In this excerpt from Bill Schelly's forthcoming biography Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America, the author chronicles the lifespan of the magazine Humbug. Rebounding from the abrupt cancellation of Trump (the magazine he had left Mad to produce) after only two issues, Kurtzman rallied an all-star cast of cartoonists for their next endeavor.

*1976 Kurtzman photograph courtesy of E.B. Boatner.

HAVING EXPERIENCED magazine interruptus, Kurtzman and his collaborators on Trump gathered in the brownstone to commiserate. The termination of the magazine had come with no warning. The others wanted to hear the details of Kurtzman’s conversation with Hefner. The news was still sinking in. “After we finished with Trump, we all sat around . . . and we were very unhappy that we were about to break up,” Kurtzman recalled. “And Arnold Roth, who is a dear, sweet fellow . . . was the only one who came up with an optimistic attitude.”1 He also came up with a large bottle of Scotch.

As they passed around the bottle, the mood lightened. They knew they could produce a terrific magazine if only they had a fair shot at it. They were proud of Trump and confident it would have done well. (This was before Kurtzman had the actual sales figures in hand.) Given the talent in the room—each of Kurtzman’s crew was destined to have a successful career—how could they fail, if only a publisher had the good sense to back them solidly? If Mad magazine became a publishing phenomenon, there was no good reason why they couldn’t produce a magazine that would sell as well or better.

“Quality will sell” was the refrain, but after getting burned by Hefner, seeking another publisher met with little enthusiasm. One can imagine a still-resilient Kurtzman saying, “All we need to do is get a magazine on the stands next to Mad, and we could all make a fortune.” As the supply of Scotch dwindled, someone said: “Let’s publish it ourselves!”

Outrageous as it sounded, publishing their own magazine would have many benefits. The group of six—Kurtzman, Elder, Davis, Jaffee, Roth and Chester—had gotten along well in their nine months together. They would have creative control, own the rights to their own work in the magazine and split all the profits. That meant they would benefit if the material was reprinted, possibly in the paperback format that was doing so well for Mad. They would also be able to keep their own original art. (Gaines had never returned the original pages.)

A publishing cooperative, with each participant owning part of the enterprise, had never been tried in comics. Some creators had owned their own companies, like Simon and Kirby with their short-lived Mainline Comics, but the writers and artists who worked for them received none of the benefits of ownership. With the formation of Humbug Publishing Co., Inc., the workers were rising up to take group ownership of an enterprise. It was agreed that the “six musketeers” would create the magazine and split the profits equally, even though the setup differed from being a purely cooperative effort. The individual members wouldn’t simply “do their own thing.” The operation was predicated on Harvey Kurtzman being the editor and guiding force. The others wouldn’t have entertained the idea except for their confidence in their charismatic leader’s talent and vision. (Kurtzman had learned at the Charles William Harvey Studio that someone needed to be at the top.) As John Benson once put it, Humbug could be more accurately called a “commune” than a “co-op.”

However one describes it, the idea of artists putting out their own magazine was new in the world of mainstream professional publishing, just as the comic book and magazine versions of Mad and the Kurtzman-produced war comics had been new concepts. Those ideas had opened vistas of creativity and met with commercial success, emboldening the Humbug crew to try this innovative twist on the standard publishing model. “We all ended on a happy note where we somehow talked ourselves into [becoming] a union of artists to turn out [our] own magazine,” Kurtzman said. “That was Humbug.”2

But could they come up with enough money to get started? Yes, barely. According to surviving documents, Humbug Publishing Co., Inc. was funded with a mere $6,500 in capital. The largest investor was Arnold Roth, with $2,500; he had been doing well in the past couple of years. Al Jaffee ponied up all his savings: $1,500. Elder came up with $1,000 as did Kurtzman. Harry Chester kicked in $500. Only Jack Davis became a stockholder without helping fund the magazine. Even as the others would forgo payment until profits came rolling in, Davis asked for and got a guaranteed monthly salary of $125. Everyone agreed that Davis was invaluable, and there was no resentment toward him. Indeed, whatever the amount invested, all were issued the same number of shares. (The variances were probably considered inconsequential and could be equalized out of expected profits. The actual stock certificates were issued on May 17, 1957.)

A contrite Hugh Hefner played a part in helping them get started. He allowed them to operate out of the brownstone office for the time being, and soon offered Humbug space in Playboy’s advertising offices at 598 Madison Ave. For that, he charged them a mere $150 a month. Given the expense of office space in Manhattan, this was an enormous boon, even a de facto subsidy of sorts.

While dealing with a severe bout of chicken pox (in these years, he had one childhood disease after another), Kurtzman began looking for a printer and distributor who would work with them on a credit basis. No record exists of his travails in this regard, but the going was tough. In the aftermath of Collier’s failure, the mighty American News Corporation closed its wholesale periodical division. Many of the top magazines—Time, Life, Look, the New Yorker and Vogue, as well as Mad—were obliged to find new distributors. Amid the resulting turmoil, who in the industry wanted to bother helping one little magazine get started? Door after door was figuratively slammed in Kurtzman’s face until there was just one option left.

Charlton Publications, in Derby, Connecticut, was owned by two men who met in prison. John Santangelo, Sr., a Sicilian immigrant, was a former bricklayer whose first publishing endeavors resulted in a conviction for copyright infringement. While serving a year in the County of New Haven jail, he met Ed Levy, a disbarred lawyer, and the two of them decided to start a new publishing company. They called it Charlton after their two sons, both named Charles. It was to be an above-board organization, though a whiff of Mafia seemed to pervade Santangelo’s demeanor. (Many of the people behind the distribution and trucking of periodicals are said to have had ties to organized crime.)

Located on the Naugatuck River, Derby was and remains the smallest municipality in the state, covering a mere five square miles. The massive Charlton building stretched over seven-and-a-half acres, on land between a marsh and the railroad tracks. It housed a unique, all-in-one publishing facility that included front offices, editorial space, an engraving department, printing presses, a bindery and a distribution warehouse. The firm even had its own fleet of trucks. It made the bulk of its income by putting out all manner of cheap newsprint magazines, from puzzle books to coloring books to song-lyric books. (The long-running magazines Song Hits and Hit Parader were its most successful publications.) Undeterred by the coming of the Comics Code, Charlton pumped out a dizzying array of comic book titles, and was notorious for paying the lowest rates and having the worst printing in the business.

Desperate times make for exceedingly strange bedfellows. Since Charlton owned both its own printing plant and distribution company (Capital Distributing Company, or CDC), it could give Kurtzman what he needed. On the strength of the success of Mad, he was invited to Derby to meet with Santangelo and Levy. In mid-April, he and Harry Chester made the seventy-mile drive. After getting a gander at the mammoth presses, the editorial area (Charlton had an in-house staff of editors, writers and artists), and the cavernous distribution warehouse, Kurtzman was ushered into an office for the meeting. John Santangelo had already published an inconsequential imitation of the comic book Mad called Eh! Now he wanted to do a knockoff of Mad magazine. The Charlton mogul, who had an intimidating presence despite his broken English, wanted to hire the creator of Mad and his crew on a freelance basis.

When it became clear Kurtzman was looking for a printer and distributor for a creator-owned magazine, and that he was asking Charlton to perform those functions on a credit basis, Santangelo wasn’t happy, but he agreed to give Kurtzman what he wanted. If the new magazine could match the sales of Mad, Charlton stood to make a lot of money. Santangelo asked Levy to send Kurtzman an assignment agreement. The costs would be secured by the assets of Humbug Publishing Co., Inc., a not unusual arrangement. In better days for the industry, any number of new, undercapitalized comic book publishers started that way. (The only asset Humbug had, at this stage, was its name, but it would soon be generating editorial material that would be worth something.)

When Kurtzman left, he had mixed feelings. On the one hand, the magazine was now a go. On the other, he was nervous about working with Santangelo, and well aware of the poor quality of Charlton’s printing. He knew that Gaines tried having Charlton print Impact #1, the first New Direction comic book, and was so appalled by the poor printing job that he had all the copies pulped, and paid to have the book printed elsewhere. Of course, everyone was clear that this would be a magazine, not a comic book, but still . . .

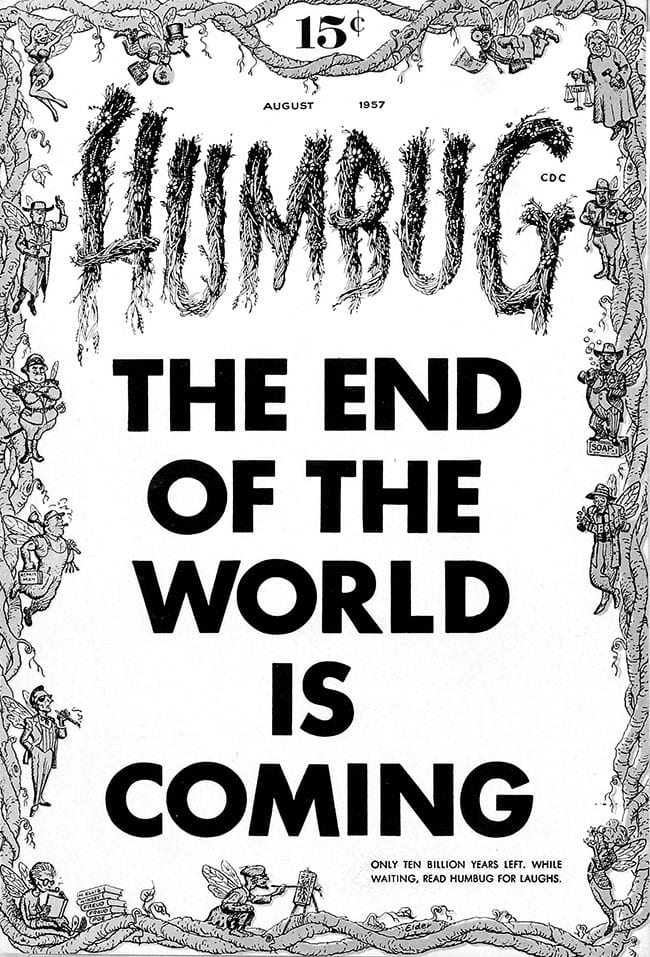

Naming the new magazine came easily, since Humbug had been one of Kurtzman’s title ideas for X. As for the format, he decided it would be different size than any other magazine on the stands in 1957: a 6 ½” x 9 ½” booklet. Beneath full-color covers, it would be printed in black and white with single color accents, mostly light blue or yellow (one color per issue). The magazine would have thirty-two pages plus covers, the same as comic books, and sell for fifteen cents. True, it would cost 50 percent more than the standard comic book, but Kurtzman felt Humbug should be priced in comparison to magazines, not comic books. It would have two-thirds as many pages as the twenty-five cent Mad, so it was priced accordingly. A monthly schedule was declared.

Why not make it the same size, price and frequency as Mad magazine? That was doubtless what Santangelo wanted, and logically it would seem to be the safest route, but Kurtzman wanted to try something new. He would never be an imitator, not even of himself. Trump had been highly conscious of its competitive stance vis-à-vis Mad. Although this wouldn’t be expressed overtly in Humbug, it’s probable that its format was an attempt to show that Kurtzman could be equally successful in a whole new way.

The new format had several virtues. In contrast to the black and white Mad, Humbug would have some interior color, have a lower cover price, and, as a monthly, deliver about one hundred pages more per year than the forty-eight page, bimonthly Mad. The use of limited color would minimize the matter of color registration (one of Charlton’s perennial problems). Two-color printing was simple enough that it wouldn’t require a separate colorist. Kurtzman probably felt the unusual size would help Humbug stand out from everything else. (Even smaller magazines, like Pageant and Reader’s Digest, worked on newsstands.) Once Kurtzman determined Humbug’s format, he announced it to his partners. As Al Jaffee put it, “He was not a great consulter. Harvey had visions.”3

As for the contents, Humbug wasn’t to be a continuation of Trump. Kurtzman now had to shift from a classy, slick high-end magazine with interior color to a humble two-color magazine printed on cheap pulp paper. No longer would he be trying to produce something geared to the Playboy reader. Instead, Humbug would be a sort of sophisticated college humor magazine. It would be geared to a slightly older readership than had Kurtzman’s Mad. While being limited technically, Humbug would be freer than Trump and smarter than Mad.

As soon as the stockholders of Humbug signed the agreement with CDC, work on the new magazine began. On April 2, Kurtzman wrote Hefner, “Together with Jack, Willy, Harry, Al and Arnold, I’m plunging ahead into our new venture and God knows where it will all end.” In that letter, Kurtzman itemized six items left over from Trump that would fit the new magazine. They included a four-page series of drawings by Davis of “little television screens showing TV boners,” pieces on model airplane and boat making, medicine in the US, a Du Maurier cigarette ad satire, a piece about the verbiage on cereal boxes and a one-page idea showing pictures of money that the reader could cut out and use. On April 17, Hefner responded:

The very best wishes to you and those strange ones you have gathered around you in your new venture. May [it] prove most prosperous and if things don’t work out for me here in Chicago, I may drop in on you in a year or two with an idea for a new magazine. Hoo ha!

I’ve affixed my official mark on your note regarding the material listed. We can work out the details on the matter when I next get to New York, but my thinking on the matter runs something like this—you will purchase the material from HMH for whatever it cost us to produce it in the first place. What we will have to work out when I see you is the method of payment. Some sort of part now, part later arrangement should be able to be worked out. I hope to be in New York the very early part of May and should have some time for talking and such.4

The ideas left over from Trump jump-started the creative process of Humbug. One thing would become clear: unlike Mad and Trump, Humbug would have almost no comment on, parody of or reference to comic books or strips, even in passing. Comic book publishers were closing their doors left and right in the aftermath of the Senate hearings and the establishment of the Comics Code. Since comics were in a tailspin, maybe even dying, satirizing them was pointless. Also, Humbug would have a sharper focus than its predecessor at EC. While Mad was about the ’50s as well as popular culture in general, Humbug would in most ways be specifically about 1957 (and, then, 1958).

Harry Chester handled the practical aspects of the start-up, and had a long list of things to tackle. He organized the bookkeeping system and ordered stationery. Harry contacted Wally Howarth at Playboy for advice on how to handle subscription fulfillment. He created a list of people and organizations to receive promotional and complimentary copies of the magazine, such as Steve Allen, Jack Paar and Ernie Kovacs. Chester was the one who arranged for the engraving to be done at Chemical Color, the company used by EC, rather than in-house at Charlton, ensuring a better result. “Harry was a very aggressive, hard-working guy,” Al Jaffee recalled. “He had a kind of entrepreneurial spirit, which is why Harvey chose him as our business manager. He was somebody that Harvey could always turn to and say, ‘Harry, while I’m dealing with the artists, you take care of the printing and production.’ It was a big job.”5 When all the elements for an issue of the magazine came in, Chester would put it all together based on Kurtzman’s layouts.

As before, Kurtzman often absented himself from the office, retreating to his home studio where he generated ideas, wrote and laid out stories, typed letters, and communicated by phone with Roth (in Philadelphia), Elder (in Englewood), Jaffee (on Long Island) and Davis (in Scarsdale), as well as others who did a little or a lot for the magazine, like Wallace Wood and Ed Fisher. Since there were limited funds to pay for outside work, most of Humbug was produced by its core group of stockholders. The monthly schedule forced Kurtzman to rely heavily on the talent and judgment of the group. Jaffee and Roth were listed as editors on the masthead. The do-overs and changes were kept to a minimum. That pleased Roth, who disliked Kurtzman’s proclivity for requesting changes in the work. “When I would have these conversations with Harvey, I would say, ‘If I do it over, it’s going to lose something. It’ll be tighter. I’ll correct certain things. Some things will be a little better, but it will kill the soul of the thing.’ It’s just the way I feel. It’s like playing in a jazz band. You know, if a guy’s going to take a jazz solo and the leader says, ‘I don’t want one false note,’ well, how free can you feel to just improvise?’” In this case, due to the time constraints, “[Harvey] really had to accept a lot of stuff and go with it even though he really wished it could be done three more times.”6

It wasn’t as if Kurtzman’s willingness to change things at the last minute never made a significant improvement. One instance involved the cover of Humbug #1 (August 1957). The proofs had been made for a cover that originally said, “ANOTHER NEW MAGAZINE” in red, with some text in the bottom corner to balance it out. When someone laughingly suggested it should be “THE END OF THE WORLD IS COMING,” Kurtzman liked it so much he had the cover changed. (He also took the opportunity to have Jack Davis design a new, more impressive title logo.) The final result was far more inspired and striking.

Under the masthead on p. 1, the headline announces, “Here we go again.” In response to an admiring letter from John C. Roberts of Wheatridge, Colorado, a typically downbeat Kurtzman wrote:

We don’t believe in standing still and letting the grass grow under our feet! Oh no! We’re going to spring into action, Mr. Roberts! We’re going to hustle on down to that Unemployment Insurance office for money. After that, we’re going to hustle back to work on our latest magazine, Humbug.

Humbug will be a responsible magazine. We won’t write for morons. We won’t do anything just to get laughs. We won’t be dirty. We won’t be grotesque. We won’t be in bad taste. We won’t sell any magazines.

The issue starts off with a parody of the movie Baby Doll. Tennessee Williams’ somewhat scandalous story of two Southern rivals for the affections of a sensuous nineteen-year-old virgin provided the basis for the first movie ever to be approved by Hollywood’s Production Code Authority while being given a “C” (condemned) rating by the Catholic Legion of Decency. “Doll-Baby” is Kurtzman and Davis at their best, with Davis’s likenesses of Carroll Baker, Karl Malden and Eli Wallach on target. A sequence with Baker and Wallach tiptoeing in and out of doorways in a hallway reached dizzying heights of absurdity when Walt Disney’s Goofy and other cartoon characters also tip-toe through the same doors and hallway.

Unlike Trump, Humbug would have a fair amount of political satire. For satire to work at its best, one must necessarily be familiar with the subjects in question. Many of the politically oriented items in Humbug, which depict public figures and events of 1957, tend to be obscure to readers decades later. That’s not to say that one can’t enjoy Arnold Roth’s “Bird Watchers Guide for Humbugians,” with its quasi-editorial cartoon drawings depicting Dwight D. Eisenhower, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Fulgencio Batista and others in bird form, simply for its graphic appeal, and the sly wording of the captions. The same is true of the “Pin-Up of the Month” showing portly labor leader Dave Beck reclining coyly at poolside. This pin-up, obviously inspired by Hefner’s Playboy centerfolds, is definitely grotesque—Humbug’s avowed editorial statement notwithstanding.

For his part, Al Jaffee contributed two of his most ingenious features in Humbug #1. The first is a cereal box opened and flattened out to show all printed surfaces, revealing an endless array of gimmicks, prizes, coupons, text fields and disclaimers. Next, his “Model Making” presents an incredible and yet seemingly feasible method of building models with a kit, in which all the pieces are connected by a piece of heavy string. “With this cleverly constructed kit the young craftsman need only give one good yank and all parts fly into place.”

Elder’s main bit in the issue is “Twenty-Win,” a Kurtzman-written parody of the popular Twenty-One television show, which would, a year later, be at the center of a giant scandal concerning rigged TV quiz programs. When Humbug #1 was published, the show’s star contestant Charles Van Doren, a college professor, was a household name, and the program was at its zenith. Elder is in top form, though rather constricted by the amount of dialogue, since the strip satirizes the complexity of the show’s rules. Work by Jack Davis, screenwriter Ken Englund, Ira Wallach, R.O. Blechman and even a bit by Wallace Wood make up the rest of Humbug’s first issue. The back cover is a subscription ad next to a fake five-dollar bill “as a subscription bonus” that appears to have been cut out of the page (with a simulated version of the interior page below “showing”). All in all, the first issue is nearly perfect. Everything works. It’s a propitious beginning that set the pattern for the issues that followed.

KURTZMAN AND CHESTER visited the plant to see the first printed copies of Humbug #1 come out of the bindery. As they beheld the first issue with its “THE END OF THE WORLD IS COMING” cover, they were confident it would grab the attention of browsers. When they got back to the city, copies were passed out to the participants who also reacted favorably. The size met with approval. As Arnold Roth said later, “I kind of liked the size, personally. I thought it was good. It was perfect.”7

Humbug received a bill from Charlton for the first issue on June 13, 1957. Some 297,055 copies were printed for a total cost of $5,049.94. The bill was marked “paid in full by Capital Distr. Co. per assignment agreement.” Now all that remained was for the magazine to take off. Kurtzman calculated that the book needed to sell about 50 percent of the copies to break even. If they could match the 65 percent sales of Trump, they would be in “deep clover.” As usual, there was nothing to do but wait until sales reports arrived.

Kurtzman met with the team monthly to hand out assignments and discuss pertinent matters. He would have the structure of the next issue in mind, with major pieces designed to relate to things like upcoming holidays, the sports seasons and political events. “He would block out what the people would be responsible for,” Roth recalled. “Where there were gaps, he would say, ‘We’ll have to fill this. We’ll have to do that.’ Those decisions came very quickly. Sometimes he would call me and ask me to do something overnight.”8

Despite having little to pay for outside talent, one new writer turned up who became one of the magazine’s best. He wasn’t really an outsider. Larry Siegel met Kurtzman while manning the HMH promotions office that shared space with Trump in the Thirty-Seventh Street brownstone. Siegel had been editor of Shaft, the University of Illinois satire magazine that had once, in the late 1940s, been edited by Hefner. While he continued doing the promotional work, Siegel asked Kurtzman if he could write for the new magazine. With “Something of Mau Mau,” a satire of Robert Roark’s violent Something of Value, Siegel immediately showed himself to be a clever satirist and became a regular contributor to Humbug. “I never got into one of those group things that they used to have with Jaffee, Elder, Jack Davis and the rest of them,” Siegel recalled. “I would get together with [Harvey], and I would make some suggestions, or he might say, ‘Why don’t you do something on Peyton Place?’ He was a very easy guy for me to work with. He was an absolute doll, that’s all I can say.”9

Along with Siegel’s piece, Humbug #2 offers the Kurtzman-Elder film parody “Around the Days in 80 Worlds,” as well as a cartoon of Groucho Marx accompanying a piece by British novelist and playwright Alex Atkinson (reprinted from Punch) which expertly captures Groucho’s comic persona. Jack Davis teams up with Kurtzman to satirize the smash Broadway show My Fair Lady (“My Fair Sadie”) and “Television Bugs,” a look at typical goofs made during live TV broadcasts of drama programs. A new ongoing feature by Arnold Roth called “The Humbug Award” appears (“Dedicated to outstanding people who have made extremely unimportant contributions to society”), given in this issue to Robert Harrison, editor of sleazy Confidential magazine. By the time the first two issues were finished, Kurtzman and company were settled in their new offices on Madison Avenue.

Humbug #3 is the first issue with a letter column. There are missives from Bhob Stewart and George Metzger, the future underground comix artist. (“Underground comix,” spelled with an x to distinguish them from the Comics Code-approved comic books of the time, were 1960s–70s self- or small press-published comics that defied taboos and were mainly distributed through tabloids, head shops and the mail.) Humbug quickly became a cause célèbre among readers who had followed Kurtzman from Mad to Trump and then to the new magazine, and recognized that something extraordinary was happening: Kurtzman and crew were producing a more evolved, more intelligent satire magazine than Mad. A trickle of letters at the start quickly became a flood, with dozens arriving on some days. As with the early days of Mad in 1952, the letters convinced Kurtzman that they had struck a nerve.

ABOUT THIS TIME, Kurtzman discovered the Okeh Laughing Record, a 78 rpm record released in 1922. It begins with the sound of a mournful trumpet playing, then the sound of a woman’s laughter, who is then joined by a man who is also laughing uncontrollably, and so goes on for almost three minutes. Kurtzman loved to play it for friends and visitors. Its laughter was always contagious. On a few occasions, Arnold Roth slept on their couch after late-night sessions finishing an issue of Humbug. In the morning, Kurtzman would wake him up with the laughing record, turned up full volume. The second or third time it happened, Roth said, “Why are you playing it for me again? I’ve already heard it.” Kurtzman replied, “It gets better.”10

JUST AS THE COVER of Mad #11 parodies Life magazine, Will Elder’s cover of Humbug #4 (November), featuring Queen Victoria, parodies Time. In the opening editorial, Kurtzman wrote, “Mail is rustling into the office at an accelerating rate of one-hundred plus letters a week. We’ve inked a pact for a Humbug paper-bound book which will appear in November.” A letter on that same page from Ray Russell of Playboy magazine reads, “Of the four leading American humorists (you, me, S. J. Perelman and Louella Parsons) none better deserves the acclaim and recognition of the masses than me. You’re next though. And I say this from a heart filled with sincerity, warmth, regard, esteem and professional jealousy. Viva Kurtzman! Long live Humbug!” The quality of the material in Humbug was consistently high, and the issues were on time. The movie and television parodies continued to be drawn by Davis and Elder, with Roth doing most of the politically oriented material. Larry Siegel branched out into humorous poems and song parodies, as well as book and magazine satires (“Consumer Retorts”), and Al Jaffee zeroed in on absurd aspects of the American scene.

Jaffee later discussed his working method for Humbug. “I never felt that my proposing an idea for an article was ever going to be really successful. I decided . . . that I would invest in speculating and draw out my entire article. But I [did] it on lots of pieces of paper, and Harvey would assemble it into an article. Because I had an opening, and then I had a dozen ideas to go with it. He would put it together and arrange it, and it worked very well that way.”11

Meanwhile, no one would be paid for their efforts until and if the magazine was profitable. Each of the players handled the situation in his own way. Kurtzman could collect New York State unemployment benefits for twenty-six weeks, but was counting on royalties for the Mad paperback books to get him through. When he was still at Mad, and Gaines ran into financial difficulties, Kurtzman agreed to temporarily forgo payment. According to his estimate, Gaines owed him about $2,000 for paperbacks sold when he was still at EC, and probably a similar amount in the months after he left.12 (Those sales would only accelerate in the coming years, ultimately bringing Kurtzman’s collaborations—which dominated the early paperbacks—to millions who hadn’t seen them in the original comic books.) He wrote to Gaines, reminding him of the debt and asking to be paid. The only monies Humbug was generating for the stockholders were advance payments on royalties for The Humbug Digest ($2,500, received in April 1957, probably used for ongoing production expense), and whatever orders for magazine subscriptions arrived in the mail.

Arnold Roth and Jack Davis worked on assignments for other publications in order to pay the bills (or, in Davis’s case, to augment what he was getting from Humbug). Al Jaffee did not, and was strangely serene about making no money on Humbug for months on end. “I was at a party and I remember someone saying to me, ‘You’re working on this magazine Humbug. How long have you been on it?’ At that time I think it was six or seven months. ‘And you don’t get a salary?’ So I said, ‘No, I don’t.’ For so many years I was grinding stuff out, the comic book stuff. I said, ‘I’ve never felt so at peace and so relaxed and so unworried as I am in this situation.’”13 Deep down, he had faith that Kurtzman would pull them through and the magazine would become successful. In the meantime, having invested all his savings in Humbug, he was borrowing against a personal insurance policy.

The process of producing the magazine itself was a good experience for all concerned. The creative work was stimulating and satisfying. They knew they were generating something good, and enjoyed each other’s work immensely. Kurtzman and Chester were closer than ever. “We used to have great times going [to Derby],” Kurtzman said. “Harry and I would take the trip regularly to see our book go to press.”14 The Humbug editorial meetings were rife with laughter, though Kurtzman was mainly the audience for the jests of others. A master of satiric humor on paper, he was never a teller of jokes. Roth recalled,

Once when things were getting a bit depressing after a few issues of Humbug, Harvey was giving us all a sort of pep talk. Harvey’s back was to the windows. About eighty feet away there was another building at least as high as ours. We were looking at Harvey and he waved his arm to the window and said, “Remember, they’re all out there.” Like in a movie all our eyes went to the end of his hand and out the window. Right across in the window of the other building there was a guy screwing a woman on a couch. We all leapt to the window. He didn’t know what the hell we were doing.15

Kurtzman kept former contributors to Mad such as Doodles Weaver abreast of the status of the new magazine. In October, he wrote, “Right now, we’re barely eking out a living. I’m trying to publish Humbug with my own shoestring. We’ve got a great system for handling the writing. A little midget is chained to a desk and if he doesn’t write funny, I beat him till he does, and he works very cheap. He pays me.”16

All were frustrated by the lack of sales reports. Based on scattered information, Capital Distributors estimated that Humbug #1 sold roughly 45 percent (about 135,000 copies) of its print run. If true, this was disappointing, but it did mean they weren’t too far from being a going concern. It was the final sales report that really mattered. When it arrived, in mid-October, it documented sales of only 35 percent, which would normally be cause for immediate cancellation. But Capital Distributing informed Kurtzman that issues #2, 3 and 4 were seeing a consecutively steady rise in sales. Also, the sale on #1 was eccentric from town to town, which wasn’t typical of a flop magazine. It suggested to Kurtzman that there were problems on the distribution rather than the buyer level. “It’s all very mysterious,” he wrote Ed Fisher, “but our distributor . . . seems to see enough [potential] to give us an assist through issue #8.”17 In a follow-up letter to Fisher a few weeks later, he wrote, “The world is upside down. We’re God-knows how many thousand dollars in debt and Mad continues to grow like some horrible Frankenstein monster. But there is still hope. Playboy has printed a lovely twelve-page article on us. Ballantine has printed a Humbug pocket book. If we can hold out for another half year, I think we’ll be in! The publishing world is an astonishing place!”18

Humbug’s failure weighed heavily on Kurtzman, leading to a dark period in his career. He returned to freelancing, as he had in the year before he met Bill Gaines.

Chapter 19

1 James, “Hey Look! An Interview with Harvey Kurtzman,” 47.

2 Ibid.

3 Benson, “Roth & Jaffee,” Humbug, Book One, 190.

4 Hefner letter to Kurtzman, April 17, 1957. All Humbug correspondence is from the Kurtzman archives.

5 Al Jaffee, interview with author.

6 Benson, “Roth & Jaffee,” Humbug, Book One, 198.

7 Ibid, 190.

8 Ibid, 199–200.

9 John Benson, editor, “Larry Siegel Talks about Harvey Kurtzman,” by Grant Geissman, Squa Tront #12, 24.

10 Arnold Roth, interview with author, 2011.

11 Benson, “Roth & Jaffee,” Humbug, Book One, 203-4.

12 According to a note written ca. 1958 by Kurtzman among legal papers pertaining to the EC/Gaines lawsuit.

13 Benson, “Roth & Jaffee,” Humbug, Book One, 211.

14 Benson, “A Conversation with Harvey Kurtzman and Harry Chester,” 42.

15 Gary Groth, “Take Five” interview with Arnold Roth, The Comics Journal #142 (June 1991), 70.

16 Kurtzman letter to Doodles Weaver, October 31, 1957.

17 Kurtzman letter to Ed Fisher, October 31, 1957.

18 Kurtzman letter to Ed Fisher, November 22, 1957.