As a teenager in the early '90s, it was an event when I came across a copy of the collected Watchmen at my local library (it was filed under humor, alongside Bloom County and Maus). But these days, comics are everywhere, especially libraries, with middle grade graphic novels not only driving comics sales, but the entire publishing industry. Much of this can be traced back to the runaway success of Bone, and its creator, Jeff Smith.

I sat down with Smith over Zoom to chat about the middle grade revolution he kicked off, the power of librarians, the many incarnations of his dawn-of-man saga Tuki, and Netflix’s unceremonious cancelation of an animated Bone.

-Jason Bergman

* * *

JASON BERGMAN: Your last major interview with the Journal was almost 28 years ago, so there's a bit of catch-up to do here, but I’d like to start with Tuki, your current project. What was the genesis of Tuki? What sparked the idea?

JEFF SMITH: I've always been interested in human evolution. When I was 14, the famous Lucy was discovered, the [3 million-year-old] fossilized remains of a small female that shared features and attributes in common with both humans and primates. That was a big, big deal. What was this, 1974, I think. There were stories in Life magazine. There were specials on TV, National Geographic. Like I said, it was a big deal and I was hooked. The whole idea, it was just astonishing that they discovered the missing link basically. That was probably what I really got into. I shared this interest with my dad. We would always go to museums and we were fascinated by that kind of stuff.

Right near there is the Olduvai Gorge. That's the famous archeological site that the Leakeys worked on and where they discovered many famous fossils and proved, basically, that over time, millions of years, our human ancestors all had very deep roots right there in East Africa. And going there blew my mind. I really felt something special about this place, about this concept. I've talked about this in the Tuki books, but I'll repeat it for you. I actually had a little vision while I was standing right on the spot. There was a little marker there where they found Paranthropus boisei's skull, which was like three million years old or something, I can't remember, maybe two million.

I remember standing there and looking up and there's the wall of [the] ravine. Up above there, you could see some palm trees swaying. I remember having this picture in my mind of all these species, multiple human species, Australopithecus, Homo habilis, all these different ones, Homo erectus, all walking around together, almost [as if] they're in a market, interacting with each other. I was really taken with that concept, that idea, and it stayed with me. The rest of the trip, even though I had no idea how I would ever do a comic about Africa, I took lots of pictures of trees and rocks and land because I was like, someday I might want to do a story about this.

You said that was '95. You were still years away from finishing Bone at that point.

That's true.

Had you toyed with other concepts before settling on what became Tuki?

I toyed with other concepts. I think at one point my original plan after Bone was to do a version of Robin Hood. Another thing I've been fascinated with my whole life, and done deep dives into. All the original songs, what is possibly real and what's not real with the Robin Hood legend. And that's what I was thinking I was going to do, but it was another 10 years almost before I finished Bone. Before then, I got interested in noir, and science fiction, and multiverses and parallel universes and stuff like that. And that's the direction it went [with RASL]. So Robin Hood went by the wayside.

Did the Africa vision seep into anything else you were toying with, or was Tuki the one?

It seeped into Bone! There's an important moment in Bone where Thorn, who's the mystical center of the story, she's awakened to the possibilities of the world and the Dreaming, which is sort of this unseen world in Bone. And she's visited by these creatures that look almost like stick figures with almost like a baboon ring of hair, or almost like a-- well, anyway, I'm getting into too much detail. It was just silhouettes coming through the jungle and there was this whooshing sound in the comic. Well, I dreamed that, my second or third night in Kenya, and I was really struck by it. I didn't know what it meant. It doesn't necessarily mean anything, but it was a really strong image, so I put that in there. I'm not 100% sure what it represented, but I made it all fit and work into Bone.

Do dreams frequently influence your work in that way?

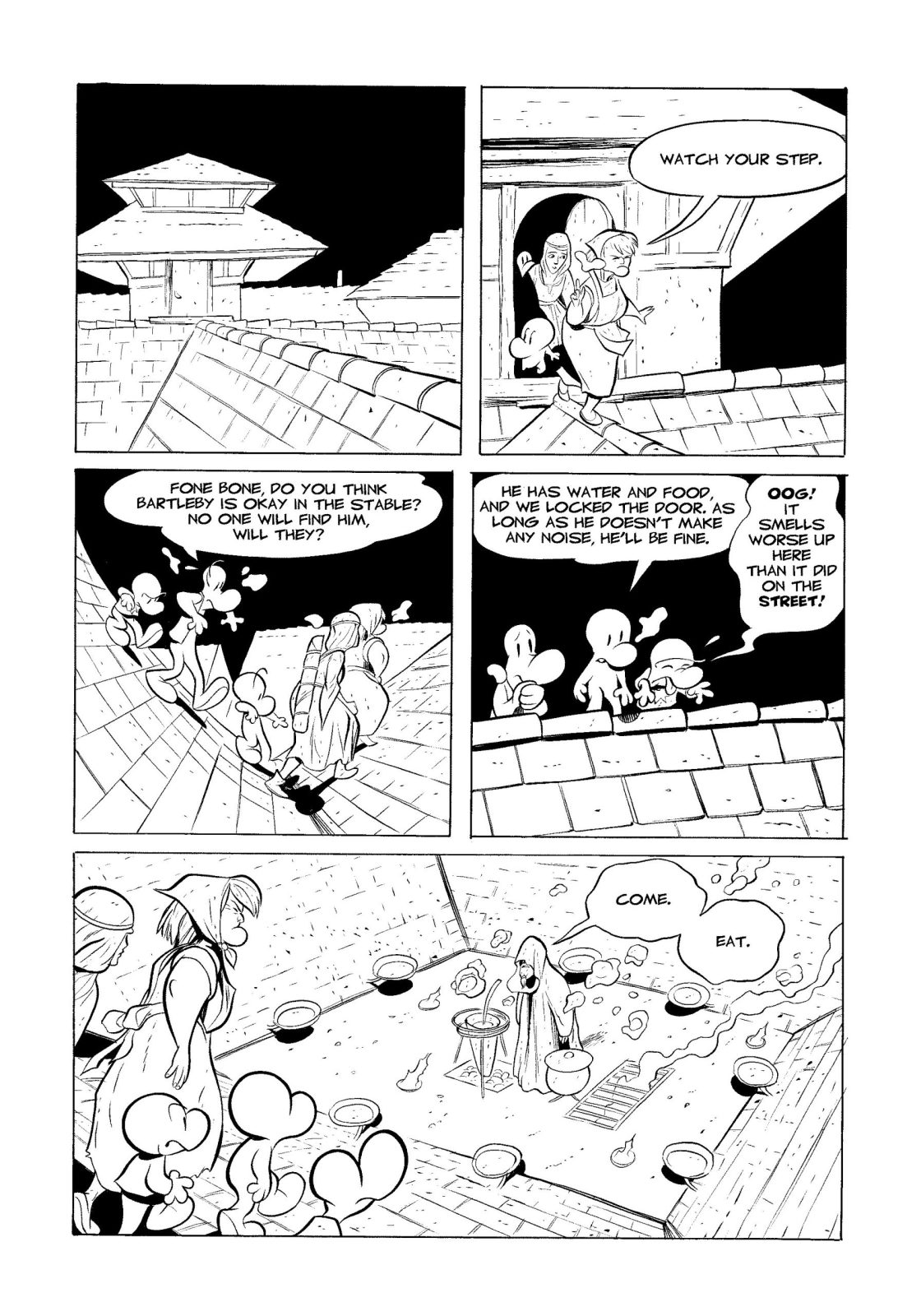

Yes, sometimes. Not a lot, but another dream that appeared in Bone towards the end of the story, they go to the city of Atheia, which was the kingdom prior to the fall 15 years earlier. The kingdom is still there, and Gran'ma Ben and Thorn and the Bones all meet in secret with a little group of loyalists to the old royal family. They meet in a rooftop kitchen, where four roofs converge down into a square and coming out of the roofs near the floor are these little-- they look almost like frying pans and someone comes and serves food into each one. That was an exact dream I had, no idea where it came from or what it meant. The whole rooftop kitchen and going over rooftops to get into it is exactly from a dream.

Do you use reference for all of the vegetation and animals throughout Tuki?

Yeah, pretty much. I did that a lot with Bone as well. In the early issues, there's some more generic, oh, that's a tree and those are leaves. But even then the trunks were very similar to what we have here in Central and Southern Ohio, but I always would [use reference] for accuracy because the Bones are so not real. I needed really real stuff to keep the story grounded in some way. So yes, in Tuki, not only did I have my own photos to use as reference, but we have the internet now and I can just look up, like, what does a dense forest in East Africa look like? I can extrapolate from these photos.

But at the end of the day, Tuki is–and Bone was as well–still fantasy. Is that sense of being grounded important to you, for the story you’re trying to tell? Where is the line?

Where's the line? Well, it's fantasy in that obviously, I can't know what happened two million years ago. And I've made up a little situation where our most direct ancestor Homo erectus was the first in this long line to actually control fire. I speculated, well, what were the other human species that were [around at that time] doing? The Lucy species, the Australopithecines, were all still around. Homo habilis was still around - the first to make stone sharp choppers. Why didn't they pick up the fire and start digging it? I thought, oh, well maybe it was like a taboo. Maybe I'm going to say the older species were hardliners. That it's taboo to do fire. So that's all fantasy, that's all just completely made up.

Also, I'm a fan of older epics, everything from Le Morte d'Arthur to the Iliad and the Odyssey. I've always talked about how those books changed me and changed the way I write, the way I think. And they all have fantasy in them. The Illiad and the Odyssey, in both, the gods are just fucking with humans the whole time, but the humans are supposed to be real humans. They're told as if they're about actual people that lived, real heroes. Same with Le Morte d'Arthur and the way that the story is presented, he was the real first king in a real place called Britain. And yet you've got Merlin and you've got fanciful holy grails and fountains surrounded by maidens that can send you off on a crazy adventure. I just love that kind of stuff. I'm deep into it.

I know you've said that you think Tuki is going to last for six books. Is the goal then to fill in all the blanks with fantasy?

I'm not sure I would put it that way exactly because that just sounds like I'm just making up a quick easy fix. What's important to me is that the reality that's established of the time period, of the real technology that was available and the fruits and the plants, and fire and multiple human species, I want that to be very real. I try to keep that feeling very real, but then to elevate the story, I'd like to put in the fantasy, not to cheat. Do you know what I mean?

But will you ultimately be explaining why there's only one dominant species in the end? Is that one of your goals with the series? We know that at the end of the day, there's only one species that survives.

Oh, yes. Yes. So even though I'm going to make up the circumstances that ignite that. Obviously nobody knows, or can ever know. But it'll be a good guess. It'll be entertaining. [laughs]

Your first version of Tuki was a webcomic. What was that experience like?

Well, it was kind of fun. I was able to just do something completely different from anything I'd done before, Bone and RASL, and even Shazam! I looked at other people's webcomics, Kate Beaton especially, because I really love her comics, and it seemed like there was a model. It seemed like there was a way to make some money. If anything, building a community and maybe selling compilations, or selling t-shirts or posters or whatever. So I decided to just go into it. But my cutesy idea was, I'm going to treat it like Prince Valiant.

In fact, I was at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum one day and I was visiting behind the scenes, and there was a cart where they were putting away pieces that people had asked to see. On top of this cart waiting to be refiled was an original [Hal Foster] Prince Valiant. He drew so freaking big. It was just amazing. I just looked at that and I was like, okay, that's what my webcomic's going to be. I'm going to do a Prince Valiant comic maybe once or twice a week. And I also thought that would be a good way to not have the crushing deadlines that I had for Bone and RASL. That wasn't true. That didn't make any difference, by the way. [chuckles]

Well, it's interesting because I look back at the webcomic version of Tuki and you seem to have approached it not in the Prince Valiant style, which always has a recap and then a cliffhanger on every page. You seem to approach it as more of a serialized comic book. Where it felt like the intention was always to release it in traditional comic form.

Yes, I wasn't actually really copying the Prince Valiant [approach], but I was in my own way thinking I'm just going to concentrate on this page. Yes, it's going to be part of a story, but I'm not worried about that story. I did try to do something that would trigger your memory and then leave you thinking what's going to happen next. But it didn't work, to be quite frank, and when you read them all together, they stop and start. Sometimes they flow, sometimes they don't. They didn't flow good enough for me. And I knew that I had a problem. This wasn't going to work this way.

When you were doing the webcomic version, how plotted out was it at that point?

Not enough. I was doing it straight ahead more. I have an ending, and I'm still heading towards that ending. And I had maybe one or two ideas that were not that thought out. I just jumped. I got out of RASL and I went straight ahead. I don't know if that's a term in comics, but that was a term in animation, where you just start drawing and you just go and find out what's going to happen. And that was not my style. It didn't work out.

When you decided then to reboot the series, you went back and you rewrote dialogue, you redrew and added pages. You also changed some major concepts and terminology. How did you approach it the second time around?

Well, I took quite a bit of time off. I did the comic strip, I think I started in the fall of '14, and then the last couple of strips appeared only in the comic book, which came out in January of '16. So it wasn't quite a year and a half of work. Then I was involved in starting Cartoon Crossroads Columbus, CXC, the cartoon festival in Columbus. And I just took my time. Nobody was clamoring for it. I was like, I'm just going to get this figured out before I visit it again. And I did, and I slowly worked it out. It went through a few iterations and I showed them to people. I showed them to people that I trust, and would get feedback. They would like something, and would push those, and just the normal process.

And then I finally ended up thinking, okay, this is the way it's got to go. It needs to be a little more real, and a little more fantasy. Strengthen both ends. And this was a big one, and this was actually my wife Vijaya's suggestion: I was using fictionalized names I made up for the different evolutionary levels of humans. I forget what I called them all, but I do remember that the Homo habilis, the Habilines, I called them the Dinka. Then I decided to look it up and there's an actual African tribe called the Dinka. So then I changed it to Dinga. Then I got uncomfortable with making up names and Vijaya suggested [to] just call them Pithecines and Habilines. That was an open-up-the-curtains-and-let-the-light-in moment. I had been worried about explaining what I was doing, and making it clear what this comic is about. Because it's very weird and no one's ever really handled this particular moment in history before. So that helped. That was just one of many little things that fell into place over a period of a number of years.

When you look at the current version against the webcomic version--

Don't do that, really. [laughs]

I think it’s great. I get a kick out of it! Right now I have two windows open with them side-by-side.

People do like that, and I understand and I love that kind of stuff. I understand it, but the art, that's the bad stuff! That's wrong. [laughs]

You get so much more room to breathe in the new version. If you're doing a serialized story, nobody wants a day of nothing. You're always under that pressure. So now you have these pages where you're allowing a journey to take place, and where I can read, I can flip the page three times to get from point A to point B. But in the webcomic version, it has to be super compressed.

Exactly. There was no way you could just say, oh, trust me, this will mean something in two or three days. [laughs]

In both versions of Tuki, including the comic book version, you've always gone with the horizontal format, giving yourself that widescreen layout. Was that the plan from the outset?

No, no. It wasn't really a goal or something I wanted to do. It was just that I thought to match the comic to the screen, because computer screens are landscape. So I just did that, and then when I wanted to [redo] it, I had 70, 80 pages that I drew the shit out of. I didn't want to redraw those! I had talked with Tom Gaadt, who works with me here and he does a lot of Photoshop. I was like, is there a way to recut these or reshape them? But there wasn't. So I was like, okay, I'm just going to keep this shape and work with it.

I came up with this way to do the comic where I would launch it with a larger establishing panel and then you could flow from there. And that was a tricky thing to use on every page. That was one thing I could abandon right away. Then I could start just doing regular pages even though they're horizontal.

Well, it's interesting because it being a story in Africa, you have the real estate to do these wide vistas now.

That's true.

But that was never your goal?

That was not a goal, but I knew it was happening and was there to be used once I got going. That's why I printed it large as well. Bone, every time it got reprinted, it got a little smaller. Its ultimate version is the Scholastic books which are very popular, but they're smaller than the original comic books. Even RASL, I gave in and started making those the size of regular books, but this was Tuki. I was like, you know what, I'm not doing that this time. I'm going to make this a big honking, fun comic book. I want it to lay flat. I want it to feel proportional to when I was 10 and reading a comic book.

When you brought back Tuki, you went the Kickstarter route, which put you 100% in charge of every possible decision. You didn’t have to worry about any market consideration or shelf space. Was that a draw for you?

Sure. I didn't know I was going to turn out to be good at it, but Vijaya and I have been self-publishing since Bone #1. We've never thought about anything other than what makes this issue fun for us. We never did any merchandising that we didn't want, you know what I mean? We never did wastepaper baskets or anything. We always did little statues or t-shirts or things that we wanted. We've always been that way. RASL, the same way. We didn't even shop RASL around. We just did it.

So we thought, well, okay, we'll try that. We were a little unsure at first, but we gave it a shot, and did experience this direct communication with readers. As opposed to normally, you have to go through a distributor, you have to go through a publisher, you have to go through a comic book store, a dealer, somebody who's selling the comics. Then, if you’re lucky, you get to talk to some people at shows or whatever. We were overwhelmed by thousands of people buying the book, ordering the books, and asking questions, like from Russia. From Germany, Brazil, all over the world. It was crazy.

And everybody was so excited and happy about everything. Even though it was a train wreck in terms of how much work we made for ourselves, it was a really wonderful experience.

One other thing about the webcomic and the Kickstarter versions though is the Kickstarter version is black and white. Do you miss the color? RASL also came out in both black and white and color versions. Is that something that you eventually see yourself revisiting with Tuki?

I do see myself revisiting Tuki in color, but I don't know that for 100%. Bone and RASL both started off as black and white. Then we switched RASL to color for the collected version. And I love the color so much. Done by the same guy who had colored Bone, Steve Hamaker. That was to me-- that's the version. I didn't even need the black and white one anymore. Bone–the color Bone–I like, but to me it did not replace the black and white version. So I worked it out with Scholastic that they would license the color version and sell that. And then Vijaya I would continue to publish the black and white, the big one-volume edition. With Tuki, I decided this is not a webcomic anymore. We're now turning this into one of my comics, and it's going to be black and white at first.

When you did the webcomic version, was the thinking it's on the internet, therefore it should be color? Was that part of the consideration?

I guess it was because we had just done RASL in color, and I thought oh, well maybe we're just going to go color now. It's a lot of extra work to do color! [laughs] I've got two graphic novels I want to crank out in less than a year, or about a year. That'll save me some time. Plus I just like black and white. I have to admit it.

When you start on a project, does the audience factor in? Do you consider Tuki closer to Bone than RASL? Because RASL is a much more mature book. Was that ever a consideration?

I wouldn't say it was. It was in this way: I was always in love with what we've mentioned - Hal Foster, and Prince Valiant, Peanuts, Pogo, The Phantom. I loved comic strips, dailies, and Sundays. I am a huge fan of Chester Gould and Dick Tracy. It used to be hard to read old comics. I remember this book came out in the '70s called The Celebrated Cases of Dick Tracy, and it had all this stuff from the early days - the hot stuff was like from the '30s. Gangland murders and kidnapping. You read that stuff when you're a kid, it was hardcore, and it was in the newspaper! It was not hiding anything! Squeamish stuff! There was torture--

I don't know if you've read any of the Floyd Gottfredson Mickey Mouse strips, but there’s all kinds of shocking stuff in there, like suicide and murder.

Yes! [laughs] But anyway, I never thought that the newspaper strips were just for kids. They were always meant for the whole family. Everybody reads a newspaper. Dad, mom, the kids. My only thing was just trying to do something that could be in the paper. Bone is not like, completely safe and unscary. There's parts of it that get a little hairy. I've had plenty of people tell me that their kids have got too scared and had to stop reading. And then they come back to it, so it's all good.

To me, the guardrails were: what could run in the paper, when I was reading the paper? That's it. I never say fuck or shit, even though I swear like a sailor in real life. Schulz never swore. Walt Kelly never swore. Hal Foster never swore. Milton Caniff never swore. They could do it, I can do it. That was my attitude. I think RASL could have been in a daily strip. There's a little bit more nudity, but it certainly could have been on HBO easily. That's basically my thought. I'm not for kids. I never pull anything back because I'm afraid, “Oh, kids will not like it.” Kids can take it.

It's interesting because as I mentioned, I went back and looked at your previous big Comics Journal interview. That was 1994.

Oh, that was the first one.

The first one. So that was pre-Disney Adventures. That was pre-Scholastic. I don't think you had even done the Image Comics thing yet. I think at that point, you were still primarily a self-publisher. And I think in those days, if you had told me that Bone was going to be the comic that really cracked the middle grade market, I don't know if I would have believed it. I don't think you would have either! Were you surprised that it was accepted so massively by Scholastic and by a middle grade audience in particular?

So my point of telling that story is, by the early 2000s, we were encouraged that Bone could be published by a New York publishing house. So Vijaya and I got a literary agent, and we went to New York and we actually spoke with six publishers including Scholastic. But it was still too soon. No one was interested. Not even Scholastic was interested. Maybe we planted a little seed, I don't know. It was basically, “Well, thank you, we will call you.” They never called us. None of the publishers did. They just didn't know what to do with it. They obviously knew about it. They knew what the sales figures were like, they knew that kids were reading it. They knew the librarians liked it. But like one publisher suggested, well, why don't we refigure it so that it's one page of prose and one page of illustration? And I was like, that’s a Big Little Book. This is not a Big Little Book.

This is a comic book. That’s 12 years of work, man. I'm not going to go redo any of it. So yes, in a way, we still thought this could work, that a tipping point was coming, but even so, a couple of years later, when Scholastic called and we worked out a deal, we were-- I think Scholastic, and Vijaya and I, were kind of amazed at how big it went, how fast. And the crack it opened up. I mean, Kazu Kibuishi and Raina Telgemeier jumped right in there. Oh, and so many people. I mean it's just become the most wonderful-- I couldn't be happier. This is exactly what I wanted comics to be!

I mean, you won, right? There was an article I was looking at recently that said, 17 of the top 20 comics now are for younger readers.

Yes, well, it's the biggest, fastest-growing segment of all books. It's a thing. Comic Scene recently did a history of comics and they were talking about [Bone] saying it changed everything. It was the first big multimillion selling YA book and everybody has to turn around and take a look at that, you know? Well, I'm thrilled, because I think everybody likes cartoons, man. Everybody likes cartoons!

Well, speaking of librarians, there's a really lovely story in Bone: Coda, where you say you were saved by librarians. Did Cartoon Books really almost fold right around that time?

Sure. We were publishing other people, and that didn't work out and left us holding the bag. We were doing all the toys. Toys were big. We had a lot of money tied up in those-- I forget all the circumstances, but we got caught with our pants down and were exposed financially. We weren't quite sure if we were going to make it. We tightened our belts. We paired down Cartoon Books to just Vijaya and I and Kathleen Glosan, who’s been our production manager for nearly 30 years now. And the three of us, we just shut down the office. We moved into the studio above my garage. My little one-room studio. But the way that librarians saved us was by buying Bone! This is before 2002, and our books were going crazy in libraries. But we didn't know that.

It turned out that graphic novels in general were picking up steam, which even though graphic novels had been around for a while, they [didn’t] really get going until the mid to late '90s, right? When, for the first time, we were starting to put books out that were meant to be restocked. Before that, graphic novels were, with the exception of like, Watchmen and Maus, or even the Cerebus graphic novels-- before that, they were just like specials, like a collection of special Silver Surfer--

Those Marvel graphic novels, right?

Yes, exactly. They were all hardcover and expensive and nobody reordered it. And so things started changing. Having a spine made a difference to librarians. That actually mattered. And the other thing was that Bone was something they could put on a shelf next to Maus. That's what I heard a lot anyway. This is “one of the first things since Maus that I could put on the shelf.” And I didn't know that that was happening.

One of our other adventures, like going to New York or talking to publishing houses, was when we tried to get into Baker & Taylor’s catalog. They distribute to libraries. That door just got slammed in our face. No comic books, no self-published books. That was just a no-go, and our first hint that something new was going on was when Baker & Taylor called us, a few years later, and wanted to start carrying it. And Vijaya asked them, why? We've been trying for years to get you to carry us. They go, the librarians are demanding that we carry your book. And then it was shortly after that, that the librarians told Scholastic, you need to start publishing this because we need more of it. So that's how librarians saved our books.

Well, one other thing about librarians, since we're on the topic - Bone made the top 10 Challenged Books list in 2013.

Yes, and it doesn't always make the top 10 list, but it always makes the list. There's a picture making the rounds right now. Have you seen that on social media? I don't know the source of the photo so I can't tell if it's a library or a bookstore. It's probably a library. It has banned books and it's a lovely shelf. Some of my favorite books.

Oh, yes. I have seen that.

Oh my gosh. Oh man, it has a bunch of graphic novels, but it's also 1984 and Huckleberry Finn and Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. I mean, it's amazing. It's just amazing, and Bone is super-visible right at the top of the picture.

What is it that people have found offensive? I mean, I know there's a cigar, right?

Yes, that's tobacco and alcohol, which I just, I don't care. That's life. It’s a vaudeville prop.

I mean, Uncle Scrooge always had one too, right?

It was Peg Leg Pete who always had a cigar.

That's right, yeah.

He's a bad guy.

The bad guys always have one.

Yes, well, that was my argument too, with Scholastic was like, Fone Bone and Thorn are the good characters and they never touch a drop of alcohol. They never smoke. It's all the grown-ups and kind of the bad characters, like Phoney Bone and Smiley. And [the challenges were] also supposedly [about] political viewpoint and violence and racism.

Is there a political viewpoint in Bone?

All the books I love, and pretty much all the books on that bookshelf that we were just talking about have a moral point of view. Now, whether you want to say that's political or not, I don't particularly think it's political, but yes, there are messages of-- questioning authority, don't believe everything you're told, trust yourself and trust in your friends, and there's messages like that I am proud of.

Those don't seem terribly political or radical in any way, shape or form.

Unless you don't believe people should be allowed to question authority. If you think people should believe what you believe and what you want them to believe, then yes, there are people like that and they're pretty active right now.

I have a hard time thinking of any work of literature that says authority is great and you should follow it.

There isn't one. People that want to ban books are not the good guys. [laughs] There are no books about those guys.

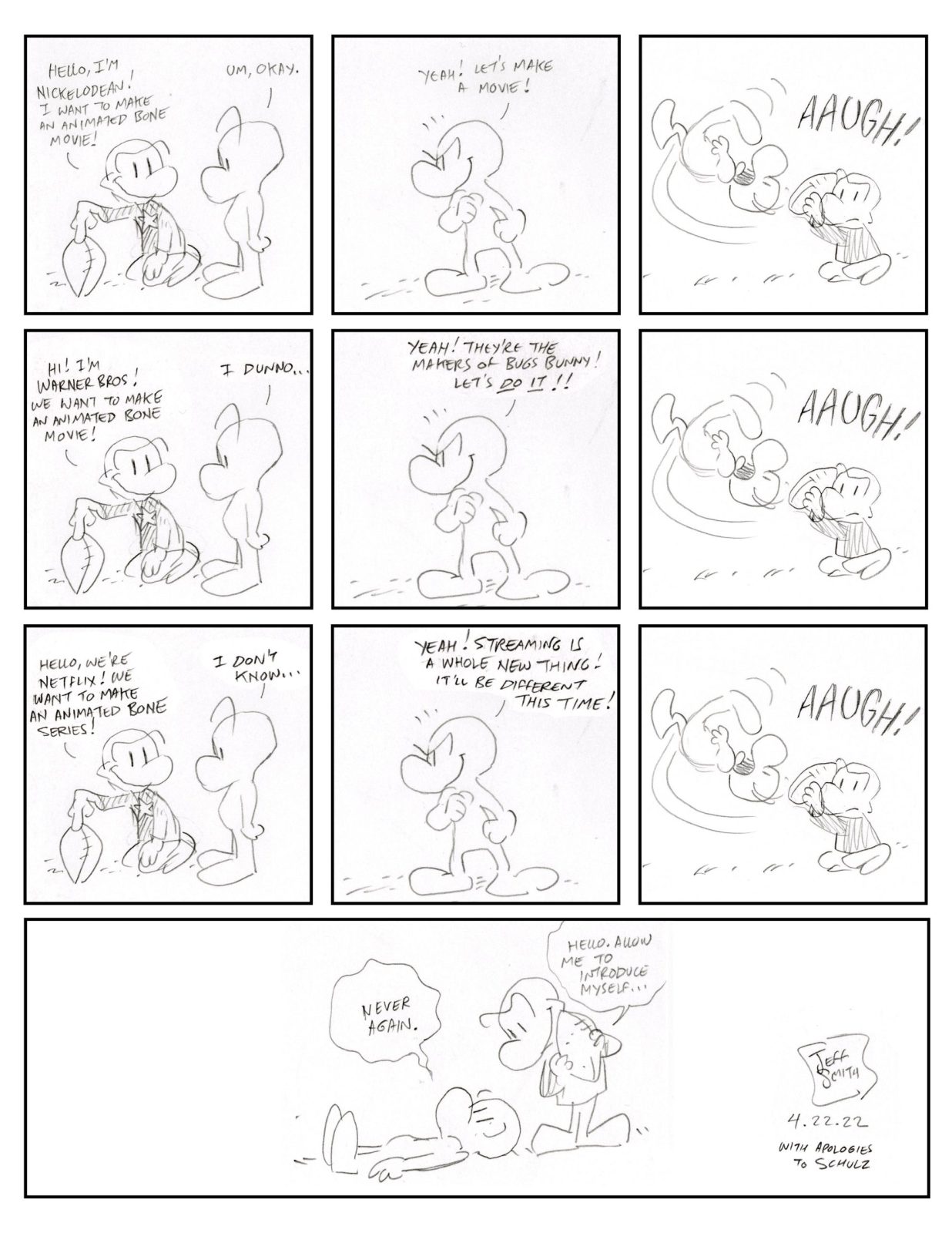

Speaking of Bone, I would be remiss if we didn't talk about the cancellation of the adaptation from Netflix. When did you find out? Was it before, hopefully, the announcement?

Yes, I actually found out before Christmas, but it was a weird situation. It was a very quick meeting. We didn't have a lot of warning. The decision was not very fully explained or spelled out. We had a very small staff. We had just gotten up and started. We were just starting to gel. I really wish we'd had more time. I had two people that were really running it, Kat Morris and Nick Cross, both come from Adventure Time, Steven Universe. They really got it and they were breaking up the story in really good pieces. They knew Bone really well, but they got let go right before Christmas. And like I said, it was an odd situation because at the time, Netflix didn't make any announcement about it, and they still own the rights, they hold the rights to Bone.

So I wasn't going to make an announcement. Why should I do their work for them? I don't know what's going on. That was an awkward situation and I was actually relieved when it finally came out. Not only because I didn't know what to say about it, because I get asked about it in every interview, but also because it turned out it wasn't just Bone, it was like freaking everything. They were just chopping everything. Netflix was having its own problems.

The one silver lining was that-- the article that did finally break was not about Bone. It was about all the troubles they were having, the stocks slumping, subscribers drifting away, all the upheaval at the executive level and they're just axing everything. That's what the story was about, but almost every news outlet used Bone as the main image or the headline was about Bone being canceled. That was everybody's takeaway from it. The reaction on social media was gigantic. Shock and anger. That made me feel a little better. At least people cared.

And then you posted that amazing strip on Twitter recapping all the different attempts at adapting Bone.

Yeah, and some people were like, oh man, don't feel bad. Well, I don't feel bad. I feel embarrassed. I feel like Charlie Brown. I keep going back to kick that fucking ball, and they keep pulling away. [laughs]

Is part of the problem in adapting Bone, that same thing we touched on earlier, that it's hard to classify, and it's hard to say 'this is the audience for Bone,' even though, at this point, you have generations that have grown up on it?

At least two, if not three. In 30 countries! I just don't even know why I have to explain it anymore.

I guess if you were to hand Bone to an executive somewhere who had never heard of this thing and didn't have kids who grew up on it or anything-- I don't know how to explain Bone to somebody who's never heard of it.

I don’t know. So when the decision came down, I wasn't invited to the meeting. I’m just the creator and executive producer. Why would you want me there? I asked my team, what happened? Who was there? Who were the executives? Because I never knew anything about the new head executives at Netflix. I never spoke to them, and I don't know anything about them. What I heard was, oh, we don't know who they were. The Zoom meeting started, there were no introductions and they said-- go.

And at the end, they said, “Who would want to see that? I don't get it.” That's it. That was it. That's all I got. I mean, that's my understanding of the whole thing. They were looking for something that, as was written in that original article, they're looking for some stuff like Boss Baby. Well, I'm not going to give you Boss Baby. [laughs]

Do they still hold the rights?

They still hold the rights, yes.

So I'm sure you're getting phone calls then, but you just refer them to Netflix?

Yep. Now you understand why I drew the comic. [laughs]

I also saw on Twitter you're working on a new Bone story.

Yes. I've got a book, due into Scholastic this summer, and it's called Tall Tales 2. It's a series I started because Scholastic wanted more Bone material, and I still like drawing the Bones. I didn't want to never draw them again. I wanted to come up with something that I could do that wouldn't be mistaken as a sequel, per se. I didn't want to do a 1,350-page novel. So I came up with this idea of Tall Tales where Smiley Bone and Bartleby will take these three scouts out camping, and they'll sit around a campfire and tell stories. I had a few orphan stories that didn't really fit in the big Bone one-volume.

I was able to use that to put little stories like that in. We made up some new stories about a Tall Tale character named Big Johnson Bone, who's actually in the Bone canon as the founder of Boneville, but I never had any stories about him. So me and Tom Sniegoski made up some stories for the first Tall Tales. The second one, it's the same idea. I have a couple of orphan stories to get rid of, and Tom wrote three more short stories and we got some other artists to work on them.

That actually brings up something I haven't really heard you comment on before. For an independent creator, you've collaborated a lot with others. Tom Sniegoski is one, Charles Vess was another. Do you enjoy collaborating on your own creations like that?

Sort of. I love collaborating with them, but then once the collaboration is done and I had to do all the drawing, that’s not so much fun. [chuckles] That's not true. That's not true. I had a blast. But, it's not that it wasn't fun, it was obviously fun, especially with Tom and Charles. Tom is just literally one of the funniest people I know. So just being on the phone with him is like a piss-your-pants session. He just makes me laugh so hard.

When I'm on the phone with him and there's other people in the office or whatever, they all know when I'm on the phone with Tom because I'm laughing out loud upstairs. And the same with Charles, because he's such a good friend and he's so knowledgeable about fantasy, that deep symbolism side of it, and it was just a real joy to work with both of them. In the end, though, I still find it more engaging to do both levels of it, to come up with the idea and the writing and the pictures and all that. That's really where I'm at.

Are there other collaborations you've considered or somebody else you'd like to team up with but haven't had the right project come along yet?

Yeah, there's actually one bubbling up right now. It's way too premature to say anything about it, but I think it'll be fun, like one of those projects.

Just to wrap things up, as a creator, who's still experimenting with the form–you've done Kickstarter and you've done a webcomic–you've done all these different formats. Where do you think comics are? Where do you see things going?

I think they're going in a really good direction and I think they're in a good place. They are exactly where I think we all were hoping [they would be] in the '80s and '90s, and they're there. Of course, they can go deeper and they could have less people hating on them. But I actually think that pushback that we're seeing is indicative of the success and the penetration that this form is making. It's quite upsetting to some people.

Is there another format you could see yourself trying?

Well, obviously, I love animation. Or are you talking about with comics?

With comics, but certainly if there's another medium.

Well, that's all, and I'm pretty much near the end of bothering with animation, but for comics, I don't know yet. I don't know. Obviously, if you look at my work, you know I don't like to repeat myself, so we'll have to see, and I don't know what it'll be. I didn't know Tuki was going to be landscape. I didn't know I was going to try a webcomic next. I didn't know I was going to have to figure out new widescreen panel layouts for RASL.

I made all the panels in RASL stretch across the pages even though it was a vertical book. All the panels were horizontal because I was trying to-- I was really into noir and I was just kind of aping that cinematic style, which I would take to the next level with Tuki. I don't know. I don't know what the next one will be until it gets here, or it's a little closer anyway. [laughs]