What is Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Last Ronin about? I don’t mean in terms of plot, that one is pretty simple. It’s one of those grim post-apocalyptic alternate future worlds that comic books love so much; a single surviving mutant ninja turtle1 sets out on a mission to assassinate the tyrannical ruler of New York, the man responsible for the death of his family. That’s not a lot of story, and much of it is cribbed from a thousand other science fiction and superhero books;2 it certainly feels thin when spread across five issues of 48 pages each. But what is this story about, beyond the things that occur on the page - what is it trying to tell us about the world?

You might think I am asking too much of The Last Ronin, another take on the well-worn story of the other mutant comics juggernaut of the 1980s. I would disagree. Ever since their unlikely original success, the Turtles have proved surprisingly adaptable in their popularity. There’s been several iterations of the comics series. There have been many cartoons and movies, and there will probably be more. Each time, surprisingly, the franchise has managed to have a point of view. Not necessarily an intelligent one, but a point of view nonetheless.

The original Mirage series was a grimy lo-fi affair that featured a nightmare New York straight out of a Cannon movie. The Archie-published Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Adventures found its own quirky niche in stories that often pushed the comedic tone to the forefront.3 The latest IDW run (of which I have written previously) ended up, under the guiding hand of Sophie Campbell, as a really interesting science fiction piece about trying to build a new society and adapting to change (physical as well as mental). As a concept, TMNT turned out to be surprisingly flexible. Even though many stories and characters return ad nauseam across various incarnations—Technodrome here, a Fugitoid there—the sandbox is big enough to make it worthwhile. Just throw an interesting enough creator at it and watch them do their thing.

No one could’ve imagined it would be so, the original creators first and foremost. TMNT wasn’t made to last, but it did. As Kevin Eastman noted, the first issue made good money off its 9,000 copies, but not enough to live on: “After paying my uncle back and all the other bills, it was maybe a hundred bucks, two hundred dollars profit-wise we split. Maybe a little more.” But then issue #2 got orders for 15,000, and re-orders of issue #1 were more than triple the original. It was one of the unlikeliest success stories in comics.

All the more more unlikely considering that the original Mirage comics aren’t very pretty to look at. Those issues were closer in artistic sensibility to the underground movement than the Daredevil and X-Men comics that inspired them. Eastman’s & Peter Laird’s drawing almost seemed more akin to Spain Rodriguez than John Byrne - as crude and rude as a turtle in a red bandana. It worked for them, though; that was the charm of that series. There was something oddly attractive about the ‘ugly-beautiful’ style of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles - the way everyone, not just the mutants, appeared twisted and broken. The grittiness of the world it described was reflected in the style it presented.

That style hasn't changed or evolved much since those halcyon days. Possibly Eastman & Laird knew what their audience wanted; possibly they were forced into managerial roles too soon to let their style develop.4 You can see some more recent Eastman work in issue #21 of the IDW ongoing series, from 2013. It’s slightly more polished, in that the lines are less scratchy and the panel movement feels smoother, but these pages mostly could’ve been lifted from his time on the original series... with the caveat that Eastman's style no longer fit the story the IDW series was trying to tell (and the colors don’t compliment it very well).

Eastman sold off his share of the Turtles way back in 2000, but somehow he’s still the only one of the original pair who’s been involved in the comics side of the business over the last decade. Laird has kept his ownership and his distance. Until The Last Ronin. Finally, the two original creators are back!

…except, it’s not really a return to ‘the glory days’. Because there never quite were glory days. The creators' indie rising stardom, as previously mentioned, was the briefest of burning candles - Eastman & Laird weren't Lee & Kirby on Fantastic Four, or even Simon Furman and Geoff Senior on Transformers. Also, The Last Ronin is not Eastman & Laird. It’s Eastman & Laird & Tom Waltz & Esau Escorza & Isaac Escorza & Ben Bishop & Luis Antonio Delgado & Samuel Plata & Ronda Pattison & Shawn Lee. Already, before turning to the first page, The Last Ronin feels closer to the modern, more professional Turtles approach.

Which isn’t a bad thing; I like these modern comics. They give me that soap-opera-with-punching buzz superhero comics used to give before their universes got overcomplicated and self-involved.5 Reading this series really felt like reading another one those; besides the occasional Eastman-drawn flashback scene, The Last Ronin looks like a typical IDW Turtles story and is written like a typical IDW Turtles story. Except it’s long. It’s so damn long, 250 pages for a rather generic dark future storyline of the type the X-Men burn through on a weekly basis.

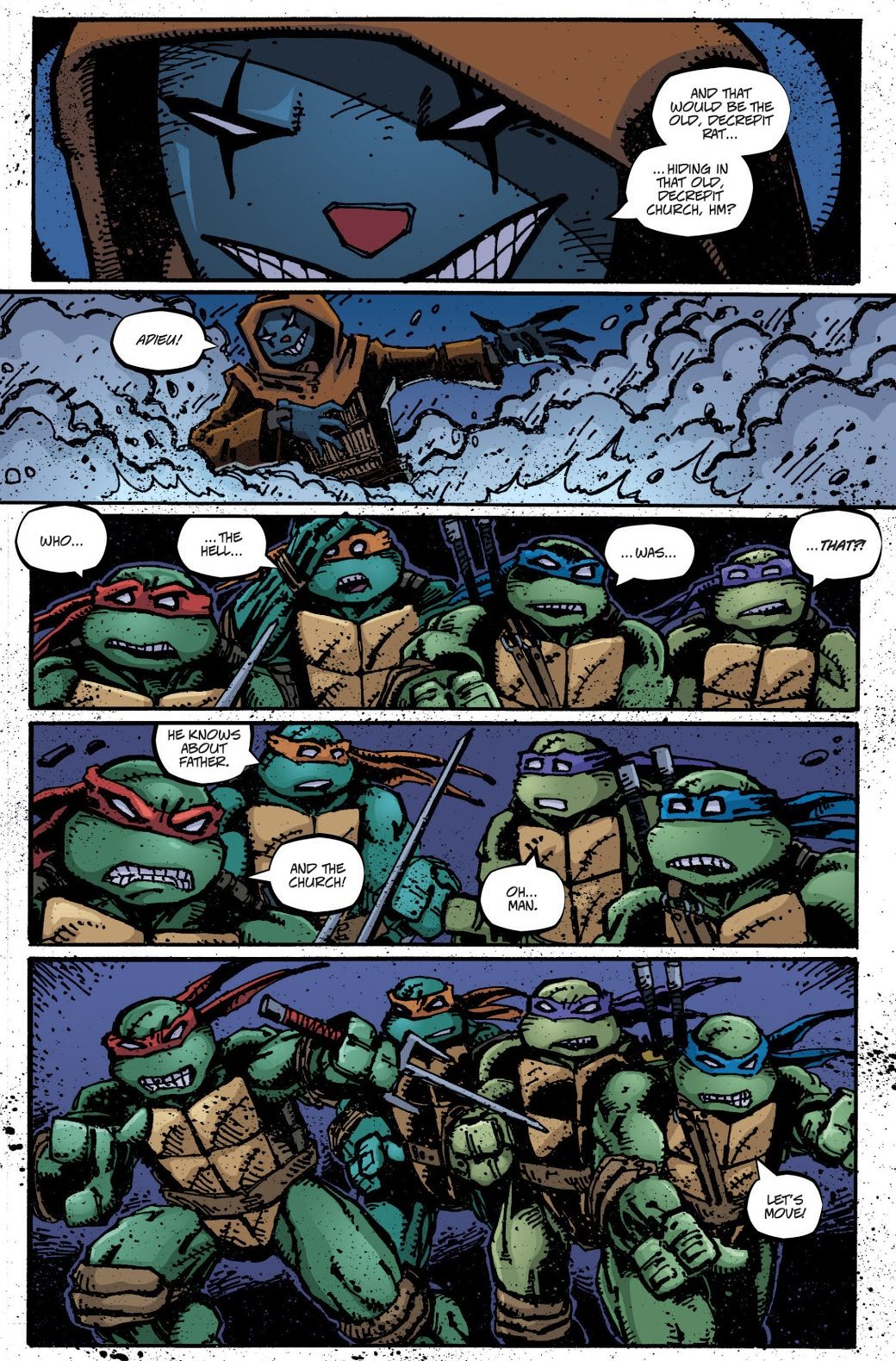

There are just about zero surprises. At least, I hope the story doesn’t think we are surprised when it turns out that the our point-of-view turtle is the lone survivor of the group, and the other three who talk to him are ghosts in his mind (it’s called The Last Ronin after all). I guess the idea that the last survivor is Michelangelo, the ‘party dude’ of the group, could be considered a mild twist - but he’s already a dark and tormented soul when the story begins, so it doesn’t really matter which one of them he was. He doesn’t end the series in triumph by reclaiming the goofy side of his personality; he ends it by beating his enemy to death in a mud hole.

As previously mentioned, references to The Dark Knight Returns come thick and heavy - our hero even gets a Robin figure. The Last Ronin, however, lacks everything that made Miller’s early work interesting: his Gotham was a place of people with clashing ideologies, its large page count utilized to explore how the person-on-the-street reacts to the Batman’s reappearance. The Last Ronin, despite being even longer, doesn’t really show ‘average’ life in this futuristic New York; there are the good rebels and there’s the evil Foot Clan that rules the city, led by a nonentity named Oroku Hiroto who mostly spouts clichés about being a god.

When Hiroto is finally defeated, there isn’t any sense of how the city is meant to function; what do citizens other than our protagonists feel about him? What is his relation to rest of the country? Is New York meant to be some independent fiefdom? Is there still a President? You can ignore these kind of questions in a shorter story, or you can supersede them something more interesting. But The Last Ronin has nothing to offer in exchange. There’s no sense of place and time for this story, which is particularly shameful considering how much the original Eastman & Laird comics felt of their particular moment.

What about the history of the franchise? Surely the creators have something interesting to say about the way the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles have changed throughout the years - from self-published success story to a child-approved multimedia franchise? Eastman sure seemed reticent about his overnight success in that big interview.6 There’s a hint of something interesting in the idea that Michelangelo is still mutating, getting bigger and stronger (the way the franchise did) while also taking a more monstrous appearance; or the idea that being close to him all these year affected the DNA of his human friends and mutated them as well. 7

The whole TMNT phenomena has indeed mutated beyond the creators’ control, and it has affected the lives of their friends and coworkers in some unfortunate ways. They became closer to the Shredder, the bosses in their corporate lair than to the original downtrodden (literally living-in-the-sewers) protagonists: “Every day, the drawing board got further away,” Eastman told TCJ, “and there were a million issues like trying to put more real corporate structure to this organic thing.” So you could do something with that, in theory. Yet The Last Ronin steers far away from that territory, from anything that is not goodies vs. baddies. There’s nothing to it besides what you see on the page.

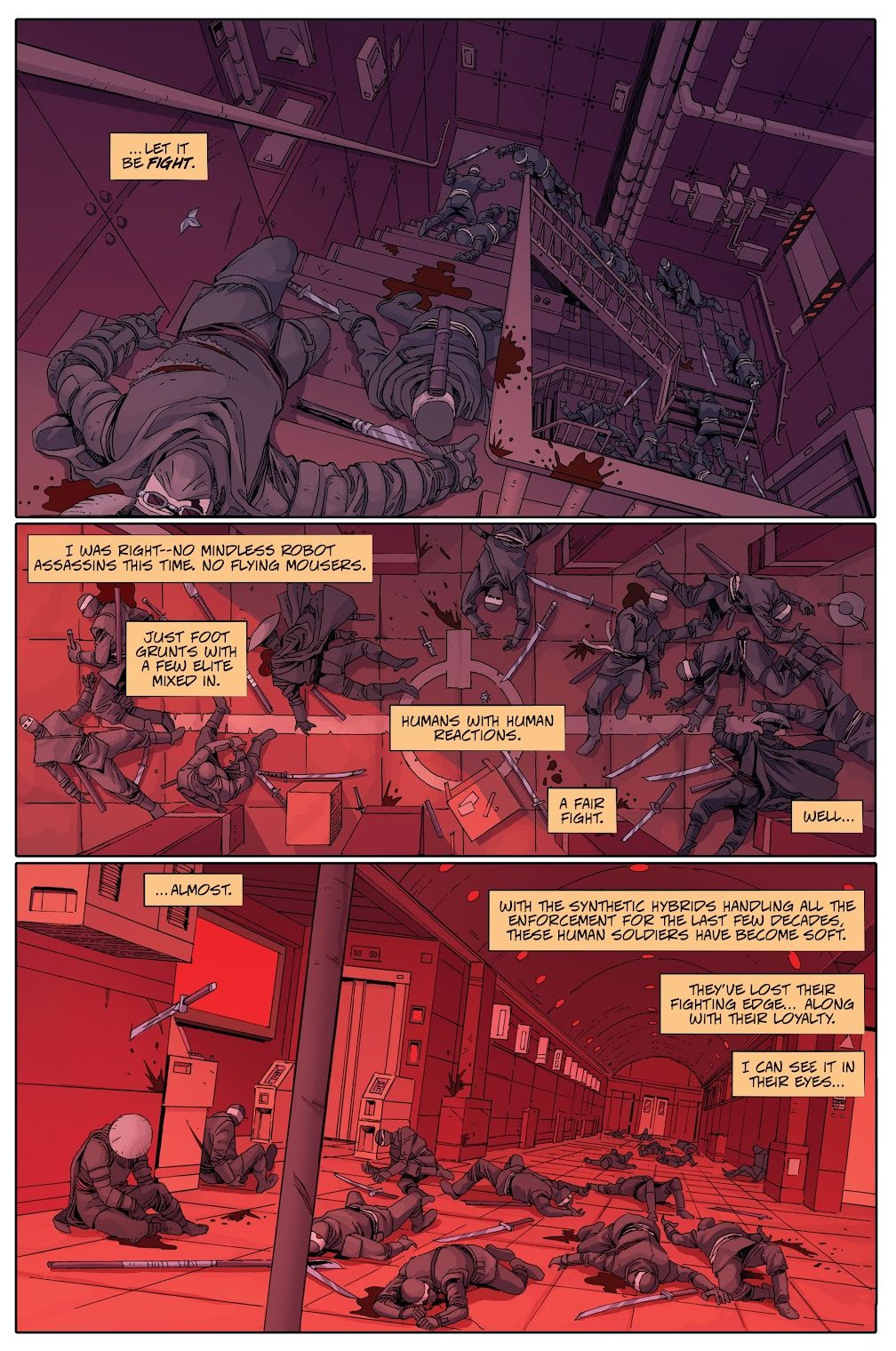

The pages you are seeing here are mostly the work of Esau & Isaac Escorza (who took over from the original intended artist, Andy Kuhn), working over Eastman’s layouts. I haven’t encountered their work before. Esau, at least, has some credits in Heavy Metal magazine, which should bode well for an over-the-top story involving mutants and ninjas (and ninja mutants) in a futuristic setting. And when it comes to the content of The Last Ronin - they are fine. Ok. It’s perfectly competent stuff.

I can say the same for Luis Antonio Delgado’s colors and Shawn Lee’s lettering. They all do what they are asked to do. It’s just that what they are asked to do is pretty uninspiring - lots of browns and dark shades of green. The whole affair is rather pedestrian in terms of layouts, and the choreography can be overtly chaotic without the sense of proper weight and mass to the action. Combining Eastman with the Escrozas produces neither fish nor fowl - it's certainly absent Eastman’s original grime.

In all, The Last Ronin lacks any memorable element. In issue #5 we learn that people are turning to looting after the robotic police are taken offline. It’s an oddly conservative message for a story all about bucking authority; looting is certainly presented as something bad and irresponsible. Worse - it's presented in such a bland manner. All of one panel is dedicated to faceless people rushing through a mostly empty street; one car is tipped over and somebody is carrying away a cardboard box. There’s no actual sensation of the lawlessness the script calls for (indeed, our protagonists wade through the masses with little effort), which is another outcropping of the story’s failure to establish a sense of the city. If we didn’t see it fixed, we can’t understand what it means when it is broken.

Look at the big final fight, which the first four chapters have built up. It takes Michelangelo and villainous Hiroto through a series of different locations: an office building; the street; the sewers; and the aforementioned mud hole. What’s meant to be a brutal fight, with Michelangelo slowly losing steam, feels like a mostly weightless affair; the two combatants are like toys being thrown one against one another. Compare it with the original fight with the Shredder in the first issue of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles from 1984, with its comedic slaughter as the four protagonists gang up on their foe and cut him to ribbons. It was mean, and it was fun because it was mean. And exaggerated. And crude.

The Last Ronin is a series that aims squarely at the middle. It probably has all the right boxes ticked to make the old fans feel happy, which is exactly what makes it so disappointing: it has nothing new to offer, in an era when some Turtles comics are producing their best efforts. You might’ve come in for a blast from the best, but you’ll end up with barely a fart.

* * *

- The ‘teenage’ part possibly no longer applies, though considering how long-lived some turtles can be I guess a decade and change doesn’t amount to much.

- Frank Miller’s Daredevil was a significant influence on the original Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles run; this story mines both his Ronin and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns.

- Personally, I would highly recommend searching out Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Adventures Special #4 & #8, drawn by Milton Knight - a master of the exaggerated take and the cartoonish overdesign, who seamlessly bridged his underground roots with mainstream sensibilities without losing either.

- From the same TCJ interview: “When the Turtles hit, that’s when the drawing stopped.... Pete and I really couldn’t find enough time — because he was handling part of the business, and I was handling part of the business...”

- Which is to say there’s only one ongoing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles title and the occasional spin-off; no need to deal with decades of continuity cross-pollinated across hundreds of titles.

- Possibly one of the reasons he sank so much money into Tundra - basically fulfilling the teenage indie dream of just giving all your creator mates money so they could do whatever they want, albeit with ruinous results. Laird, meanwhile, had a more successful run with the Xeric Foundation, which gave direct cash grants to future luminaries such as Adrian Tomine, Gene Luen Yang, Tom Scioli, and many more.

- This brings to mind Kaare Andrews’ Spider-Man: Reign, another attempt to do The Dark Knight Returns with a different comics character that didn’t turn out so well; still, while it got a lot of scorn back in 2007, it also had a kind of manic energy and some out-there storytelling which made it a lot more memorable than the genericized Last Ronin.