Gary Panter, as readers of The Comics Journal should know, is one of cartooning's absolute masters. His new book Songy of Paradise follows a delusional hillbilly named Songy on his vision quest where he's tempted by a Satan-like shape-shifting creature. I spoke to Panter over the phone about Songy and his research for it as a Cullman Center Fellow at the New York Public Library.

Dash Shaw: Why Songy now and not Jimbo? Who’s Songy?

Gary Panter: I have a long Jimbo book in progress that might be called Jimbo and Friends, which features eight-page stories of Jimbo and other actors in his world on Mars. Songy is one of three hillbilly relations—a brother named Yo-yo and a psycho cousin named Henry. My mother was from a coal mining town in Oklahoma, and my father was from a Choctaw town on the other side of a small mountain range. It was very rustic there in my childhood visiting relations.

But, for this story, isn’t it because Songy is wiser than Jimbo, and Jimbo would’ve said OK to this devil? [Panter laughs] It would’ve been a completely different story.

Yeah, I never thought about using Jimbo in this story. I needed a real ignorant, stubborn person. And it had to do with the look, too. Jimbo is real striking to me, he’s almost hard to fit in my comics, because he’s almost human proportions and he’s freckle-faced and he’s just pretty distinctive, so if something’s about him, it’s really gonna be about him, and this was really gonna be about Milton and Jesus and this idea of Satan.

Isn’t it also that Songy is older? Jimbo is forever the age of Bazooka Joe.

Yeah. And if Jimbo went to the desert to starve, it would be grotesque. If I started drawing Jimbo skinny and stuff. Again, he would just demand too much of the stage, I needed someone who would just fit into the story. And that was sort of the whole Dante thing, I think Jimbo shows up there for a second maybe in those books, but really it’s not... I’m totally forgetting that he’s all over this book. I dunno, my brain is full of this stuff by now, I’m usually thinking about the new project.

I know you’ve kind of done this before, but this story struck me as notable for you for having a very clear beginning, middle, and end. [Laughs]

It’s true. I do that, and I’ve done that more and more recently. Another new comic I’ve been drawing is completely coherent and completely traditional in terms of emotional payoffs and stuff. I’ve spent a lot of my career doing these formalist exercises, and it’s something I wanted to do because it’s related to modern art, but they can be cold, y’know.

So why do you think recently you're into this more conventional structure?

I think it’s because I’ve explored the other stuff enough. Like Dal Tokyo, I really exhausted the formalities of the typical four-panel strip, and really, emotionally, it’s also probably part of my age. I raised a daughter, I’ve been married and divorced, my parents died. So there’s a lot to think about just in terms of emotions. And just to try to keep moving. I don’t want to be a person that’s just nailing the same nail in over and over.

When you say you’ve gone through all of that, are you saying that that makes a beginning, middle, ending story more appealing or just that you want to move on to something else?

Well, it’s a bit of a mystery to me, but I do think that if you’ve neglected conventions it might be time to explore them. And there’s really a way to abuse conventions. I could do formalism about conventions, and that would kind of be like, “Oh, I’ll make it worse than Spielberg! I’ll try to push all your buttons before you’re ready real hard.” But I’m not trying to do any of that perverse thing. It’s also part of the magic of comics, bringing these characters to life, seducing your reader into going on the trip. And you can have a different kind of audience for a different kind of trip. And I think I’ve tried to attract, or more typically, appeal to people that might be into modern art in the twentieth century and how it affected comics. But I’m still doing stories for humans, and one way to take people into a story... Well, like your movie did. Your movie, in a lot of ways, shouldn’t work. But it depends on very honorable, typical aspirations of humans relative to cooperation and the unlikely hero and those sort of things that still... There’s an emotional response from something that’s pretty formal. And in your movie, everything is extremely artificial. It’s telling you it’s artificial all the time, so in some ways it’s working like metafiction in the ’70s that I admire, in that the means of telling is being pointed at all the time, but if the story is powerful you’ll still go along with it.

I never really experience that feeling of forgetting that you’re reading a book. I always know that I’m reading something or know that I’m watching a movie, and comics is so artificial it gets that out of the way and moves on to, “Are you on board with this trip or not?”

Well, that’s one way to look at it. But I would think that it’s the confounding of that that would be interesting to me. Here’s something that’s totally artificial, but yet I’m gonna touch your heart or your intellect with it. But don’t you get carried away when you’re reading something? Maybe it’s harder in comics, but certainly it’s easy in movies to be carried away with a momentary cascade of emotion and forget. I dunno, I don’t know if I really forget, I’m more often confused when I get disconnects in media. [Laughs]

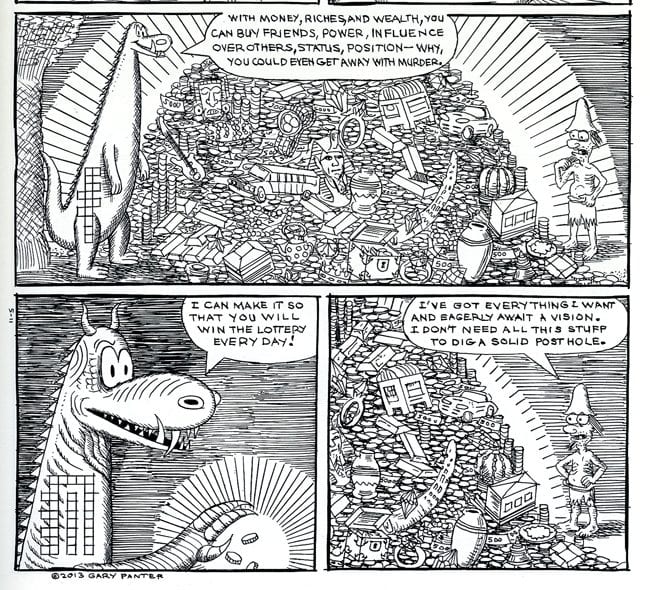

You operate often in this comic-booky world. In this new one, I thought, Songy’s offered all the wealth, he’s offered everything. And it’s so clearly a symbolic offering, this book isn’t going to paint a picture of having enough money to get by... He really has to choose between the material world and the spiritual world.

That’s really interesting. And actually making a book like this puts me in the position of hearing things like that and learning something, in a way. Because I hadn’t thought of that extremity as being essential to that narrative. That’s kind of true. It’s really about... Over and over, it’s the topic that I’m bringing to it, I guess Milton’s topic is really about righteousness and the will of God and that sort of stuff. And for me it’s more that this ignorant person can still be kind of honorable. I dunno, is he only accidentally honorable? Is he only honorable because he’s stupid, maybe? I’m not sure.

He looks like a funny animal comic crazy character, but I thought he was quite smart.

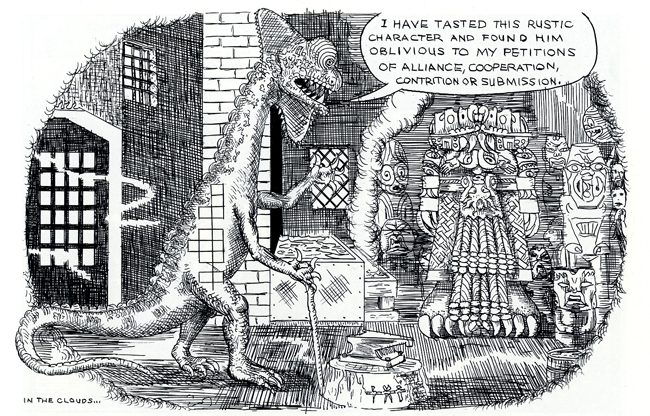

Well, he behaves very much like Jesus. And if you read Milton... We were both in that program in the Cullman Center [for Scholars and Writers], we got to read a lot of this material, and a thing that kept coming up in the analysis of Milton’s Paradise Regained is that there’s a conversation at cross purposes. It’s like they’re not even listening to each other or involved in the same conversation. Jesus is so resolute there’s no tempting him, and Satan refuses to hear it over and over and over and keeps coming back with another solicitation. It’s kind of an elaboration.

That sounds like your book.

Yeah, that’s my take. And I address that right towards the end. And I’m not an intellectual, you know, but to critique Milton it’s pretty easy to know that Milton’s going to try to impress you with yet another list. Like if he names rich cities, he’s gonna name them all. If he names a certain type of topography, he’s gonna name all he knows. And I don’t know if it’s like the cabinet of mind of a blind man, or that’s what he was always like—I don’t totally understand that. And he’s very self-serving. In the history of Milton, you see the evolution of his faith conforms to the evolution of his needs as a guy. At first, he’s virginal. Then he gets interested in women. Then it goes wrong; so then he divorces. Then it’s OK to divorce. And all those are like monumental arguments of the time. You could be murdered for hewing one way or the other on religious topics at that point, [which is a] really big part of the history of Christianity. And in that reading also was all of the history of Christianity wiping out sex, wiping out different versions of itself, the Adamites and so on. So it’s helpful for me that way to just look at Christianity more comprehensively as opposed to how I was raised.

So when you’re at the library—I’m curious... [Laughter] I know you told me this in person, but I forgot... What are these crossword puzzle-looking things on the people? [Laughs]

Oh, yeah. Well, I asked to see illuminated manuscripts from around the world, and one of the things that the librarians brought me was this Javanese manuscript painted on wood panels, and it was a wide lattice or something, and it folds up together—maybe with leather thongs or something—and on each one was a diagram, and often they were headed by a grotesque, which I use in this little crowd of demons at the beginning of the book and also of the back of our last record. Which were these demons, and they’re standing on these kind of crossword puzzle things. But they were actually good luck charts, and I think they’re maybe for betting or auspicious moments or just the way people use magic numbers at the horse track or something. But I really liked the structure of ’em, and that reminded me of the thing that slipped my mind a minute ago, which was that in the story, Henry’s out for a vision quest. And he has one through the whole story, because there’s no Satan. And Satan is typified by this pixel shape on him, because he’s going to keep changing throughout, and I wanted it to be easy for the reader to have something that ties all the different versions of this ever-changing character together. So, anyway, he’s having this vision the whole time of Satan, and then at the last sentence he kind of acknowledges it for a second, like, “Oh, yeah, Satan appeared to me. I did have a vision.” But he’s drunken at that point.

When you gave your presentation at the library, did you have a few key books that you showed side by side, or were you one of those people who had a hundred books checked out?

No. I kept a sketchbook of all the books I read and drew pictures of them and made little notes—very minimal notes just to remember what I’d done. And so my presentation was about a view of Christianity, and in a way it was framed by the enlargement of what I was taught as a Christian, and then if you thread it past these various things that I learned at the library, I tried to do a historical survey of like... And I went through the whole thing that I did with the other two Dante books. Y’know, it’s like Dante, Boccaccio, Chaucer, and this lineage—Milton, Joyce, and so on. But it’s also [Emanuel] Swedenborg. Luc Sante was in that group I was in, and he suggested that I read Heaven and Hell by Swedenborg, which was very interesting, because it was like someone like Blake, who experienced angels taking them to heaven and explaining the whole situation to them in his vision quest. And this was that people didn’t know they were dead, because they still had jobs, and they had to go buy clothes and stuff, and they were real surprised that the afterlife was so much like Earth. And it turned out in his philosophy that people just kind of gravitated toward heaven or hell. If you were like bad smells and loud people and obnoxious stuff, you would drift off to hell, and if you were really pious or something, you would hang out with the pious people. And I talked about Blake. So it’s really like “Visions of Christianity” and then “Enforcements of Christianity.” But it’s a vast topic, and I’m pretty simple.

In the presentation, did you even show your drawings in your book, or was it all notes?

I think it was mostly notes, really. I might’ve brought my pages in, I can’t really remember. It was so terrifying to do that presentation in front of a crowd of really smart people. And it’s like, “Oh, I’m the dope in here.” People liked my presentation for some reason, and I think it’s probably that I had this background of being somewhat raised to be a preacher, so I was sort of forced into public speaking. And then I became a teacher. When you’re a teacher, it’s like a TV show every week, so you’re not so frightened. My hands might shake, but I can talk.

This book doesn’t feel like it needs footnotes the way some of your books have. I just read it straight as a story. I thought, “Oh, this’ll be great interviewing Gary about this book, because I won’t have to do any research!” [Panter laughs]

Yeah, there’s tons of research underneath it, but you don’t have to have it to get the book. And really, it’s because the story of Jesus being tempted by Satan—I don’t know how many verses, five or six verses in the Bible—and Milton just lards it with words and allusions and his philosophy. And so it’s hyperinflated, but the story’s simple. One of my friends, John Wray, who was also in the Cullman Center, he asked me why I stopped using multiple panels the farther I went. But the farther I went, there was less said, you were just hashing over the same things in different categories, and they weren’t worth turning into comics in a way. I start realizing, “Well, Milton’s using all these words to say something that’s just two sentences often.”

Right, right. Yeah, I understand.

Oh, can I say one thing. I still interspersed a reading of Dante with this. I did the same thing as the other books formally, somewhat, in that I broke the pages down according to the same books and visions of Milton pretty much, divided among the 33 pages. And I still read Dante for lighting effects. So I didn’t address Paradise by Dante directly, but the lighting gets lighter or darker according to Dante or more stars or eagles appear, that sort of thing.

The lighting meaning the darks on the page?

As you’re going through, like on the first few pages when finally the Babylonian God appears, and there’s a moon in that panel. And that place in Dante’s Paradise is when the moon appears. And then as you go through, rings of stars or interlocking rings of stars or birds or the eagle appears... There are these big symbols that appear in Dante’s Paradise that are the stagecraft of the book, a hidden set of tiers. It’s not important, you don’t have to know about it, but that’s just how I did the book.

I'd see you working on pages and you wouldn’t know what sections of the page would be. It was open to improvisations in areas of the page, it wasn’t all completely locked down four years ago when you started.

No, because I just did it page by page. I knew how much information I had to parse in that number of pages, and I decided the format based on Dante’s Cantos years ago, but I kind of just worked on the page I was at, and then I would read the next book and address the place... Early on, those books are short, of course. I think there are four books and Milton’s Paradise Regained. So wherever I was, I addressed where the characters were and what they were doing and what they were saying at that point in Milton’s poem.

One time, I can’t remember how you said it, but it’s always stuck with me. I was at your place and you were telling me about your beaded necklaces or something that you were working on, and you had all these different, experimental, non-commercial projects-- projects that might not have any audience-- and you said that being raised Christian helped you follow all these unusual ideas, because you always had the impression that you were being watched.

Yeah, I’m not sure about the first half, if it propels me, but I do have the feeling of being watched. I was thinking about that today, it’s odd. We were taught that there’d be the Day of Judgment, it’d all play back. And it would be really fucking embarrassing, you know? [Shaw laughs]

[Jokingly] Why did he spend all this time drawing comics?!

Well, I dunno, you just decide what you’re good at, what fascinates you, and you kind of go for it. I don’t really have giant resources, I’m limited in a lot of ways, so I can do these... Like if I take up lanyards, which I have as part of my little projects—lanyard making, like you made at summer camp, those woven plastic gimp things. When I learned how to do that—I’m completely untalented at it, but I can invent my version of it, I can get as far as I can get. It’s the same with my candles, my comics, my paintings, my music—everything. I’m working within my limitations. So if you’re working within your limitations, you can actually get stuff done.

When I saw the drone in this comic, I thought, “I wonder if Gary pictures this being what’s looking over him-- a drone.” But it sounds like it’s more of a human person watching over you.

It’s a question, the whole question of, “If there were a God, what would it be?” Or “If it is, what is it?” That’s what all this Milton stuff is about. The fear of death, first off, the unknown of death, and then having some wish to have a happy ending or be ongoing or whatever. And then there is a nature of things, which is to begin and end over and over. There’s what we learn from science about existence. So no, I’m not a total Pollyanna, and I’m certainly not a nihilistic person. I think it would be too crushing if I was just thinking, “Uh, there’s not any possibility of anything, the colors don’t mean anything.” But if I can bring some meaning to them and be able to function, because there’s also just being completely destroyed by your fears. I can go there, I can get completely existentially wigged out—it’s not pleasant.

Doesn't that happen in the middle of the day, every day? [Panter laughs]

It happens at different times. In the middle of the night, it can happen right after I wake up. It’s just letting your mind go there, or you’re just at the point in your personal cycle of sensitivity or insensitivity where you go there. Your own rhythms. This art stuff is kind of about trying to know yourself better by having a real... I think I said it before. You grow your antennas out like a snail, and then you sand them down a little bit so they’re extra sensitive and trust that it will lead you somewhere. I find that there’s all kinds of odd psychic things that happen that I don’t dwell on, and there’s all that kind of insanity.

Well, you worked on this book at the library, how did it change being... I don’t know, maybe your first comic where you had it as a job, and you had an office and had to go there every weekday and work on your comic? How did that change your...

My whole career has been stealing time in the middle of the night after I’ve done the horrible illustration or freaking out about money and stuff, and so it was great. It was just amazing to be paid to go read books and draw. But you’re still subject to your rhythms. So I can’t go and just sit down and start drawing. I have to wait for the moment I can draw. So I spend a lot of time reading and sometimes snoozing and walking around. But it was the ultimate luxury. It meant that I could slow down the drawing. Because in some ways, drawing comics, these kind of long-form things, either a long comic or one that takes a long time to do, there’s also just the fear of dropping dead in the middle of it. So you want to finish it. So there’s an instinct to rush, but since I was being paid and had this year that I was committed to, it allowed me to go, “OK, I’m gonna really slow down on the cross-hatching now.”

Do you feel like it came with a responsibility to do something on the same level as the other Fellows there?

Yeah, I think there’s always... It wasn’t just because of the Cullman Center, certainly there’s professional pride or being able to deliver, being a functional human. But always I think as an artist one is trying to be better and more interesting or as interesting as before. Unfortunately, a lot of artists—and I think me included—have certain epiphanies early on that are very strong that come from avid pursuit and interest and new brain and stuff, and so you can sometimes make these leaps that are never gonna be made again. So making art has to become a different kind of delivery.

You mean that unfortunately those leaps happen more when you’re younger, is that what you’re saying?

Often they do, yeah. Not always, but often they do. Like say, Jim Nutt. I love all of Jim Nutt’s work, but his earliest stuff when he’s really under the influence of [Karl] Wirsum or whatever it was, it’s super powerful stuff. And he would make a real different kind of work after that, which had more dignity and pace and so on. But it would never blow your brains out again like that.

Do you think of your comics existing in the comics landscape, or you don’t really care?

I’m aware of it, yeah. There’s a lot of parts of it, but one part of what I’m doing is paying a debt to Forrest J. Ackerman and Ed Roth, Claes Oldenburg and people like that, people that blew my mind, and it’s a long list of people. But trying to do that sort of thing where you make these emotional or psychic triggers that when young people of a certain trapped kind of variety come across, it’s the key to escaping their cage.

This popped into my head earlier today. You were inspired by the ’60s comics, but when we think of those underground comics, we think of so much sex and violence and social issues—like Fritz the Cat is all about race relations—but your comics, especially now, don’t have any of those things in it. Am I wrong?

No, I think you’re right. I’m trying to do a hippie comic, it’s part of my giant, miniature hippie project. I’m doing an ode to Zap comics or hippie comics. And so the first eight pages, I just drew them real quick, because it was basically being back in high school trying to be like the part of that stuff I admired. And then as I’m doing it, I’m realizing, “Whoa, what is missing out of this?” I don’t know what I have to bring to it, because again it’ll be like a 32-page comic, and so it’ll be like—sorry, I’m saying like a lot—it’ll be four eight-page stories. And so I can continue along the line of the first one, which is, I’m just going to imitate [Victor] Moscoso and Rick Griffin and Martin Sharp and pile all their conventions together and explore that. And that’s a vast territory, really. Definitely, I could do a comic based on that. And then when I look at comics, they really have stories, and a lot of ’em are just shit. A lot of the stories just suck.

When you look at those psychedelic comics?

Yeah, I mean especially the third-rate ones. To me I perceive several generations of underground comix. There are the Zap guys, which are like [Gilbert] Shelton, [Rick] Griffin, [S. Clay] Wilson—the Zap people. And then the other group seems to be a few years younger, maybe only three years younger, and that’s [Art] Spiegelman and [Bill] Griffith and Skip Williamson. But then there are people like [Jack] Jackson that are probably from that first generation. So I kind of divide them up. But then suddenly there are these anthologies—Yellow Dog—which goes on and on. Every aspiring artist or hippie who was psychoactived is trying to draw a comic, and a lot of them are very much clichés about the man or the corporate takeover, and Jimbo’s a part of that. He’s in a corporate world, a dystopia. There are a lot of those kind of comics that are pretty lame. I think there’s some good stuff. Then there’s stuff like [Richard] Corben that’s not even part of underground comix, he’s just stuck in there. He’s like the sci-fi fantasy world to come from the ‘70s or something. So I’m thinking about it, but I’m wondering... Because the comics I’m doing now, I am doing comics with characters like Fritz the Cat. They go places, they do things together, they interact, there are consequences. And so I’m wondering if I can bring something like that to a bunch of stoner characters that are wandering through this kind of psychedelic landscape. So I’m just trying to puzzle it out. And then I think I can do it stylistically, where I suddenly switch to putting as much black as Moscoso and Skip Williamson put in their comics or something. That would be enough, almost. So anyway, I don’t know. I just overthink this stuff, and that’s my job.

Are each of these little side characters in the Songy universe having their own spinoff comic?

Well, that’s the next Jimbo. The minicomics I've been doing adds up to the next Jimbo book. It’d be 80 pages long and collect those minicomics. I don’t know if I have to redraw some of the first ones, I don’t know. And then I have to do another 30-page Jimbo science fiction story, I guess. Or, because I’ve done things with the other characters, and I could follow the other characters more, but I think I owe it to Jimbo fans—if there are any—to do another Jimbo sci-fi story of some sort. My obsessions stay the same, so I end up revisiting them. You look at Dan Clowes kind of refining that story he’s telling, and I think that’s a natural thing that happens. Do you find yourself revising the same structure or story in a different way each time now?

I don’t go back and look at things, but often someone will tell me, “Oh, you did this before.”

I don’t either, but I think it’s just a thing that it’s a part of your makeup. You’re working on these knots, and the knots might become different...

This Songy book felt new to me.

Oh, that’s cool.

I wouldn’t say it’s a "step forward", because I really loved the other books, too, but it just seemed completely new and different.

Well, that’s ideal. My ideal goal would be to not be old and stale.

I don’t think you have to worry about that.

Oh, good. [Laughs]