I was part of the Mighty Marvel Boycott, and there were at least twenty of us who put morality ahead of fanboy pleasure and brought Marvel Entertainment Inc., a subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company, to its multinational knees. (Because of us, The Avengers made $249 less at the box office.) When Marvel settled with the Kirby family in September 2014, I was finally free to watch the Avengers eat schwarma, but the bombast of the 45 minutes before that scene left a bad taste in my mouth. Guardians of the Galaxy couldn’t compete with repeat viewings of my Robert Bresson DVDs—because, of course, the only kind of stuff we discerning boycotters watched during our self-imposed exile were art films like Pickpocket and Mouchette. More recently, I enjoyed the early episodes of Nexflix’s Daredevil for its noir aesthetics and fight choreography, but its brutality keeps me from finishing the series; it’s too early to reboot the Abu Ghraib franchise, too soon for me to celebrate torturers and applaud the Chicago Police Department’s black sites. Movies like The Avengers: Age of Ultron are more innocuous; I saw Ultron a month ago, I don't remember it at all, and I'm not sure I ever need to see a Marvel movie again.

And the comics? I’ve only read a few of the comics. When social media brings me news about Marvel characters—Wolverine’s dead, Iceman’s gay, and Daredevil’s wisecracking again!—I respond as I would to rumors about a branch of the family in the Old Country: mildly interested, but I haven’t seen those folks in decades. I do feel perturbed over this year’s Marvel event, the resurrection of Secret Wars, only because my twenty-two-year-old self found the original Secret Wars the worst comic he’d ever read. (I might still agree with him, if I could bear to reread it.) If Marvel had any shame, they’d send agents to all known comic shops to buy and destroy, Mr. Arkadin-style, every copy of Secret Wars they find.

But don’t burn Hawkeye. Read and appreciated by a horde of fans before me, Hawkeye—written by Matt Fraction and often drawn by David Aja—is worth our attention. Marvel released Hawkeye #1 in October 2012, and to date 21 issues have appeared, with most of these collected into three trade paperbacks, My Life as a Weapon (2013), Little Hits (2013) and L.A. Woman (2014). Although individual issues sometimes tell self-contained stories, the series as a whole is unified by its low-key aesthetic: a text page at the beginning of these comics reads, “Clint Barton, a.k.a. Hawkeye, became the greatest sharpshooter known to man. He then joined the Avengers. This is what he does when he’s not being an Avenger.” Clint’s days off are still busy: he mentors a young superhero archer named Kate Bishop (she’s almost as much the main character as Clint), and antagonizes Eastern-European mobsters trying to chase everyone out of the New York City tenement where he lives. The clash between Hawkeye and the mobsters (nicknamed the Tracksuit Draculas) escalates to a deadly siege by the end of the Fraction-Aja run. Hawkeye #22, due July 15th, will bring this arc to a close.

Finding the right tone for Hawkeye was a trial-and-error process. In “How to Write Hawkeye,” an essay in Brian Michael Bendis’ book Words for Pictures: The Art and Business of Writing Comics and Graphic Novels (2014), Fraction notes that his original pitch for the character

ended up being published as issues 4 and 5. It’s our first two-part storyline and is very different than the issues on either side: international travel, glamorous and exotic casinos, international cabals of evil. Clint-as-Bond, where he’s in a tux more than a supersuit. Marvel said okay—remember, we just needed like nine of these—but I pulled out because it wasn’t right. When I sat down to write it, it wasn’t right, and I had to leave. I had a story, not a book, and so I stopped. (55-56)

Inspired by The Rockford Files and The Avengers (Steed and Peel), Fraction recalibrated his Hawkeye pitch to “street-level, real-world kinds of stories.” In “How to Write Hawkeye,” Fraction explains that he compensates for the quotidian nature of his Hawkeye “with a complicated structure that would reward close-reads. So yeah, there might be an issue that’s about Clint trying to buy tape [#3], but it’s going to start with a car chase, cut back two days, then cut forward again, and on and on” (56). There’s interesting storytelling here, even for readers bored by superheroes. In this essay, I discuss these complex narrative structures and techniques; what follows is an opinionated reading of the series, where I try to understand its experiments and critique its weaker moments.

An avalanche of spoilers forthcoming...

-----

The first three issues set norms against which Fraction and Aja’s later storytelling innovations take place. All three begin in media res, with Clint Barton in danger—falling out of a high window, diving into a swimming pool through a rain of machine gun fire, chased by the Tracksuit Draculas in a 1970 Dodge Challenger stunt-driven by Kate—and each of these stories opens with the same phrase: “Okay…this looks bad.” Hawkeye #1 never presents the circumstances that led up to Clint falling several stories into the roof of a parked car, but the results are multiple injuries and a six-week hospital stay. After Clint returns home to his tenement apartment, the plot follows, in normal chronological order, Clint’s first encounter with the mobsters, and his attempt to buy the building from the gang (which ends in a life-threatening brawl). There are, however, three pages that interrupt chronological storytelling, switching instead to flashforwards of Clint taking a Tracksuit’s badly wounded dog to a vet clinic. By the end of Hawkeye #1, the main plot introduces the dog as a character, catches up with the flashforwards, and reveals that the dog was hit by a car during the climatic fight. As Fraction points out, Hawkeye #1 offers mildly tricky storytelling for pop culture readers used to chronologically-challenging movies like 500 Days of Summer (2009) and The Hangover (2009).

The in media res slam-bang opening, the “Okay… this look bad” mantra, the play with chronology: these continue, usually with variation, across the Fraction-Aja run. (My favorite variation is the one that opens Hawkeye #15, where Clint accidentally drops his pants in front of Tracksuit hoods, while thinking “Okay…this looks…completely ridiculous.”) Issue #2 begins with the swimming pool dive, and repeats the “Okay” phrase no less than three times (including once on the first page and once on the last page, creating narrative bookends), but the story avoids flashbacks and flashforwards. Hawkeye #3, however, juxtaposes Clint and Kate’s present-tense car chase with flashbacks showing that the mess began because Clint slept with “Penny,” a woman later revealed to be the wife of a Tracksuit.

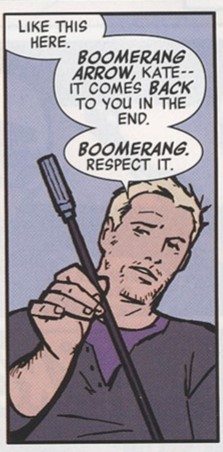

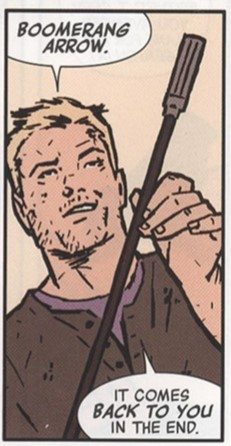

In Hawkeye, narrative strategies like the in media res opening, the flashbacks, and the flashforwards are complimented by Fraction and Aja’s use of motifs to thicken individual issues and stories. In #3, two different lists—the “nine terrible ideas” Clint has on the day the story takes place (featured in first-person captions), and a catalog of the trick arrows in Clint’s quiver (featured in inset panels with labels like “Explosive-tip Arrow”)—offer running commentaries on the dominant story. Sometimes Hawkeye’s echoes and callbacks can be very on-the-nose, as in the small panels of Clint praising his boomerang arrow that appear early and late in the story.

Fraction and Aja get more subtle with the motifs they weave into later issues of Hawkeye. I’m thinking of issue #15, titled “Fun and Games,” which is structured around the visual pattern created by overhead shots of crossword puzzles. Clint’s brother Barney works on crosswords with clues that sometimes refer to important story elements; for instance, “Five letters, comic entertainer” / “Clown” refers to a hired killer named Kazi, who ambushes Clint and Barney at the story’s conclusion. Throughout the story, Aja draws analogies between crosswords and other grids (Polaroids and Post-It Notes on a bulletin board, a map of Clint’s neighborhood), but the most dramatic comparison comes after Kazi’s attack, where Clint and Barney lie wounded against a tiled floor that looks like a crossword puzzle or giant Chess board.

Fraction and Aja get more subtle with the motifs they weave into later issues of Hawkeye. I’m thinking of issue #15, titled “Fun and Games,” which is structured around the visual pattern created by overhead shots of crossword puzzles. Clint’s brother Barney works on crosswords with clues that sometimes refer to important story elements; for instance, “Five letters, comic entertainer” / “Clown” refers to a hired killer named Kazi, who ambushes Clint and Barney at the story’s conclusion. Throughout the story, Aja draws analogies between crosswords and other grids (Polaroids and Post-It Notes on a bulletin board, a map of Clint’s neighborhood), but the most dramatic comparison comes after Kazi’s attack, where Clint and Barney lie wounded against a tiled floor that looks like a crossword puzzle or giant Chess board.

Fraction and Aja’s simultaneous attention to motifs specific to individual issues (like #15’s crossword) and strategies that cut across larger sections of Hawkeye’s run (such as the non-chronological storytelling in so many issues) really do make Hawkeye an impressive comic book. Some issues, though, are better than others.

-----

Hawkeye #4, 5 and 7 seem to me among the weakest issues of the title. After establishing his “street-level,” narratively complex Hawkeye with the first three issues, Fraction resurrects his international, glamorous “Clint-as-Bond” pitch plot, sending Clint and Kate to the made-up country of Madripoor for an adventure full of action but light on innovative storytelling. Issue #5, for instance, begins with “Okay this looks bad” and an in media res splash of Clint tied to a chair and crashing out of a skyscraper window, but the only flashback in both issues immediately follows this splash, as a single page rewinds to “A Couple Seconds Ago” to explain why Clint crashed through that window. Otherwise, the Madripoor two-parter is mostly action and laughs in the standard Mighty Marvel Manner, with the plot’s few gestures towards thematic weight (particularly the possibility that Clint might’ve assassinated a foreign terrorist) undercut by Javier Pulido’s John-Romita-Junioresque art.

More in keeping with the real-world focus of the first three issues, Hawkeye #7 is still uneven. This issue is another without David Aja’s art—over the course of the series Aja was increasingly unable to meet deadlines—and the comic is split into two stories, featuring Clint and Kate coping with Hurricane Sandy, which battered New York City and the New Jersey shore in the fall of 2012. First is Clint’s story (the first sentence of which is “Okay…this storm is really starting to look bad…”), as he accompanies his tenant and friend “Grills” to Far Rockaway, Queens, to move Grills’ misanthropic father out of his in-danger home. The clean, attractive art is by Steve Lieber, whose naturalism is close to Aja’s minimalism, and although the story feels slight, Fraction does establish a greater intimacy between Clint and Grills, a closeness that he exploits for dramatic impact two issues later when Grills is murdered.

In Hawkeye #7’s second story, Kate attends a wedding in Atlantic City, the epicenter of the storm, where the wedding party gets trapped inside the reception hotel. When the bride’s mother needs medicine, Kate ventures out into the water to find a Duane Reade, and confronts looters. This is a rough one: Jesse Hamm’s sketchy, exaggerated cartooning is a poor match for the series’ aesthetic, and Fraction’s script finishes with a corny “Jersey Rules!” climax. There are things I like about Hawkeye #7—the friendship between Clint and Grills, the Steve Lieber art, the way the issue opens with a big panel of Clint’s tenement in the rain and ends with the same image after the storm’s passing—but the issue still reads like a fill-in. I should point out, though, that Fraction graciously donated his royalties from this issue to the Red Cross and other Sandy relief efforts, so I hope it sold lots of copies.

The absence of David Aja hurts these issues. Aja is a problem-solver, an artist devoted to story: his panel-to-panel continuity is always clear (unless Fraction calls for temporal or spatial disruption), and his layouts read like architectural diagrams rather than emotional outbursts. His work has a coolness that contrasts with the kinetic ferocity of peak Kirby or the sensuousness of Craig Thompson’s line. (When I told my friend, cartoonist Ben Towle, that I was writing on Hawkeye, he said, "Aja's studied his Batman: Year One," and one of the big similarities between Mazzucchelli and Aja is a clear, neutral line.) Some consider this coolness a deficiency, but the combination of Fraction’s scripts and Aja’s clarity results in complex formalism and unexpected self-reflexivity. One example: Hawkeye #13. Throughout this issue, Aja and Fraction strike a muted, elegiac tone by sticking exclusively to a traditional nine-panel grid, including a scene at the conclusion where the cast assembles on the tenement rooftop:

As the inhabitants of Clint’s building accept Barney as one of their “family,” Clint walks to the edge of the roof and strikes a lookout position. With each panel, Aja draws the tenement further and further away, and each bright window represents lives in jeopardy that Clint assumes the responsibility to protect. But the uniformity of the windows and the black gutters between them also mirror the uniformity of Hawkeye #13’s layouts. Fraction and Aja finish off issue #13 on a note of appropriate dread, and create an unobtrusive metaphor for their own creative method. I don’t see formalism like this in Fraction’s collaborations with other Hawkeye artists, or in any other mainstream comics.

-----

Aja draws issue #6, which begins Fraction and Aja’s most experimental phase on the title. Called “Six Nights in the Life Of…”—to bleed into the title Hawkeye—the plot covers six nights in Clint’s life during the Christmas season, from Thursday, December 13th to Wednesday, December 19th: (No scenes are presented from the evening of Sunday, December 16.) Here are the events of those six nights:

Thursday, December 13: Hawkeye, Spider-Man and Wolverine battle Agents of A.I.M.; although the heroes win, Hawkeye is hurt (“I think my concussions are getting concussions”).

Friday, December 14: Hawkeye attends a rooftop party with the tenants of his building. The Tracksuit Draculas lure Clint out of the building, and overwhelm him with dozens of henchmen (“Okay… this looks unjoyous”). Clint is hooded, abducted, and driven to a warehouse full of Tracksuits.

Saturday, December 15: The abduction continues from the previous evening. The capo of the Tracksuit mob, an old man who sucks nitrous from a plastic mask like Dennis Hopper in Blue Velvet (1986), tells Clint to leave the building or else (“You gone or we keeling everybody in your building, Bro”). Clint is returned to his building, where he decides to follow the capo’s advice. Before he leaves, he asks a bike-messenger in his building to deliver his bow to Kate. Within the hour, Kate arrives at Clint’s apartment and chides him for even thinking about running away (“This running away thing? It’s everything about you that sucks”).

Sunday, December 16: Clint spends the rest of Saturday pondering whether he should stay or go. As the clock strikes midnight and the calendar changes to Sunday, he walks outside the building with his bow and arrow, striking a defensive posture that indicates to the Tracksuits that he will not be leaving. (The next scene jumps forward almost two days, to Monday night.)

Monday, December 17: As Clint moves into his apartment “like a grown-ass man,” one of his tenants, Simone, complains that the building’s satellite dish isn’t working. She’s worried that her youngest child will miss his favorite Christmas TV special. When Clint asks the Super to fix it, he refuses, noting that he deals with “equipment failure” and the dish was actually damaged by a stray arrow Clint fired during the Saturday night Tracksuit massacre.

Tuesday, December 18: Tony Stark comes to Clint’s apartment to help set up his stereo.

Wednesday, December 19: Clint has settled into his apartment; we see him hanging his bow above his couch. Simone drops off her two kids for Clint to babysit. When Simone asks, “Are you sure this is okay? Do you need to be somewhere?” Clint replies, “Nope. I’m not going anywhere.”

The above outline is (hopefully) clear, but the plot scrambles up these story events, presently them wildly out of order. The issue begins with Clint and Tony working on the stereo, whips back five days to the fight with A.I.M., briefly returns to Clint and Tony, backtracks for a single page to December 17 and Clint’s initial attempts to settle into his apartment, shifts into a multiple-page chronicle of Clint’s confrontation with the Tracksuits, etc. (To construct the above outline, I copied every page in the comic and shuffled them into chronological order; the two versions of Hawkeye #6 are very different from each other.) Hawkeye #6, then, takes narrative fragmentation much further than the “cut back, then cut forward again” structure of the earlier issues, and this fragmentation creates transitions between pages and scenes that strike thematic and narrative notes. On page 16, for instance, Clint struggles to operate his TV remote, and then someone knocks on the door:

There are two different people at Clint’s door. If a reader continues directly onto page 17 (and thus flashes back to December 15), it’s Kate, who returns Clint’s bow and calls him on his cowardice.

If that same reader jumps across pages to assemble a chronological story, s/he will leap to page 21, the final page of the comic, and see Simone and her kids in the doorway.

There’s a thematic cause-effect channel created among these three pages: if Kate hadn’t reignited Clint’s conscience and sense of responsibility on the night of December 15, Clint would not be babysitting Simone’s kids on December 19.

The sequence from pages 15 to 18 also turns Clint’s bow into an important symbol. On page 15, Clint returns home, bruised and scared, and in panel 6 we see the bow hanging over his couch—but then he takes it down and sends it to Kate. Then on page 16 (but four days later), the bow is again in its place of prominence above the couch, and we wonder how it has returned to his apartment. Then we see (on pages 17 and 18, December 15) Kate immediately bring the bow back to Clint, but he only regains his status as a hero when, on Sunday December 16, he picks up the bow again to protect his building from the Tracksuits. Finally, back to December 19 (page 16): Clint proudly displays the bow again. The achronological storytelling clumps these activities with the bow into four pages, making its symbolism clearer than if the plot had been told in order. In its combination of a (relatively) realistic story with mixmaster plotting, Hawkeye #6 may be the best, and most representative, single issue of the title.

-----

Hawkeye #8 and 9 continue the narrative innovation, with an emphasis on repeating scenes. Issue #8, “My Bad Penny,” reintroduces the woman affiliated with the Tracksuit Draculas that Clint slept with in #3. Now Penny persuades Clint to join her in raiding a Tracksuit strip-joint to steal a small safe (the contents of which remain a MacGuffin to be revealed in the as-yet-unreleased #22). This story is interrupted by five splashes presenting covers for made-up romance comic books with titles like A Girl Like You and Love Fugitive. These covers are drawn by Annie Wu, while the main story art is by Aja.

Although these covers are used ironically (the Clint/Penny booty call isn’t exactly a chivalric romance), it’s not their inclusion that I find groundbreaking about Hawkeye #8’s plot. Rather, a brief scene on pages 3-4 of #8 prefigures a repetition-with-variation strategy that Fraction uses frequently in later Hawkeyes. “My Bad Penny” opens with one of the faux comic book covers (Doomed Love), followed by a page-long scene where Penny shoots a member of the Tracksuit gang. Then the title page for “My Bad Penny” jumps forward to Penny arriving at Avengers Mansion and asking for Clint’s help. This situation “looks bad” for Clint because he’s playing Blind Man’s Bluff Poker with an old girlfriend (Natasha, the Black Widow), his ex-wife (Bobbi, Mockingbird) and his current girlfriend (Jessica, Spider-Woman), and this is how Jessica discovers that Clint has cheated on her. Clint is aware of how he’s hurt Jessica, but he still allows himself to be manipulated by Penny. In a later scene, while fighting with Tracksuits at the strip-joint, Clint diagnoses himself: “There’s gotta be a better way to tell my girlfriend…the thought of a serious relationship makes me nervous.”

This situation “looks bad” for Clint because he’s playing Blind Man’s Bluff Poker with an old girlfriend (Natasha, the Black Widow), his ex-wife (Bobbi, Mockingbird) and his current girlfriend (Jessica, Spider-Woman), and this is how Jessica discovers that Clint has cheated on her. Clint is aware of how he’s hurt Jessica, but he still allows himself to be manipulated by Penny. In a later scene, while fighting with Tracksuits at the strip-joint, Clint diagnoses himself: “There’s gotta be a better way to tell my girlfriend…the thought of a serious relationship makes me nervous.”

Hawkeye #9 (“Girls”) opens with a repeated-with-variation version of this same. The first page of #9 shows Jarvis, the Avenger’s butler, answering the door. Penny springs inside and kisses Clint, leading into a page that reuses three panels from the issue #8 page above (although Penny’s word balloons in panels 1 and 2 are oddly swapped from the issue #8 version): Hawkeye #8 presents more of the aftermath of the kiss—Jessica asks “Why did she kiss you?” while Natasha points out that they can’t harbor a possible criminal in Avengers Mansion—while #9 cuts directly from its title page to events beyond what we saw in the previous issue. But why repeat any portion of the scene at all? For emphasis. Through repetition, Fraction and Aja emphasize how Clint’s behavior alienates the people closest to him. The narrative structure of #6 reaffirmed Clint’s heroic status, but the repetition of the Clint / Penny kiss underlines how Clint backslides into intimacy fears and irrational behavior. Near the end of #8, after his strip-club attack, Clint spends the night in jail and worries about losing his Avengers membership. In #9, which ironically takes place on Valentine’s Day, he’s slapped twice by his ex-girlfriend, he signs the final divorce papers for his ex-wife, and he’s so depressed that he can barely speak to his best friend Kate (“Help yourself to whatever. Or go home. I don’t care.”). In the final scene of #9, Kazi murders Grills. Shit gets bad, Clint handles it badly, and he and Fraction repeat the mistakes.

Hawkeye #8 presents more of the aftermath of the kiss—Jessica asks “Why did she kiss you?” while Natasha points out that they can’t harbor a possible criminal in Avengers Mansion—while #9 cuts directly from its title page to events beyond what we saw in the previous issue. But why repeat any portion of the scene at all? For emphasis. Through repetition, Fraction and Aja emphasize how Clint’s behavior alienates the people closest to him. The narrative structure of #6 reaffirmed Clint’s heroic status, but the repetition of the Clint / Penny kiss underlines how Clint backslides into intimacy fears and irrational behavior. Near the end of #8, after his strip-club attack, Clint spends the night in jail and worries about losing his Avengers membership. In #9, which ironically takes place on Valentine’s Day, he’s slapped twice by his ex-girlfriend, he signs the final divorce papers for his ex-wife, and he’s so depressed that he can barely speak to his best friend Kate (“Help yourself to whatever. Or go home. I don’t care.”). In the final scene of #9, Kazi murders Grills. Shit gets bad, Clint handles it badly, and he and Fraction repeat the mistakes.

Also continuing in issue #9 is out-of-sequence storytelling. Most of “Girls” follows how the women in Clint’s life react to his downward spiral: Natasha trails and confronts Penny (and learns of a supervillain plot on Clint’s life); Bobbi finalizes the divorce; and Jessica comes to Clint’s apartment to scold him for sabotaging every one of his romantic relationships “the second it got difficult.” As in issue #6, the page-to-page continuity of “Girls” is not chronological. Fraction again prompts us to reassemble pages out of publication order, to realize that the night after Clint is in jail, both Jessica and Kate visit Clint’s apartment before Bobbi. Fraction’s rearrangement of the pieces, however, puts Clint’s encounters with his three exes before his debriefing with Kate, and it feels right for Kate to go last. The early issues of Hawkeye are about the growth of the Clint / Kate friendship, and the slow collapse of this friendship is the climax to Clint’s increasing estrangement from everyone who cares for him.

-----

I’m violating chronology myself, and skipping over Hawkeye #11 until the next section of this essay, because issues #10 and #12 have numerous connections. Both issues are drawn by Francesco Francavilla in a style that’s rougher and pulpier than Aja’s coolness, and Francavilla also colors both issues in an almost garish palette of yellows, oranges, purples and reds. I like Francavilla on Hawkeye much more than Pulido, partially because of this vibrant coloring, and partially because Fraction's scripts are more tightly bound into the experimental storytelling of Hawkeye’s middle period and the trajectory of the series as a whole. (More on this soon.)

Most importantly, Hawkeye #10 and #12 are origin stories. Issue #10 juxtaposes a flirty encounter between Kate and Kazi at a New York party with flashbacks outlining Kazi’s childhood and the tragedies (growing up in a war zone, the death of his parents and brother) that led to his career as an assassin. Issue #12 likewise combines present-day events—Clint’s reunion with down-on-his-luck Barney—with flashbacks to Clint’s childhood in Iowa and the abuse both brothers took from their father. Fraction and Francavilla create a “one bad day” parallelism between Kazi and Clint, right down to splintered layouts for each that represent trauma and the consequences of unbearable events. In #10, jagged splash pages reveal Kazi’s mental state as he becomes a sociopath. In two of these splashes, published consecutively in the comic, Kazi assumes the identity of the “Clown” and goes on a murderous rampage during his “first real day of work”:

In the flashbacks in Hawkeye #12, the death of Clint and Barney's parents in a car accident is also represented as a splintered splash page:

In the flashbacks in Hawkeye #12, the death of Clint and Barney's parents in a car accident is also represented as a splintered splash page:

The car crash as primal trauma haunts Hawkeye and Hawkeye. In issue #3, Penny is abducted by the Tracksuits, and Kate and Clint save her by ramming into the getaway car. Immediately after the collision, Kate teases Clint with a joke that gains significance in retrospect:

The car crash as primal trauma haunts Hawkeye and Hawkeye. In issue #3, Penny is abducted by the Tracksuits, and Kate and Clint save her by ramming into the getaway car. Immediately after the collision, Kate teases Clint with a joke that gains significance in retrospect:

The car crash connects to the love life: Clint, still grappling with the effects of childhood abuse, can't figure out why he sabotages his friendships and romances. In a previously reproduced panel from Hawkeye #6, Clint tells himself (in an interior monologue) that he needs to face the challenges of his “car-crash life,” the pernicious influences his parents’ flaws and tragic deaths continue to have over his adult behavior. Kazi and Clint are both trauma survivors, but while Kazi fully succumbs to nihilism and madness, Clint struggles—sometimes successfully, sometimes not—to be a better man and hero.

The car crash connects to the love life: Clint, still grappling with the effects of childhood abuse, can't figure out why he sabotages his friendships and romances. In a previously reproduced panel from Hawkeye #6, Clint tells himself (in an interior monologue) that he needs to face the challenges of his “car-crash life,” the pernicious influences his parents’ flaws and tragic deaths continue to have over his adult behavior. Kazi and Clint are both trauma survivors, but while Kazi fully succumbs to nihilism and madness, Clint struggles—sometimes successfully, sometimes not—to be a better man and hero.

-----

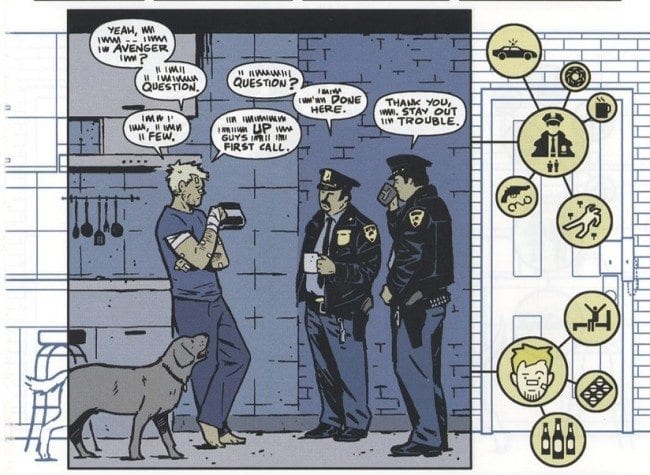

When Hawkeye #11 came out in July 2013, critical response ran from raves (Rachel Edidin wrote that “it’s not just that it’s the best comic of the year…Hawkeye #11 might be the best comic ever”) to the Comic Books are Burning in Hell pushback against the raves (the comparison between Aja's diagrammatic art and the blandness of an airplane instruction card). Both sides of the debate, however, emphasized how #11 tells its story. Its central character is Lucky, the dog Clint adopts in the first issue of Hawkeye, as he wanders around Clint’s tenement, discovers Grills’ corpse, and sniffs out Kazi and a group of Tracksuit Dracula inside the building. Fraction and Aja use diagrams to represent Lucky’s non-human and point-of-view, as in this scene where Barney is introduced as a character:

The diagrams are Lucky’s perception of the scene. One of the Tracksuit Draculas calls the dog “Arrow”—Lucky’s previous name, when he was a pet of the gang—and the pictograms of the gang members are Lucky’s memories of how those thugs mistreated him. Like Clint, like Kazi, Lucky is damaged goods, a wounded mongrel. Lucky’s understanding of Barney is a question mark, however, because Barney is both the same and different from Clint; the wavy top line of the equals sign looks like the emanata for “smell” in cartoon iconography, and Lucky smells but doesn’t understand that Clint and Barney are family. All the diagrams in Hawkeye #11 cleverly transmit story information, though some criticized Aja’s diagrams as too close to Chris Ware’s style.

But nobody talks about how deeply #11 is entangled in the ongoing Hawkeye story. In the previous example, Lucky figures out—and communicates via diagram—that Barney is Clint’s brother, but it takes another issue (#12) until their connection is concretely established through dialogue. The artistic strategy throughout Hawkeye #11 is to present significant scenes through Lucky’s non-human focalization, which blurs words and leaves our own comprehension of these scenes incomplete. One example: in Hawkeye #10, Kate returns from the party where she flirted with Kazi, and falls into an argument with a depressed and angry Clint.

In #11, we get Aja’s take on this scene, as we discover that Lucky heard and saw the argument. This example isn’t too befuddling for readers, because if we read the issues in order, we get a complete version of Kate and Clint’s disagreement before we read Lucky's indecipherable-squiggles-in-the-word-balloons perception. Across the span of Hawkeye #11-13 and Hawkeye Annual #1, however, the reverse is much more common: Lucky's fractured, incomplete take of a scene appears first, and is then repeated in a complete form in subsequent issues. Here are some examples:

In #11, we get Aja’s take on this scene, as we discover that Lucky heard and saw the argument. This example isn’t too befuddling for readers, because if we read the issues in order, we get a complete version of Kate and Clint’s disagreement before we read Lucky's indecipherable-squiggles-in-the-word-balloons perception. Across the span of Hawkeye #11-13 and Hawkeye Annual #1, however, the reverse is much more common: Lucky's fractured, incomplete take of a scene appears first, and is then repeated in a complete form in subsequent issues. Here are some examples:

--In #11, when Barney is introduced, he is being beaten by Tracksuits, but #12's re-run reveals that Barney hired himself out as a punching bag for five dollars, dramatizing how degraded he’d become before he contacted his brother. (First sequence drawn by Aja; second by Francesco Francavilla.)

--After Grills’ body is discovered, the police interview everyone in the tenement, including Clint. In the first version (#11), the interview is impossible to follow, but issue #13 provides a user-friendly recap:

--One of Lucky’s diagrams in issue #11 tells us that Clint and Kate are going to Grills’ funeral—there is a pictogram of a hearse--but the fuller account of the dialogue in #13 emphasizes how impatient Kate has become with Clint’s self-absorption:

--Finally, the tensions escalate between them to the point where Kate leaves Clint and New York, to drive out to California and be an independent Hawkeye. Her farewell is repeated no less than three times in the series, first as perceived by Lucky in #11:

A month after the release of Hawkeye #11 (September 2013), Hawkeye Annual #1 begins with Kate’s departure (weird silhouette art by Javier Pulido):

And because chronological scrambling is the M.O. of these mid-series Hawkeye issues, #13 reveals that Clint and Barney have reunited before Kate leaves—in fact, Barney is using Clint’s upstairs bathroom as Kate and Lucky make their exit.

All these half-portrayed scenes are repeated and fleshed out as the larger Hawkeye narrative unfolds, and this delaying tactic is an uncommon, but not unique, technique in literature and comics. At the beginning of the chapter of Ulysses (1922) titled “The Sirens,” James Joyce lists an overture of non-sequiturs (“Bronze by gold heard the hoofirons, steelyrining imperthnthnthnthnthn. / Chips, picking chips off rocky thumbnail, chips. Horrid! And gold flushed more.”) that are only explained over the course of “The Sirens." A seemingly nonsensical phrase like “Then, not till then. My eppripfftaph. Be prfwritt” snaps into focus as Leopold Bloom wanders in a graveyard, reading tombstones while passing gas. So too the first page of “A State of Darkness,” chapter two of Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell (1999), where a grid of nine black panels displays phrases—“What is the fourth dimension?” “Less than a thimble-full of iodine divides the intellectual from the imbecile”—that make sense only in the context of the chapter to come. Hawkeye #11 functions in much the same way as the beginnings of “The Sirens” and “A State of Darkness”: as a collection of hints that create cliffhangers, that make readers wait for a clearer understanding of each of these scenes.

Fraction and Aja, then, have again complicated the “cut back two days, then cut forward again” structures of the early issues: the multiple instances of repetition-with-variation across the #10-#13 issue span is a kind of Hawkeye #6 writ large, offering multiple pathways for reading and re-reading. This is perhaps where the original issue-by-issue release of Hawkeye was a challenge, since keeping events and chronology in order over several months is harder than flipping pages in an all-in-one volume. (Once Hawkeye #22 comes out, Marvel is scheduled to publish a Hawkeye Omnibus that collects all the issues—including the Annual and a Clint-Kate story from Young Avengers Present #6—into a single, massive book.)

The significance of this repetition-with-variation storytelling goes beyond the Rubik-like pleasures of “solving” plot order and character location. Earlier, I argued that the repetition in issues #8 and #9 emphasizes Clint’s poor treatment of Jessica and a general backsliding from his best self. The repetition across #10 through #13 likewise shows characters in dire straits: Clint is drinking too much (ominous, given his father’s struggles with alcoholism), Clint and Kate’s partnership dissolves, and Barney is a masochistic bum. These repeated events are more typical of a naturalistic soap opera than the apocalyptic stakes of most superhero narratives. Clint’s personal struggles—and some of Barney’s too—are the emotional and dramatic center of the narrative, repeated just in case you missed their importance, and the superhero stuff is almost superfluous.

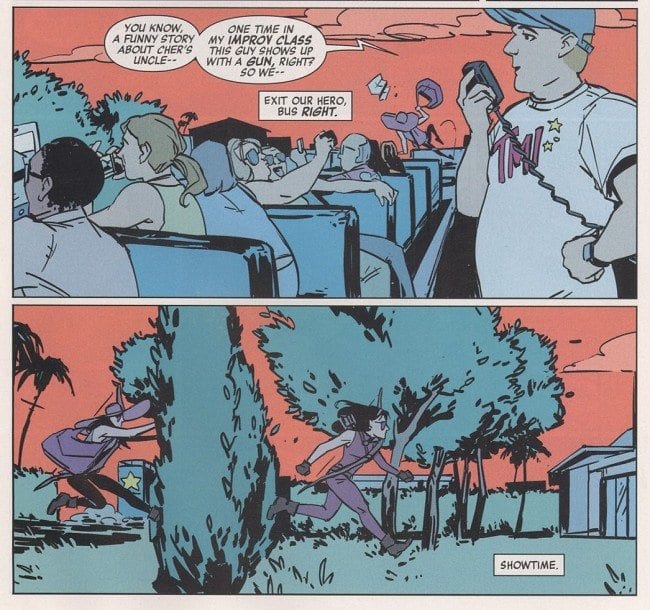

Issue #13 opens with Clint composing a letter of apology to Jessica (which explains Clint’s reference to calling Bobbi with “a spelling question” in one of the #11/13 examples above), when he is interrupted by a page from the Avengers, summoning him on a mission. (Giving Clint a pager underlines his sad-sack status and lack of tech-savvy too much, maybe, though it reminds me of a great line about pagers from the first season of 30 Rock: “I’m expecting a call…from 1983.”) On the final tier of the first story page—a recto page—Clint gets ready for battle.

And then, on the verso page turn, the next two tiers:

The battle is omitted. We never see the bad guy. Instead, the importance of the scene lies in the final two panels above, where there’s a frosty tension between Clint and Jessica, a tension that continues as the heroes leave the wreckage and report to a hospital facility. (The scene only breaks when Clint receives news of Grills’ death.) It’s tempting to read this scene as an action plan for Hawkeye as a whole: Fraction and Aja pare away typical superhero action to zero in on what Clint does “when he’s not being an Avenger,” which allows the relationships between characters, and Clint’s own descent into isolation, to generate the real drama of the series. And Fraction encourages us to pay attention to those relationships by repeating scenes and embedding a human heart within his puzzle structures.

-----

After the narrative tumult of Hawkeye #8-13, the strip settles down into a two-pronged structure, with even-numbered issues illustrated by Annie Wu that chart Kate Bishop’s adventures as a superhero/P.I. in Los Angeles, and odd-numbered issues by Aja that focus on Clint’s continued struggles with the Tracksuit Draculas. (Dividing the plotlines is a logical consequence of the emotional tension that Fraction develops between Clint and Kate, but it’s also a way to shift Aja’s deadline from monthly to bimonthly—although Aja still misses several of his bimonthly Hawkeye deadlines too.) The Kate plot begins in Hawkeye Annual #1 (a visual example of which is the double-page spread replaying Clint and Kate’s kitchen farewell.) The Annual is my least favorite Hawkeye comic, mostly due to Javier Pulido’s art. Pulido drew Hawkeye #4-5—the jet-setting Madripoor adventure—in a clear, competent Marvel house style, but in the Annual he draws most of the human figures as silhouettes rather than detailed characters. Here’s an example of a page clotted with silhouettes:

Not exactly Kara Walker. Visually, the entire Annual is like this, a parade of shadows moving through thinly delineated backgrounds: Pulido doesn’t even try to create a realistic fictional space, and Hawkeye’s first evocation of California comes off as artificial and two-dimensional (which might be appropriate for a Baudrillardian reading of L.A., but is not at all in sync with the series' aesthetic).

In the page above, the pony-tailed silhouette in purple-and-white checks is Kate. The woman in the black dress (“Whitney Frost”) is a mask-less Madame Masque, out for revenge for humiliations suffered in issues #4-5. The “Kate in L.A.” arc spans the Annual and issues #14, 16, 18 and 20, is collected in the L.A. Woman trade, and is organized around skirmishes between Kate and Masque. (Some of these skirmishes mirror previous elements in Hawkeye; just as Clint perpetually crosses paths with the Tracksuits, so Kate frequently battles a cadre of zombie bellhops.) Masque tries to ruin Kate’s life by framing her for murder and burning down her trailer home, while Kate doggedly investigates Masque’s monstrous scheme to provide the aged mega-rich with young bodies. Scenes charting this overarching conflict, however, alternate with smaller stories that begin and conclude in a single issue, such as #16’s roman à clef version of Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys, and the (un)making of Smile. These done-in-one tales are OK, but rendered almost irrelevant by their digression from both the key Kate and Clint plots—readers know that “Will Bryson” and the “Bryson Brothers” aren’t Hawkeye’s main event.

I like Annie Wu’s art on the Kate stories. In some ways, Wu’s art is the anti-Aja. Aja’s art is all reserve, poise and simplicity, while Wu’s line is more jagged and sketchy, and her layouts are cramped and idiosyncratic. Wu realizes that moving Kate to California is a new direction, and thus wisely sets up a visual approach distinct from Aja’s. She is helped by Matt Hollingworth’s coloring, which gives Kate a blue-green palette more expressionistic than the muted purples of Clint’s adventures. Below is a sample from #16. (Interestingly, issue #20 returns to the Clint hues, as Kate decides to return to New York.)

Despite my appreciation for Wu and Hollingworth’s work, I still have two problems with the Kate issues. First, Kate is written as a bouncy, flighty character, to the point where Pulido adorns her thought balloons throughout the Annual with a little kawaii Hawkeye. Given that the issues preceding the Kate-Clint split are dominated by Clint’s increasing depression—and given that many of the Amazon comments on the collection of these issues (Little Hits) complain about said depression—I wonder if Fraction wrote Kate’s stories to be a sunnier counterpart to Clint’s black hole. Nevertheless, there’s an odd dissonance between Kate’s relentless optimism and the horrors she sees and uncovers, especially Masque’s body-harvesting operation. More painfully: in the Kate issues, the narrative complexity of #8-13 is gone. Flashbacks are mostly used as exposition dumps, as in scenes where potential clients tell Kate about their troubles, or where a Long Goodbye-era Elliott Gould doppelgänger exposes the contours of Masque’s mad plan. Maybe presenting Kate’s stint in L.A. as a series of linear, conventional narratives was another way Fraction and Wu sought to provide an alternative to earlier Hawkeye issues, but I miss the cognitive demands of the more experimental Clint stories.

-----

All that’s left, then, are the non-Wu issues of the bifurcated late Hawkeye: #15, 17, 19, and 21. I say “non-Wu” instead of “Aja” because one of these, #17, is a fill-in issue drawn almost completely by regular series letterer Chris Eliopoulos in his cartoony, Bill Wattersonesque style. The issue is a flashback to the last page of Hawkeye #6, where Clint agrees to watch a Christmas TV special with Simone’s kids. In #17 we see the show, “The MBC Wintertime Winter Friends Winter Fun Special,” in its entirety. The “Winter Friends” are a team of animated, holiday-themed animal superheroes, but the true hero is a powerless dog named Steve who pals around with the Winter Friends and is himself shadowed by a little puppy named Lil and a big “adventure brudder” named Herman. These characters are blatant analogues for Hawkeye’s human cast (Steve is Clint, Lil is Kate, Herman is Barney, the Winter Friends are the Avengers)—and Fraction has the animated animals behave in ways consistent with his human characters, with Steve repeatedly yelling “I can do it all by myself!” and pushing away those who love him. Cute enough, but utterly unnecessary. In an August 2014 review of Hawkeye #19 at the AV Club, Oliver Sava noted that “Hawkeye has lost a lot of momentum”: “Splitting focus between two slowly moving storylines while taking months between issues severely diminished the book’s forward motion over the last year.” Fill-in issues don’t keep that ball rolling either.

I discussed issue #15 at the beginning of this essay (specifically, its use of crossword puzzle grids), but another noteworthy element of this issue is how decisively it switches into the series’ endgame. Up to this point, Fraction refused to reveal why the Tracksuits want to drive the tenants out of Clint’s building, but as we discover in #15, the Tracksuits and Kazi work for a quasi-legal consortium of real estate developers who want to flatten Clint’s tenement and make room for Manhattan’s new “luxury shopping destination.” (It’s interesting how the Netflix Daredevil show borrows this theme of corruption through gentrification—is Marvel nostalgic for the Deuce, despite Disney’s role in cleaning up New York City?) I found this real estate plot less like Big Numbers than the moment in a stage melodrama where a mustache-twirling capitalist evicts the sad, beautiful widow. Maybe the experimental second act of Hawkeye led me to hope for a more original motivation, or maybe, as Borges famously reminds us, “the solution of a mystery is always less impressive than the mystery itself. Mystery has something of the supernatural about it, and even of the divine; its solution, however, is always tainted by sleight of hand.”

Fraction still practices pretty good sleight of hand with narrative details, though: a sneaky moment in issue #15’s revelations links to the Kate-in-L.A. arc. Throughout her stay on the West Coast, Kate struggles with her relationship with her father, an emotionally distant billionaire with a trophy wife only three years older than Kate. (In Hawkeye #20, Kate is shocked to discover that her father is on Madame Masque’s customer list for a youthful body.) Both Kate and Clint have daddy issues, although Kate is less damaged by them; at the end of Hawkeye #20, she tells her father that they’ll soon “have words” about his involvement with supervillains like Masque. Kate refuses to slip into a depressive funk like Clint does in painful situations, though even she might be overwhelmed if she knew that her dad also attended the corrupt developers’ meeting with Kazi and the Tracksuits in issue #15.

This tiny "M. Bishop" word balloon is one of those graceful, second-reading Easter eggs that Fraction expresses fondness for in his “How to Write Hawkeye” essay. Details like this keep me reading Hawkeye even when the series isn’t at its narrative-scrambling best.

-----

I have relatively little to say about the final two Clint stories (so far) in the series, Hawkeye #19 and #21. At the end of #15, Kazi jams arrows into Clint’s ears, and #19 charts Clint’s depression over losing his hearing. Hawkeye as a character has a history of deafness, so much of the plot is told through Aja-designed diagrams of American Sign Language, as Barney (who also survives Kazi’s attack, but is now in a wheelchair) tries to rouse Clint out of his despair. In summer 2014, Hawkeye #19 got considerable media attention for telling its tale through ASL—and for, in the words of New York Times writer George Gene Gustines, providing “no key to interpreting” the signs. “’If nothing else, it’s an opportunity for hearing people to get a taste of what it might be like to be deaf,’ Mr. Fraction said.” Hard of hearing advocates were glad to have a hero and a story to call their own, but I’m more interested in how #19 is a callback to Hawkeye #11: both issues are filtered through the perceptions of characters who miss significant story information, both use odd word balloons (either Lucky’s squiggly ones, or blank ones to signify Clint’s deafness) to signify this absence of information, and both are key to Clint’s development as a person. In Hawkeye #11, Clint is alone; in Hawkeye #19, Clint learns the value of community.

This lesson is inexorably connected to Clint’s childhood trauma. The story open with a flashback on the first page, as young Clint stares at his father’s hands, remembering his father’s slaps and punches. (Perhaps his father boxed his ears, causing Clint's deafness.)

Following this page, issue #19 unfolds around two formal principles. First, much of the story alternates between flashbacks featuring the Barton kids—as Clint threatens to sinks into a depression over his father’s abuse, until Barney beats sense into him—and the present day, as Clint is overwhelmed by his new ear injuries and the ruthlessness of Kazi and the Tracksuits. As in the past, Barney uses violence to jolt Clint out of his passivity (“HIT THEM UNTIL THEY STOP”), while relentlessly symmetrical layouts emphasize these parallels between the Barton boys and Barton men, yet another instance of repetition in the Fraction/Aja Hawkeye.

The other unifying formal element is hands. The story begins with father Barton's hands, and segues into a plot where Clint is tempted to stop using his own hands to communicate with ASL. Barney, however, continues to sign, and he also therapeutically pummels Clint back to his emotions. (Given the environment the brothers grew up in, it’s not surprising that they talk best with their fists.) Hawkeye #19 ends with Clint deciding to set his life straight. He apologizes to Jessica for his cheating, he and Barney trash the Tracksuit strip-joint, and most importantly, he asks the building tenants for help in combating the gang, who convey their support through upraised fists:

And that’s it. Clint will be a hero, despite his flaws, which makes issue #20 a bit perfunctory, heavy on plot rather than emotional transformation. The issue’s title is “Rio Bravo”—after the 1959 Howard Hawks western featuring four gunslingers versus a brutal rancher’s gang—and escalating action is the main event: Penny returns to complicate Clint’s life, the Tracksuits raid the building, the tenants defend their turf with siege tactics, and Aja choreographs brutal, ink-stained fight scenes. Hawkeye #22’s title is “El Dorado,” the name of a 1966 Hawks film that is essentially a remake of Rio Bravo, so presumably the siege will continue until all plot threads are tied up.

-----

What conclusions have we reached about Hawkeye? I'll reiterate that I find much of Hawkeye enjoyable and aesthetically accomplished; every Fraction/Aja issue is worthwhile, and I appreciate how Fraction braids motifs throughout individual stories and the series as a whole. Immediately before writing this paragraph, I flipped through a few random Hawkeye floppies, just to make sure I didn't miss an image or a caption that should be included in this essay, and I stumbled across the following bit of dialogue from Kate and Kazi's party conversation in #10:

Kate's description of Clint as a "human car-crash" anticipates Clint's origin story--which would also be drawn by Francesco Francavilla, albeit two issues later. Further, the notion of watching Clint make mistakes "again and again" is an elegant, one-sentence summary of the repeat-with-variation-and elaboration storytelling technique Fraction brings to issues #8-13. I love that I can dip into a typical issue of Hawkeye and find a tier of panels that vibrates not only with the frisson of scene-specific character interaction, but with connections to a larger network of motifs and themes. I don't live in a town with a comic shop, but I'll drive an hour on July 15th to buy a copy of Hawkeye #22.

Even so, perhaps Hawkeye's permanent legacy will be how Fraction and Aja pushed the idea of the regularly published "mainstream" comic book past its breaking point. Fraction, Aja and Marvel kept up the fantasy of a monthly title for too long, and I dream of a better world where Hawkeye wasn't plagued by fill-ins, artistic inconsistencies, and false promises of clockwork production. (Marvel should've hired Fraction and Aja to do a single, 48-page Hawkeye graphic novel every year, and no more.) Meanwhile, Hawkeye #22 will be, for the time being, Fraction's last Marvel book. Despite Marvel's efforts to keep him happy (like the publication of Casanova through Icon, Marvel's creator-owned imprint), Fraction has defected to Image, where he gets full ownership over all his writing, bigger royalties, and the freedom to co-create blockbusters like Sex Criminals and smaller, odder books like Satellite Sam (which reads like a Howard Chaykin fanfic fortuitously drawn by Chaykin himself) and Ody-C (which would be a dynamite serial for late-'70s Heavy Metal). As I return to ignoring the Marvel movies and most of what Marvel publishes, I hope Hawkeye is just a warm-up for stranger and greater art from Fraction and Aja.

-----

In spring 2015, I taught a sophomore Honors seminar in comics and graphic novels at Appalachian State University. As part of this class, I assigned Hawkeye as a serial text, with the students reading and talking about an issue or two each week. I'm sure that some of the observations in my essay came up during our class discussions, although weeks later it's impossible for me to trace specific ideas to individuals. I'm grateful to all my Honors students for joining in the discussion. The students in that class were Ben Baker, Marit Barber, Miranda Broussard, Emily Brown, Allie Cairelli, Dylan Crowe, Zach Durham, Angela Gazzillo, Nick Gilliam, Katie Howell, Lauren Kennedy, Austin King, Erin Muir, Jabari Myles, Sara Mylin, Zach Pruitt, Jared Stratton, and Rachel Tapia. Thanks to all.