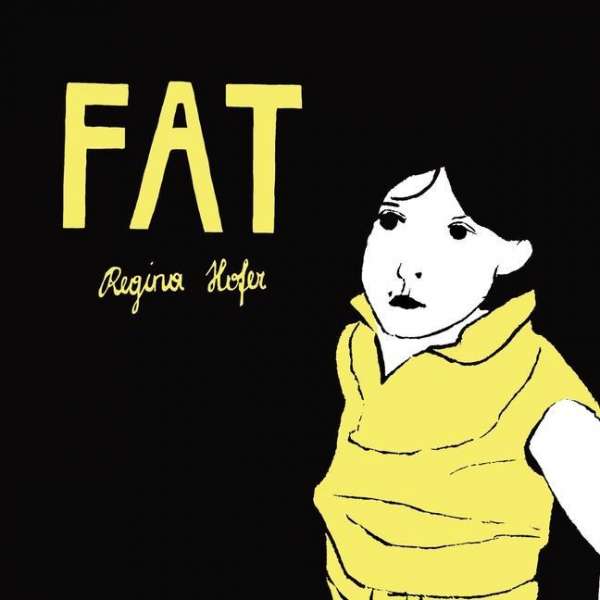

The English-language release of Regina Hofer's longform debut Fat via Graphic Mundi, an imprint of Penn State University Press, marks the by-now third version of a work elucidating one young woman's struggle with eating disorders.

Its earliest incarnation back in 2008, still a skinny offspring from a then-not fully fed tale, raised its hungry mouth in the anthology Perpetuum (Latin for 'perpetual'), where an impressive number of the Austrian dessinatrice's compatriots were presented. At that time, Hofer was publishing under her nom de plum -- or more fittingly, *guerre* -- Borretsch (likely reasons to be found here).

Perpetuum remains a well-curated, voluminous, and therefore still-recommendable collection, providing readers with an overview of the Austrian comics scene during the first decade of the 2000s, simultaneously featuring a bunch of women - among them the female future-spreading mind of Spacelove creator Michaela Konrad.

Generally, publishing options for comics are rare in Austria, especially if you're sailing besides the mainstream, and you belong to a minority. That's why you're most likely to discover the likes of Konrad dangling between science and fiction in rather unusual places, like galleries, or art shows held at museums. Hofer's and Konrad's landlocked motherland not even getting a mention in the Wikipedia entry for "European comics" can be taken as further evidence, but hey: there's still the honorable and bilingual (German/English) independent comics magazine Tonto. But then, not so much else.

So in Perpetuum, by placing the first chapter of Blad (standing for *fat* in Austrian) not far from a story like "Sagn ma" ('tell me', but also 'mention' or 'let's say', ambiguities intentional) by "Verena W." (former Tonto contributor Verena Weißenböck), synergies rose out of the accrual of tales showing miseries repeatedly caused and carried out by those of age, wealth or power against the weak and unprotected. Hofer's autobiographical main character is constantly assaulted by her environment, wherein toxic masculinity and other outgrowths of an unbalanced gender ratio are firmly established. At first, this behavior is mainly attached to her deer-hunting father, who's depicted several times sporting the abbreviation RUR written all over his chest – an allusion to Karel Čapek's famous science fiction play R.U.R., wherein the term 'robot' gets introduced to the world.

Hand-in-hand with such business-related routines as enduring self-optimization is a lean management: like the imagery of a vanishing point, where your individuality doesn't matter anymore, supplemented by an unwillingness to be outspoken about your feelings. The future as an escape pod plays another significant role on the page: rudimentary shapes presented as space ships, probably to take you away, are placed underneath large letters desperately roaring out SCIENCE FICTION, as in 'possibility of a future' – which is incredibly sad if you think about it.

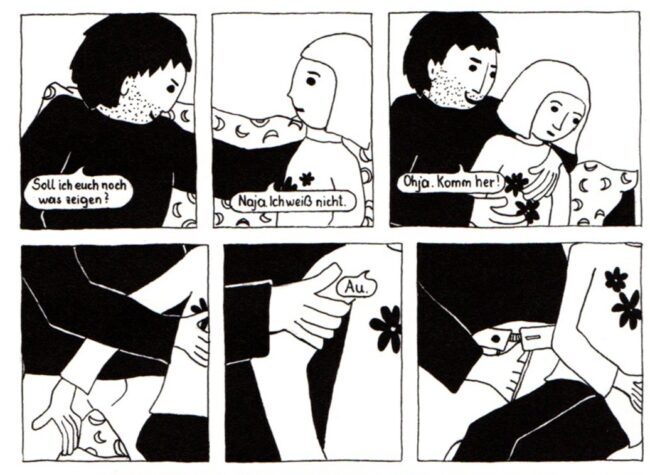

Not enlarged, but reduced to smallness and helplessness, are Verena W.'s little girls in "Sagn ma", when forced to perform and endure sexual acts on and by an ominous uncle. His misdeeds are covered by a sense of family cohesion gone horribly wrong, and a deafening silence. Verena W.'s all-too-fitting depiction of such acts in a black-and-white style reminiscent of children's drawings makes you feel fed up when following this depressing scenario, but also saves it from becoming child pornography because of the abstraction applied on NSFW content; in the meantime, Hofer's piece feeds her own fears by fueling a seemingly endless ride on a merry-go-round with overeating and regurgitation. The scenario is mostly depicted using symbol-like figures in front of compositions sharply cut out of negative spaces with no room left for any greyscales. How could there be room - when you can't stomach any more stuff, because you've already housed all the fear neighboring to major uncertainties?

Some lesser details in Blad's first chapter were altered in the later-released full German version: a minor character never depicted in person, Hofer's elder brother Martin, who died from an atrial septal defect a few days after the narrator's own birth, is no longer mentioned by his name. This was probably a choice due to the text's rhythm; other alterations -- especially those where peculiarities from Austrian-German have been changed to standard German ones -- are implemented to make the story a tad more accessible, apparently in other German-speaking regions, including godforsaken tracts of land like Italy's subdivision South Tyrol, or Switzerland. This procedure is repeated in the English translation, where several names of localities like Münzbach and Golling an der Salzach undergo alterations for the sake of simpler attributions as “upper Austria” or “river”. But even before translation to English, the text's cadences were slightly modified by the abandonment of ellipses; furthermore, the opening splash was stripped of its framework by blowing it up and dropping the dessinatrice's alias, previously integrated in the page composition. For the English version, Hofer then re-lettered things like handwritten shopping lists and several translated soundwords, if onomatopoeically inappropriate; for example, *ZACK ZACK* -- commonly known as a name given to some Anglo-Americans, but used as an imperative command in German -- had to step aside for a more profane version featured on an announcement poster for Hofer's first exhibition. (The poster also marks Hofer's chance to run free from the parental household towards autonomy.) A t-shirt featuring the printed slogan “Lick me all over 20 $” though, remains as it was – in its English original. At one point, translator Natascha Hoffmeyer replaces Hofer's use of the word taxieren, which bears resemblance to the English term 'taxes' and means to determine the worth of a person, so that the subtle theme of the worth of a person -- especially a female one -- gets slightly lost. But Hoffmeyer's interpretation is very close to the original; and, as you should know, things can get lost in translation. Still, I'm glad they didn't change the title Blad in Germany, because it's the kind of title which makes you curious, paired with an interest-arousing cover – and I'm convinced that would've been possible for the English edition too.

But stepping away from foreign tongues not always easily transferable to the universal language of narrative rhythms: there are few who command those panel beats like Hofer does, her art amenable to tonal sequences not always easy to follow, but providing readers with reliable unease in seeing things in her drawings that cannot be unseen after recognizing their true meanings. That characteristic quality goes even further in her follow up book, Insekten, a collaboration with Austrian cartoonist Leopold Maurer.

Insekten is based on an interview with Maurer's grandfather, a former member of the Waffen-SS, who -- still full of pride, and thus without making any use of dissimulatory tactics -- tells about the horrible crimes committed by Nazis like him during World War II. And as before in Fat, Hofer's insurmountable inclination toward creating vague content open to association elevates this oral history, which otherwise easily could have become your usual mediocre history drama looking for approval. Hofer's equally talented counterpart, Maurer, has a less symbolic, but nonetheless impressive drawing style on par with the dessinatrice's idiosyncrasies, read as: a sometimes vivid expressively linework; and a way of displaying only details as a means of depicting a bigger picture, which complements Hofer's interpretative content well.

It's interesting to see how all these comics are deeply rooted in misguided communication, where the words are absent by which to name actual conditions, so the pictures and abstractions have to jump to the rescue like an emergency room for opening up spaces to all the emetic things the protagonists are unfit to digest. As registered nurse MK Czerwiec wrote in "Graphic Medicine", appearing in The Comics Journal #305 (its subhead Health Care, Disability, Illness & Comics): “Nurses see a lot of things going wrong in health care, and I'm not referring to clinical error; I'm referring to errors in communication. The kinds of comics I'm describing are a first step towards deepening empathy, to begin to bridge those often-wide chasms between family members, patients and care-providers, communities, as well as persons and the society in which they live and depend on for their care.” The efficacy of such works vary; for example, a genre-driven comic rooted in horror set pieces like The Replacer does very well (though its retro VHS-style cover conception has reached the status of a generic drug pushed onto the market via an anemic competition, freed of paying any licensing fees), while another, The Tenderness of Stones, by its hackneyed ideas borrowed from comics mainly considered artful a la Olivier Schrauwen, fails grandiosely at the same conceptual formulation of building bridges and stripping off the leaves from the overgrown tree of misrouted social commitment. US-American Roz Chast and Dutch Judith Vanistendael both share a pretty similar background, but use a very differing approach. Chast, like Marion Fayolle or Zac Thompson, was personally affected by severe diseases in her family, but managed to keep her head up in Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant? by fancying a warm sense of humor - speaking through bright colors of the ordeal that was the path of her parents into vascular dementia. In contrast, When David Lost His Voice, Vanistendael's comic about larynx cancer, utilizes muted watercolors to keep things in flow and to create a language for those losing their voices, showing a mastery usually witnessed if following dessinatrices floating similar boats like Aidan Koch or Catherine Meurisse.

So what counts is an artistic approach of wholeheartedness, as opposed to throwing around topics presumed to be *touching* or *moving* and desperately trying to raise a cheer. Such is an illness which a majority of those comics ashamed to call themselves comics suffer from - to say nothing of their artists, who just appear to be incommunicable.