I have a million questions about the book but first I want to talk about its genesis. Vivisectionary is the first published collection of work that I’ve seen from you -- is that true?

Yes. Everything else has been self-published until now. I’ve been all over the place in terms of style and content, and so I don’t know how recognizable I would be if someone were to pick up one of my minicomics. I don’t know if they would be able to peg it as my work, unless they were super familiar. I’ve been experimenting so much. I haven’t had a long, book-length work until now.

Did you have these particular comics done first and then pitch the collection to Fantagraphics, or the other way around?

I was working on these comics for a good five years or so in a local alternative paper, and also posting them on Studygroup. And so once a month I would put one of these together, and then when I had enough I would collect them and publish a mini. There were three minis in the course of I want to say four or five years, and they were probably sixteen pages each.

Self-publishing is such a job unto itself.

It is.

How was that experience for you?

I didn’t pursue it incredibly aggressively, to be honest. When I put out my first mini or two, I made a real effort to send out copies to independent bookstores and comics places throughout the country that I knew about. It was so time consuming -- I always got a good response but after awhile it just got to be too tiresome. I would sell them at shows and through Etsy, and got plenty of orders through there, and plenty of conversations and friendships through that and through shows. And that was what made the most sense for me in terms of return on my time.

We were both at SPX and CXC this September, and something I’ve been wondering about lately is how much we as artists need those shows. Because like you said, selling your comics through an online shop you can get plenty of orders -- you can have a lot more reach and you can essentially do better numbers and keep more of what you make. How do shows factor into your model?

I love doing shows so much that I stopped looking at the numbers [laughs]. I so enjoy having those interactions and seeing people face to face and discovering minis. As you were talking about the distribution piece, I was thinking about how much people who don’t go to shows miss in terms of discovering, and how much I depended on minicomics – well, floppies I guess – when I was first getting exposed to comics. This would have been the early ‘90s, and they were published by publishers... just like, $2.99 comics, and you could pick up Eightball or Black Hole or Dirty Plotte… without floppies in stores I think you miss out on that discovery, and shows make up for that. But as you noted, doing shows doesn’t make a ton of financial sense, and distributing minis on your own to shops doesn’t make a lot of sense as a creator. So it’s a tough one in terms of connecting people to the work, but the shows are so nice in terms of community.

Were you on panels at SPX -- were you on the motherhood and comics panel?

No -- and I never make it to panels. I wanted to get to that one.

Me too. I wanted to cover it. I just want to understand how people can work on comics and raise kids, I can’t fathom it.

I’m still figuring it out [laughs].

Let’s jump into Vivisectionary – which I understand sold out at SPX and CXC. So you’re posting it on Studygroup, you’re publishing it in pieces as minicomics. Are you picturing it in a collection as you’re working on it?

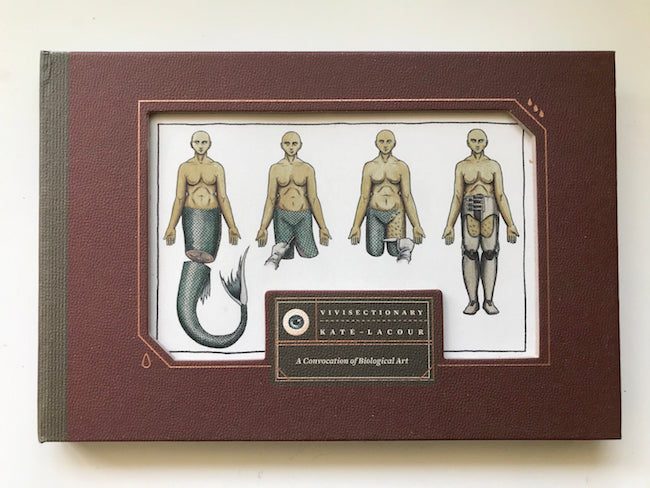

I definitely wanted it to come together as a collection, but I did not give thought to what that would look like in terms of how it would come together in terms of those individual pages. I sat down and was like, oh, how am I going to make this more than just the sum of the parts? It could really easily have been just a “Best of the Family Circus” thing, like one single page image after another, but I wanted it to mean something as an object, and I wanted there to be a story, even an abstract story, that could connect all the parts and see how they could gel together.

Is there anything that got lost in translation between the minis and the collection?

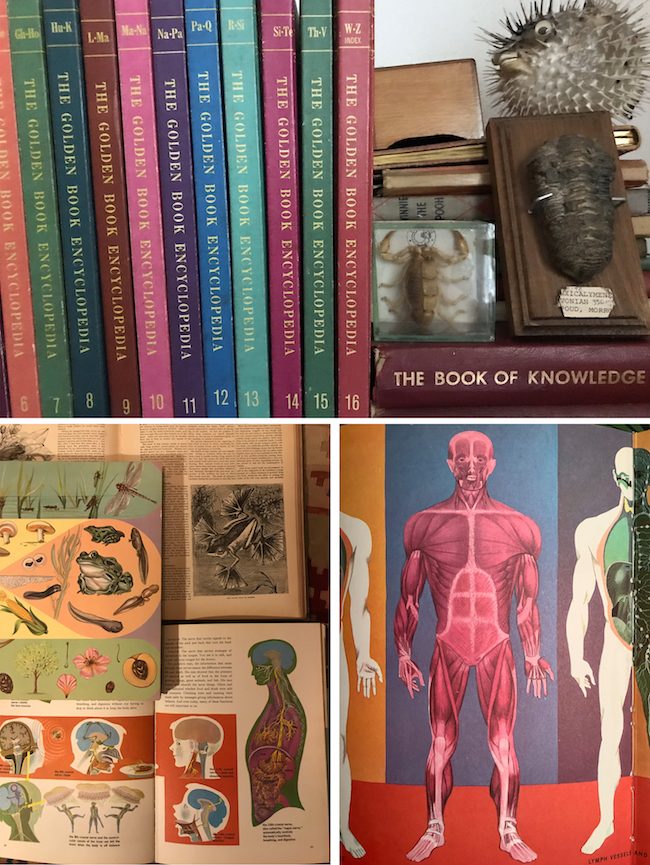

The only thing that I miss is the covers I did for the minis -- they’re vellum overlays, so they’re translucent, and when you peel back the top layer of the cover you can see the image underneath, so it adds something there. I was thinking about old textbooks, which I collect, and sometimes they’ll have informational overlays where it’s like a volcano and when you pull back a painted vellum panel it’ll show you it’ll show you what’s going on inside the volcano. Or the circulatory system painted on one layer and you lift it away and see the musculature underneath. And I love the idea of peeling back skins and additional information coming to light that way.

That is really cool. You seem to have a real appreciation for the art of books themselves -- when I grabbed Vivisectionary at your signing in Long Island City you told me about the marbling you chose for the inside covers of the book and why that was meaningful.

I was so fortunate to work with a really great designer at Fantagraphics, Jacob Covey, who had some great ideas and was also really open to input from me, and I love the way the cover has this die-cut that I was hoping we could do, so it feels a little bit like it’s been incised. And then inside I wanted Turkish marbling for the endpapers. I modeIed the book off of an old encyclopedia, or that’s a little bit of the idea I had in my head. I collect these things, and I read them a lot growing up -- in this country it’s like everybody’s grandparents have these huge, leatherbound collections of encyclopedias. I guess around the time of the Great Depression it was seen as a sort of social mobility thing, like your kids could read the Encyclopedia Britannica, and maybe they would grow up to become doctors. They were sold door-to-door and they were always bound in this very regal, sort of grand way, like “you can enter the great halls of knowledge.” And there would be often gold details and marbled endpapers -- that was something I really wanted to go for.

I love the blobby, globby look of this particular type of marbling, where it’s allowed to form beads on the surface of the water before the paper’s dipped in. It looks kind of like stuff that would be in a petri dish, or blood that they have in the opening title sequence of The Island or Dr. Moreau -- which is the worst movie with the greatest intro.

It looks like a very pretty disease under a microscope.

Yeah. I love the kind of jewel-like look of the illustrations of diseases and cells in those old textbooks. They had this very idealized way of being presented, which is really the opposite of what you’d want. You’d want something very natural and very flawed, but that’s not the way they were usually rendered. If you look at old paintings of the human body -- it’s a mess in there in real life, but in old illustrations the organs are very neat and separated -- they look like pieces of fruit! And of course if you ever do a dissection it’s just a mess of jelly. I love the way of taking these super sloppy things and presenting them in a way that’s lovely, like a floral arrangement.

On the subject of presentation -- the book is divided into three sections and pages are treated as “plates.” Can you talk about how the organization of the book came together?

I sort of spread out all the pieces and said, how do these make sense together? And this has happened a few times in my work where some symmetries that I didn’t plan emerge, and it turned out there were equal numbers of completed plates that fit each of the categories that I was dividing them into.

Without putting too fine a point on it, some of them in the beginning are about animals and nature, then moving on they’re about sex and bodies, and then there’s lots of plates related to drugs and self harm, and things getting a little more out there as the book goes out. So I was happy with not only the way those separated nicely into these symmetrical groups which seemed to make sense, but also the way that when I placed one after the other, it had a sense of going deeper, just like you might go deeper into a body as you took away layers. The first chapter of the book seems a little more superficial, and towards the end it gets close to the bone in a way I find really satisfying.

I do too.

When I’m trying to explain somebody’s work I take this sort of lazy way out where I find other artists where I feel like the work fits in between, and I think I would say your work finds a place between the horror of Al Columbia and the humor of Lisa Hanawalt, and that’s a really nice, really fine line to walk. It would be easy for a book like this to veer into grossout, or grotesquerie, sort of oddities on spectacle -- or just straight into gag humor. But you show this restraint between those two worlds.

I really appreciate that comparison. It’s not something that you would ever conflate the two of them or could easily picture a synthesis of their styles, but I think you’re onto something there. I feel the goofiness and kind of absurdity of Hanawalt and the, not just creepiness, but otherworldly creepiness of Al Columbia’s work also resonates a little here.

That’s not something I aim for, but it’s just the way my personality plays out naturally on the page: kind of goofy, and kind of creepy. The humor and the weirdness -- I don’t know that they ever work together too well. I see them sort of struggling with each other on the page, and I don’t have a problem with that. I like letting that be abundantly and apparently messy. And a little problematic.

A reaction I’ve picked up on a little bit in people reading it is they don’t necessarily know whether to laugh or not, or to be horrified or not. It’s a little too funny to be genuinely scary, but it’s also too disturbing to be just funny. The word that I hear the most related to it is “unsettling.” I feel like the uncomfortable juxtaposition of the humor and the grotesquerie is itself kind of grotesque. You enter a really different headspace when you’re afraid versus when you’re laughing, and I think it pulls you back and forth between those two.

I want to take a look at that last section of the book — where it’s more about substances and altered states than taking apart the body.

I’m trying to remember which of those was the first that I did — it may have been the one with the upside down horse suspended by a hook in space. It’s about ketamine and it’s got the black holes and stuff.

It’s gorgeous.

Thank you. I was doing some pieces about religion, and I was thinking about this dissociative space that you enter in certain altered states, and where that overlaps with the ego death that you experience in profound religious states. I was starting down both those roads, and diverging deeper down — deeper into the ugly realm of addiction and spinning off in the opposite direction towards more religious, spiritual content.

Could you talk a little bit more about how it relates to ketamine? Is that personal experience there, or a subject you were interested in?

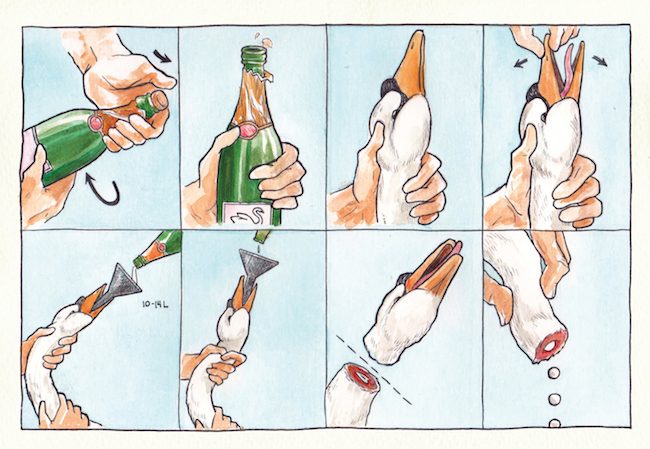

Each of these pieces has a specific, personal, and pretty linear meaning for me, though some of them are more coded. I like that the meaning may be partly lost in translation, like a schematic diagram in another language. But, to explain this particular piece fully, it’s supposed to be an anesthetized horse being hoisted by a pulley, which they do to move a large animal to an operating table. Here, it’s hanging in the wrong direction, suspended in space, with a breathing tube and funnel. The horse’s body is surrounded by diagrams of the way a dead star’s density creates a black hole as it deforms spacetime, with that funnel-like shape morphing into the form of a penetrated eyeball.

It’s a strange thing, you know -- your pupil looks black because it’s a hole. Physiologically, it’s a dark tunnel filled with transparent jelly, and at the end of that are the nerves straight to your brain. You see with it, but you can’t see it, just the empty dark space. Light goes in, hits the fovea, and doesn’t come out, the same as a black hole. When you look into the center of your face, the center of your eye, you’re seeing the darkness inside your head. It’s spooky. You know it’s emptiness, but there’s an unshakeable feeling of presence.

So this piece relates to a single experience, the one time I did ketamine, which is a horse anesthetic, back when I was 16 or 17. I took a dose -- too much, as it turns out -- and was suddenly sliding down this black tunnel and then just complete obliteration. Absolutely without time or physicality, totally without self. And in that non-space, there was this presence, if I can call it that. Utterly without form or qualities, this deep substrate. It seemed to go on forever.

You know, I can’t say it was a good experience, or that it had a positive effect on me. I had an overall bad experience with drugs, and a pretty serious addiction through my early twenties that really held me back as a person and as an artist.

But this particular experience has played a role in my faith. In meditation, in prayer, even, that same... quality of being is present. Something in-dwelling, permanent, a non-self. My religious practice is spotty, my connection is very, very limited, so I lack the authority or insight to discuss God at all. But I can say that, for me, a splinter of that ego annihilation sometimes pierces through in a meditative state, and it was instantly familiar to me from the start after having had that dissociative drug experience. It’s a weird connection, isn’t it?

There are some people I can see picking this book up and saying it’s not a comic, or some I can see picking it up and saying this is absolutely a comic. How do you feel about how your book is classified? Does that matter to you?

It’s funny, it wasn’t until Warren Ellis gave a little plug to me in a newsletter, like, “check out Kate Lacour’s freaky neocomics!” that I was like, “I guess they are!” It hadn’t really occurred to me. I did them in such a way and thought of them as so sequential that it wasn’t until I saw that reflection of my work in someone else’s words that I went back and looked, and realized I’d gotten away from a traditional ABCD format. And it probably doesn’t meet the Scott McCloud definition, because there aren’t panels in most of them.

I don’t think it matters much. I think of them as comics. I’ve also tried to make the book itself as sort of a comic, for example the images on the plates on the left hand side are sequential but not juxtaposed.

The form of the book is its own system that you have to come to understand as you’re reading. I think that’s where I was feeling a kinship to like, Pim and Francie, which is that it’s narrative-centric but it’s not a sequential story. It’s a sort of formalism.

It's a lot of embedded and concentric narratives, and I hope that it’s put together in a way that’s intuitive enough for people to discover.

It also kind of feels like an artifact from a bizarre time in history — like something John Harvey Kellogg or the goat testicle transplant guy (John R. Brinkley) would point to in a lecture. Like a pseudoscience textbook.

[laughs] Yeah. Thank you.

You have a nice afterward in the book about dioramas — is that how you would ideally like these pieces to be seen?

Oh my god. I would love to do dioramas of these. I have put together not full scale dioramas, but taxidermy display cases that I think captured the same feeling.

I know that you would never look at these and intuitively think of a taxidermy museum display, but for me, that crystallizes everything about the story of science that so fascinates me. That’s the feeling I’m hoping to evoke a little of. It’s contrived in the same way that that jewel-like presentation of the body is often wrong and artificial, and at the same time they are, within the aesthetic rules of the diorama, so natural. You know, the little violets are piercing through the snow, and the weasel is running across the snow and leaving these perfect little footprints. And it all seems to be moving and at the same time seems terribly posed as well. Like a tableau vivant. Alive and completely fake. It says so much more about the people who put that together and the moment it was created for than any of the nature it purports to represent. I love that so much. It’s not the male gaze, it’s the human gaze.

I never thought about that, but the way we present that natural world is like an extension of that point in time’s particular ideology. Is there a specific point in time that you’re referencing in Vivisectionary?

I looked at things between the turn of the century – some of the 1800s as well – through the 1950s. The field there has certainly changed a lot, but there’s still this sort of World’s Fair, great thrust of progress feeling. This sense of, “God gave us dominion over this,” a sort of noble stewardship sensibility towards nature. Also this great sense of projection onto it, the same way a man might project a lot onto a woman’s body. This sense of the great openness and availability of nature, its being both our house and our child, but not a sense of belongingness to it. A real sense of nature as subject.

Has biological art always been of interest to you? How did you come to it?

Always. I’ve always been totally taken with this stuff. When I was, gosh, younger than my oldest son, so probably six, I had a BBC set of tapes called Life on Earth that I got for Christmas, and I literally wore the tapes out. I had a bunch of encyclopedias that belonged to my dad, so they must have been from the ‘50s, and when I got tired of my picture books I would say, “dad, read to me about volcanoes” or “dad, look up raccoons tonight.” We would read sections on nature stuff together. And we lived in New York so I would always be begging to go to the Museum of Natural History, which is just so exquisite. Every time I go to attend MoCCA or something like that and I have a couple of hours I always sneak away there, and visit the halls that have not been renovated, they’re just marvelous.

I didn’t know you were a New Yorker.

Yeah, I grew up in the suburbs. I would always take the train in and take my mall job money to go to St. Mark’s Comics and peruse the back racks.

But that’s not how I discovered comics, it was when I was at boarding school and was in a bookstore in New Hampshire, and they happened to have a copy of Dangerous Drawings, which was a book put out by RE/Search. It had interviews with people like Julie Doucet, Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, and Aline Kominsky-Crumb, and I was just enthralled. It exposed me to so many good people in one spot, and I spent the next several years trying to track down books by each of them. This must have been pre-internet, because I remember it being a real quest.

Were you just carrying around a list with everyone’s name on it at all times, like, ready to go? That’s what I used to do.

Yes, pretty much! I would take the train to Boston and go hunt down stuff at Newbury Comics. In the process of trying to find XYZ, I would find other comics. But it was definitely very haphazard. Very random.

That’s kind of the best way to discover things I think. There’s something about that that I miss.

It’s a treasure hunt.

Yeah. It goes back to what you were saying about comic shows. They’re their own little treasure hunt, some for the good, some for the not-so-good.

I agree with that.

I’m really excited for people to discover your book. I don’t think that there’s an equivalent for this in comics right now. Who were you looking at in comics that started getting you thinking about making your own?

Phoebe Gloeckner was drawing the stuff that was closest to what I had been drawing at that time, it must have been when I was in 10th grade. I was like, “this is what I want to do, and she’s done it, and she’s done it so well!”

Had you seen her RE/Search cover?

Yeah, she was on a few of them… her illustrations for The Atrocity Exhibition, I actually had trouble reading that book. I remember getting a hold of it in 10th or 11th grade and my hands were shaking, I was almost like, “nooo!” It’s exactly how I had hoped to be able to express myself some day, and she was there and she was doing it. It was amazing and devastating. I loved her work.

I don’t know that anyone influenced me in terms of being a cartoonist, but that said there are a lot of people who I wouldn’t have done comics, or have done the same comics, without. Because if not their style or content, the way they approached comics inspired me to make them more seriously or more deeply. For instance, someone like you mentioned Al Columbia, or D.R.T. -- they’ve got such a beyond the veil vision and do it in a way that seems so fully realized, it’s as though you are trying to watch a channel that your TV doesn’t receive. You’re just getting a little bit of this fully formed vision. I love that. It feels like when you’re trying to attune to a higher state and just a little bit of it manages to fizzle through into your very limited worldly and distracted consciousness.

Then there’s people like Nina Bunjevac or Jim Woodring who draw stuff that’s really, really out there but with such a high degree of precision and technical expertise and absolute mastery over the subject matter, even though the subject matter seems so raw, it’s done in a crystalline level of rendering. I find that really inspiring, too. That makes me want to be more aggressively visionary and also more technically rigorous. People who are attacking the page with that kind of ferocity, but not in a feverish way, in a way that’s very masterful -- that has done a lot to make me apply my thinking in my work more deliberately. Like, in deadly earnest. Even when it’s goofy and even when it’s grotesque. I’m all in. I don’t want to hold anything back at any point. Even if it’s very embarrassing or difficult or ugly.

I’ve been looking at a lot of fetish artwork lately for reference--

Love that.

--it’s like they have a very specific vision, they know what they want to see, and that is what they go for.

I think you can’t be that kind of person without a sense of humor about yourself, and yet there is no humor in those images. They’re in deadly earnest. Typical sex we all know and you don’t have to put the nerve ending itself out there, because it’s sort of understood where that lies. And in something like an image of extreme rubber fetish that someone has drawn they really had to lay that completely bare and make that fully available. There’s something so exciting about that.

You mentioned to me that you got kicked out of boarding school for reasons related to Guido Crepax's Story of O. Can I get that story?

[laughs] Well, I love that you’ve championed the work of Guido Crepax. His Story of O was one of the first adult adult comics I picked up as a young person, just like you, and it made such an impression. His storytelling and line are so wild and free and unencumbered by convention -- it would be a strong approach in any context, but it’s just perfectly suited to erotic comics. I don’t usually go crazy for stylish, cinematic comics art, to be honest, but his work’s also just wonderfully eccentric and grotesque, like the art of Franz Von Bayros. And I love to see an artist with a really idiosyncratic vision that they’re fully committed to. So it’s been cool to hear you prosthelytize and to see the Fantagraphics collection published.

Part of my story with Crepax involves getting into some pretty hot water over that particular book as a teen. I went to boarding school for high school, and was a bit of a black sheep. So at one point my room was searched for contraband, and in the course of that my comics and zines stash came to light. I remember I had Story of O, Boiled Angel, Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, Answer Me!, Dirty Plotte, some Tom of Finland art... I don’t know whether I was more uncomfortable or the headmaster, actually. He also turned up an empty vodka bottle; I was such a little tree-hugger that I’d held onto this big plastic bottle because I wanted to be sure to smuggle it into a recycling bin instead of just dumping it in the nearby dumpster.

In any case, I think the Crepax et al. comics were the deciding factor in their asking me not to come back the following year. I think they could have moved past the bottle, but the comics were way outside the scope of normal and seemed to reflect a really unsavory character. Which was, in fairness, not a totally unreasonable conclusion. But it’s made it especially fun for me to see the work of Crepax, and other kind of raunchy or outrageous artists like that, elevated and analyzed, and honored. I get to see the stuff I used to hide under the bed displayed on the coffee table.

Kate, it’s a pleasure talking to you. I feel like I could talk to you all night, and maybe at some point we should.

I would love that.

Til then.