1.

Following the conclusion of Batman: Year One and Elektra: Assassin in 1987, Frank Miller, like Alan Moore, left the Big Two and dropped off the radar. He was by no means idle - he drew covers and wrote introductions for First Comics’ Lone Wolf and Cub (the classic manga by Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima was being reprinted in the same prestige format as The Dark Knight Returns) and did various pin-ups and short pieces – but his next major work, Give Me Liberty illustrated by Dave Gibbons, wasn’t released until 1990.[i]

Despite its long gestation period, Give Me Liberty was actually conceived in the summer of 1988 at the height of the Watchmen and Dark Knight hysteria. As Miller explained, “Dave and I were at the San Diego convention, walking around the San Diego Zoo, and we started talking about working together. He had just finished Watchmen, I had just finished Dark Knight—I suspect we were both taking our press awfully seriously and had yet to calm down.”

But despite their initial enthusiasm, the series was shelved for a couple years. Miller recalled that he was “just writing scenes at random” without a clear idea of what he wanted to say and, eventually “Dave quit.” “It was originally going to be a huge portentous series of 150-page graphic novels, the first of which I scripted (but) the wind just went right out of our sails. We lost interest.”

Ultimately, with Lynn Varley’s encouragement (“It took Lynn to straighten my brain out”), Miller resurrected the series, but he decided to “reconfigure” it by “bring(ing) absurdity and sarcasm and adventure and joy to it.” In other words, he lightened up and tried to make it fun by returning to his first love: superheroes.

2.

However, even with Miller’s efforts to soften the story, its political roots push through. The title, of course, is a reference to one of the most famous quotes in U.S. history. According to Wikipedia, “’Give me liberty, or give me death!’ is . . . attributed to Patrick Henry from a speech he made to the Second Virginia Convention on March 23, 1775 (which) swung the balance in convincing the convention to pass a resolution delivering Virginian troops for the Revolutionary War.” These seven words were a rallying cry so stirring and powerful, their sentiment so deeply resonant, that it has echoed down through generations. “Give me liberty” has become an iconic, immortal phrase in the lexicon of the American psyche, a concise expression of the country’s spirit of independence.

Yet, in Miller’s cynical hands, this ideal of democracy has been corrupted beyond recognition. The world depicted in the story portrays a uniquely American style of capitalist fascism where corporations, rather than dictators, rule the country. President Lincoln’s vision of a “government of the people, by the people, for the people” has been corrupted by a ruling elite whose only motivation is profit, and the military-industrial complex has become the predominant force in American politics. In one telling example, a giant Fat Burger robot, which Gibbons based on the iconic Shoney’s Big Boy restaurant mascot, unleashes an arsenal of high-tech weaponry in the Amazon rainforest. The scene is an absurd depiction of unchecked corporate greed.

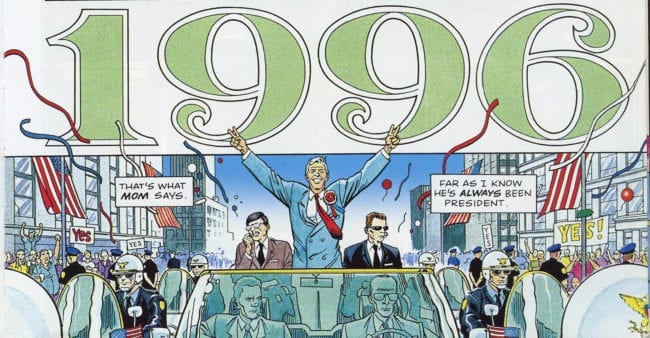

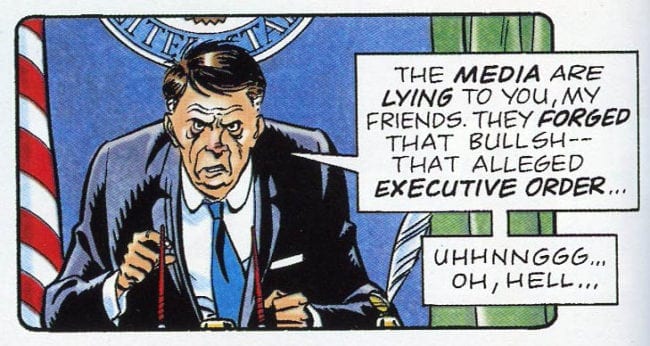

Perhaps the most powerful example of the story’s cynicism is the character, Howard Nissen (whose name is a play on Richard Nixon), a liberal democrat thrust into the highest office after a terrorist attack incapacitated President Rexall (the endlessly smirking Reagan-esque conservative). Inexperienced and unprepared, Nissen nevertheless implemented a sweeping series of populist reforms that were so popular, he was dubbed “the savior of the soul of America.” Yet, by the story’s end, the corruption and pressures of the office have reduced him to an alcoholic paranoid disgrace, and he is eventually assassinated in a military coup. Nissen’s tragic rise and fall illustrates Miller’s deeply pessimistic view that America is beyond saving.

3.

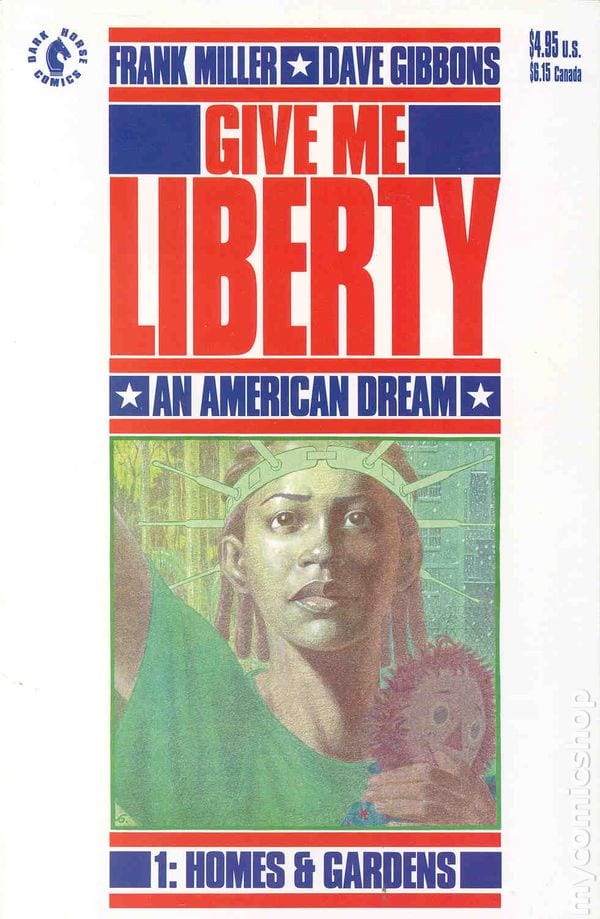

Against this bleak backdrop, we meet the story’s unlikely hero, Martha Washington. There is a bitter, if somewhat obvious irony in naming the protagonist after the nation’s original First Lady, a privileged white woman. Miller’s version of Martha (whose character was inspired in part by Horatio Alger’s classic rags-to-riches stories) is a poor black woman born and raised in “the Green,” an abbreviation for Cabrini Green, Chicago’s infamous public housing project.

Starting with her birth, the first issue and a half tells Martha’s coming-of-age story during the collapse of American democracy, but by the middle of the second issue, Martha’s origin story reaches its natural conclusion: after returning home from the war in the Amazon, she is honored as a hero by the President and then reunited with her family.

From that point forward, the story takes a sharp turn. On the very next page, Martha is suddenly in the middle of a space battle (when and how she became an astronaut is never discussed), and saves the world from being destroyed by an orbiting laser canon by single-handedly murdering a crew of gay Nazi terrorists with nothing but a sword.

This transition is jarring, but, as Miller noted, the dramatic shift in Martha’s character was the plan. In his Introduction to The Life and Times of Martha Washington, he wrote that he had “mischronicled (Martha’s) first adventure as something too on-the-nose political, too self-consciously serious, and, in a word, dreary.” Rather, with this conscious shift in focus, he wanted Give Me Liberty “to be the story of a hero.”

Gibbons echoed similar sentiments in his Introduction to The Life and Times of Martha Washington. “In some ways, Martha is an alternate-world version of the traditional patriotic comic book hero . . . Captain America.” Miller also likened Martha to Captain America, describing her as “someone who very fiercely protects certain democratic ideals,” however, in many respects she more closely resembles his signature character, the Dark Knight. Like Bruce Wayne, Martha isn’t super-powered, but has the same physical and psychological abilities as Batman. According to Miller, “With Martha, one of the things I tried to get across is that she has, across the series, an increasingly disciplined mind to the point where it’s almost superhuman.”

Not surprisingly, she also resembles Daredevil, particularly in “Born Again.” Like Matt Murdock, Miller is excessively harsh in his treatment of Martha. Throughout the story, she is dropped into one sadistic situation after another. In just four issues, she is imprisoned, tortured, blinded, sexually assaulted, drugged, beaten, shot (multiple times), humiliated, experimented on, and memory-wiped. Yet despite the many indignities she suffers, she somehow remains resilient and morally grounded. Like a true superhero, she gets up after every punch, but, again like Batman, these endless brutal experiences turn her cold and joyless. In the final scene, she sits calmly, without any hint of emotion, as her adversary hangs himself in front of her.

Not surprisingly, she also resembles Daredevil, particularly in “Born Again.” Like Matt Murdock, Miller is excessively harsh in his treatment of Martha. Throughout the story, she is dropped into one sadistic situation after another. In just four issues, she is imprisoned, tortured, blinded, sexually assaulted, drugged, beaten, shot (multiple times), humiliated, experimented on, and memory-wiped. Yet despite the many indignities she suffers, she somehow remains resilient and morally grounded. Like a true superhero, she gets up after every punch, but, again like Batman, these endless brutal experiences turn her cold and joyless. In the final scene, she sits calmly, without any hint of emotion, as her adversary hangs himself in front of her.

Unfortunately, reshaping Martha’s story into a superhero narrative made it too formulaic. The rich portrait of a fallen America that Miller and Gibbons established in the first issues fades to the background by the end. Instead, the second half of the story is a predictable over-the-top sci-fi adventure packed with comic book clichés like brain transfers, jungle adventures, false memory implants, and so forth.[ii]

4.

Given its creators, it’s no surprise that Give Me Liberty reads like a combination of Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. For example, Martha’s dispassionate and fragmented narration (as well as Raggy Ann’s and the Surgeon General’s) gives the story a staccato rhythm reminiscent of Rorschach’s clipped, psychotic journals. Like both books, propaganda is also central in building the dystopian setting. Miller, who describes himself as “a big news junkie,” used magazine articles, newspaper headlines, and television talk shows to portray the story’s political, social, and economic context.

Yet unlike Alan Moore’s densely plotted story, Miller’s comparatively sparse script let Gibbons’ art breathe, calling for larger panels and full-page splashes. Miller also trusted Gibbons to handle the storytelling in several extended silent scenes. Gibbons explained the difference between the two writers’ approaches. “Alan is comparable to a classical composer—a Mozart, if you will—who seems to have every note of vast symphonies mapped out in his head. Frank, on the other hand, is like a jazz virtuoso, a Miles Davis, with impeccable technical skill but ready to leap off on a flight of fancy or an unexpected riff if the whim takes him.”

In a 2017 New York Times interview, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, Viet Thanh Nguyen, claimed that “(Give Me Liberty) long ago predicted presidents like Donald Trump.” There are certainly some intriguing parallels between the fiction of 1990 and the reality of 2018. In one panel, for example, President Nissen berates reporters, claiming that the media is making up lies about him. There’s also the requisite dystopian themes of poverty, racism, corruption, militarization, and environmental collapse (the Statue of Liberty is submerged up to her robes due to the rising ocean levels). But whether it’s fair to label the series as a visionary work is beside the point.[iii] While it never rises to the level of Watchmen or The Dark Knight Returns, Give Me Liberty’s ultimate legacy is as a blistering indictment of modern politics. Miller and Gibbons so credibly envisioned Martha’s shattered world, the story still resonates nearly three decades later.