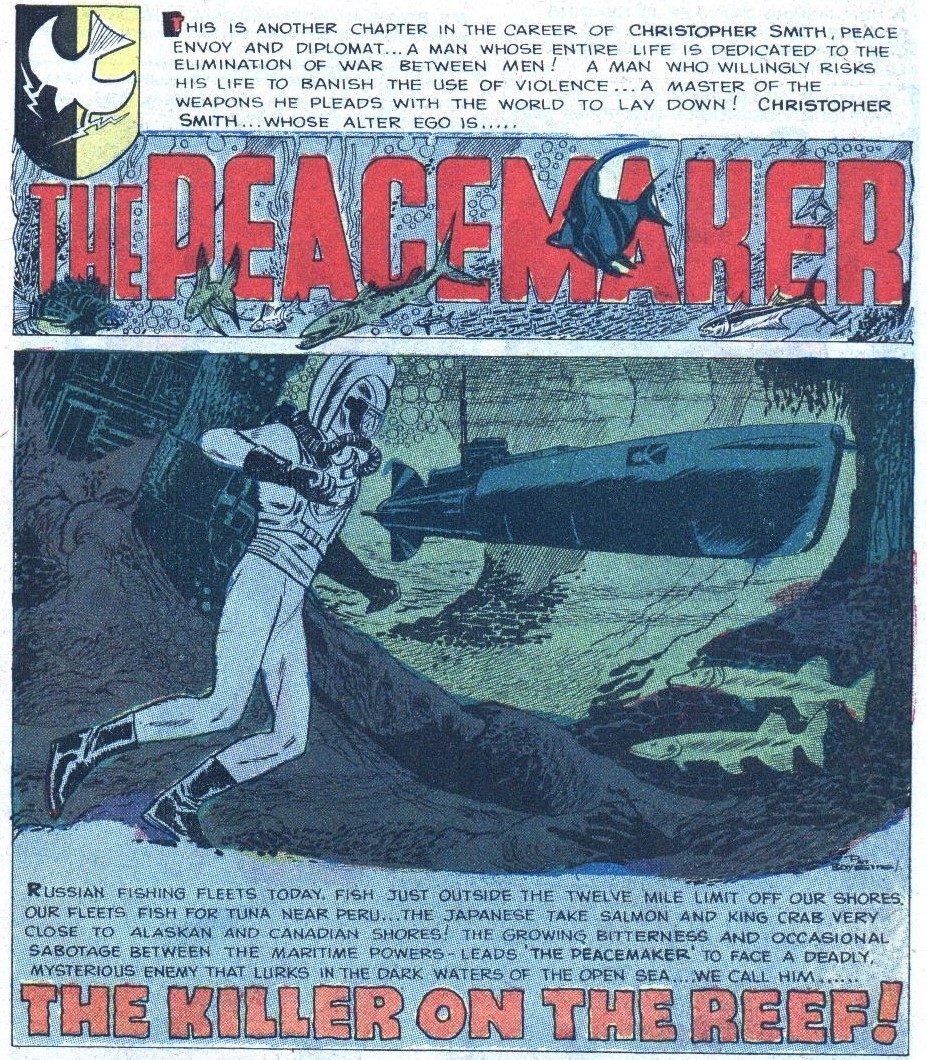

Originally conceived by Joe Gill (sometimes referred to as the most prolific writer in comics) and Pat Boyette, Peacemaker was another in a long line of Charlton Comics creations mostly noted for their great design and less for their great story. Christopher Smith, a nice guy American diplomat, finds himself donning red and white tights and an amazing helmet (a design worthy of Kirby) to take on all manner of warlords and super-criminals as “the man who loves peace so much he’s willing to fight for it.” This inherent contradiction in terms wasn’t pushed too hard - Smith’s early adventures are a pretty bloodless affair and he tries to keep his enemies alive.

If the character stands for anything it's for America’s vision of itself post-WWII, the great policeman of civilization – bringing order to a chaotic world. In the second story of The Peacemaker #1 (March 1967), a diplomat from “a minor Balkan nation” slaps Christopher Smith in the face in a show of bravado; Christopher, certain of his own prowess (personal and national), lets the incident slip. Why should he worry? Let the mouse roar. In that manner, the series offers even more contempt for would-be rivals in global dominance than the actual America of that age; when Lyndon Johnson had a ‘disagreement’ with Greece over the Cyprus issue he didn’t hold his tongue. “Fuck your parliament and your constitution. America is an elephant. Cyprus is a flea. Greece is a flea. If these two fleas continue itching the elephant, they may just get whacked good...” A dream hero for a dream America, aiming to serve the same inspirational role Captain America served decades before.

That Peacemaker didn’t have much of a personality is forgivable (this is a B-list cape comic after all), but the lack of interesting antagonists or supporting cast is less so; the series didn’t make it past five issues. Like other Charlton creations, he was picked up by the DC in the mid 1980s and was given to Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons for Watchmen... before the company realized the series would do the single worst thing a cape comic can do to a character – wrap up their storylines. So Peacemaker was turned into the Comedian and, other than a brief appearance in Crisis on Infinite Earths #12, was kept aside for a more profit-minded venture.

Enter Paul Kupperberg, the then-current writer of DC’s most generic-sounding (and generically-designed) character, Adrian Smith - the Vigilante. Kupperberg introduced a new version of Peacemaker in a storyline taking place in Vigilante #36-38. It's unclear if Watchmen's Comedian character influenced Kupperberg's Peacemaker; while the two feel oddly similar, Kupperberg contends that it was simply part of the general approach at the time (the timeline between Watchmen and the Vigilante storyline is rather compressed). This Christopher Smith is now “a man who loves peace so much he’s willing to kill for it.” In his introductory issue he guns down a number of terrorists hijacking a plane - as well as the replacement Vigilante (Adrian’s friend), for daring to stand in his way. Chase swears to hunt the Peacemaker down, but ends up teaming with him against a larger threat. As the storyline progresses, Peacemaker becomes more unhinged - talking to voices in the air (he’s convinced his helmet holds the souls of those who died next to it) and becoming convinced his handler is part of a secret terrorist plot that he must destroy.

Obviously, Kupperberg is mocking this sort of Reagan-era action hero, in both form and rhetoric. Peacemaker is unwell; his talk about ensuring peace is but a justification for his violent impulses. What else can one make of a scene taking place in a bar of ‘regular Americans’ watching news footage of Vigilante and Peacemaker fighting a group of terrorists and becoming filled with racial hatred, storming out with masks and weapons to ‘kill the Arabs’? Except, the story does portray a terrorist plot in the middle of a large American city - a plot that is only foiled thanks to application of deadly force by American vigilantes. There isn’t a singular positive portrayal of an Arab character in these issues. It’s like one of these post 9/11 television series that made a show about being morally complex while mostly indulging in blowing shit up in a slightly more drab manner than before.

If anything, Tod Smith’s excellent action artwork in issues #37-38, big on unusual angles and dramatic poses, only accentuates the reactionary elements of the story. He’s just too good at drawing manly man blowing shit up, employing dirty back alleys of the city or crowded highways for chase scenes. His work ends up accentuating the very elements Kupperberg’s writing is trying to subvert (or, at least, engage with on a deeper level). But it’s hard to complain too much, considering said artwork is the best part of that series. Vigilante might have been a generic design, but Smith gives the artwork a personality of its own – almost worth the price of admission by itself.

There was a whole line of DC books around that period which felt of a kind, the morally-grey clock-and-dagger spycraft superheroes. Vigilante, Checkmate, Captain Atom, Manhunter and, of course, Suicide Squad. All of these portrayed morally dubious characters in the clutches of the military-industrial complex, bad people making bad decisions for the greater good. But, apart from Suicide Squad, none of them managed to square the circle of presenting protagonists the audience wants to root for while showing them doing dirty deeds. These characters usually ended up being more James Bond than George Smiley, happily blowing bad guys away – their own worst excess justified by the general nefariousness of their enemies.

This is never clearer than in the four-issue Peacemaker miniseries that followed the character's storyline in Vigilante - still written by Kupperberg and drawn by Smith, with inks by Pablo Marcos, coloring by Gene D’Angelo and lettering by John Costanza & Albert T. DeGuzman. Oddly, the series has never been reprinted; even now that the Peacemaker character is a part of large Warner Bros. film (The Suicide Squad) and is about to star in his own TV show (played by human action figure John Cena), there are no signs of a collection appearing any time soon. Hunting through back issue bins—assuming some greedy speculator hasn’t scooped them up beforehand—or surrendering to the might of the comiXology machine is the only legal way to read these tales to astonish.

I’d be more than happy to tell you that the series is simply too edgy and controversial to be properly reprinted, that the stuff is potential dynamite, that DC is too cowardly to engage with it... but alas, it is not so. There’s some offensive yellow peril stuff, courtesy of the antagonist Doctor Tzin Tzin (seemingly only named so that issue #2 could do a ‘Wages of Sin’ pun), but, sad as it is, that's nothing out of ordinary for serialized American comics. (I was about to write ‘for that period’, but let’s not be too generous to the current era.) The Doctor is a generic terrorist leader, seeking to make the Cold War hot—a pretty generic notion even then—by creating a series of crises between the two sides of the Iron Curtain. The only person who can stop him, because for some reason the rest of DC’s intelligence and military super-people appear to be on vacation, is the Peacemaker. That is, if he can keep his head screwed on straight.

The talking-to-the-dead-people-in-his-helmet gimmick is abandoned thanks to some techno-babble; instead, Smith must deal with one ghost only – that of his late father, who happened to have been a high-ranking and particularly sadistic Nazi. That’s a good concept; it provides personal drama as the All American hero struggles with what he wishes to be, versus what he perceives as his dirty ‘legacy’. Peacemaker feels personally tainted; everything he does, nearly killing himself over and over again, is a response to that. Imagine the Spider-Man guilt complex magnified a thousand times over and fed through a patriotic lens. Except, the voice egging Peacemaker on isn’t a kindly old uncle Ben, but a sadistic concentration camp guard.

On a metaphorical level, it allows Peacemaker to deal with the tarnished legacy of the United States following World War II; the way so many Nazis not only escaped justice, but were allowed to prosper even after their crimes have been exposed. Recent books such as Hitler’s American Model have made a good showing of the tangled relations between the two nations even before the war, showing a country that only pretended to have been innocent. In the right hands, this is potentially great material for fiction, especially suited for cape comics and their inherent iconic nature – even with B- and C-level characters, the readers can easily get the sense that these figures are a stand-in for something greater than the self. Sadly, those hands turned out to be Garth Ennis’ and Killian Plunkett’s.

The Peacemaker miniseries ends up being a sort of a disappointment—assuming you (like me) had actually expected something—being both over-written (a frequent problem for Kupperberg, who enjoys complicating his plots) and unfulfilling. It’s just four issues long, but feels much longer - still carrying on that Bronze Age flab of exposition-speak without actually going anywhere with it. You keep expecting to see some sort of connection, on a storytelling level, between Peacemaker and Tzin Tzin that would illuminate Smith’s inner problems. But Tzin Tizn is a non-entity, just a boss figure that exists to send one underling after another to die by Peacemaker’s bullets.

On a macro level, the themes aren’t so much addressed as they are brought up. The USA government is dependent on one mentally unstable individual who is constantly manipulated by his superiors, fighting to serve values that exist only in his mind. The ‘peace’ he fights for is just two empires carving the rest of planet as they see fit. But any notion of criticism goes out the window because Peacemaker’s enemies really are out to destabilize any notion are peace; they are that bad, and the government ends up entirely justified in pushing Christopher Smith so far - if they didn’t, he wouldn’t be able to save the day. It's just like the surface criticism offered in Vigilante; either the creators weren't able to go far enough, or editorial stopped them.

On the micro level, the story just isn’t very satisfying. Even Tod Smith and Pablo Marcos’ contributions feel slight compared to the Vigilante issues. The scale of the action is too big; by the fourth issue whole armies clash in the background, yet the Arnold Schwarzenegger-ness of it all doesn’t allow the art to indulge in the more personal aspect of the action. There are some nice bits and pieces, though; this was still the period when people making action comics (as opposed to Action Comics) were expected to think through the choreography of their set pieces, rather than just do a series of post-Jim Lee poses.

Suicide Squad might not be a fair comparison; it is DC’s best series of that decade (if not of all time), and a hard bar to clear. But Suicide Squad did manage to balance the cynicism of systemic critique with personal development of its protagonists. It never mistook empathy for sympathy. The title was empathetic toward Amanda Waller’s personal struggle to advance in a world that refused to recognize her while doing what she believed necessary... but it still recognized that most of her efforts were for naught: bad actions in service of bad masters. The same is true for Rick Flag’s uber-patriotism and his desire to please his daddy - in many ways, a better version of Peacemaker’s character arc.

Peacemaker, comparatively, has only one real character to deal with - both his support crew and personal handler are nothing but ciphers, unable to elevate him above the pitch-line. There’s just so much there, but the story is too obsessed with plot machinations to truly explore the psychological depths offered by the premise. One fight scene follows another, and while the creative team at least tries to diversify their set pieces—hand-to-hand; aerial combat; enough bullet casings to cover the entire John Woo oeuvre—none of it really sticks to mind.

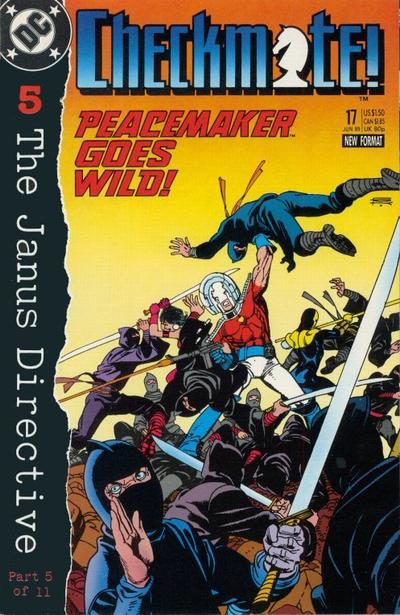

When the series is over and Peacemaker appears, alive and well, we are meant to understand he has undergone some positive change, but... we haven't seen any of the process leading to this. The story is over, so the text just says he’s better now to give a sense that something was achieved (though there is the inevitable sequel hook). A couple of months later, Peacemaker would re-appear in Checkmate as part of the “Janus Directive” crossover, once again as his generic murderous ultra-patriotic self (despite still being written by Kupperberg). Maybe Kupperberg thought the character was better off in small doses as someone for others to react to, rather than as a headliner. Maybe he recognized the powers-that-be wouldn’t let him make Christopher Smith ‘well’, as that would render him just as unusable as his Watchmen counterpart. Maybe it’s meant as a comment on the inability of the United States to acknowledge its historical mistakes and atrocities (this is me being very generous).

Still, despite its many problems, I am sad Peacemaker isn’t in print. There’s a certain baseline quality to DC comics of that period so that even the ‘bad’ ones rise above the rabble. Kupperberg’s reach as a writer often exceeded his grasp, but at least he had a reach. Being ‘over-written’ is bad, but I’ll take that any day over today's version of the same comics, which tend to be under-written: issues read in less than five minutes, lingering in your mind for about as long after. Kupperberg is a man who lived in the post-Watchmen landscape and saw it not as a reason to let go of cape comics, but as a challenge to make them better. That we would all fuck up in service of such notions.