My second interview with the current residents at the Maison de Auteurs is with Antonio Hitos. Antonio got his start in the comics scene at the end of the '90s with the Huelva fanzine muCHOCOmi. When he was 18, he moved to Seville to obtain a degree in Audiovisual Communication and from there began collaborating with other fanzines. Shortly after, he began publishing in the magazine El Víbora until its closure in 2004. Inercia, his first graphic novel, received in 2013 the VII International Graphic Novel Award Fnac-Salamandra Graphic, and earned him nominations for best work and author revelation in the comic lounges of Madrid and Barcelona in 2015. I met up with Antonio after lunch to discuss his newest project, ideal cartooning, and the end of youth.

My second interview with the current residents at the Maison de Auteurs is with Antonio Hitos. Antonio got his start in the comics scene at the end of the '90s with the Huelva fanzine muCHOCOmi. When he was 18, he moved to Seville to obtain a degree in Audiovisual Communication and from there began collaborating with other fanzines. Shortly after, he began publishing in the magazine El Víbora until its closure in 2004. Inercia, his first graphic novel, received in 2013 the VII International Graphic Novel Award Fnac-Salamandra Graphic, and earned him nominations for best work and author revelation in the comic lounges of Madrid and Barcelona in 2015. I met up with Antonio after lunch to discuss his newest project, ideal cartooning, and the end of youth.

Sloane Leong: So, my first question is: what are you working on?

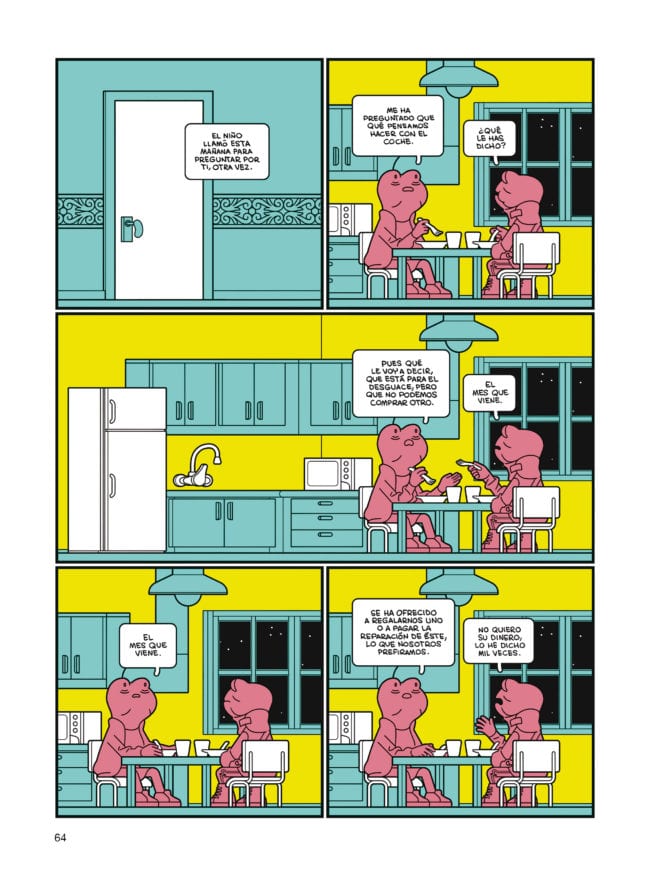

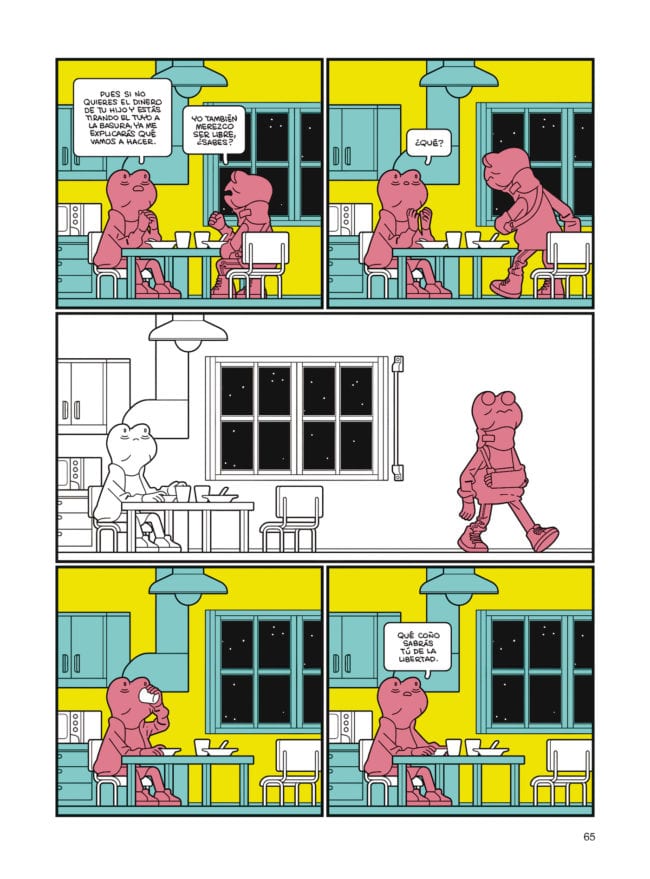

I’m working on a graphic novel called “Noise”. It’s about this very cartoony character that keeps encountering conversations about the physics of void and emptiness.

Okay.

And that serves me as a kind of metaphorical background to talk about the end of the youth of the character. I tend to go back to that topic.

Oh really?

Yeah, most of my characters are very much alike in that sense.

Hmm, why is that?

I’m very interested in physics and science in general, and I find that when you use it as a tool to look at everyday stuff, you often see new meanings in them. Through the distance that science gives you, you can make the exercise of looking at things as if they were not related to you, as if they were not—

Personal?

Yeah, personal. As if they were alien to your human condition. And so, the idea of the end of youth, a moment in life in which you are confronted with this sort of sadness and you start giving up on some of the things you used to fantasize about, seems to me to connect very well with these concepts of void and emptiness.

Right, very interesting.

I don’t know if I was making much sense.

Yeah, that makes sense. I mean, there are a lot of metaphorical parallels there. What moves you to talk about the end of youth specifically? Was it something personal for you, that it was so impactful to have that kind of like stark end of—

Yeah, that makes sense. I mean, there are a lot of metaphorical parallels there. What moves you to talk about the end of youth specifically? Was it something personal for you, that it was so impactful to have that kind of like stark end of—

No, I’ve had a pretty standard life, no big concerns. What interests me is this switch in the way you think when you come to terms with the fact that you are actually growing old. You realize that many of the things you planned for will never come about, and you start seeing the cracks in some of the ideas you were most attached to. That brings you to the realization that you can’t ever be completely right, and so you gain consciousness about all of those grey areas. People around you start changing and you are also changing, and then you start making decisions that are gonna influence the rest of your life and that can be scary. Losing that purity is, to me, a bit sad in a certain manner.

Yeah, there is a whimsicality that goes away. This ease of possibility in your mind when you hit that certain age.

Yeah, that’s why this is a subject that’s very recurring to me. This is going to be my third graphic novel and in my previous two there’s also a lot of that. I find it interesting to write about these ideas.

Very interesting. And from the pages you just showed me, it looks like there is a single sequence the character is going through. Is that true through the whole book? It’s just a linear thing or is it more—

Very interesting. And from the pages you just showed me, it looks like there is a single sequence the character is going through. Is that true through the whole book? It’s just a linear thing or is it more—

It’s not through the whole book, but it’s close. It’s the first time I’m trying something like this. I’m very interested in cartooning as a language, so the closest I can get to the basics of it, the better. Moving the camera around, or changing the point-of-view, or exploring things as you would do in a more kind of cinematic way seems to me to take away from the purity of cartooning. I mean, I see the value in most other ways of doing it, but to me this is how it works best. So things like the sound effects and the expression lines and all of that are a very integral part of my drawing, they occupy a physical space within the image. And I find that the way you look at a character moving through the panels inside the world that you’ve built for it, creates a kind of rhythm, a melody. I feel like that gets you closer to the essence of cartooning. I see this very clearly in the work of people like Herriman or Schulz.

Very cool. Yeah, it’s interesting, your style is so exacting. And you’re saying there is a rhythm to how you’re paneling and having the character move through space, so it’s very methodical for the reader to follow through the story.

Yeah, exactly.

How did you go about planning and deciding on that look for the story?

I’ve tried to give myself some freedom to improvise. What I would do is plan the actions and give each of them a number of pages that I foresee will be enough for them to be told properly. And then I start doing very loose thumbnails, because I don’t want to be too constrained by them when I start penciling. It hardly ever goes as I originally planned, because although I’ve got an idea of the things the character needs to see and do for the story to move the way I intend it to, I also want to have room to move freely if I think the action requires it.

Right.

Because it’s that music that I’m looking for.

So you’re flexible to where the story takes you.

I try to be. But then I’m also very concerned with the bigger structures, and I measure the different sequences in relation to each other. So, if I’ve got this one episode that is twenty pages long and I somewhat want its structure to be related to another episode later on, then that’s got to be also twenty pages. When these connections start happening the story kind of writes itself.

Oh, okay. Interesting. That’s a very mathematical approach.

It is very mathematical, yeah.

That’s cool. What are some challenges you’ve faced while constructing this story?

Well, I’m mostly afraid that when I’m constraining the story in those mathematical terms, it might affect the way it flows. But I try to balance it. My stories, as in the narrative of it, don’t really have that much weight in the work. It’s more about the concepts I’m exploring and the visual side of it. So yeah, that’s a challenge, but if those codes are taking away from the story but adding to the clarity of the concept, then I’m okay with it.

I was wondering, you said that you return to the theme of losing your youth and that pure mindset—do you care at all about being repetitive or do you make efforts to kind of find new interpretations of this theme?

In a certain way I don’t think I mind being repetitive. Some of the authors I enjoy the most you could say are actually very repetitive. Not to put myself in that category, but look at Schulz or Ware, for example. Even though they seem to be drawing the same thing over and over again, it keeps getting more sophisticated the more they do it. I feel like I’m chasing something, like I want to create a perfect archetype of this young person that’s about to lose his youth and is living in a very cartoony world where anything is possible, but then nothing really happens. And I feel like with every new book I get a bit closer, and I’m perfectly okay with that.

Yeah.

But then again, I’ll be fine if someone thinks that this is still all the same. And it probably is to an extent. I just want to get to the most essential features of these ideas and try to represent them with as much clarity as possible.

You mentioned George Herriman and a few other artists. Who else inspires you? Or who else is feeding into your project?

My biggest conscious influence I’d say is Peanuts by Schulz. Everything is in there, and that’s where I go back to when I need to clear my mind. His characters are barely scribbles, and yet they have such life and are capable of conveying so much emotion. It’s so small but so big at the same time. Perhaps what I like the most about Schulz’s work is how pure it is in the way it uses its language, relaying solely on the elements that are exclusive to comics. Most of the authors I admire are in that same vein. Ware, DeForge, all of those. Also, aesthetically, I feel very attracted to stuff like Garbage Pail Kids or Ninja Turtles, and I like that to show in my work. I populate my backgrounds with graffitis, ooze coming out of tubes, trash everywhere.

It’s interesting the commonality between all these artists. I feel like they’ve always had a very clear picture of how they want to express themselves through their style. Have you always felt like that? I feel like a lot of your work has always had a distinct style, a distinct preference for how you tell stories…

Yeah, I suppose it has mostly been a constant thing for me. I also enjoy styles and media that are not related to this particular style at all, but yeah, when it comes to drawing comics, I feel like I’ve always looked up to this guys. I just like comics to feel very much like comics, in a way that no other media can imitate.

So they are kind of your ideal comics, like that tradition is the peak to you?

Yeah, exactly. I feel like Peanuts pretty much accomplishes it all. It can be done differently, but not better than that. You can create a different set of characters or you can communicate a different set of ideas, but as for the craft of cartooning, for me it’s all in there. But then again, and since we mentioned him before, you get Chris Ware’s work and it doesn’t really look like Peanuts at all, but it’s also very pure in its own terms, in the way he builds the page and creates these reading flows that make sense only in comic form. I suppose there’s a certain feeling of pride there, of fully embracing the language. There’s this whole generation of cartoonists now, I’m thinking of Michael DeForge, but also Anna Haifisch or Max Baitinger from Germany, whose work is full of this. Their comics don’t need to make sense outside of the pages themselves, and that is beautiful.

I feel the same. In the past couple of years, especially in the field I’m in which is part of a more rigid tradition, the comics are just storyboards for movies or they’re just pitches for a tv show.

Yeah, that’s a shame. I mean, comics can also be cool just because the story is interesting or the drawings are fun or whatever, they can work that way just fine. But it would be so much better if, on top of that, they were also exploring the possibilities that are inherent to their own language.

Exactly, yeah. I totally agree. What are some challenges that come up when you work in such a…I don’t want to say strict—

It is strict.

Yeah, it is a very mannered way of drawing.

Yeah, it is a very mannered way of drawing.

Yeah, and it comes with its complications. For example, I never really change the point-of-view, so at times I’ll be like, shit, this is not very convenient. In order to tell this thing I want to tell, like this very specific action, it would be great if I moved the camera a bit so I could show the floor. But then it would lose part of the consistency that’s holding the whole thing together, so I just work my way around it and try to come up with a solution. This is how it goes for everybody to a certain extent, you work with your limitations. Some things you just can’t do because you don’t know better, but some other limitations are self-imposed.

Yeah, that kind of reminds me of the Oulipo movement, do you know that movement?

Oulipo?

It’s like O-U-L-I-P-O. I think it’s like a French literary movement. The idea is to build a work based on a set of very specific constraints. So, write a whole story without using the letter ‘E’ for example.

Oh, okay.

This cartoonist Roman Muradov, I think he was a resident here at some time. But I know he kind of applies that philosophy at times in his work, the application of limitations almost becoming like the seed to the story.

You end up with very cool books, because they’re very unique. They only make sense on their own terms.

Hmm, totally.

This is what happens when you see someone’s work and you immediately recognize it. And then you start seeing traces of their work on the work of other people that have been influenced by it.

Yeah.

It takes a lot of commitment to develop a recognizable style. I feel like Peanuts is a perfect example once again. You look at how it developed for 50 years, and you see that the way he drew the strip when it ended had nothing to do with the way he drew it when it started, but it was a very gradual change that was invisible on the day by day. By repeating the same thing, you are also perfecting it, or at least making it more intimate, more personal.

Right.

I suppose that if you stick to these self-imposed codes for long enough, eventually you end up with something that is more sophisticated than the codes themselves.

Yeah, for sure. I really like that aspect of your work. Because you’re so committed to your point-of-view and your own rules and logic in the book. That’s what I enjoy when I read books.

I get my fair share of doubts as well. I’m not always sure that I’m doing the right thing.

Yeah, yeah.

Sometimes it feels stupid to hold on to this extremely strict way of doing things, but you just keep going.

Yeah, like the reader won’t know at the end. To them, it’s finished, neatly composed. I like that even though you have these very stringent rules, your work is still flexing and changing as you need.

Yeah, thank you. Thank you very much.

It’s very cool. So, I guess you’ve been at the Maison a couple months now?

A couple months and a half, yeah.

How have you been enjoying it? How is your experience?

It’s been amazing, I’ve been meaning to come here for a long time. They give a grant once a year in Spain to come to the Maison and I’ve been applying to that for a while and I finally got it this year.

Wow, cool.

Yeah, the best thing for me is that this grant allow me to focus solely on my comic, whereas normally on top of that I’d have to do illustrations for clients to sustain myself. That back and forth makes it a bit tricky to hold on to all of these codes we’ve been discussing, because you spend a lot of time away from them and also accommodating your style to whatever it is the client needs, and you keep getting all these doubts, so it’s great that during my residency I’ll be able to just concentrate on my project. On top of that, I got to meet an amazing set of people here. You see the work of all these different artists and everyone’s got their own very particular views on the language of comics, and that is very enriching.

Yeah.

So yeah, I’m loving it here. I had been to Angoulême a few times before for the festival, but this is my first time actually living here. And I’m enjoying it very much, I’m going to be very sad when I have to go. [Laughter.]

Yeah, it’s pretty awesome here. I’ve got to admit. You talked a little bit about your hometown and working in comics. Can you talk about the comics scene in Spain?

It’s amazing. The comics scene in Spain is actually amazing. Creativity wise, this is probably one of the best moments in Spanish comics.

Really?

Yeah. The talent coming up at the moment in Spain is overwhelming. There are a bunch of reasons why this is happening, but I feel like one of the most important is that these artists are embracing the language of comics for what it is. They’re not doing comics as a platform to do anything else, they’re just doing comics for the sake of it.

Very cool.

Some of the younger indie Spanish cartoonists are being translated into other languages now, I think, in higher rates than ever before. On top of that, there’s also a good number of Spanish artists working for the bigger companies in foreign countries. It’s an excellent moment in terms of the quality of what is being produced. I don’t know if our industry is gonna be able to support all this talent in the long term, but that’s a whole different story. We’ll see how that goes.

Is it hard to make a living on comics there?

It’s hard, yeah. It’s improved greatly in recent years and comics in Spain now hold a position as cultural items that have been elusive before, but the market is still not big enough to sustain the average author. Some people manage to break that roof and reach a wider audience though, so the possibility is definitely there. I’m optimistic about the whole thing.

Awesome. Let’s see, so the book you’re working on now, do you have like a publishing date on it yet? Or when it might be out?

No, not yet. I don’t want to commit to a date cause it’s still very early on. I started drawing it when I got here, so it’s been only two months.

Oh, okay. So it’s very new.

Yeah, it’s very new. I’m guessing it might take me around a year to complete, but I really don’t know yet. It might be a bit more, a bit less.

Nice.

Yeah! But I suppose 2020 will be a safe date to say.

Nice, awesome, very exciting. Well, thank you for talking with me.

Oh, thank you very much, thank you.