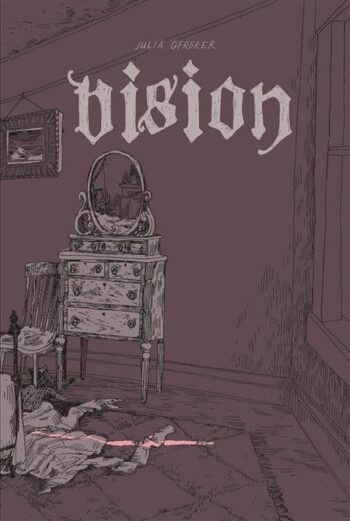

Cartoonist Julia Gfrorer's new graphic novel, Vision, is a gothic nightmare of jealousy, repression, and sexual need. We sat down to talk it over in a cabin on the Maine coast as, fittingly, lightning flashed over the bay and rain beat against the windows. - Gretchen Felker-Martin

Gretchen Felker-Martin: So, I loved this book. It’s extremely beautiful. I’ve been reading your work for a long time now and I felt like this brought together things I’ve seen you do before in a way I wasn’t expecting. One thing that really stood out to me: in Dark Age, which you wrote like four or five years ago, the climactic image is the shadowed silhouette of this shaman. And it reduces the main character to hysterics. He collapses.

Julia Gfrörer: Yeah, he flips out like that guy behind the Winkie’s in Mulholland Drive. I mean, literally like that.

And this is the second time that you’ve had this kind of idealized masculine, shadowy figure in some sort of important position within your book.

Hmm. Do you want me to tell you about that?

I would love to hear more about that.

I think a lot about masculinity. I think that’s probably obvious from my work. And I talk about it in my work in ways that sometimes seem to make men uncomfortable. Sometimes they’ll want to talk to me about it and fill me in on some aspects of the male experience that I might not have picked up by them dominating every aspect of culture for the last 40 years of life. There’s stuff I might’ve missed. In reviews a lot of times there’s a focus on “Julia likes to write about men who are weak, and there’s a lot of crying men.” That’s true, I guess, but I think they feel subjected to a gaze in a way that they don’t normally experience. In spite of absorbing all this cultural information about what it’s like to be a man, I’m looking at it as an outsider trying to make sense of what is different from me about these people. And why is it so hard to relate to them? I mean, it’s kind of a prosaic idea, really. But there’s an ideal of masculinity that’s like strength, power, the ability to affect the world around you. That’s the essence of masculinity as we understand it, right?

Right.

But that’s an archetype. It’s an ideal. It doesn’t exist in reality. And men struggle with orienting themselves to it, and I think are troubled and even traumatized by their inability to live up to that.

I think you’re right about that.

I think you’d know better than me.

I was gonna say, in fact I know you’re right about that, because I used to be one.

So, it’s like this black hole that our interactions are orbiting around. That you can’t see it, but it’s exerting this physical pressure.

And that you actually make that literal.

And that you actually make that literal.

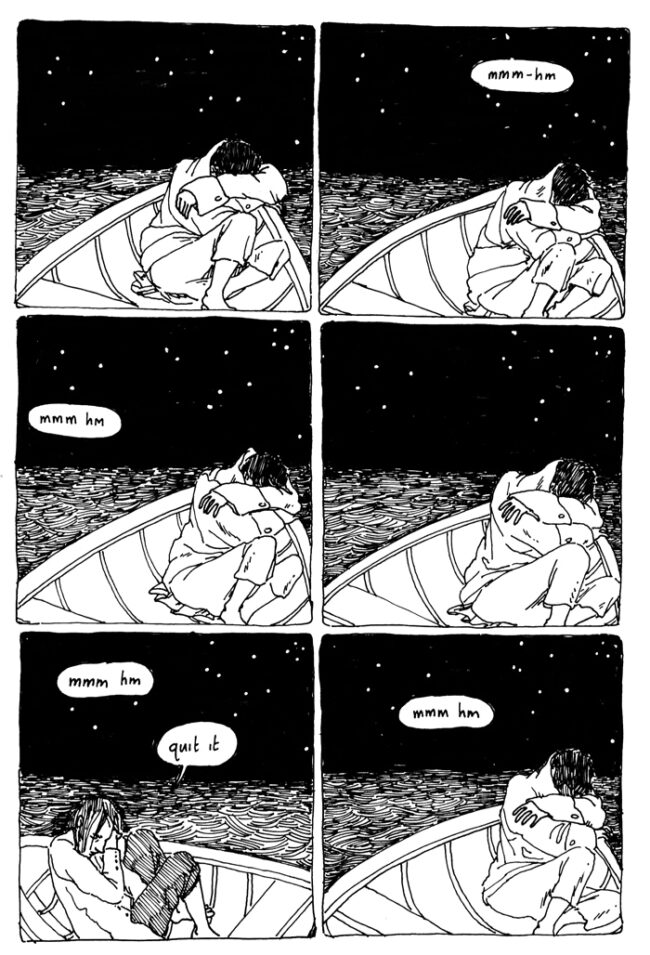

In Dark Age, it’s not totally clear whether the shaman’s really there or not. The idea is partly that there’s two very young people having their first love affair, and they explore this cave together. It’s full of wonders and things that they feel that nobody has ever discovered before. And then eventually they get lost and one of them has to go for help, kind of bringing these adults in to help them navigate this space that had been sacred and private. And it’s a traumatic experience, especially for the boy who gets left behind in the dark.

And he’s the more insecure and needy of the two.

That’s true. So, the shaman could indeed be showing up to help, but it is also the apparition of manhood that by having this experience, by getting lost in this cave, the boy is aware of himself falling short of. And that fear is the source of the insecurity you see in him in the comic, and also just other weird types of aggression that teenage boys have, feeling that they need to prove something. Like they have this spirit in them that needs to be expressed in order to make contact with that masculine ideal. And it’s not super subtle. He’s got these big antlers poking out into the sky. He’s a very virile figure.

That’s something that I find refreshing and powerful in your work. That you’re not interested in occluding your images.

That’s true. I think that you can trust your reader to understand symbols on an intuitive level. I don’t think of it like I’m putting it in code. It’s not a rebus, like you have to pick it apart and figure it out. You just have a sense that antlers are associated with masculinity. In the last couple of weeks I’ve come to the part of Hannibal where there’s an antler man, and I was like, “OK, that’s a thing I didn’t invent.” [Laughter.] Which is very unfair.

It is unfair.

I hate it when that happens. It happens often.

It’s like one of the first episodes of Mad Men, Pete, who’s a very whiny, inadequate character, is being chastised at work and he shouts that he invented direct marketing. [Gfrörer laughs.] Except that someone else came up with it first, but he had the idea independently.

Oh, awesome.

So, there’s precedent.

It’s frustrating when that happens. Well, I’m so in tune with the zeitgeist. I’m kind of a bellwether. When you encounter something in my work you can be assured that it is going to catch fire in popular culture very soon. In a popular culture that is in no way aware of my work. But just that I’m also attuned to the quiet tides of feeling.

You’ve got your finger on the ley line.

Yes, I do.

So, to bring us back around to Vision—

Yeah, the masculine figure in Vision is a little different. For most of the comic, he doesn’t actually exert force in the world. He’s entirely a figure of idea, non-corporeal. And the way that he exerts influence is that he’s only a voice. You just see ... something.

Just sort of a blur in the mirror.

It’s sort of person-shaped, but it’s not clear. You can’t even be sure that it is a person. But Eleanor seems to know him; he’s a person to her. And the power that he has over her is still taking the place in her life of that masculine kind of power — in the absence of other people being willing to take charge of a situation that’s obviously out of control. He’s the only character that’s providing clear, precise direction, specific observations — he’s creating her reality by naming it. So, in spite of not being physically present, he’s a source of stability for her.

It’s clear from the way that you draw her emoting and from the way that you write that this is an oasis in her life. But when she tries to reach out and touch it, it’s ultimately worse than insubstantial. When he does start to affect the story, he’s petty and controlling and violent. Her attempt to make a real connection with someone she can touch and who can return that touch totally ruins her life, because of her connection with this unattainable image.

That’s a good point. I hadn’t thought of it in exactly that way. But that ideal is totally poisonous. Not just for men but for women also, because you learn to expect a certain type of dominance, initiative, some kind of idea about what’s going on.

You start locking yourself into rooms.

You start locking yourself into rooms.

Uh-huh. You start expecting that from the men around you.

Of course.

I mean, so much of heterosexual culture is about fetishizing that.

It’s like the endgame of your personal life, to find something completely and totally fixed and stable with your heterosexual partner. And not only are the pieces that comprise that dream basically nonexistent, but the dream itself is nothing.

It’s weird, right? I got married when I was 26, which is 11 and a half years ago, I think. I think my ex-husband was only the second man that I had ever lived with. To me, cohabitating with a boyfriend was more or less identical to being married, so I thought. But the way that people treat you when you have a straight marriage with a baby, it’s like you’re a whole other class of person. It’s like previously you were a rook and now you’re a queen. And I can’t tell you anything specific, but like when you get together with your family they treat you like an adult, which I was totally not expecting. I thought that I was an adult to them. I was an adult to myself since I was like 12.

Right, but you had entered their idea of what an adult should be.

And even though I think that’s perverse, in a way I understand it. Because as a parent, you dedicate so much energy to this project of producing a person. And you need to feel that that person is settled. You need to know that they have a stable situation of their own so that you can feel like your job is complete.

That’s another thing I see over and over again in your work, this struggle to provide for someone and create stability. To cultivate normalcy.

Mmhmm.

That’s something that’s missing from a lot of stories. And that also brings me to another point, which is: As in depth as you get with masculinity as an ideal, and about the forms that masculine violence takes, I also found that this book was really insightful about more typically feminine forms of violence. The character of Cora, the sister-in-law, who Eleanor has to take care of, not only berates and accuses and abuses Eleanor, but she forces her into intimacy with her through the act of caretaking.

And her forcing this sense of intimacy with Eleanor is also a form of violence. The way that she’ll be friendly with her and act like she cares about her. Like she says, “Oh, you seem like you’re really tired.” And then she flips that into an attack. First of all, I love that kind of interpersonal violence that is covert.

Deniable.

It’s passive aggression. That’s so interesting to me. I have given a lot of thought as to how to handle that with people.

That’s actually something you’ve made me much better at and more aware of.

I have definitely dedicated a lot of energy to being aware of those tides that move underneath the conversation. The way that what people say is often two or three steps removed from what they mean. And if you guess the wrong level of meaning you can get suckered into some really fruitless and painful shit. And those are skills that I had to learn to survive, but then I’m not always able to turn them off.

They shape the way that you experience the world.

And it just makes me extremely suspicious and distrustful of strangers. Not so much friends, but everyone else. But I’m very quick to take offense. Twitter is a good outlet for this, because it really doesn’t matter if you’re a huge asshole to somebody who didn’t mean any harm. If people offer themselves for me to sharpen my teeth on, I think they get what’s coming to them.

They really only have themselves to blame.

Strangers, especially men or people who have profiles that might give someone the impression that they’re men, should know not to take their chances with me. I have no benefit of the doubt to extend to them. And that’s sad, I guess. That’s what people will say. That’s what nice young men who mean well will say: “Well, it’s really sad that you’ve learned to be so distrustful of the world.”

Oh, what a crock of shit.

It’s so fucking lame.

Once you’ve interacted with ten of these people, you know how every last one of your future interactions with functionally identical people will go.

They think that they have something new to say to you. They have no idea that—

—every one of them is Chuck Flanksteak, Protagonist of Reality.

There was some trans woman on Twitter who had a thread about that, and one of the things that she said was that when she started passing when men would talk to her they would kind of automatically assume that they were the protagonist of whatever conversation was happening.

Oh, for sure. That’s something I’ve been through too.

That’s amazing. I can’t imagine what it’s like to talk to men if they don’t do that. What do they have to say?

Well, sadly, almost nothing. My impression of men, having grown up among them and been treated as one for 20 odd years, is that mostly they just play Halo and make rape jokes. [Gfrörer laughs.] I’m not wild about it.

Some of them are philosophy majors.

Even worse. It’s like a chimp with a machine gun.

An undergraduate degree in philosophy I feel like is one of the biggest red flags that you can have. And I say this as someone who’s not not interested in philosophy. Have you read my comic River of Tears? The one where the guy gets a bunch of text messages?

Yes, I have.

So, there’s a girl that he talks to at a party. This is one of my few self-insert characters. It’s clearly me — she’s got long, fair hair and she’s freckled and she’s slouching around at a party talking about semiotics. And he’s like, “I don’t know what that is.” And she’s like, “OK, so just like take a triangle.” And he’s like, “Oh, sorry, I have to take this call.” I’m totally that asshole. I know this. At the moment I can’t think of a way to distinguish myself from other philosophy assholes, but I’m sure there’s some distinction that’s essential.

Here’s my take, as someone who’s known you for a while now. My take is that your fundamental motivating emotion here is curiosity. I know you love to explain things to people.

My favorite! The best thing about being a parent.

But you’re not out to bludgeon them. You’re not out to win.

I might be.

I think you incidentally win a lot. [Gfrörer laughs.] Because you know a great deal. And you’re very well spoken. And you’re charismatic, you have a lot of energy in person.

And I think, maybe more to the point — at least this is an online skill — is I know when to opt out. And this is dirty tricks, honestly. I learned this from doing flame wars on Usenet in the ‘90s. And I’ve had people do this to me in person, so I know how shitty it is. But if you can be the person who steps outside of the conversation and says, “You’re so stupid for even trying to talk to me about this,” it makes it very difficult for the other person to say anything useful or effective after that. Much in the same way that if you tell someone to stop talking to you, anything that they say after that is automatically offensive.

It looks ridiculous.

It’s very bad. And they just shrivel into a corncob. It’s nasty, it’s very bad faith arguing. But again, internet strangers don’t deserve good faith. They have to prove themselves. That’s just the way it is. I have people who I follow that I look up to that don’t follow me back, and I get up in their mentions and try to make them like me. I’m not unwilling to participate in the economy of trying to prove that you might be worth talking to. I understand that when somebody is very popular you have to distinguish yourself before they can be bothered to look at you.

But as the man said, “If you come at the king, you had best come correct.”

Exactly.

And so many of them have not yet sighted correct from the crow’s nest.

And I’ll give somebody like one or two chances. But if they insist on being obnoxious, then I’ll mute them. And then I’ll forget that I did that, since I don’t follow them back, and then they never get another chance. Which is... I was gonna say it’s sad, but it’s actually a net good I think. They’re happy, because they don’t know, and I’m happy, because I don’t have to think about them ever again.

You’re taking all the tension out of the situation.

Yeah, a kill file is a great thing.

I don’t actually know what that is.

This is a Usenet thing also. A kill file just means that you have a list of people who you automatically do not see their messages. They don’t know, unless you tell them they’re in it. So, it’s the same as muting. Before we had blocking, this is what we did. And like muting somebody, it can be... I think Matthew Perpetua tweeted about this recently, like, “I’ll block somebody just for the serotonin.” [Laughter.] If they give me a reason. It feels great to drop somebody in the kill file. It’s like dropping them into an oubliette.

They might as well never have existed.

And you only ever see them if somebody that you wanted to talk to quoted them. Which, when I was on Usenet, I had to do by hand. Imagine that, quoting people by hand.

Goodness, that’s a lot of work. I don’t think I would do that now.

It’s like when you’re playing The Oregon Trail and you do the “grueling pace” or whatever.

So, circling back around within the topic of disposable interactions, a lot of your books are almost literally about being human garbage. [Gfrörer laughs.]

That was my jokey summary of Laid Waste. Have you seen that?

Yes, I have. But in Black Is the Color—

They literally throw him in the trash.

Right, they throw him over into a lifeboat because they don’t have enough rations on the ship. And in Laid Waste, the characters are these people who have been left adrift by the plague.

Right, they throw him over into a lifeboat because they don’t have enough rations on the ship. And in Laid Waste, the characters are these people who have been left adrift by the plague.

Literally waiting around to die. Except for Agnès, who can’t die, apparently.

Well, good for her.

Good for her!

She’ll survive to hang out with the cockroaches. And in Vision, Eleanor, who has lost her fiancé—

She kind of has no purpose now.

She’s this supernumerary person.

That’s a good way to put it.

She just hangs around this house—

—and they just find stuff for her to do.

Right. And the people around her really turn her into an external organ for whatever they need. To Cora, she’s this mama bird, this regurgitator who cares for her.

Well, Cora forces her into almost a parent role. And so does Robert, eventually.

Right. That brings me to the sex in this book, which I think is tremendously good.

Thank you. We’re not going to talk about the human garbage part? You were in the beginning of a question. We’ll get back to the sex.

Right, we’ll get back to the sex. Let’s talk more about human garbage.

Yay! [Laughter.] I mean, six of one...

This is something that’s near and dear to both of our hearts.

The thing about human garbage is a feeling that is especially poignant to our generation. You and I are both millennials, right?

Yeah.

I’m definitely within millennial, but I relate to a lot of Gen X culture. I was born in ‘82, and millennial starts at ‘80, but I absorbed a lot of the cultural influence of Gen X and oftentimes cultural markers of Gen X resonate better with me. Maybe this is the case with Gen X too. Because we don’t have access to those cultural markers that make you an entire person in society, you do kind of have a sense that you’re extra, that you’re disposable. You live in your parents’ basement and whatever.

We don’t have money, a lot of us can’t or don’t have kids.

You can’t have a regular job. You don’t have your own place to live. There’s the sense of being kind of — here’s a Gen X reference — a hacky sack that you’re struggling to keep in the air.

This is something I really admire about all of your work, that nothing is ever fair. These are such deeply unjust, miserable worlds, and these people go through things that are so punishing. And there’s never any suggestion that it could’ve been different.

Yeah, you couldn’t have done anything better that would make this not happen.

Maybe some theoretical saint could’ve made all the right decisions, but not someone actually raised in that situation. Not someone who’s gonna absorb the world around them.

I mean, I’m just not interested in that. I’m not interested in people doing the right thing or making the best, reasoned decision. Because people don’t do that.

You make, like, easy decisions or horny decisions or self-destructive decisions.

You make the decision that’s from your gut. I mean, if you sit around trying to figure out what the right decision is, then nothing ever gets done. Also, the world is moving ahead, whether you participate or not. So, you have to do something.

I think I’ve heard you say that the bread has to get made.

Mmhmm. The babies still need to get fed, the cows have to be milked.

You don’t have the option to sit and figure yourself out.

Right. I was gonna say something about parenting, but I think I would rather not. It’s a subject I avoid in interviews generally.

I can imagine it’s pretty sensitive.

Well, I don’t want to start getting invited to the panels about “Parenting as a Freelancer” or something. Did we have more to say about human garbage?

I was just gonna say that that’s something that obviously really resonates with me.

It’s relatable, right?

It is!

My life doesn’t feel super stable to me. And that might just be an echo of past trauma, like the sense that lightning could strike at any time and the tower could collapse. That’s why that symbol is so meaningful to me, the tarot card of the tower, because I feel like that’s happened to me so many times. That I have a life that I feel is all set up, I put all the furniture in the dollhouse, and then something just comes along and bludgeons it into splinters.

I know that we’ve both been very poor at other points in our life. And I think it is profoundly, life-changingly traumatic.

It fucks you up, right?

Yes, it does.

I haven’t been that broke in a long time, and I still am astonished every time that I can buy groceries without checking my bank account balance first. Even if I’m spending like $30. I know that I don’t have to check it and I’m still like, “Should I check it?” No, I shouldn’t have to check it, I definitely have at least $30!

Right, these tiny little things that feel so weird and alien and difficult to parse.

That you carry those stupid fucking skills that you have to learn when you’re that poor. Not stupid, because you need them, but stupid because nobody should have to do that. I assume at some point I’ll begin to let go of that.

I imagine that it can fade with time. But seeing it in your work is so meaningful to me as someone who has been in so many disposable positions. I think it’s very beautiful that those are the people that you care about.

Those are my people. In Black Is the Color, where the guy gets thrown off the boat, I wrote that because I had just been laid off under pretty desperate circumstances. And around the time it came out I got laid off again.

I feel like this is an experience which is really, really emblematic of our generation as being totally at the mercy of people who don’t give the first shit about us.

Also, people who got theirs. And I still feel very bitter toward the people who laid me off. I think that was a terrible thing to do. I think it was terribly unethical. And I’m sure that they sleep great at night.

I’m sure that they do. That’s another thing, the fantasy at the center of so much popular fiction is that bad people feel bad.

Bad people never feel bad.

They don’t. We live in a world where people have the resources to end world hunger with a snap of the finger, and every day they don’t.

God, un-fucking-real.

I’m sure the tiny little tinpot versions of them feel just as good. They’re maybe not happy. I don’t know if they really have any recognizable human life anymore. But not guilty, that’s for sure. And your stories are very unsentimental about that. When people are guilty, it’s usually disgusting and manipulative.

Right. Well, I have no desire for that from the people who have hurt me. I don’t want an apology. As my friend, I’m sure you’re aware that I hate apologies. I hate being apologized to. Because it’s the same as when you have a toddler and they wipe a booger on their hands and then wipe it on you like, “I don’t want this, here you go.” That’s just another obligation for me, to process your apology. And I think this is not very nice, but even with Sean and Frank — who love me and would never do anything to hurt me purposely — they apologize to me and I’m like, “Don’t. Just do better next time. I don’t want to hear it.” Which is unkind, but it’s also how I really feel.

Yeah, I understand that. And I think there is something about the way our culture handles apology and guilt and punishment that is profoundly counter-productive. I’m not saying that your particular way of handling it is nice, you just said it wasn’t, but it has something that I don’t see in other people’s art and that I find a lot of value in.

Do you want to talk about sex now?

Yes! Yes, I always want to talk about sex, you know that.

Me too!

I’d say that’s a good 70% of what we talk about.

Well, yes, that’s true. And I’m definitely much more willing to just talk openly about sex with anybody. Like, engaging somebody in a conversation about sex can obviously be way of flirting with them. And I try to make it clear that I’m not necessarily doing that, I’m just curious about people. I’m curious about what they do in private. I’m curious about experiences that they’ve had that are different from mine. I want to know about everything that everybody has ever done. And sex is like a secret, it’s fascinating.

It is fascinating.

And it’s also a theater for us to work out a lot of the weird shit that goes on in our brains that we don’t normally have outlets for. That’s very interesting, in the same way that dreams are interesting. In that your weird subconscious shit just jumps out. It’s good to be aware of it, but a lot of people choose not to be.

That’s definitely true. The scene that came to mind when I was thinking about sex in this book is when the entity in the mirror walks Eleanor through stripping and spreading herself for him. And it’s this act of pushing against his restraints as an incorporeal entity. He’s making her body his without touching it. And she’s excited by it.

Yeah, and not just by making her show it to him, but by talking about her in a way that shows a sense of ownership. He describes watching her masturbating as a child, which presumably he could see because he is in a mirror in her room, I dunno. Or he’s just aware of it, because he’s part of the house. Or maybe he just made a lucky guess. But again, he is exerting the kind of masculine-coded dominance that we learn to expect from men. And that doesn’t necessarily work when it comes from an actual person.

Right. But since he is a voice and a presence —

He’s a fantasy creature. These are things that you — and when I say you, I guess I mean me — might fantasize about somebody saying to you. It’s like the fanfic that I wrote about being fat-shamed by Ralph Fiennes, which is like one run-on sentence with a Helmut Newton photo of Fiennes in a tuxedo that was taken in 1996, looking smarmy as he does. But it says, like, “You’re late for your date with Ralph Fiennes to go to a fancy party with a bunch of movie stars and he’s mad at you so he tells you your dress makes you look fat. And then you go to the party and Meryl Streep says she loves your dress and Ralph Fiennes pulls you aside and kisses your bare shoulder and tells you you look incredible or something.” And I had written this and posted it on Twitter. First I talked to you about it. I was like, “Do you think this is too fucked up?” And you were like, “No, it’s great.” And then I posted it and a surprisingly number of people, maybe two or three people, were like, “I too would be turned on by being fat-shamed by Ralph Fiennes.” And the thing about this is that a real man can’t do this. Even Ralph Fiennes from 1996 can’t pull that one off.

No, absolutely not.

It’s the kind of egg that you can have cooked exactly the way you like it but you cannot eat.

Yes, it’s quintessentially a fantasy.

There’s just no way that it could work in real life. Never ever. There is no nasty comment that a man has made about my body that I can actually be turned on by. And there’s no lack of those either. I have plenty to choose from. None of them turn me on.

The actual turn-on comes in taking the trauma and the pain of these things and sort of re-processing them through your fantasies.

Right! I created that story.

You’re in control of it.

Ralph Fiennes fat-shaming me doesn’t exist.

Pull off the Scooby-Doo mask and it’s another Julia.

Pull off the Scooby-Doo mask and it’s another Julia.

It’s just me. It’s just me fucking myself through a wall of facing mirrors into eternity.

I’ve heard you say that you consider your work to be pornographic.

I do, absolutely.

That’s something I love. I think that’s a ridiculous, arbitrary line that almost everyone draws consciously or unconsciously. What led you to think that way?

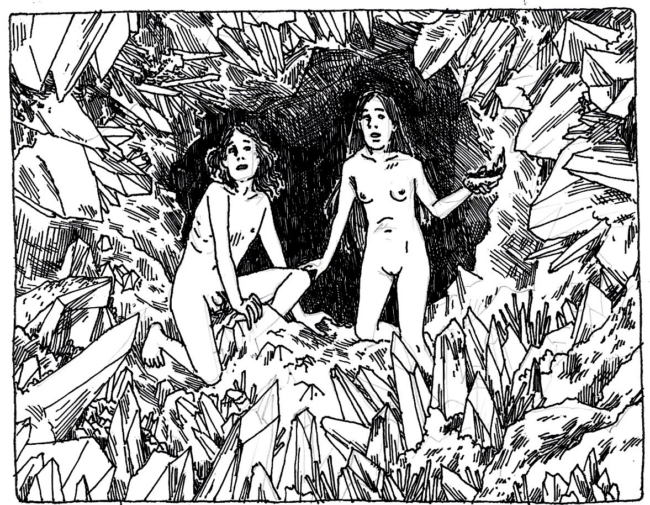

I write things that turn me on. I wouldn’t necessarily call my work pornography, except for maybe the Edgar Allan Poe comics that Sean and I did together. I think those are much more pornographic. But in my narrative work — those were just fanfiction — I would say usually the inciting image is something that is sexually interesting to me. I always describe it like you have a chair that you really like and then you have to buy a rug that matches and you have to pick out what goes on the walls — like you have to make a room for the chair to live in. But the reason for it is the chair. In the case of Vision, it was Eleanor masturbating in front of the mirror. I’m sorry, I forgot what the question was. [Laughter.]

That’s all right. I was asking you what led you to think of your own art as porn.

Because I’m writing about things that are erotic to me. And also, let’s say in the case of Dark Age, I wouldn’t necessarily masturbate to Dark Age — although there is a sex scene in it, which is mutual masturbation incidentally — but it is about experiences of mine with sexuality. I would distinguish between something that is pornographic and something that is pornography, because I definitely think my work is pornographic in that it is intended to cause sexual arousal. However, I don’t think somebody who is looking for something to masturbate to would necessarily seek out my work. I think they probably would not.

Because there’s a pornographic element —

But it also makes you feel bad about it. [Laughter.] It has all of this context that just ruins your boner, makes it run up and hide inside your body. Unfortunately. But pornography is a genre word, which I think there are great swathes of literary critics who consider genre to be anathema. Even Dylan Williams, who in many ways created my career — I wrote Flesh and Bone really for him. He had offered to publish something of mine, so I wrote a book that I thought that he would like. Not only thinking of him, but because he and I had a lot of interests in common, I wrote about those things. I had said, “Well, this is a horror book.” And he was like, “I don’t think we should necessarily say that in the press releases and stuff, because that’s pigeonholing you. It’s so much more than that.” And I’m not gonna say that he was wrong, because I think he knew what he was doing.

From a marketing standpoint, for sure.

And also, he was coming from a slightly different culture, from like a Gen X culture. I mean, I could take a guess at what the cultural reasons are for why elevate genre now, but people talk about “elevated horror” blah blah blah. It’s still just horror.

It’s just a way to make yourself feel more important for enjoying it.

It’s just a way to make yourself feel more important for enjoying it.

If you quote this, you’re gonna have to look up who said it, but the axiom I think of all the time is that literature is a luxury, but fiction is a necessity. [Trans. note: quote is from GK Chesterton.] You need genre stories to make sense of the world. You don’t necessarily need literature. If it’s too austere, good for you for enjoying it. But people need fairy tales, they need porn.

They need something to retreat into and they need something to look forward to, to grasp for.

And something to relate to.

Yeah. Not to be cynical about literature, much of which I love.

We’re a couple of literate bitches. [Laughter.] Fuckin’ English major.

Yeah, I know. But in the last 20 years, literature has become a succession of books that are titled, like, “The Aviarist’s Niece” and it’s about someone’s experience sorting her uncle’s collection of bird bones after he dies of malaria.

Yeah, “The Precognition of the Sloths.”

The purpose is to be rarefied.

The hifalutin noun of the hifalutin plural noun.

Yeah, those things feel so far away from the body. And I feel like your work proceeds from this place where horror is trying to inspire physical reaction. And that’s clearly what you’re doing with sex as well.

Well, here’s the thing: I feel like my philosophy regarding fiction is that it doesn’t do to try to be smarter than your audience. Because you’re not. Every single person who reads something that I write or that you write knows something we don’t know.

Absolutely.

And is gonna understand it in a way that we are completely unequipped to anticipate.

I got this really long email after I released Ego Homini Lupus about how I had written the mechanical action of a “quern” incorrectly. And a quern is a small grouping of two stones that you use to grind wheat or grain. It was a really boring email, but it was also really cool!

God bless that person. Where were they like six months before when you were writing the goddamn book?

I actually went back and edited it and uploaded a different version.

Good for you! I fucking love those people. God bless the person who knows all about the quern. I love a fucking weirdo who’s fixated on something that’s completely inconsequential to the rest of the world.

People who know esoteric, useless things but specifically from the realms of daily life, that’s so cool to me. I love that.

Obsolete chores? Fascinating.

The best. One of the appeals of historic fiction to me — and I flatter myself by saying that I see the same in your work — is the appeal of the obsolete chore.

No you don’t. This is definitely something we have in common.

We both love to make art about work.

I love old chores. First of all, I love work. As a Virgo, I like to work on things. There’s something very psychologically healing about doing a repetitious physical task. I was a printmaking major in college, so I did a little bit of printmaking. A little. It’s a BFA, so I didn’t do a lot. And then my day job for a long time, because I lived in Portland where this is a day job, was that I was always involved with letterpress printing. And one of the things that is so appealing to me about letterpress printing is that it is an entirely obsolete medium. It only exists to make weddings and bar mitzvah invitations for people who have far too much money. And even then, in many ways we — the letterpress printers of the world — are streamlining the medium in order to make it more convenient for people who want wedding invitations. But it’s so comforting that it’s almost addictive. Because you work with machines that have electrical components, but the machinery is very simple. And they’re built on a human scale. For example, a clamshell press, which is like an upright standing press that’s about the height of a person, and it opens and closes vertically. And you stick a piece of paper in, it closes and prints it, and then you grab it back out. You work it with a treadle, like an old sewing machine if you’ve ever used one of those. That’s the kind I learned to sew on, my mother had one like that.

Me too. My mother used to make some of my clothes.

Me too!

Go figure. For those of you who don’t know, Julia and I were actually born in the same building, a tiny birthing center in our little hometown.

We have a lot in common. And apparently our mothers made our ridiculous clothes.

Yes, very ridiculous. There’s a great picture of me in rainforest poison arrow frog patterned overalls.

I love it! My mother made me beautiful little prairie dresses. I wore them with these sweatery tights that we wore in the ‘80s. Anyway, the thing that’s so inexorably compelling to me about letterpress is that these machines are designed to work with a human person. The human figure is an essential component in the machine, it can’t work without a person who has a foot to run the treadle, a hand to touch the flywheel, another hand to put the paper in and take it out. And because you control the speed with the treadle, it works at the pace that your body chooses, but then the flywheel creates a momentum so then it replicates that rhythm on its own. but it’s a rhythm that originates in your body. And it’s a different experience that I had as a letterpress printer in 2010 or whatever from what a letterpress printed in 1910 would’ve had. but in some ways it’s the same. There’s also the action of typesetting, which I was lucky to work at presses that involved typesetting because most letterpresses now do polymer etched plates, which is basically the same as a rubber stamp. Because people want custom lettering that you can’t do with movable type. But I did work at some places where I actually did a lot of typesetting. I’m sure you’ve seen a California job case that has different sections where the different letters of the alphabet go, and they’re arranged that you have to sit in a certain way and the letters that you use most often — like the Es and the Ms — are closer to the center where your hand is and they also have bigger holes because you have to have more of them. And then on the periphery there’s like the Ls and the Qs, and if you do this often enough, which I was doing full time, you acquire a kind of muscle memory and you don’t have to look to do it. You just grab the letter and you stick it in the composing stick. And there’s something wonderful about your body doing a thing that you don’t have to think about very much. The information goes straight from I’m reading the copy that I have to typeset, my hand is picking up the letters, and I’m not thinking about it at all. I’m just an instrument. Not entirely unlike making coffee drinks as a barista, which I also did for a long time. But you just have a sense of what your body should be doing and it works independently of whether or not you are thinking about it.

Yeah, I remember from when I worked at a kitchen or a car wash. Repetitive motion, small specific tasks you have to learn.

It feels good! If your inner monologue is oppressive to you, that kind of work is a blessing.

It really is. It can help.

So, when people respond to my work by looking at it as people are oppressed by drudgery, they have all these pointless chores, I think—

That sucks!

It does suck. And I think that it’s partly born of a life experience that doesn’t involve a lot of chores maybe?

I also think it’s this idea of fiction we have as adventurism and self-expression.

Oh, like if someone isn’t doing something dramatic, then it must be sad.

Right. If someone is just living their life, then that’s automatically miserable. And certainly you write about a lot of people who are, incidentally, miserable while doing the things that constitute daily life all over the world throughout time.

Right. If someone is just living their life, then that’s automatically miserable. And certainly you write about a lot of people who are, incidentally, miserable while doing the things that constitute daily life all over the world throughout time.

Oh, yeah. Definitely.

But I don’t think that they’re miserable because they’re making bread or spinning or what have you.

Those are like the best things!

Right! Those are things that make you feel useful, that have a concrete impact on the world.

I’ve always meant to write a book where a person is typesetting, but I haven’t done it yet. Oof, the experience of if you’re typesetting something and then you drop it, or dropping an entire type case. You cannot even imagine the horror. It takes hours and hours. But also how interesting. Like, how great would that be to put into a comic? I would love to.

All these things, to my eye, take the place of what would normally be occupied by violence and action.

Yeah, or just the protagonist ruminating about stuff while he walks around. Those little narrative boxes.

This is much more interesting to me, because it gives this impression of people who are a part of the world around them. They’re not just floating around having thoughts about what they mean.

Yeah, they’re participating in the world. They’re participating in the things that make the world happen. You need to have milk, you need to have wool, you need to have bread. And I’ve done all those things, like baking bread, spinning yarn or thread, and I don’t experience those as drudgery. Like, sometimes it’s a choice, I guess, but there’s also a joy in the sensation of your body having mastered this essential skill. OK, you know — I know that you know — the book the Ox-Cart Man by Donald Hall?

Yes.

So, this is a really important text to me, because it’s all about work. And again, there’s no value judgement of “Is this a waste of time to do this work?” Because that’s the implication when you say that this is drudgery. That nobody should have to do these chores. The ox-cart man, his family does all this different stuff. They make maple sugar, they collect down from the geese, they make yarn and then they knit mittens and make brooms, and they make a harness for the ox and they raise the ox. They have so many skills and make all kinds of different things and there’s a sense that the work is fulfilling in and of itself. That having made something useful well is meaningful in and of itself. And that might be a particularly New Hampshirey feeling to have in the world. I think we’ve talked about before.

We both have more than a little bit of the puritan work ethic idea.

I’m such a New Hampshire woman no matter where I go. I cannot stand to live there, but it lives in me.

Absolutely. You grow up in this place where certitude and work are so highly valued and it gets into your bones.

And just the sense that ... OK, everywhere you go in New Hampshire and other places in New England, Vermont particularly, you see these low stone walls. They’re not more than a foot or two high. And they’re mostly granite. And they are property borders made by farmers finding rocks on their land and bringing them to the edge of their land and piling them up. They’re ubiquitous and, first of all, those are so natural to me to see that it was shocking to me to realize that they didn’t exist in other parts of the country.

Right, almost nowhere else.

I was just like, “This is what people do around the edge of their property.” But it’s also an exemplar of a thing that’s eminently practical to the point that it almost doesn’t bear thinking about. Like if you find a stone that’s in the way when you’re tilling your land, you take it to the edge of your property where the border is. There’s a sense of being part of the things that you work with. And the products of them are not — not that they’re not separate from you, but that it is reasonable for people to use the things in their environment to create signifiers that are meaningful to other people in the same environment. Does that make sense?

Yeah, it does.

It might just make sense because it’s a tautology. [Laughter.]

But also, it’s describing a way of being in the world. And it might be one that is in some ways specific to New Hampshire, but in other ways it really describes especially the way that women live.

True. I mean, I can’t say whether or not it’s specific to New Hampshire or to women.

I’m sure that piling stones is a rich global tradition in many other places.

Cairns exist worldwide, right? I’m gonna tell you what your interview needs. The thing is that when you and I talk, we say so many things that the rest of the world is dying for the lack of. You have so much wisdom to impart. Also, so much mean shit to say that we haven’t said. That might be a bad call. But what would we be saying if we weren’t recording this? Aside from me reading you the corpse-fucking part of The English Patient?

That was very good. That made me feel so wistful.

Makes you want to cry and fuck at the same time, right?

Exactly! It definitely made me both horny and miserable.

My favorite feeling. Crysturbation.

I think at this point, if no one were listening, we would start talking about how trivial almost all art that touches on these subjects is in popular culture, in comics and otherwise.

This is important, because I think that most people who have the privilege of making art for a living don’t have that much experience with eating shit. I mean, we’re very lucky. I’m so aware that it’s a series of experiences of falling down the right set of stairs.

Right. There’s hard work involved, but ultimately we were at the right place at the right time enough times that now we get to do this for work. But we have eaten our fair share of shit.

And there’s a lot of art that is not about eating shit, because that’s not the experience of most people who are making art for a living. Which is why we need to create a society where poor people can make art.

Shit eaters of the world unite!

Unite and take over.

This brings me to my last point. We’ve talked so much about fantasy and about work and labor and daily life, and I feel like Vision is really beautifully ambivalent about these things. Fantasy is so vital to Eleanor’s life, but when she reaches for it and tries to make it real, it rips everything apart. Not because it’s terrible in and of itself, but because it’s insubstantial. There’s nothing there for her. You have this incredible image of her plunging into darkness like Alice in Wonderland falling down the rabbit hole, but there’s nothing to fall into.

But still, even knowing that, in many ways her relationship with the ghost in the mirror is preferable to the other relationships in her life. The doctor that she’s close to is really only interested in her as a body. He’s not engaged with her emotional issues. She tries to talk to him about her brother and he’s like [Shrug sounds]. And he’s partially culpable for that.

Yup, he’s providing the medicine that —

— that knocks Cora out. Even though — to refer back to a metaphor I alluded to earlier — even though you cannot eat the eggs, they’re cooked so perfectly that they’re still preferable to the ones that you could eat. The ones that you could eat are practically inedible.

I think it’s very special that you show all these realizations so plainly and then allow the reader to sit with the impossibility of resolving any of it. You’ll always be chasing something you can’t have.

Yeah, those are unresolvable issues. I was tweeting about this today. What do you do with desires that you cannot earn the fulfillment of? Are you obliged to give up on them? Or do you just keep on wanting them, fruitlessly?

Do you dash yourself to pieces against them?

What do you do when you want to be fat-shamed by Ralph Fiennes in 1996 shot by Helmut Newton?

That time is gone, that Ralph Fiennes is gone. And even if you could have him he would do it wrong and hurt you.

Even if you could have him, he’s not that guy.

No. No one’s that guy. That moment doesn’t exist. But it’s essential.

Because in some ways, fantasizing about that guy is better than a real guy.

Yeah, it is. That’s a very quick and concise way of putting something that I really appreciate about your work: It understands that fantasy is preferable in a really prosaic way. Sometimes it’s better to just jerk off to the idea of what you want than to go out and find someone who will disappoint you by doing it wrong.

I mean, that’s just realistic. People all the time choose to masturbate rather than have sex that they could have that might fall short of what they want. This is gonna be opening a whole other line of conversation, but the question of infidelity, like why do people cheat, is really simple to answer for me, a person who has cheated in many relationships. Which is that blowing up your whole established relationship is a real pain in the ass. And having something that’s pretend and temporary doesn’t necessarily seem to infringe on that. It’s like a separate thing.

It’s a daydream.

Of course it’s not experienced in that way to other people involved.

Well, now that we’ve established you can never touch the objects of your desire or know relief from life’s essential inadequacy, maybe we should hop forward to the end.

Oh yes, let’s.