I spent my holiday free time leafing through a stack of Nemo: The Classic Comics Library. And Comic Book Artist. My stash of The Comics Journal was buried underneath too many boxes to get to easily. Sorry, Gary.

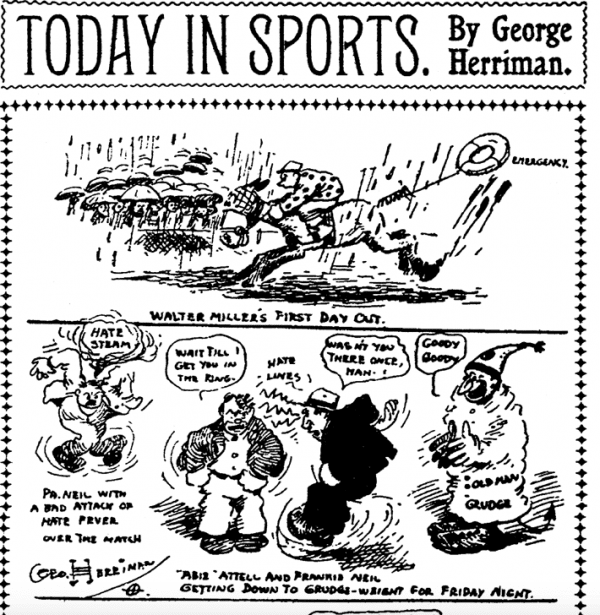

I was doing some research on the C.N. Landon Correspondence Cartooning Course from 1909 and stumbled on to something I did not know: George Herriman may have produced a "daily strip" in 1904 even before they were, as some claim, "invented" by Bud Fisher around 1907. And what's more: both started on the sports page of the newspaper. Bill Blackbeard reports this "startling discovery" in Nemo #1 from 1983. It's a great essay. Track it down if you can find it.

Did you read John Kelly's piece on one of the longest running comic strips that lived on the sports page? It's interesting to me to be reminded of comic strips' early association with gambling, generally slumming it on the sports page for laffs with the masses. That connection also makes me think of the web and all the possibilities of being visible on the front page or the sports page of a newspaper then and now.

Back in 1905, cartoonists were often expected to basically find interesting ways of staying employed by the newspaper. Daily strips didn't exist yet and Herriman and Bud Fisher and apparently, originally, Clare Briggs were just trying to find ways of stringing together gag bits and repeating characters day to day to fill space around the horse track listings and baseball box scores. Bill Blackbeard expertly emphasized this and organized the timeline which unearthed this bit of Herriman trivia which was, in 1983, new. Blackbeard likened it to finding an earlier draft of Marcel Proust's Remembrance of Things Past (!) and lamented that no one seems to notice or care anymore about Herriman because he'd been written about enough.

I must admit it is fun to think about those cartoonists 100 years ago just trying to figure it out. Herriman was barely 20 years old and floating from paper to paper and city to city. He would just fill the space leftover after they laid out the paper--much like Lynda Barry did in issues of her college paper and later The Rocket. This idea of jockeying for space in the paper reminds me of seeing comics online in the context of some non-comics website or platform. For example, when I see a Kate Beaton comic floating around on various websites and platforms and seeing non-comics readers absorb it I'm reminded of the slow evolution of the comic strip in the newspaper. When I see a Sam Alden illustration for the New York Times and it reads like a comic and then see one of his Tumblr comics sandwiched in between dog gifs it reminds me, daily, that the landscape is changing fast.

Webcomics haven't totally been defined, but the fences are in place, and within that playing field the rules and regulations are starting to take shape. There are so many different types of webcomics (and what can be loosely defined as Tumblr comics) and how they fit into our daily consumption of online content. I feel like they fit into a very similar arc of history to that of the early comic strips; if the two arcs were mapped you could overlay the two maps like transparencies and see the similarities.

This honestly excites me,because I feel like maybe comics--and specifically serial comics--can work their way into the fabric of our lives in a way they could not before. Notice I didn't say "work their way BACK in." I think it's better now than it was then. The story of the demise of the traditional print newspaper comic strip is another story. Imagine "being in the newspaper" a hundred years ago. What that meant. The potential. And imagine the stress and the strain on the cartoonist. It was a tightrope act just to stay employed as a cartoonist. And now everyone is "in" the digital newspaper of the internet every day. Of course it's not the same, but stumbling upon this article about Herriman throwing darts at the wall reminds me of Kate Beaton, Ed Piskor, Jesse Moynihan, Meredith Gran, and scores of others who have found a way to make "being in the newspaper" payoff in some manner or another. The stories of both arcs, from both eras, rhyme.

Michael DeForge has this great riff when the conversation inevitably turns to "the kids not knowing their (comics) history." He says something to the effect of, "I feel like we're all in these punk bands and we all go to punk shows and then we go home and we're supposed to study ragtime music." Meaning, the idea that younger cartoonists are expected to read the classics is silly. Maybe some but not all. Like Tom Devlin said somewhere,"No more talking about EC Comics." Meaning, again, that young makers don't need to hear it from the old guard about what's what. It's a good point and well taken. However, I like to think there are more links to be explored between cartooning today and 100 years ago. I thought I knew the early history of the comic strip like the back of my hand and just from rooting around some old magazines about comics from 100 years ago I found a map for the present day. Felt that way to me anyhow.

I asked my editor and comics scholar, Dan Nadel, about this occasionally quoted sentiment of younger makers towards older makers and he said, "Here’s the thing about 'knowing your history' (you can quote me): It’s soooo easy. It’s a short history, there’s less than like 50 essential works that would take you about a week to digest, and, y’know, if you’re ambitious as an artist in the sense that you care about making good art (as opposed to making books, making Twitter, making a persona etc. etc.), it’s useful to know what was done before you in the medium of your choice. Only in comics (seriously) can one find a streak of self-hatred so strong that people would proudly talk about not knowing the history of the medium. You’d never hear that from a serious painter or writer because those people need to succeed in a context that does not value simple affirmations and basement festivals as a means of emotional survival. Basically, of COURSE plenty of people are not going to like Crumb or hate Chester Gould or not 'get' Julie Doucet, but you have to at least know what you’re dismissing before you just walk away. Anything else is just laziness, which is, except in very rare cases, not good for art. The difference between punk and ragtime is that they’re two different genres of music. The difference in genre between Michael DeForge’s comics, Crumb’s comics, and Herriman’s comics is basically negligible. Yarn-spinning emotional narratives that involve fantastical elements. See? I have yet to meet a good, ambitious cartoonist who doesn’t value the history of the medium."

Thanks for reading.

Over and out.

**please note that the Herriman strip shown above is from 1908. The ones Blackbeard is referring to in his Nemo article are from 1904.

***also please note that Mr. DeForge knows his comics history very well and values it very much. I just liked using his comment to echo a sentiment I often hear in our circles.