SENECA: Sure. So you’re working at the newspaper…

MARRA: Right. I was working at the newspaper on Saturday nights, I was in grad school for two years -- first day of classes was September 11th, it was crazy, so that was sort of like a specter throughout the rest of my time there, especially cause we’re going to school in midtown Manhattan. At this point I’d forsaken children’s books, I was just gonna do weird shit for two years, I didn’t care what happened. A lot of the time I wasn’t even making things that were commercially viable, I was just doing weird stuff. I was influenced by Marcel Dzama at that point. I don’t really know what I was doing, I was just experimenting in my first year. And then my second year I worked with Mazzucchelli, I asked him to be my thesis adviser. I’d decided in the summer before my second year that my thesis was gonna be about the Rwandan genocide. I was gonna do a hundred paintings to represent the hundred days of the Rwandan genocide, because I was taking shit so seriously still.

But then in my spare time, I really had these two art lives. I would do my real art for school, and then I would do my personal art in my spare time, so my personal project for that summer was adapting A Princess of Mars into a comic. So I would spend all day working on this thing, and then I would like, think a little bit about the Rwandan genocide. I mean that’s a really powerful moment in time compared to a fantasy novel, but—

SENECA: But you don’t want to spend your whole life in the Rwandan genocide.

MARRA: No! But I thought that that was what I had to do to make serious artwork. It’s just an art school sort of thing.

SENECA: Totally. So what did Mazzucchelli think of this?

MARRA: Well, I had abandoned that idea before I had to start on my thesis. My roommate was like, “Dude, this John Carter thing should be your thesis. This is what you wanna work on, why don’t you work on what you want to work on?” And I was like, “Fuck, you’re right!” So I decided going into that semester I was gonna do a comic -- but it was gonna be an original comic. So my professor David Sandlin asked me who I wanted to do my thesis with and I said Mazzucchelli, because Year One was one of my favorite comics ever.

SENECA: Yeah, were you totally freaking out when you went to the school that he taught at after growing up with Year One?

MARRA: Yeah, I was like holy shit! This is amazing! I remember I went to his class and he was pretty apprehensive about taking me on as an advisee. I mean, he didn’t know who I was at all, or what my commitment was. He said I had to take his class, the comic-book workshop class, and then he’d think about it, and eventually he agreed to do it.

SENECA: Had you kept up with his work? Did you know about his big transition?

MARRA: Yeah. I knew about Rubber Blanket, I had seen it, and seen ads for it, but to me it seemed natural at the time. It didn’t seem like some big transition away from superhero comics. To me it’s sort of the same now, there are different kinds of comics but they’re all the same thing…

SENECA: Yeah, I think if you look at it in hindsight that transition feels pretty natural. It’s weird more dudes don’t do that. Where’s the John Romita Jr. Rubber Blanket?

MARRA: Exactly, yeah! Or Jim Steranko — I guess Steranko did some weirder stuff. But nothing like Mazzucchelli. I think Mazzucchelli still is one of the few big mainstream superhero comic book artists to launch into making work with a totally different aesthetic.

SENECA: Yeah, he’s unique. You could make the argument for Darwyn Cooke, but I think that’d be pretty facetious at this point.

MARRA: It would be hard. It’s not to the same degree, and Mazzucchelli’s aspirations are pretty lofty. His stuff is amazing to me. But I wasn’t as aware then as I am now about that switch. So yeah, so we started working on my thesis, and for the whole first semester we just worked on the mechanics of the comic.

SENECA: And this is the first comics class you’d taken, right?

MARRA: First and only. Everything else was just intuitive or self-taught. But Mazzucchelli’s class is the comic-book class to take. It’s the perfect comic-book class. I don’t know how you could teach comics any other way. It’s incredible. He is as good at formulating a comic-book class as he is at constructing comics himself.

SENECA: So what hit with you, what were the big points that you took from that?

MARRA: Every single week I’d get my mind blown, because he starts off very simply and then works into something more complex, but the thing that really was devastating for me was understanding -- and this sounds really basic, but it’s amazing how I didn’t understand that the words and pictures do different things. To illustrate that he showed this Chris Ware comic from Raw, where the drawings are this very typical superhero comic and the words are just a totally different story. And I remember he was critiquing one comic I had done, and his criticism was the words and the pictures are doing the same thing. That was probably the biggest. That’s one of the most foundational understandings of comic book mechanics ever that he gave to me. I remember hearing Chip Kidd on NPR years later when I was living in Philly, talking about the first day he walked into design class, where the professor drew an apple on the chalkboard and then wrote the word “apple” underneath it and said, “Never do this.” Never — it’s the first cardinal sin of design. And that’s the same thing with comics; the words and the pictures convey different levels of information. And being aware of that and manipulating that generates power, and friction in the story.

SENECA: Did you understand at the time that that was why you hadn’t liked first-person narration as a kid?

MARRA: No. Third-person narration is the way to go, and then thought balloons — I think that they’re an absolute necessity. But it wasn’t until much later, until I actually started crafting comic books, that I understood. Mazzucchelli ran me through the wringer, process-wise.

Anyway, I’m doing this original comic that’s sort of a reaction to 9/11. It’s an homage to Kirby; this was the time that I sort of discovered Kirby. I went to David Sandlin and I said, “I want to do a Kirby comic for my thesis, like a propaganda Kirby comic about 9/11.” And I created this superhero: he’s a veteran, but he’s an alcoholic and he sees himself as a superhero in his fantasies, and so when 9/11 happens he goes and fights Osama bin Laden but it’s all in his mind. It was a lot of really controversial ideas about American foreign policy. I was reading a lot about that at the time, because I didn’t know what the fuck was going on in the world after that happened.

So I wanted to do a Kirby comic, and David Sandlin said I should either talk to Gary Panter or I should talk to Mazzucchelli. And I was like, Mazzucchelli, because I wasn’t really aware of Gary Panter as much. I had some Jimbo comics, but to have Mazzucchelli available was like, "This is crazy." I sort of wonder what would have happened to me if Gary Panter had been my adviser.

So Mazzucchelli and I worked on this 64-page comic book epic that was way too long and too ambitious, and for the first semester I did hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of layouts pages. It was sort of back to this way of working from my undergrad years, where you figure out every problem and you solve it, and then when you’re actually drawing it’s just all execution.

SENECA: And you were doing sort of a Kirby style. How quickly did you move away from that afterwards?

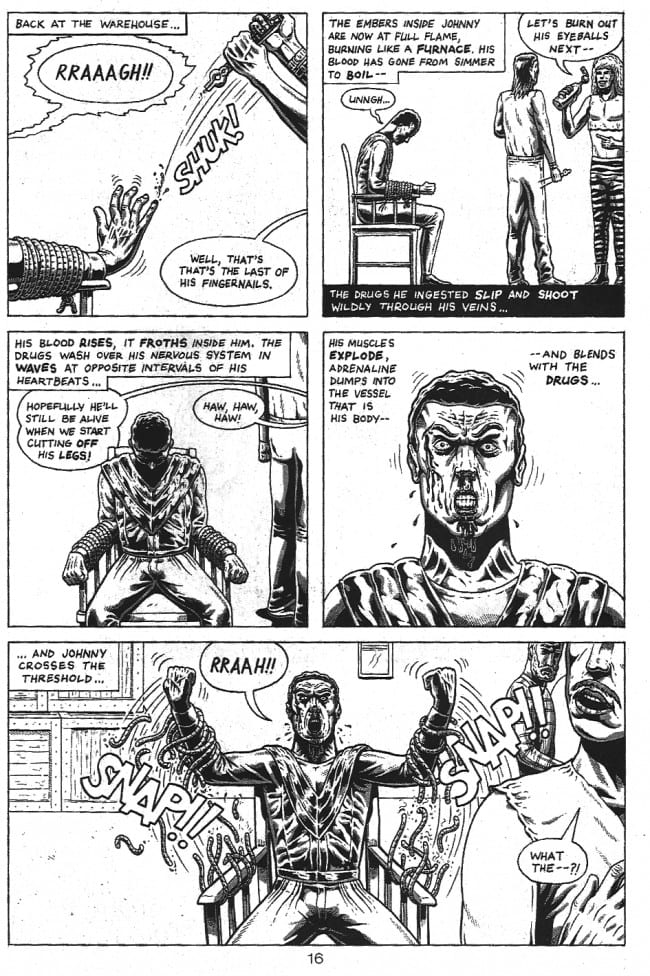

MARRA: Actually when I drew that, it didn’t even feel natural when I was doing it. I was trying to create this pseudo-Kirby way of working, and that just isn’t natural for me. But some of the drawings that I had done of the character, the studies and sketches trying to figure him out, I showed them to Mazzucchelli, and Mazzucchelli said, “You know, if you’re trying to do this like Kirby, you have to remember that Kirby always considered himself a cartoonist.” So that really hit me, and I augmented my approach to get that result. But it wasn’t natural for me, and I think that’s why it was so difficult for me to finish that comic. My natural way of working is probably closer to Night Business.

SENECA: Still trying to convey realism but without doing actual realist drawing?

MARRA: Right, right. So I graduated from grad school and went to Philadelphia, and that’s where I started trying to hone that side of me. That was after looking at American Century, which was artwork by Marc Laming, inked over by...

SENECA: Was it John Stokes?

MARRA: Yeah! Yeah, it’s John Stokes, who I love.

SENECA: He inks Phil Jimenez too.

MARRA: Yeah, I love those Invisibles issues they did.

SENECA: The ones where he’s tied up, trippin’ balls…

MARRA: Totally. That stuff is what I was kind of aiming for when I started Night Business. Also looking at Rex Mundi, looking at Eric J’s drawing, I was like, “Man, I can do this shit!” That’s what put me over, that was when I finally started to embrace the things I had learned in Italy. It’s not about precision, it’s about this emotional connection between me and the work, and between me and people who see my relationship to the drawing, and their reaction to that. That’s when I realized that you gotta do honest stuff. Because if you don’t connect with your own stuff, nobody else will either. So I started drawing Night Business then.

SENECA: This is interesting, because Night Business is a super-pulpy genre comic, and you’re coming from all this relatively highbrow theorizing about art. What was responsible for the lowbrow pop culture stuff?

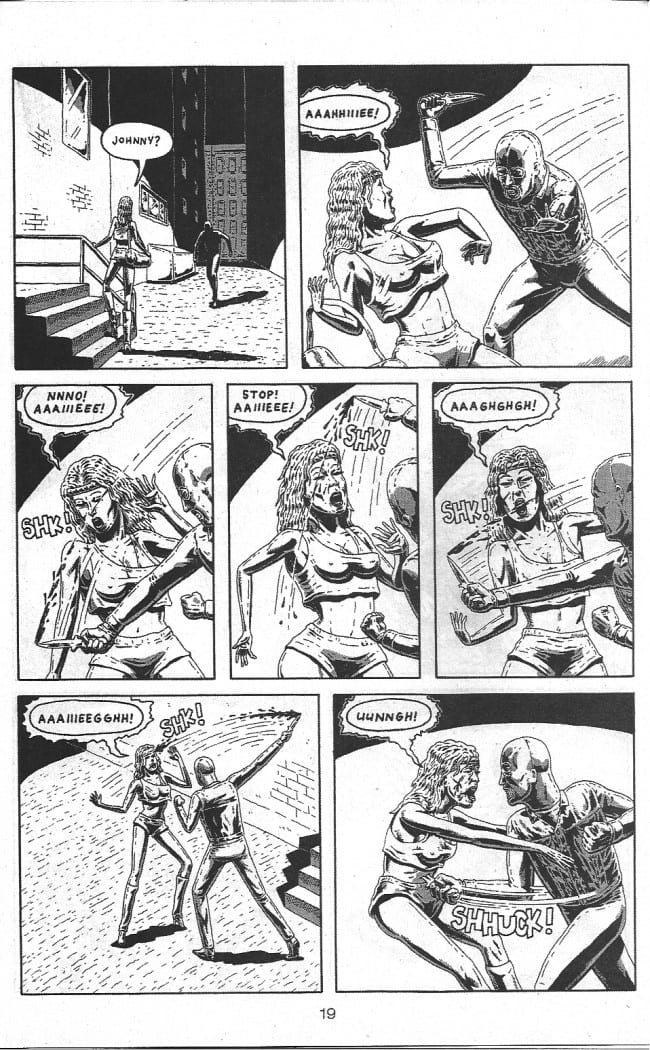

MARRA: Movies. It was specifically from giallo movies I was watching at the time. I was living a pretty depressed existence in Philadelphia, because I was away from all my friends and family. The city of Philadelphia is a weird city, especially for somebody who didn’t grow up there, and it was a weird few years I spent there. It put me in kind of a dark head space. Also, when you’re in your mid-twenties, you’re going through some ... adjustments. So a friend of mine was in town and we went to the video store, because I rented videos all the time, I had nothing to do. I was super-poor, but I bought a DVD player and a TV, and they had this great DVD rental place with this whole wall of Eurotrash. So I went up and they had a new release of [Italian director Sergio Martino’s 1972 film] Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key, this giallo movie based on an Edgar Allan Poe story. So I watched that, and then I started going back, and I rented all these giallo movies, all the Lucio Fulci movies — not so much Argento, but Mario Bava — I went down the list. I was also watching Abel Ferarra movies, and there’s a lot of nods to that in Night Business.

So this stuff was really inspirational to me as far as content goes, and tone. Yeah, I was just really into sex and violence. At a certain point, I was still doing these weird drawings in this book, trying to use them as my illustration portfolio, trying to get jobs doing editorial illustrations. It was this grid-paper sketchbook, like graph paper, and I would not plan anything out, I would just start drawing. It was all stream-of-consciousness drawing, and I wanted the sketchbook to be my portfolio because Stephen Heller, who was the art director at the New York Times Book Review, actually gave me one of my first illustration gigs out of college. That was one of my first experiences as a young illustrator, and he said he didn’t like looking at portfolios from illustrators as much as he liked looking at their sketchbooks. The sketchbooks were more interesting because they were more unconscious mark-making. They weren’t making it for something, just putting down images. And he said that was more interesting to him than looking at these really clean, very beautiful portfolio cases full of all these nice color copies presented in a professional manner.

That hit home for me, so I started making a portfolio out of that sketchbook, that drawing where I would just sort of make stuff up as I went along. It was a huge breakthrough because when I started doing comics I had enough faith in just working with pen, and I had come to kinda like it when I didn’t know quite what the image was going to be until I started putting down the ink. So that was a huge help as far as making Night Business #1.

SENECA: So now you’re finally gonna do your comic. Did the first Night Business issue start out with you thinking, “Okay, I’m gonna sit down and make a comic,” or was it more just kind of seeing what happens?

MARRA: No, it was like, “I’m gonna make this comic.” I only planned out the first five pages, where it’s this stripper getting killed, but then I started to figure out the thumbnails for the rest of the pages. I knew I wanted to make this comic, but I wanted to plan it as little as possible. And I actually had this deal with some interesting people to publish it, so that gave me some incentive.

SENECA: Who was gonna publish it?

MARRA: These guys out in LA called Nerdcore. I don’t really know if they do much publication. They put out a calendar, like a pinup calendar, and they were gonna try to expand into comics, I don’t know. But their interest helped motivate me to complete the issue, and the second issue too.

Oh, I remembered why I started talking about that sketchbook! I had been drawing a lot of more lowbrow stuff in there, I started finally admitting to myself that lowbrow stuff was all I really cared about. It wasn’t about the Rwandan genocide. It wasn’t about trying to create important artwork with important content. It wasn’t about trying to create faux art. I finally accepted these guilty pleasures that had been haunting me all my life as being what I really wanted to do. I didn’t have professors anymore, it was just me. And also being in kind of a depressed state, you’re looking for stuff that can lift you out of it, so I was like, “Fuck this, I’m just gonna draw stuff that makes me happy,” instead of trying to make stuff that I think people want to see, or that people will think is significant.

SENECA: So how long did this first issue take you? Was it a super-big struggle or did it just pop out?

MARRA: Super-big struggle. I mean, the first five pages were a huge struggle and then it started to get progressively easier… and then after I finished it I was like, shocked that I’d finished it. Actually, I lost the first draft of it. I’d penciled it and lettered it, and I left those pages on a train platform, and it was just devastating. For a half hour I was just miserable. And then, you kinda work your way through all the emotions, and I was just like, I’m gonna take a week and not think about it and see what happens. And after a week I started it again, and it was probably better than I originally had done it. I had memorized the whole thing in my head, so I just redrew the whole thing -- didn’t lose it -- and yeah, it just became progressively easier. Every book I’ve done since then has been easier and easier to do, because it’s not unknown, the amount of work that it takes, it becomes part of the process.

SENECA: So was the impetus for starting this ongoing comic, Night Business -- was it more having specific images of a world you wanted to draw, or was there a specific story you wanted to tell?

MARRA: It was definitely more than the story, more of the tone. I wanted to tell a giallo-style story, but I mostly just wanted the stiff dialogue, stiff figures. I didn’t want to worry about impressing anybody with beautiful movement depictions or anything. I was really into this idea of doodling, and that being the finished piece of artwork. It’s almost like acting, like I’m trying to be someone who doesn’t understand what they’re making, and has this sort of naïveté. Very strong convictions about what they’re doing, and no idea about how it’s coming across.

SENECA: So this is the dude on the back covers of all your comics, right?

MARRA: Yeah, it’s almost like I have a character that I do Night Business in. But it’s weird, because that character probably isn’t too far off from who I actually am. Something I think about a lot is how we’re judged as people -- we don’t always know what we’re doing, we do unconscious things, and those are the actions that people judge us on. I’m sure there’s an element of myself that does things unconsciously -- even in my own work -- that I’m not aware of but other people pick up on.

SENECA: Okay, so you make this giallo comic. Did you feel like this was something that was missing from comics?

MARRA: Yeah. It was definitely a reaction to all the comics that I saw. Being in comics, you can’t help but be aware of the impact of stuff like Watchmen and Maus, and I remember around the time that I started discovering Jack Kirby, I was like, “This is what comics should be,” and I hated the fact that we had so many stupid superhero comics trying so hard to be realistic. Trying so hard to be like Watchmen. I hated the grittiness factor, and I think a lot of other people felt that way too. I hated the fact that comics were trying so hard to be something that they aren’t. I hated the fact that comics as a medium wasn't proud of itself. It wasn’t proud of itself, and it still isn’t.It tried so hard to be something that it wasn’t, it tried so hard to be like movies or a TV show. It was not trying to be more like Jack Kirby. And that pissed me off.

SENECA: Did you not see Night Business as a dark, gritty thing?

MARRA: Well, here’s the thing. The other side of the coin was that art comics were trying so hard to be like literature, and I was like, no, that’s not what comics are either! Comics should embrace the idea of being exploitation. Low level, gutter-trash entertainment. That’s what I was trying to make with Night Business. If you’re trying to make a gritty comic, have fun making it as gritty as possible. As nasty and gory and sexy and filled with the most base human emotions as possible. Don’t try and make it reflect come kind of reality, like they do in these superhero books. I don’t give a shit how Superman’s costume works. I don’t care! He’s Superman, that’s all he is. I much prefer those Superman comics from the ‘70s where it’s all bizarre sci-fi stuff. I don’t like when you try and over-explain things. I became really aware of all the exposition in comics -- man, it’s all trash anyway, they should just stop doing it!

So that was that side. If you’re gonna make mainstream comics, make them as fucked up as possible cause nobody gives a shit anyway. Why are you trying so hard to capture an audience that isn’t interested? And the other side was literary comics and art comics that I was so annoyed with for being all this autobiographical sad-sack stuff. Why should I care about your lives? I don’t really care all that much about what a loser you are and why you can’t get chicks. So Night Business was all about power, all about revenge. The main characters don’t have any kind of doubt. Johnny Timothy is just gonna take care of shit, beyond what even the law can do. I also had started watching Charles Bronson movies from the ‘80s, Stallone movies like Cobra and Rambo: First Blood Part 2, Steve McQueen movies, Eastwood movies. There’s a perfectly good American male archetype out there and yet you have all these superheroes crying, all emotional. Why? They’re archetypes, they’re not supposed to be representations of like, my out-of-work uncle. I want them to be the fantasy of what I could possibly be in my dreams, you know?

So that was really frustrating, and that’s kind of where I was coming from with Night Business. It was a reaction to what I was receiving from both mainstream and art comics.

SENECA: So what did you see that was valuable to pull from the mainstream, and from art comics? Because probably more than anyone else, really, you straddle the border between the two.

MARRA: Yeah, it’s pretty funny. Night Business is formatted like mainstream comic, but it’s perceived as an art comic. I like to think of it as like, the anti-art comic, because it’s trying to be mainstream and yet it’s not like any sort of mainstream book. I kept on thinking about Marc Laming and John Stokes, Howard Chaykin…

SENECA: Yeah, American Century.

MARRA: American Century is so badass. It’s got a great 1950s noir tone, it’s a like a James Ellroy style noir. And Harry Kraft, that guy just doesn’t give a shit. He has his own code, and I loved how mean everybody is to each other. It’s such a mean comic. The whole first arc is about the CIA meddling in South American politics, I loved that whole big government fuckin’ around with industry in foreign countries thing, all that espionage. But it’s also a commentary on the illusion of ‘50s middle-class America, and the main character is just this total badass.

SENECA: That dude is like a Hugh Hefner figure. He does the exact same thing that Hef did, he’s like, “Fuck this middle-class family life bullshit, I’m gonna go have adventures.”

MARRA: Yeah! Yeah, I just loved it so much, man. I loved it, literally, I would read it constantly. That was probably the only thing as far as content goes, art goes, that was happening at the time that I really cherished. I thought it was the only comic worth reading. It got, I think, pretty great reviews, but it got cancelled at like issue number 26 or 24 or something.

It was incredible. I think it’s the best comic that came out in that decade. I still look at it and get blown away. I own original art from it, I bought it really cheap, and I think it’s some of the best art I’ve ever seen! Really, really, really amazing. I knew about Chaykin, obviously, how can you not? But Mazzucchelli was a really huge Chaykin fan, going back to American Flagg! and how influential that was. He cited that as probably the most influential comic that nobody talks about. It influenced Dark Knight Returns in so many ways, the little TV set panels, and the way that Chaykin used sound effects. But tonally, how adult it was! I dunno if it influenced Watchmen or not, but American Flagg! is an incredible comic that I don’t think transcends the comics community the same way that Watchmen and Dark Knight do, but it should.

SENECA: Well, if he had done it for a big publisher, I think it would, but it was out of print for 15 years. Speaking of getting full runs of comics for cheap, I got the whole run of that comic for cover price.

MARRA: Also, I don’t think that Chaykin really blabs as much as Frank Miller and Alan Moore, so that might have something to do with why he’s overlooked…

SENECA: Chaykin’s definitely a big blabber though…

MARRA: He talks like a sailor. He’s a pretty badass motherfucker himself. The main character in American Century, I imagine that guy being Howard Chaykin, you know? I think he’s just the best, I’m sure he’s very successful but I wish he’d had even more success because of how great I think his comics are.

SENECA: I remember when people saw Night Business, everyone was saying that this was the fucking Paul Gulacy comic. How conscious were you of that influence?

MARRA: I mean, Gulacy was influential in a similar way to Laming and Stokes. It wasn’t as direct, but one thing I loved about Gulacy was just the attitude that he brought to drawing figures, it was just so intense, the way that he drew. Some of those Master of Kung-Fu issues, it’s the most intense comic book art I’ve ever seen. There’s one of them specifically, number 40, that blows my mind every single time I look at it. It’s the best comic book ever illustrated, in my opinion. I mean, as far as a total body of work goes, Kirby is the best. But this one issue, the emotional intensity that he had when he was drawing, it overrides any mistakes or lack of drawing ability. It’s sort of like Giotto in a way; the emotional intensity he brought to the images is so powerful it makes up for any drawbacks or flaws he might have as an image maker. Gulacy’s stuff is a little off, but it doesn’t matter because he’s just so committed to it. That’s what I wanted Night Business to feel like, one of the Master of Kung-Fu issues that Gulacy drew. It’s stuff he drew when he was probably like 19 or 20, so it kinda has that teenage mentality to it, you can tell it means so much to him even though it’s just this Bruce Lee knockoff comic, you know? It’s just capitalizing on this craze from that time! It doesn’t matter! But to him, it’s everything. And that’s what I wanted. It’s just so intense that you could feel it by looking at it.

But the weird shadows and stuff in Night Business, the weird facial shadowing that doesn’t really make sense, that stuff was all from American Century. That’s kind of what I wanted to do. It’s like how because Giotto didn’t understand perspective, his buildings look off. I wanted the person who drew Night Business to not understand light. He’s like, “I know there has to be some kind of shadow here, so I’m gonna just have to fake it!” Just to sell the idea of noir and shadows, even though it doesn’t make sense at all. I wanted those mistakes to be evident as mistakes, to be visible.

SENECA: Do you get off on the Image Comics dudes now at all, in retrospect?

MARRA: Yeah. I like Marvel Todd McFarlane more than I like Image Todd McFarlane though. I think it happens to a lot of guys. I think his art looks better when it’s on newsprint. I don’t like it on glossy, when you can see every little razor-thin line, and also the coloring is just hideous — it really doesn’t serve his art. But I love looking at the Spider-Man issues he did, because even though it didn’t print as crisply as it did on Image’s glossy paper, there’s something cool where you have to sort of meet it halfway. It’s more the indication of this complex rendering, and then when you can see everything it’s a less active dynamic when you’re reading it. It’s kind of a weird thing to say, but I prefer crappier materials. 'Cause I think comics should be crappy!

SENECA: Ah man, perfect segue!

(Continued)