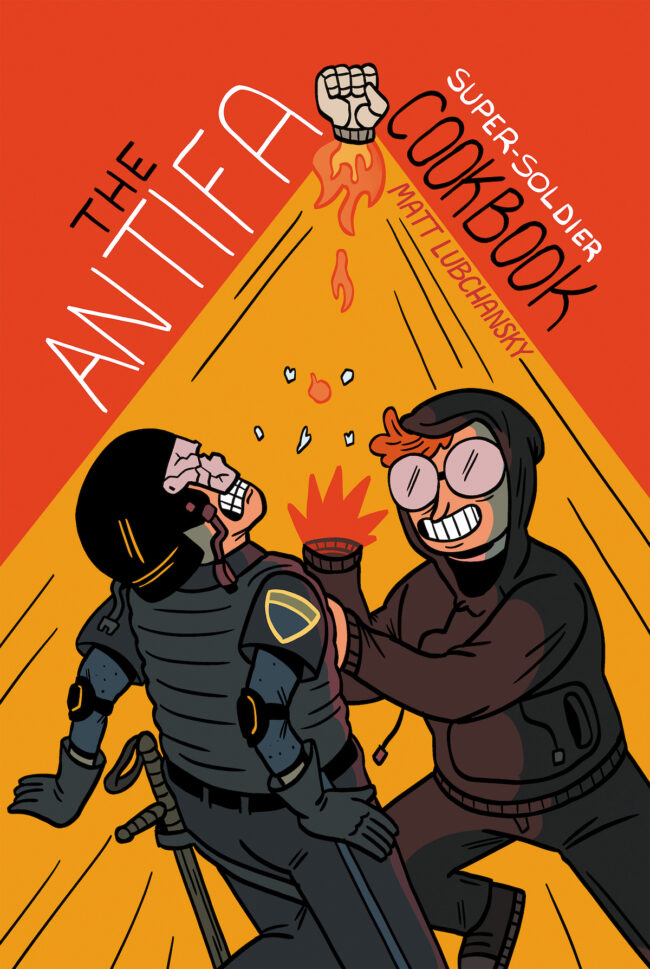

Matt Lubchansky is a political cartoonist, and the person behind the webcomic Please Listen To Me. The Associate Editor at The Nib, Lubchansky was a finalist for the 2020 Herblock Prize, where the judges described their work as “distinguished by a wise diversity of subject matter and a cleverly askew sense of humor.” That cleverly askew sense of humor is present in their comics and in two books coming out this spring. Silver Sprocket is releasing The Antifa Super Soldier Cookbook by Lubchansky, and Abrams is publishing the anthology Flash Forward: An Illustrated Guide to Possible (And Not So Possible) Tomorrows, which Lubchansky co-edited with Rose Eveleth and Sophie Goldstein. Lubchansky and I spoke recently about what they hate to draw, engineering, conspiracy theories, and the relationship between satire and speculative fiction.

Matt Lubchansky is a political cartoonist, and the person behind the webcomic Please Listen To Me. The Associate Editor at The Nib, Lubchansky was a finalist for the 2020 Herblock Prize, where the judges described their work as “distinguished by a wise diversity of subject matter and a cleverly askew sense of humor.” That cleverly askew sense of humor is present in their comics and in two books coming out this spring. Silver Sprocket is releasing The Antifa Super Soldier Cookbook by Lubchansky, and Abrams is publishing the anthology Flash Forward: An Illustrated Guide to Possible (And Not So Possible) Tomorrows, which Lubchansky co-edited with Rose Eveleth and Sophie Goldstein. Lubchansky and I spoke recently about what they hate to draw, engineering, conspiracy theories, and the relationship between satire and speculative fiction.

Tell me about The Antifa Super Soldier Cookbook.

Last year in the late summer Avi at Silver Sprocket contacted me. I’ve known them just through comics and wanted to do something for them for a while. It was right after that older man at a protest in Buffalo was hit by the cops. That video was going around and people were saying that he had thrown himself to the ground. It was so patently ridiculous on its face but Avi said, what if there was an actual super soldier program to make old men fall to the ground? It went from there. We talked about it and I wrote a script and drew it in the next few months. I started thinking of it as the Inspector Gadget version of Antifa. It’s sort of a continuation of a couple of strips I did for The Nib starting a couple years. One was an audition for crisis actors. I did another one about a job interview to become a paid protestor. The third one was there was a scare that Antifa was sending busloads of people into rural America to burn down small towns for BLM for some reason. I did a comic strip about the bus depot. That’s the prototype of the character in the book. It’s taking these insane conspiracies at complete face value and racheting it upon a smidgen to make it look as ridiculous as it sounds to anybody who’s ever spent more than five minutes outside of their house, or has ever gone to a protest, or ever spent time in activist spaces at all.

I wasn’t uninvolved previously, but I’ve gotten more involved in activist spaces in the last year with a group that I’m still doing a lot of work with. As I spent more and more time in activist spaces, the more ridiculous it sounds. I always like thinking about the imprecise way that conservatives are talking. They can’t understand the difference between a soft liberal, a communist, and an anarchist. All these very serious distinctions and divides. Oh, they’re all communists! Which is always funny to me. Like at the capital there are people calling them anarchists, which is the funniest shit in the world. If they were anarchists they would have milled around outside for six weeks trying to get consensus! They would have had a committee to form a committee! I’ve been in groups that are leaderless. Also the info sec would be better. They wouldn’t be streaming live video of their faces saying, I’m in the capital! So in the book I tried to get in as many of these insane tropes, which are pretty ridiculous on their face, and build a whole world out of all these contradictory things that people say in the hope that it comes off as ridiculous as it sounds to me.

You’ve always been good about taking these crazed conspiracies and then breaking them down, going, here’s how this would have to work. And if you don’t think you’re insane by the end, well…

I am, at my worst, a little conspiratorial minded. I have always been drawn to conspiracy theories as a topic of interest. As a child I used to check out a lot of books about cryptozoology. I have a tattoo of Bigfoot. On some level it’s, there but for the grace of god go I. It’s always been very fascinating to me. How and why people believe these things about their ideological enemies.

Conspiracy theories used to belong more to the left wing and now conspiracy theories and “truthers” are very far right.

I think it’s interesting. Seventies and eighties paranoia are an obvious outgrowth of Watergate and the Vietnam War. In the 90s you have the government as this all powerful thing that can pull off this huge conspiracy without anyone finding out. I think we learned when the Bill Clinton impeachment broke and all that with all the information that leaked out that you could not keep aliens a secret! I’m sorry! I was watching Independence Day and it was mind boggling. They kept all this from the President? My ass. That reached its zenith in the 90s. 9/11 shattered a lot of the idea of the impermeability of the government.

If you’re talking about Antifa versus the police, that’s a clear projection of people who are petty fascists, Trump’s richer base, who are doing a classic transference of accusing their opponents of what they actually do. I actually had a note in the back about all the things that the cops in the book actually do. And I encourage people to read more about this. They’re accusing the left, Antifa, whatever, of being this all powerful force that can do anything they want – because cops can do whatever they want! There’s qualified immunity, racism, I could go on. We know this. The cops have all this power. They have tanks. I have watched so many cops run people over in my town and nothing happens to any of them. The only scenario that would make it okay for the cops have all that power is if they were in a power struggle with George Soros’ Antifa drop soldiers. That’s the only plausible explanation for these people.

In your book, the cops are doing what they do. They don’t do anything that hasn’t happened countless times. That’s very realistic. Meanwhile Antifa is ratcheted up past 11 with secret headquarters and it was a lot of fun.

There’s also a heavy dose of Robocop in there, which is an obvious thing to think about because he’s a robot man who fights crime. Verhoeven is such a great satirist of America. It’s a heightened reality where everything is horrible, but here are people making it worse still. I think where we are currently is a very Verhoeven future in some regard. Like on the show The Masked Singer. Or The Masked Dancer? You know they’re going to have C list celebrities. The other day they revealed one and it was Elizabeth Smart! The kidnapping victim. I mean, what a thing you would see on TV in Robocop. On a long enough timeline I guess capitalism just satirizes itself. Those are the vibes I was going for.

This is a longer narrative than you’re used to making. What has it been like and what has the process of making a longform comic been like?

That was the biggest challenge of the book. How do you make satire interesting for more than a couple of pages? Originally my pitch was 150 pages, but I thought it would be boring by then. You have to keep it short and sweet. I put in a lot of action sequences. I tried to put in I guess some eye candy so its not just satire. My work that’s been published is all short form work, but I’ve been working on long form things in the background. I’ve been working on book pitches and I wrote an entire graphic novel that has not been drawn. It's been on my mind for years that I want to start doing more long form work and this was a good opportunity to stretch my legs. And to tell a fictional story. That’s something that I’ve been trying to do more of in my work. I have another book coming out this spring that I did a 15 page chapter for, Flash Forward, that I also edited with Rose [Eveleth] and Sophie [Goldstein]. It wasn’t my first time making a short story, but I immersed myself for a year and a half in that world. So I’ve been working my way up to something longer for a while and it’s nice to be there now. The next goal is to do a full length book that is not necessarily all satire. This could have been stretched to a full length book, but it would have been a completely different story. There’s no real conflict here. I make my point and I make my jokes. I’m really proud how this book came out.

You mentioned Flash Forward and co-editing that book is a very different experience from the editing you’ve done at The Nib.

Most of the editing I’ve done at The Nib is the strips section. I’ve been doing Dispatches here and there, which are two page personal comics. Generally I’ll work on the ones that are funny. I don’t have the research background that the other editors like Andy [Warner] and Sarah [Mirk] and Whit [Taylor] and Eleri [Harris] have. They handle the heftier stuff. I’m used to editing and working with people, so the mode of working with people on fiction took some getting used to, but it’s the same kind of process. It was really rewarding and when it came time to do my story, it made me a lot better. Working on this book made me a better cartoonist, too, because a lot of it was I’m thinking about how an editor would look at this. What kinds of holes in the story I would see as an editor. I think everybody should be edited. It’s good for your work. In comics, outside of very long form work, there’s very little editing, but I think most people could benefit greatly.

On Flash Forward, you’re working on a different kind of story and editing differently and working with two other editors each of whom have different strengths and backgrounds.

I think jumping from satire to speculative fiction is a pretty natural direction to move because it does a lot of the same things with different tools. The story I did in Flash Forward has a couple of jokes, but not many. It’s got a point and uses the plot to make that point. It does a lot of the same thing I’d be doing if I made a satirical story, but processed differently. It’s sadder more than funny. Because its hard for me to see a future in which things are good. That’s my own problem. So when I’m given a prompt like Flash Forward, what if X happens in the future, my first main thought is how will the capitalist class use this to exacerbate what already exists? It’s hard to separate myself from that world right now. I don’t think it’s that far from doing satirical work. I’m interpolating instead of exaggerating.

You went to school for engineering and I wonder if that approach and that way of thinking and problem solving has played a role in your work?

I was a pretty garbage engineer, so it’s tough to say. I was not good at it. I would say that it prepared me for the grind of cartooning. If there is a problem, engineering programs your brain to not despair. There is a solution, you just have to find it. It put me in that mode for the rest of my life. Which is in some ways good and some ways bad. I think it’s really helpful with comics. If anything, having a background in doing a lot of drafting is helpful for my visual imagination. I would also say that it made me good at spreadsheets. Before I made myself wash out, I was a project manager for construction work and the best thing it gave me was the organizational skills to keep my life together and hit deadlines. Which I know is a big problem for a lot of folks. I have a reputation of being reliable, which is helpful. For working on a book, it forces me to break things down into doable components and build it up that way instead of wondering what I’m supposed to do, I suppose.

I know some engineers and they found it freeing that it’s about solving a problem. Not, there’s one answer and one way to arrive at it. Instead it's about discovering the process and solution and the possibilities of that.

For sure. You want to turn the light on in your room, you could walk over and turn it on or you could build a trebuchet. In that regard it rewards creative thinking on the abstract level. What I found is that in the professional world, they don’t really give a shit. There was no creative thinking. They give you a tool belt and you choose which to use. And drawing ductwork is very boring. I did an interview with Current Affairs and they asked me about which shapes I like to draw. Which is a great question. I said, I’ve drawn enough straight lines by this point in my life. I drew a lot of straight lines the first twenty five years of my life and I don’t have to draw a straight line ever again.

Having finished the book, what did you take away from it? What have you taken away from these longer narratives?

I feel like I’m a better storyteller now than when I started the process. So much of comics is craft and not necessarily art. Comics are the rare thing that is both. I think a lot of comics is just honing your tools and getting the hours in. There’s fucking Malcolm Gladwell's 10,000 hours bit, which is horseshit on so many levels, but might be true for comics. It’s pages. You have to get a number of pages in. The more pages you write, the better you write. The more pages you draw, the better you draw. That is pretty straight up I feel like. The next long thing that I write I know what things that won’t be in the first draft, mistakes I made early on in this process, storytelling issues someone had to tell me I was doing wrong. I just want to keep doing it.

It’s not like everything has to be a path, but I do love speculative fiction and genre fiction that has a speculative or political bent. The stuff I’ve been doing lately is more in that vein. I want to do more longer stories that are just stories and less playing with action figures to make a point, which this book sort of is. I want to entertain people. I’d love to do more longer traditional novel length stuff. I’m never going to make work that’s not political. That’s just not possible. People who say their work is nonpolitical are lying or have bad politics.