the creative process like between the two of you? For example, how often did you communicate, and did the illustrations imply any plot differences?

Usually, my scripts are written page by page. Not frame by frame, because I don’t like to do that. I think the frame by frame narrative building is really the artist’s privilege. But I write page by page, as a guideline. Though, for A Sea of Love, I didn’t want to narrow Grégory’s creativity with any kind of frame. So before I sent him my text, I deleted any pagination marks, so he could read it as a kind of short story. This way, he was able to imagine his own narrative rhythm. His first storyboard was around 180 pages. But we worked together on it, submitting our work several times to some “panel readers” who hadn’t read the original script, just to see if they could understand the whole thing just through the images. From their feedback, we upgraded the storyboard, which went from 180 pages to some 225. Greg did the whole book in six months, which is totally crazy. He’s one of the fastest artists on Earth, I think. Greg lives in Milan, Italy, and I live in the southwest of France, so we didn’t meet much during the creative process. Fortunately, there’s Skype, emails, and we did a couple of work sessions at our publisher’s place in Paris. We really spent time together once the book was over, when it was now time to go to festivals and bookstores to defend it.

This book became a personal favorite the first time I “read” it, but I missed much. When you explained the tale begins and ends in Brittany, it gave me an entirely new way of meaning-making. As a reader in the U.S. I did not immediately associate the book with Brittany, but knowing the setting and cultural aspects opened doors and added much to the story for me. Who were your intended readers, and would you have written anything differently if you had known it would be published outside of France?

As I said before, I had no intended readers at the beginning, because it was an exercise for me. And it’s probably impossible to write this sort of story thinking of a specific audience. There is clearly no specific audience for stories about old fishermen from Brittany looking for love on a polluted ocean. Or maybe just everybody is the intended audience for it. I don’t know. Anyway, Brittany has a few folkloric clichés that I wanted to integrate in my story, but not just as “background” elements, I wanted them to be part of the plot. These folkloric clichés are, for instance, the “bigouden” women’s hats, sardine cans, crepes, traditional fishing, a certain degree of bigotry, or a specific dance called the “gavotte.” All of these elements are part of the story, almost like characters. I used them to twist the storyline several times.

Because the story begins and ends in the small cottage of the fisherman and his wife, it comes full circle, and immediately reminded me--as well as some others I learned--of the Grimm Brothers tale “The Fisherman and the Sea,” where the wife gained riches and power but she is eventually satisfied with the unassuming surroundings she had in the beginning. The wife is not greedy in your tale and her goals are different than in the Grimms’ tale, but are there influences of any traditional tales in A Sea of Love, or what are the influences?

I was more influenced by Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, and also by Homer’s Odyssey. To me, my little fisherman is like Ulysses trying to sail home, and going through many adventures on the way. But as a counterpoint of Ulysses’ wife Penelope, I didn’t want my female character to wait for her husband to come back, weaving endlessly. She’s the one who gets out of her comfort zone to go home to search for him, though she never left her village before. She’s an adventurer.

In a desperate attempt to figure out how to find her husband after a fortune teller reveals an image of Che Guevara in a pancake (crepe), the wife prays on her knees to a statue, which is assumed to be the Virgin Mary, until she wears holes in her tights. Is this “Our Lady of Eternal Aid” in Querrien?

Not really . . . it’s an allusion to the traditional importance given to the Virgin Mary and to religion in general in Brittany, as it is often the case in traditional fishing culture. When the boats are away, there’s nothing left to do but praying. In France, we have many “calvaries” often situated in heights so that you have to commit really to reach them. My grandmother, who was from Brittany, used to take us, my brother and I, on those calvary roads sometimes. In my story, “Madame” doesn’t know what to do to find her husband, she’s begging for and advice, a sign, something . . . that’s why she goes there. And the sign actually pops up! Unless it is purely random . . .

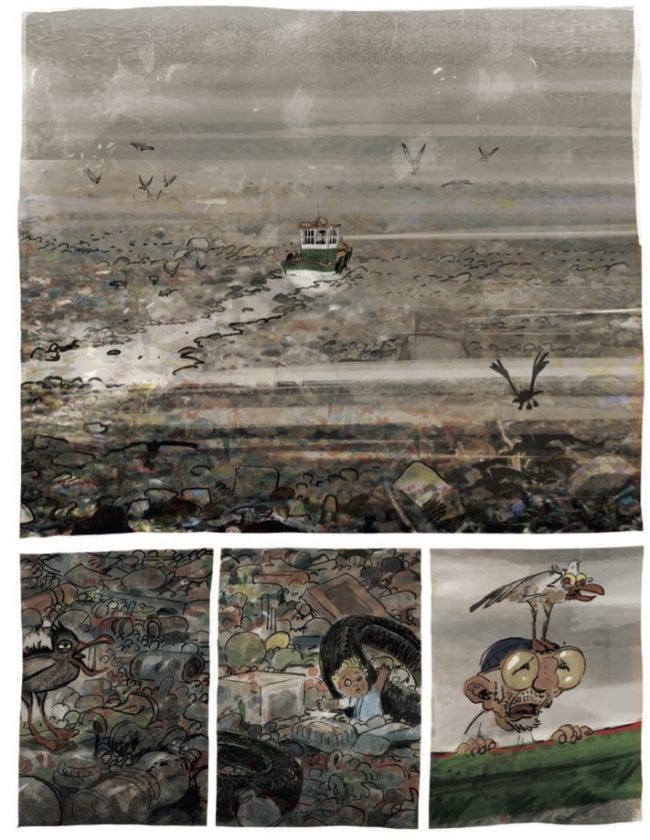

There is an event where the captain of a tanker is culpable for a huge oil spill. Is this connected to the actual oil spill that occurred off the coast of Brittany in 1978, which is considered among the largest oil spills in history?

That one and many more. The Shell huge oil leak in Mexico’s gulf was also a bad one. I’m convinced what we called the “major oil spills” are actually the ones done so close to the coasts that we can actually find the guilty boats or platforms. But many intentional or unintentional “degassing” oil spills are probably done far away enough to remain undetected and unpunished. But in the end, the damage is done.

It seems the captain of that tanker purposely discharged the oil, and the fisherman accidentally causes the tanker to become engulfed in a spectacular fire and explosion, with nothing to suggest empathy for the assumed demise of the captain nor the destruction of the tanker. This offers opportunity for interpreting an environmental message. There are other environmental messages, such as when the sea bird arrives to the stranded fisherman with plastic six-pack can rings around its neck, and then when the bird subsequently scolds the fisherman for tossing an empty sardine tin into the ocean. There are also images of vast areas of floating trash, causing the fisherman to appear distressed. Did you plan these events as a social responsibility call to action regarding the Earth’s waters?

Yes. There are already three of these “plastic made continents” in the oceans. Some are larger than France. When I decided to tell that “love story on the ocean,” I decided also that it would be dishonest to brush the portrait of an idealistic blue and romantic ocean, because my purpose was to show the ocean as it is, not as it used to be, nor as we want to keep on seeing it. My characters are confronted to that reality, and so the reader must be. My purpose was to deal with the ocean as if it was the third main character of my story. I wanted to show it in many different states. It is sometimes beautiful, sometimes angry, dangerous, peaceful, magic, but also wounded, agonizing, almost screaming for help. Thanks to Grégory Panaccione, all of these aspects appear in the book.

This rollicking action-adventure is filled with varied vignettes and topics. Are any other themes represented that you are especially passionate about?

This rollicking action-adventure is filled with varied vignettes and topics. Are any other themes represented that you are especially passionate about?

One of the main topics is actually the love story in itself. I was interested in telling a love story, but not the regular story of two people meeting and falling in love, not the first time passion. Most of the time, love stories are actually “first days passion” stories. I wanted to try to show the beauty and the strength of a long lasting love. So my characters are not in love since yesterday! They’ve been living together for a while, their love is not very . . . spectacular, but I wanted to see if, from such a “routine love” situation, I was able to rise a bit of oneirism, with the help of a few sardines and a seagull.

The wife is depicted larger than the short and somewhat diminutive fisherman. Does this give her dominance, or in what situations and how does this give her dominance?

Here again, I like to go against the classic proposition, of the strong hero doing what has to be done to protect his fragile loving wife. I wanted to have a fragile male character, I wanted him to look like a small fish stuck in the net of this big factory boat. And on the opposite, I wanted a female character who looked strong, determined. She’s very brave, in the book! She spends all her money to get on a boat, though she knows she gets sick on boats, to sail across the ocean to find her husband. She goes to jail. She’s a fighter, to me. But neither of them is in a position of dominance towards the other, I think.

Did you envision the wife and husband to be depicted in this way?

Yes. They’re described this way in the script. Him: small and skinny. Her: big, wide and taller than him. Duos need to be strongly characterized, with sharp differences. But Grégory gave them this specific design which make them so charming and likable.

As a female, I applauded the wife’s fame when she teaches crocheting to the women she meets on the cruise ship, and later I appreciated that her crocheting from Brittany appears in a fashion magazine and influences the turn of events in Cuba. She is a woman from a traditional geographic area, leading a traditional life, covered in a long black dress with long sleeves, and a culturally-specific headdress known as a coiffe. Yet now the young, svelte, bikini-clad women on the ship clamor for her traditional craft and want to emulate her style, and women who are well positioned and close to power in Cuba also clamor for her craft and style. This seems to turn sexiness and culture on its head. Will you comment on this?

What we perceive as a brand new fashion very often comes from old traditional forms of culture. This is true in many forms of art, clothes, music, dance, painting . . . . We regularly re-discover ancient ways of expression, ancient meanings, and modernity integrates them again into the game. “Haute-couture” designers like Christian Lacroix or Jean-Paul Gaultier built their whole careers upon that rule. Even in dancing, new tendencies such as “twerk” for instance, are actually borrowed from very old and traditional African dances like “Mapouka.” In A Sea of Love, I was amused by the idea that “Madame” just by leaving her village, suddenly became a source of inspiration for modern times. During her whole trip, she’s sharing her culture: crocheting, cooking lobster and crepes on the cruise ship, or htraditional “gavotte” dancing with Fidel Castro in Cuba. She leaves a track in the world. She’s adding a value to the world, by being what she is.

Why did you choose Cuba as a destination for the wife in her quest to find her husband?

I needed a destination that one can recognize right away without text. I didn’t want to have to write “this is Barbados” or “ Trinidad” . . . Cuba has such a strong “graphic” identity that everybody can recognise it from the first panel. This is what wordless writing is about. You have to choose your elements in such a way that you won’t have to explain them with a text. Cuba was perfect for its very identifiable components (Guevara, Castro, colorful houses with old American convertible cars . . . ) and as a final “theatre” for Madame’s journey. Here again, she doesn’t hesitate to interrupt one of the famous Fidel Castro’s everlasting speeches to ask if anyone had news from her husband.

When does this story take place, and why did you choose this time period? Apparently it is when Fidel Castro is still in power, as he is speaking to a crowd of people who are surrounded by armed guards when the fisherman’s wife first arrives in Cuba. A subsequent image clearly shows Castro with his second wife, Dalia Soto del Valle, who was not shown in public with Fidel until 2000, and her likeness is similar to a photo taken in 2010.

I didn’t set the story in a specific period of time because I wanted it to remain some kind of “fairy tale,” as much as possible. There are many anachronisms, in that perspective. My original Brittany village is like “stuck” in the ancient times (very, very few women are still wearing the traditional “bigouden” costume, with the coiffe). And in the same way, we decided to show Cuba through all the visual clichés. I was inspired to do so by the movie Delicatessen, by Jeunet & Caro. In that very weird movie, you can tell you’re pretty much in France, but you can’t really say when, nor exactly where. This produces a distance, and also an environment where you accept that everything can happen, because it’s not history.

Fidel initially has the fisherman’s wife violently imprisoned, after she brazenly interrupts his speech to show him a wedding photo in hopes he has seen her husband. She’s released and then lauded at a party by a general whose (assumed) wife angrily shows her husband a fashion magazine featuring the fisherman’s wife-- an act suggesting perceived injustice. When Fidel learns this, he is furious, and he is relieved to send the fisherman’s wife back to France, first class on a plane. When the fisherman finally finds his way home, we learn his wife’s incident in Cuba with Fidel is in the French media. Based on the somewhat different diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Cuba, and France and Cuba, how might these events be interpreted differently by readers in the U.S. and readers in France?

Fidel initially has the fisherman’s wife violently imprisoned, after she brazenly interrupts his speech to show him a wedding photo in hopes he has seen her husband. She’s released and then lauded at a party by a general whose (assumed) wife angrily shows her husband a fashion magazine featuring the fisherman’s wife-- an act suggesting perceived injustice. When Fidel learns this, he is furious, and he is relieved to send the fisherman’s wife back to France, first class on a plane. When the fisherman finally finds his way home, we learn his wife’s incident in Cuba with Fidel is in the French media. Based on the somewhat different diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Cuba, and France and Cuba, how might these events be interpreted differently by readers in the U.S. and readers in France?

I don’t want to go to far into explaining the book, precisely because I think what is interesting is how readers from different cultures will interpret some scenes differently. But to me, these elements of the story clearly emphasize the ambivalent attitude of the leading classes in communist countries with occidental and capitalist culture; officially, they despite it and condemn it, but very often, they are huge fans of it. We all know how much Kim Jong-un loves Disney, for instance. I’m also always fascinated to see how “famous” people from the fashion industry, music, or cinema interfere in politics and can push some political leaders up or down, according to circumstances. In France, we had many examples of this. President Jacques Chirac trying to seduce the young voters by receiving Madonna at the Elysée, or Nicolas Sarkozy’s communication team working like hell to organize a “personal” meeting between Sarkozy and Tom Cruise, and pretending in the media that the meeting was actually Tom Cruise’s wish! It is always very interesting and very embarrassing. :-)

I’m a huge fan of peritext, and this book does not disappoint in terms of the front and back covers. It’s a tin of sardines!-- even vaguely emulating the sardine tins from Brittany. There is also a humorous literary version of “Ingredients” including “artificial aroma of Virgin Mary.” And, “Nutritional value per 100 gram serving” with “Carbohydrates (sublime landscapes, syrupy melodrama).” There is even an expiration note of sorts: “Best if consumed before the ocean stops making us dream.” The olive-green endpapers look a little like the color of oil in an open tin of sardines. Was this part of your original manuscript, or how did this come about?

No, for the reason I told before. At the beginning, I had not even an intention to publish it; it was a simple exercise. But then it was done, Grégory made a few cover drafts, and they were all very nice but not “wtf” enough to stick to the spirit of the book.

In the same way, I didn’t want a classic “pitch” on the back cover, because I thought that pitching a wordless story was cheating in a way. Wordless is wordless, you know . . . so we decided to try to give as many signals as possible on the cover that the reader was actually holding a very weird object in their hands. That’s why we went into this sardine can design, and decided to replace the classic pitch by a “nutrition facts” section.

The fishing boat’s name is Maria. Is this the wife’s name?

Again, that's a possibility. Another, for instance, is a reference to Columbus’s boat, La Santa María.

Does the fisherman have a name? I would think “Oscar,” as you dedicate the book to “. . . Oscar, my little captain, who travels the globe every day sitting in a box of sardines.”

Our characters have no names in the book, since it is wordless, but they don’t have names in the script either, for I called them “Monsieur” and “Madame.” During the making of the book, Grégory and I always would refer to them as Monsieur and Madame. Oscar, the little Captain, is actually my youngest son. He was just born when the book was released in France.

What would you like to say about A Sea of Love that I didn’t ask?

At the origin of the project, one of my goals was also: try to respect your media, the graphic novel. It is powerful and unique. The graphic novel offers possibilities that no other source of expression does offer. Such a story (with those two old people, those sardine cans, this seagull . . . ) becoming such a unique book, with its “sardine can” aspect, its wordless pages that ANYONE can “read,” even readers who are not French, even someone who is not literate. This is something specific to the graphic novel. It couldn’t exist in movies, for instance, and of course neither in novel, since it is wordless. In the end, we tried our best to use all the fantastic narrative tools that the graphic novel provides, to create both a story and an object. You can find it as an ebook, but you miss a part of the experience.

You have written in a variety of comics genres. Your new books in the U.S. are quite different from A Sea of Love. A new installment in the “Geezers” series, and the delightful The Wolf in Underpants for young readers, demonstrate some of the breadth of your writing. Will you comment on writing for a variety of age groups and interests?

This is again a great force of the graphic novel. Each time I make a new association with a new artist, I become a new writer. Or more exactly, we both merge as one new author. It would be very difficult, as a novel writer, to have so many different literary styles. But as a script writer for comics, you can indifferently write crime stories, adult stories, or children’s stories; you just have to find the right artist to illustrate them. This isn’t the what keeps me on. I never get bored because I have the opportunity to put myself in such a situation that every new project is like a first experience to me. Every artist is different, they all have different sensibilities and methods, and every new collaboration is a new experience for me. As for the content of my stories, I am more and more trying to write for . . . everybody. Not a segmented audience, but just about everybody. A Sea Of Love was made in that perspective, and so is The Wolf in Underpants, in a way. And it is quite difficult, actually, to try to speak to everybody without being too simple, with fading everything to it’s more basic essence.

Do you like sardines?

A lot.

A Sea of Love has already received accolades and significant awards in France. I’m rooting for A Sea of Love for Eisners!

Hopefully. That would be an outstanding message for us, regarding this “universal” dimension we wanted to give to our book! I can try to bribe the jury with a couple of sardine cans, if necessary . . .