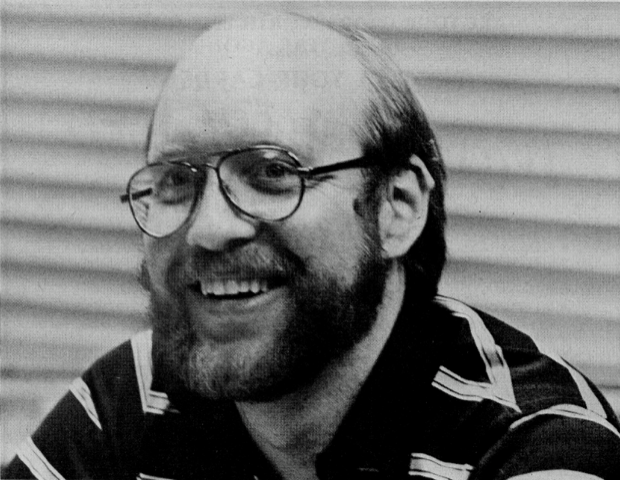

In terms of his legendary career in comics, Steve Englehart was a catalyst of change, even as his stories demonstrated reverence and creative inventiveness regarding established continuity. I've had the pleasure of interviewing Englehart twice before and wanted to catch up with him to discuss his career and influences, artists he's worked with (we discuss both Sal Buscema and Herb Trimpe herein), the comics industry, and the many strong female characters he wrote over the years. This interview was undertaken throughout 2018 and 2019, several questions at a time, via email. - Jeffery Klaehn.

Jeffery Klaehn: What initially led you to become a comic book fan?

Steve Englehart: The art. When I was a kid in the 50s, the stories were serviceable but little more. On the other hand, Dick Sprang!

What about Sprang’s art appealed to you?

Bizarre exaggeration, unlike anything else in comics.

How central was New York to comics in the 70s?

You had to physically go there to work in comics. It was before FedEx or the internet so physically handing things to people in their offices was the way it had to be done.

What was it like to be working in comics at that time?

It was the best. We were ushering in a new age, which we kind of knew - taking what was great and making it even better, month by month.

What do you mean, a new age?

The next generation in comics.

I’d like to ask you about some of the individuals who influenced your career in comics and would appreciate it if you’d share your memories and reflections, starting with Neal Adams.

Neal was a seriously good guy who talked the talk and walked the walk. You could absolutely count on him to do the right thing. He decided to take me on as his art assistant, the first time he’d done something like that. I was in the Army at the time and he had to talk me into it – I wanted to do it but didn’t see how. Thereafter, I met him every Friday night at the DC offices and worked till after midnight. Every Saturday I’d go to his house and work all day. Every Sunday I’d go back to the Army. When I realized I was a conscientious objector, Neal decided to go down to my Army base in Maryland on his own dime and testify to my sincerity. Just a great guy.

What year was that?

1970.

Julie Schwartz.

I first met Julie when, as a fan in college, I went to the DC offices. I was offered – and accepted – the chance to sit and talk with Julie, who gave me a half hour of his time - and then, when that time was up, gave me some original pages from a Brave and Bold with the first JLA stories. Julie was always involved in the comics scene so I saw him on and off continuously whenever I was in New York, which was continuous after I moved there – and then I worked with him on the first Batman run. He was well known as a hands-on editor who ran his books himself, but he let me do my thing the way I wanted, with only the gentlest of editorial hands. In other words, he knew how to get the best out of his people, however that might work. Truly worthy of all his honors.

Stan Lee.

Also worthy of all his honors. A unique talent and interesting company. I overlapped him in the Marvel offices for only six months but he was a guiding spirit my entire comics life.

Roy Thomas.

The most salient fact about Roy is, he was drilled by Stan to sound exactly like Stan – but as he went forward, he began to stretch that mandate – and when he became Editor-in-Chief himself, he let us new writers be completely ourselves. That single decision allowed the great leap forward we took in the 70s, so there’s no overstating how crucial that was. But that middle part, where he was stretching Marvel’s boundaries himself, made him my favorite writer before I started writing myself – and of course, he decided that I could write in the first place. What was interesting to me, after he gave me Avengers, was that he liked to start with a plot and add character, while I started with character and added plot. Nevertheless, we both understood what made fun comics and tried to end up there every time.

Following from this, how did you plot your “Secret Empire” storyline in Captain America, and what was your intent with this particular story arc?

I was writing Captain America and America’s president was a crook. I could not see how Cap could ignore that. Since I’d created the idea that he stood for American ideals, he had to react to this threat to those ideals. So I looked at the overall shape of Watergate and created an analog of it. When I wrapped up my story, Nixon had not yet quit, but there was no question of his guilt, so then I had to see what Cap would do when the ideals were shattered. The intent was to explore Cap’s character, which is pretty much always my intent in my stories.

Do you think you’d have that degree of creative freedom at Marvel today? Could you see your “Secret Empire” storyline happening today?

No.

Jenette Kahn.

Jenette hired me to save DC after all of their stars had left for Marvel. Getting me to come the other way was her first talent decision. She was good as a businesswoman, both in dealing with the suits upstairs and the talent downstairs, but like everyone at DC, the upstairs came first. I got along with her pretty well because I understood that, in the moment, but later, when DC started pretending I hadn’t saved DC, I was less enthusiastic. It was she who suckered me into saving the Batman film based on my run for a deal that violated Writers Guild rules, knowing I didn’t know Writers Guild rules.

Can you please elaborate on this?

I was told they couldn’t make the film without me, but they didn’t offer me a film contract. I have no idea who knew what at the beginning, but by the time I’d gotten them to understand how the Batman worked, somebody figured out that I was working outside Guild rules and they started trying to erase me from Batman’s world. Unfortunately for them, the comics have remained hugely popular; but Marshall [Rogers], Terry [Austin], and I were not asked to do any more of them for the next thirty years.

You mentioned editorial interference in another interview you did a few years ago.

DC has always been very corporate, and that included having a “look” to the art they published. Marshall and Terry did not look “DC” so they were, according to Marshall and Terry, screamed at about it, and told to change. But to their obvious credit, they did it the way they saw the Batman anyway. And fortunately, DC was so moribund then that DC had to put up with it.

What about your relationships with Len Wein and Jim Starlin?

Good relationships. Len and Marv Wolfman and Gerry Conway were already working in New York when I got there, and they welcomed me into the fold. While Jim and Alan Weiss arrived about when I did and we fell in together.

You also hired a young twenty-two year old Canadian artist named Todd McFarlane in 1983, which resulted in his having a back-up story published in Coyote the following year.

I think I gave Todd his first job in comics, and I helped him get his green card. He used to call me "Mr. Englehart."

Have you ever considered creating new creator-owned properties and publishing via Image, or another publisher?

I’m writing an extremely long and complex series right now, challenging myself as a writer, and when I feel I’ve got it right, then I’ll look for an artist and publisher.

Can you reveal any further details about this? Will it be a creator-owned property?

Sure, but that’s all I’m prepared to say until I’m done with it, because it surprises me every day as I work through it.

Are you aware of comics writer Tom King’s recent suggestion that you be given creator status on Batman? What are your thoughts on this?

It’s very nice of Tom, but anyone who’s seen Batman and Bill, about Bill Finger’s family’s troubles with DC, will not be holding their breath.

How do you write scripts that effectively tell stories comprised of text and sequential art? In terms of craft, what’s involved? How do you approach visual storytelling, as a writer, and what influenced your approach? You were only twenty-four years old when your first comics work was published. Did your approach change over time, depending on the artists you were working with on particular projects, as you yourself continued to learn and develop as a writer?

I just have a feel for it, I guess I can say after [all] this time. I’ve worked with people who don’t – can draw pretty pictures but can’t tell a story, or write words that don’t tell a story. However it happened, I can tell stories. And it’s so instinctive to me, I don’t ever think of it in terms of craft, so I have nothing to give you there. I’ve certainly learned from others before and around me, but everything goes into what Jimmy Carter called “the Cuisinart of my mind” and joins the vast sea of things I know and can draw upon.

Did you ever meet or have any interaction with Jack Kirby?

I met him a few times, always in a professional setting. We never hung out together.

What about Steve Ditko?

I met him once. He was reserved by nature but was talkative if he liked you. I enjoyed that meeting a lot. And then later I wrote The Djinn especially for him, trying to hit all the “Ditko” buttons for him, minus the polemics.

What can you tell me about "Night of the Stalker!" – your Batman story in Detective Comics no. 439 (Feb–March 1974)?

My roommate at the time, a really nice artist named Sal Amendola, had this story that he, his brother, and Neal had worked out, but they needed a writer. The idea was that Batman would never speak, so of course I threw in a few words, which editor Archie Goodwin removed, to everyone’s benefit. It’s a real one-off kind of thing, unique and fun. It’s too bad that Sal didn’t pursue comics after that.

What did you think of Bob Haney’s Brave and the Bold Batman stories, with Jim Aparo?

Bob Haney was one of DC’s better writers, and his stories in B&B and elsewhere were always very solid.

Please tell me about Amazing Adventures, featuring the Beast. Your tenure began in 1972 and featured brilliant covers by the likes of Gil Kane, Jim Starlin and John Romita. And with your stories, you shaped all subsequent interpretations of the character.

The Beast was my first superhero comic. I’d worked my way up to that and Roy was willing to use me on the big stuff. Now, The Beast, as a member of the failed team called the X-Men, was the smallest of the big stuff, but he was a superhero, whom I had liked in that X-Men book, and I wanted to do the best possible job I could, for whatever my career might turn out to be, but mostly for him. I became a Marvel guy because I liked the characters and I wanted this one to be okay. My big change was deciding that the “intellectual” guy who’d been a nerd previously was probably a stoner in the early 1970s. So I wrote him as smart but loose, funny. Once again, I wasn’t trying to shape all subsequent versions of him. I just wanted him to be what I thought would be a good character in the moment.

Did you color issue no. 12 yourself?

Yes. When I was working with Neal, he taught me to color so I’d have something to tide me over if art jobs got scarce, and I liked it a lot so I continued to do it whenever I could, even after I started writing.

You first collaborated with artist Sal Buscema on The Defenders. You went on to work with Sal on Captain America as well. What can you tell me about his art, his visual storytelling, your collaboration?

I wouldn’t be the writer I am today without Sal. Roy gave me complete creative freedom, but if I’d gone flying off down some yellow brick road and the guy I was working with so much had said “I can’t draw that” or “I can’t understand that,” I’d have had to modify my approach. But that never happened with Sal. He could draw anything, and he could tell the stories with such seeming ease, that I could take things as far as my brain would let me. Following on what I said before, the main aspect of comic art is storytelling. Good art is important but storytelling is even better.

What influenced your approach to Captain America?

I had my first “big” superhero, he was failing to find an audience, everybody else had tried and failed to solve that problem – so if I was not to fail as well, it was up to me to solve it. I took my best shot, decided Cap stood for American ideals rather than American wars, and it worked, because American ideals resonate with everyone who believes in America. I’m really happy, not just for me but for America, that that’s been his characterization ever since. It’s good to have something to showcase the ideals.

Had you read Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s original Captain America (nos. 1–10, 1941–42) issues, published with Timely?

Yes, and I wasn’t impressed. I’d seen the best stories reprinted here and there, so I expected the whole run to be at that level and it wasn’t. I honestly believe that if Stan and Jack hadn’t brought him back in the midst of the Marvel boom, he’d be like The Ray or those other mostly-forgotten 40s characters.

What about Kirby and Lee’s Tales of Suspense Captain America stories in the mid-1960s?

Started out great, but a series set in the 40s didn’t excite kids in the 60s all that much - and when they shifted to current time, they quickly ran out of ideas. They couldn’t figure out how to take That Guy and do him in the contemporary world.

What did you think about Steranko’s Captain America (nos. 110–111, 113, 1969) issues?

Steranko was always great. I loved everything he ever did.

Please tell me about Mantis and the Celestial Madonna story. What was your inspiration, your intent?

I wanted someone to shake up the Avengers, so I came up with a femme fatale, but right after I did, I also came up with the Avengers-Defenders Clash, and I needed to use my femme as a solid team player, not a disrupter. I found that interesting – a character I’d created for a purpose who now had no purpose, and as a young writer exploring my parameters, I started letting her tell her own story – meaning, every issue I’d tell my overall Avengers story, with my various character developments, and things then would happen that she had to react to. Those reactions – or what I conceived her reactions to be – revealed her character for me, step-by-step, as the worlds I was definitely creating grew bigger and bigger, and in that way the femme fatale became the Celestial Madonna.

In writing titles like The Avengers, The Defenders, Captain America and The Hulk, to name only a few of the Marvel titles you wrote during the Silver Age, were you a fan of the characters before you landed the various writing jobs on these titles?

Absolutely. I read all the comics out there, from all the companies, and was a fan of pretty much all of them - so I liked the Marvel guys, but also the DC guys (in their way), and the Charlton guys, and the Gold Key guys, and – I liked comics.

What Charlton and Golden Key books did you most like?

All the Charlton books once Dick Giordano became editor – Captain Atom, Blue Beetle, etc. – and Magnus Robot Fighter and the Barks Duck books from Gold Key. I read everything but wasn’t much interested in their Tarzan and such.

Do you feel there was more diversity then, in terms of genres?

Sure. I liked the western, romance, and monster books. But like most people, I liked superheroes the best.

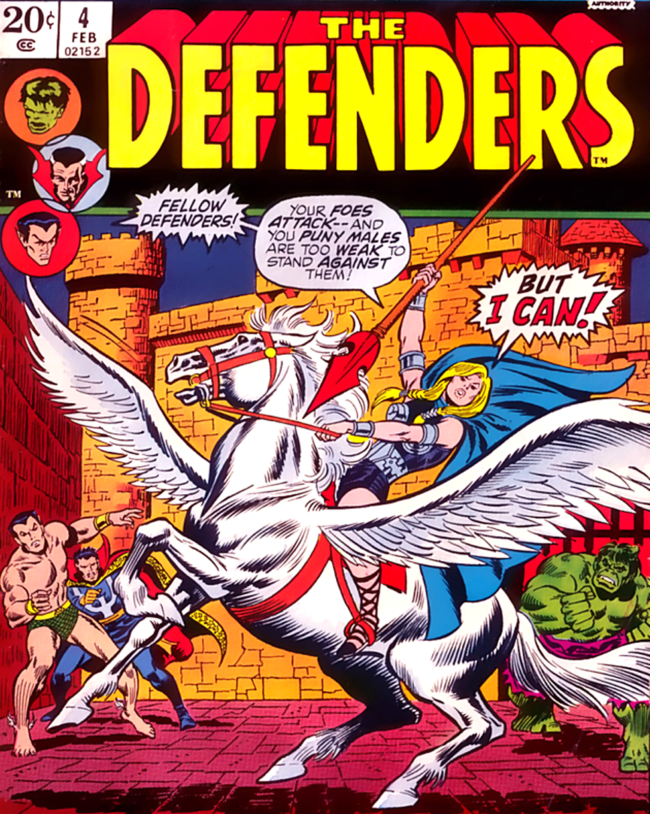

Was writing The Defenders a fun assignment for you? What motivated you to add the Silver Surfer and Valkyrie to the team?

Sure, it was all fun, and I particularly liked those characters. But since the team did not function as a team, I could easily bring in other loners. The Surfer had touched base with them previously, but it continued an all-male team and I wanted to expand on that, so Valkyrie.

When was the greatest era for comics, in terms of creativity and possibilities, in your view?

The 1970s.

Why?

Our books had to see and meet their deadlines. Anything else was entirely up to the individual creator, so a lot of interesting avenues were explored without regard to any censorship.

Please tell me about your first impressions of Frank Brunner and about the creative synergy between the two of you, working on Doctor Strange.

I knew Frank from knocking around New York, but I didn’t know him well until he asked for me to be the writer on Dr. Strange. Since he had ideas about the series which meshed with mine, we did all the books together. Every time an issue was due, we’d meet up for dinner, at his place or mine, and afterward sit down and hammer out the issue, until we had something we both liked. Since it was my job to make the story make sense, I was more rigorous about that end of things, but it all came from the flow between us.

Which of your stories on The Incredible Hulk (nos. 159–172, 1973–1974) are your personal favorites, and what was it like working with artist Herb Trimpe?

My favorite was the Harpy run at the end of my tenure. Herb was a pleasure to work with. He was always on an even keel; nothing fazed him when doing the comics.

I'm a huge fan of his art. I still can't quite fathom that he was fired from Marvel in 1996 after working there as an artist since 1967, after co-creating so many characters, and after penciling so many books for Marvel – including the first published appearances of Wolverine in The Incredible Hulk nos. 180 and 181, 1974.

Me, either. That did faze him, and me.

The two of you co-created Wendigo – what made this character a perfect opponent for the Hulk, in your view?

Well, it was a human who’d been turned into a monster, and it was the humanity of that strip that sold it. The Hulk wouldn’t provide much along those lines so that’s why the strip had a good supporting cast – and the best villains had some human story, as well.

You also co-created The Shroud in Super-Villain Team-Up no. 5 (April 1976). What was the inspiration behind this character?

As a Marvel writer, I thought I’d never get to write the Batman, so I took some Bat-traits and mixed them with some Shadow-traits so as not to get sued and made my own homage to those dark night characters. Then, of course, things changed…

Did you read Uncanny X-Men no. 140 (Dec 1980) when it was published? Have you followed characters you've created and/or co-created after you've left various titles, as these characters have been utilized by new writers, artists? I think too of Kevin Smith's Batman: The Widening Gyre (Aug 2009-July 2010), which revisited Batman's relationship with Silver St. Cloud, made famous by your Detective Comics run with Marshall and Terry.

No, I was out of comics in 1980 so I read that X-run later. But in or out of comics, I usually did not read series after I’d written them, and this is a common trait for writers. You do your best to figure out who the characters are, so then other people’s figuring doesn’t work for you. But, for example, when Doug Moench and Paul Gulacy changed Shang-Chi so radically, I was happy to follow along because that was not covering the same ground, character-wise.

How did Shang-Chi, Master of Kung Fu, come about?

Starlin and I stumbled upon the Kung Fu TV show and wanted to explore that realm ourselves. How nice that we had that option.

What factors led to you leaving this title?

Starlin and I wanted to do a bi-monthly book. We had to work at it to convince Marvel to do it because they thought no one else was interested, but almost as soon as we debuted, the Kung Fu craze exploded. All of a sudden, Marvel wanted a black-and-white magazine to go along with the color series – a red flag for me because I like to have only one reality for my characters – and then they created Iron Fist, and then they wanted Shang-Chi annuals, and it all got to be too much for us to do what we wanted to do.

The comics industry was very male-dominated in the 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s. Did you see any major changes here throughout these decades?

Not really. There was Marie Severin, Glynis Wein, Ramona Fradon across town, and a few others, mostly letterers and colorists. I didn’t see much change in those years.

I want to ask if you could please share your thoughts on some of the strong female characters you've written. What was your intent with Valkyrie? What was your vision for her character?

She had to be very strong to hang with the Defenders, but I liked the idea that it was all overlaid on a psychotic. Since that was more complex than any of the other Defenders’ personalities, I thought it would make for interesting storylines (for example, the Hulk does not do complex). I had to give up DEFENDERS once I had AVENGERS, because two team books would have been tough, but I was always sorry I didn’t get to do more with her, because there was a lot to do, as others after me showed.

Patsy Walker aka Hellcat, whom you had join the Avengers –

She wasn’t driven by fate to be a super heroine – she just wanted to be one and enjoyed (almost) every minute of it, without all the angst.

The Scarlet Witch –

When I took over Avengers, I was told that Wanda was supposed to do one hex and then be too tired to keep going. I thought to myself, “She’s a damn Avenger, isn’t she?” and deliberately set out to make her stronger. It could be that that decision drove all my strong women afterward. She got to be very strong, and at the same time, she was always very loving toward the Vision. She and he were the linchpins of a lot of my Avengers, the ones we followed while everyone else had more short-lived arcs, and they got married and then had kids - the greatest Marvel couple.

And Silver St. Cloud – if this was a "behind the scenes" commentary on your "Batman: Strange Apparitions" arc, as your run on Detective Comics with Marshall Rogers and Terry Austin was retroactively named by DC, what influenced your characterization of Silver?

On that series, I wanted to make the Batman a grown-up, to appeal to grown-ups as well as typical (younger) comics readers. Specifically, I decided to give the Batman a sex life, which was unheard of in comics to that point. But a real sex life involved more than one-night stands with the vapid girlfriends Bruce had had before, so I needed a woman who was as accomplished (at least in the business world) as Bruce Wayne, and strong enough to bond with his intense personality. So...