When Meisel had begun writing about comics, there were those who objected he knew nothing about them. This objection was not entirely unfounded; and while he had filled in some gaps in his knowledge, another generation or two of cartoonists had come along with whom he had not kept up, so, proportionately, 30-years down the road, he probably knew less.

Still, when a Croatian woman contacted him because of their shared “love” of comics and offered to send him samples of her work, he did not explain that he did not apply the word “love” much beyond what he had – and still – felt for his deceased wife, or that he barely read any comics. He said, “Sure.”

He was 77, three-years a widower, the survivor of a subsequent heart attack so severe that he marveled daily with tempered bemusement at the persistence of his continued presence. He had no idea how long this feeling – or, for that matter, he – would last, which made it all the more an object of wonder. Each morning he sat in a café, facing a window beyond which people passed, performers in a play whose plot he would never divine, and added words to his current creation. Besides the gratifying chemicals each perfected sentence triggered in his brain, he enjoyed the surprises his writing, fate and – in this case – international postal services brought him. One day he might hear someone had found his insights so meaningful as to surpass anything their reader had previously encountered. The next his prose had been found so “bizarre” “as to be the product of either “a bad batch of peyote” or an “LSD addled brain.” Now a book he had written a decade earlier had so affected an artist in Buffalo that she had connected him to an artist in Serbia who had connected him to this new fan 6000-miles away.

i.

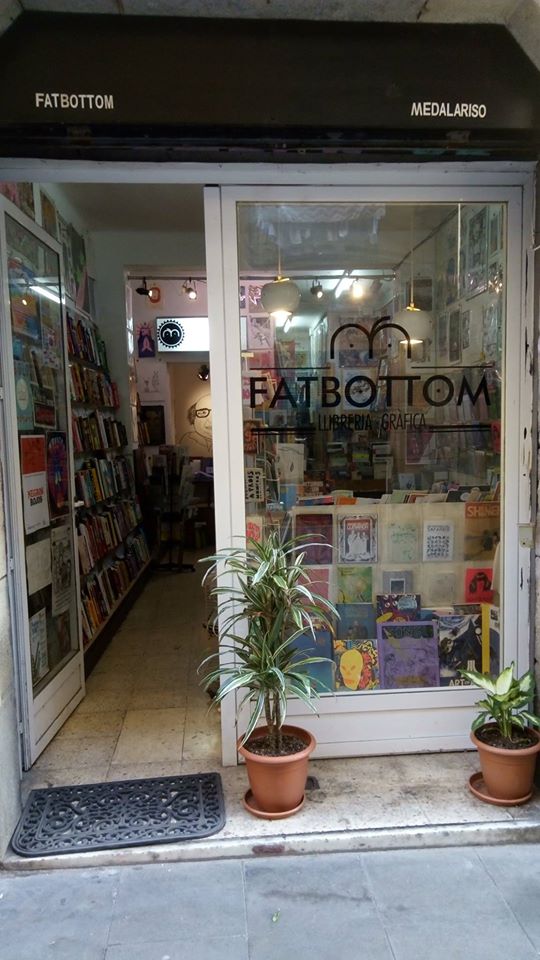

Ivania Armanini had been born in 1970. Following graduation from Zagreb’s Academy of Fine Arts, she spent several years exhibiting paintings, solo or in groups. Then a friend introduced her to alternative comics.

A century’s exposure had taught Croatians to regard comics as fare for kids and dunces. But the possibilities for blending the visual with the literary intrigued Armanini. While freelancing (posters, flyers, booklets, CDs), teaching (elementary, high school, privately), performing restorations (churches, chapels, altars), and hanging at Zagreb’s only punk club, she explored ways to deliver “anarcho-cultural” messaging through comics.

In 2002, Armanini founded Komikaze, an organization which would produce, promote and distribute comics that expressed “universal human values,” without being limited to “a narrative form in a realistic mode of expression.” She wanted comics infused with elements of street art, action painting, expressionism, abstraction, aspects of film, literature, and music. She sought the experimental, playful, humorous, not the craft-oriented, academic, or mannered.

Komikaze hosted a web site where creators displayed their work and exchanged information and ideas. It published this work on the internet, in ‘zines and an in-print anthology. It launched Femicomix to support female members. It participated in workshops and festivals, “because,” said Armanini, “they... [connect] underground places, groups and productions, ...forming a no-borders contemporary art network... which is ideal for nomad people.” These nomads came to include about 300 artists in 55 countries.

Armanini sent Meisel a Komikaze anthology, three of her own mini-comix, a collection of her shorter works, and a book on which she had collaborated. He read them once, twice, returned to spots a third or fourth time. He took his notes and set down his thoughts. Passers-by who observed the comics on his café table registered admiration or snorted with disdain.

ii.

In writing about comics, Meisel had formulated a set of beliefs – or prejudices – which he sometimes thought he should post on his writings, like warnings on cigarette packs. One was that anthologies were of little interest.

Komikaze, Armanini’s, did not dissuade him from his belief. It contained work by 23 contributors in English with a Croatian translation (or vice-versa). This work depicted aberrational behavior of the sexual, violent, and bodily function persuasions. It opposed fascism and expressed depression. You did not have to have read many alternative comics to be familiar with these concerns. And if you had this familiarity, an anthology was a poor place to re-encounter them, since no individual had the space to probe them in depth or with sustained originality.

But as Meisel considered his dismissal, it wobbled like his espresso when he kicked his table’s leg. Certainly, in the U.S. most taboos had been so shredded he sometimes wondered which it would take courage for a cartoonist to defy. Sometimes he thought they would have to challenge those erected by the left; and when he saw where that might lead, he felt his grasp on First Amendment absolutism weaken. Look at the shitstorm Robert Crumb had caused. Give that freedom to someone who wasn’t kidding; multiply it by thousands; let their readers vote; and what do you get? The bleeding hemorrhoid occupying the White House. If websites could design ways to weed out robots, why couldn’t they weed out dickheads?

Anyway, sitting comfortably in a Berkeley café, what did he know about courage? At minimum, if you wanted to sample artists from Serbia, Croatia, Macedonia, “Komikaze” was a good place to begin. And some of the visuals – Damir Stojnic’s black or white forms struggling for recognition through disfiguring whites and blacks, Iva Artoski’s meticulously rendered insects overseeing human obliteration, Bambi Kramer’s color-washed, bulbous monstrosities – kicked him in both eyes. But did he have the time to track down more of their work? To learn about their influences and aims? His days were limited. His brain full. Was he not better served by developing what was already there than piling more upon it?[1]

iii.

Meisel’s most fervent preju-belief – and the one in which he had the least confidence – was that comics should be judged by their words.

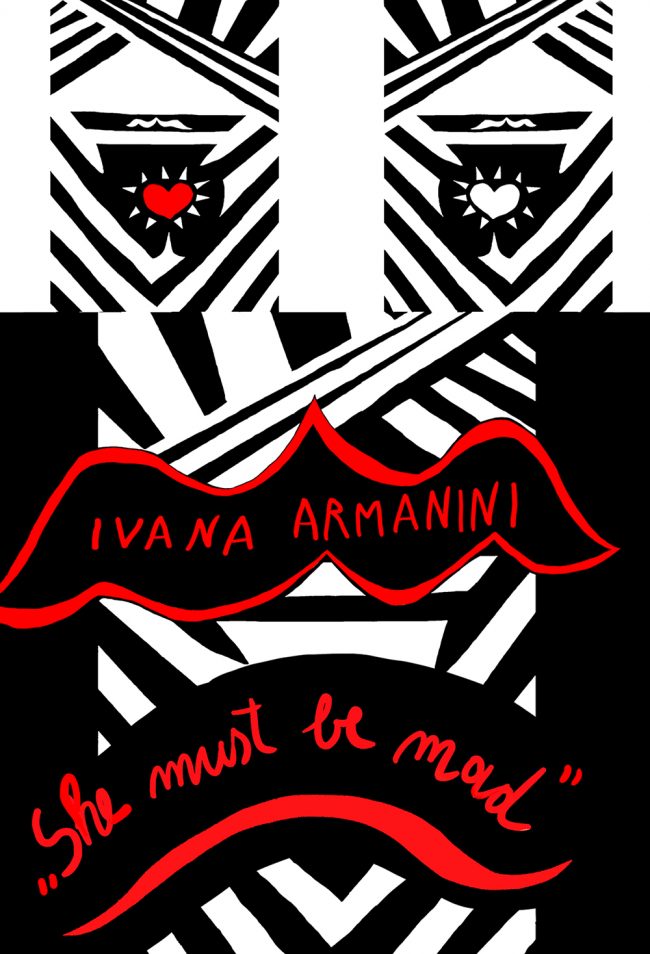

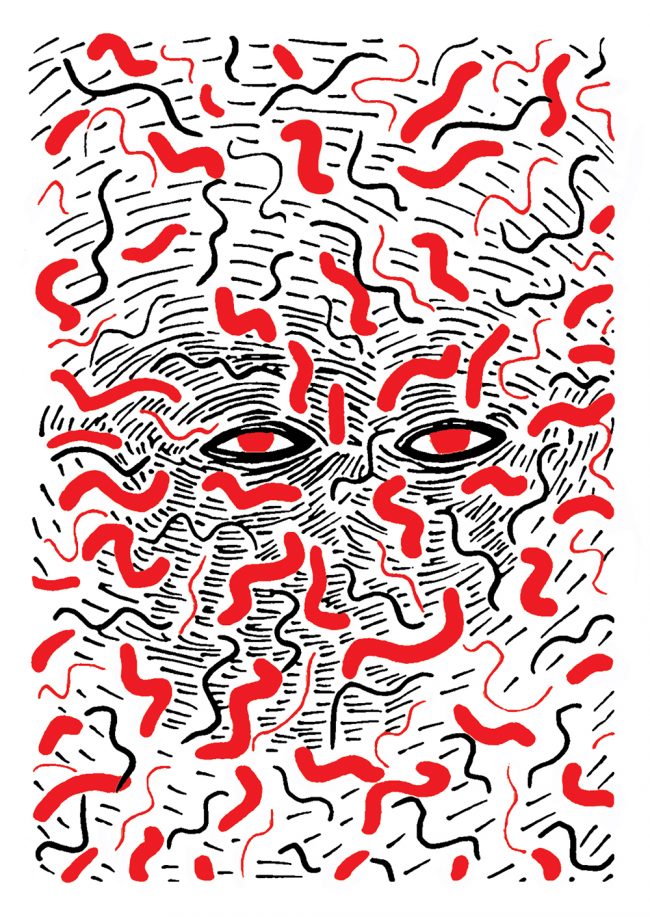

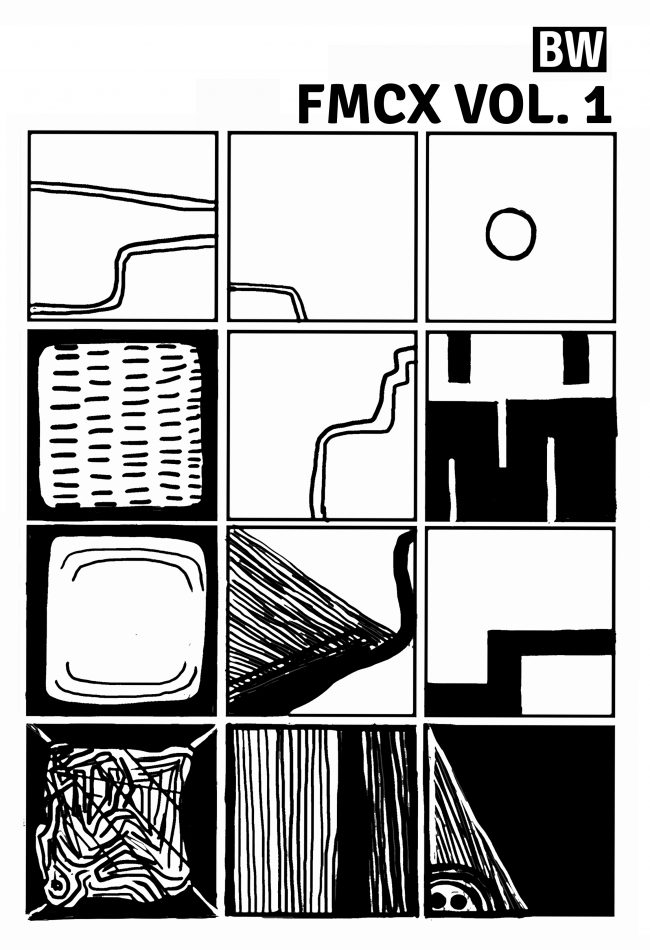

One of Armanini’s mini-comics[2] had none. The others might display a “BOOM” or “AH HA”, but word balloons were rare and conversation non-existent. Occasionally, a message reached Meisel. (He got it when Donald Trump’s head exploded due to a build-up of swastikas within. If only!) But more often he struggled to determine Armanini’s intent. She had abolished not only words but often the identifiable, as if seeking to capture thoughts/ experiences/ sensations particular to herself. Meisel had sensed comics aspiring to become museum-worthy objects d’arte, no more verbal than Etruscan vases. Armanini’s elimination of language, her pages emptying of all but design, even her heavy paper stock seemed steps in this direction.

He admired this movement. Why should it matter if a vision was rendered on paper instead of canvas? If measured in square inches, not square feet? If broken into panels on pages, not frames across walls? But wasn’t this contrary to the comic spirit? (Something in him still thought they ought to cost a dime.) Weren’t comics supposed to be accessible to the masses? Armanini’s minis might reward those willing to linger over them and ponder, but that seemed suited for an intellectual elite, not the all-in-color mob. He ran an index finger around the rim of his cup. Then again, must a story have “meaning”? He recalled the reply of the Language Poet whose work had caused him similar puzzlement, “What does ‘meaning’ even mean?”

The minis seemed part of a world that was increasingly not his. Every week brought magazine articles he felt no need to read. Profiles of celebrity chefs. Analyses of whether gaming was an addiction. Ruminations on the impact of facial recognition software. Memories of high school football games and girls he regretted not having dated intruded more often into his morning meditations. He felt himself aging out of the everyday. The window separated him from more and more. If asked his opinions of Super Bowls or congressional inquiries or presidential primaries, he shrugged. Something would happen, or something else would. In some societies, his age would have qualified him as a Wise Man whose counsel was revered. Others would be tailoring an ice floe for him.

The minis sat before Meisel like mysteries waiting, clue-by-clue, to be peeled away and solved.

iv.

Then there was the whole darkness/transgression thing. Once Meisel had been the guy, if you had written a shocking book, to whom you sent it. But now his embrace of outrage felt slack, his eye peering elsewhere, over its shoulder.

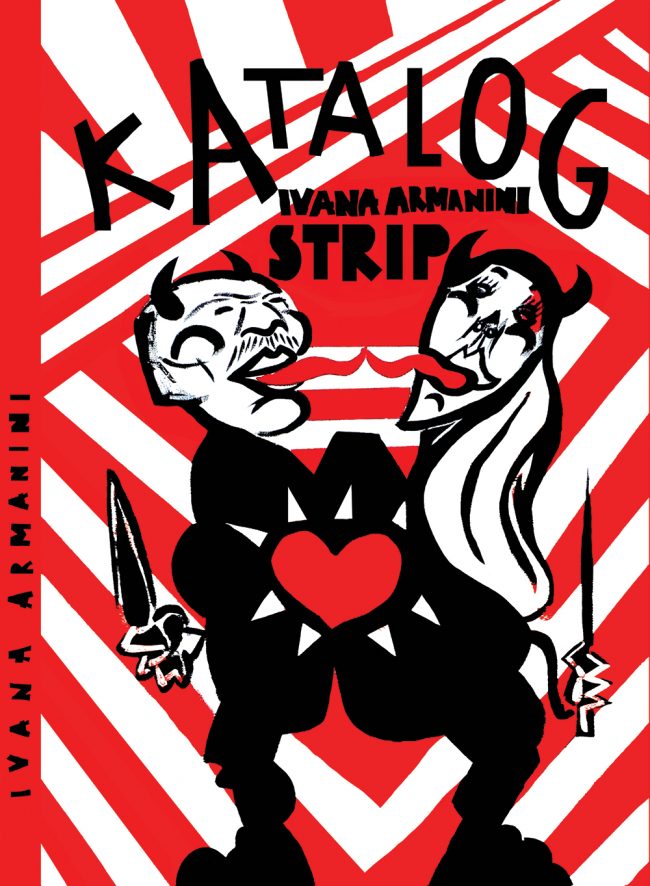

In “Katalog,” Armanini’s collection of 52 stories (2000 - 2015), full-pagers exploded like posters slapped on walls amidst tear gas and hurled bricks. Single panels stung like childish grotesques. A cartoonist’s line had rarely seemed as club-like. Black had rarely menaced so much or white glistened as icily. The stories consistently condemned. Evil gripped mankind. People labored in misery. Blood would shortly boil.

The centerpiece was a graphic adaptation of “The Adventures of Gloria Scott” by the Croatian LGQBT activist Mima Simic.[3] Some panels had word balloons; in others words ran helter-skelter, hither-and-yon. Some were in Croatian, some English. Gloria might appear potato-like, an assemblage of geometric figures, entirely head, entirely teeth, a tribal mask, or Valentine heart.[4] Copy-editing had not been prioritized. Characters got “tiskled” not “tickled,” had “fardrums” not “eardrums,” experienced “contem” not “contempt.” Misguided line-breaks resulted in “neare st,” “whi ch,” and “o ffered.” Chaos was the feel, absurdity the guiding principle.

Scott is a London-based detective. Her assistant, Mary, recounts their adventures in Great Britain, Barcelona, Prague, a section of Dalmatia populated by cannibalistic Native Americans. Characters include an armless Bill Clinton, a Dorothea Lang (sic), daughter to Fritz, Samuel Johnson with good friend James Boswell, Miranda Richardson, Martha Reeves, and Harry Palmer, none of whom correspond to their better known counterparts. Characters are beset by missed periods, heroin addiction, binge eating, constipation, attacks of howling, impregnation by gigolos, necrophilia, and strokes. They are decapitated, raped, stabbed, poisoned, aborted by “primitive vacuum,” have organs extracted, commit suicide and matricide, are mauled by dogs, and murdered by gas and building demolition. Some crimes are solved which the text seems not to mention. Some characters are put to death without explanation. Some are slain for crimes they did not commit. Sometimes by Gloria and Mary. (We didn’t like him anyway, Mary explains.)

Meisel had written darkness himself. He had read Celine. He had seen Parasite. He had turned from the page in the newspaper where the European Union was selling out to agricultural barons, to the page where a Nobel Peace Prize winner was shilling for genocidal generals, to the page where the head of the Mexican national police was revealed in the pay of a drug cartel. He knew Brazil and Australia were burning and plastic was choking the whales, and he could consider COVID-19 to be the planet’s defense against the ravages of man. But his climb from the pits into which his wife’s passing and his own illness had flung him had left him believing living in light preferable to living in darkness. Worry, instruct the Buddhists, is a projection into a future which does not exist. Only the moment is real, and, in it, most often, we are fine.

He wondered if Armanini’s darkness stemmed from her personal life or the geo-political situation in which she had grown. He wondered what business he had expressing opinions about the mindset of a woman in the Balkans. (Who did he think he was, Rebecca West?) Another newspaper story intruded. A pitch by a celebrated novelist for a TV movie about a fire which killed 36 party-goers in an Oakland warehouse, home to numerous independent artists, had been green-lit. The story’s author, a friend of many of the victims, believed it “unjust” for someone “disconnected from the DIY arts scene... to profit from telling (this) story.” He especially objected that the script centered on the hapless young man who had been second-in-command at the warehouse instead of income inequality, the lack of adequate housing for struggling artists, and the “depth” of the deceased. Their families’ and loved ones’ feelings should be paramount, he wrote. “We must keep considering these thorny issues of narration and control.”

“Write your own script!” Meisel had wanted to scream, issues of narrative control having been as absent from his development as video games from his bedroom. His playwriting teacher had encouraged, “Shakespeare was neither a king nor a woman.” Now Shakespeare was just another old white guy, and white guys were to be ignored because, as another fellow at the café had remarked – in his case dissing Dostoyevsky — because “Look of the shape they’ve left the world in.”

Writers seemed to be herded into lanes which narrowed daily. Should he only write about 70-something, middle-class, white, non-believing Jewish guys? Did his DMV-issued handicapped parking placard certify him to speak for the disabled?

v.

Finally, Meisel had long believed comics poor vehicles for “realism,” whether history, politics, biography, or memoir. Their “unreal” pictures betrayed them. (Let people “see” on their own, he thought.) Pure prose allowed more information, encouraged nuance, deepened thought. But sometimes a creator’s imagination transported a comic somewhere special.

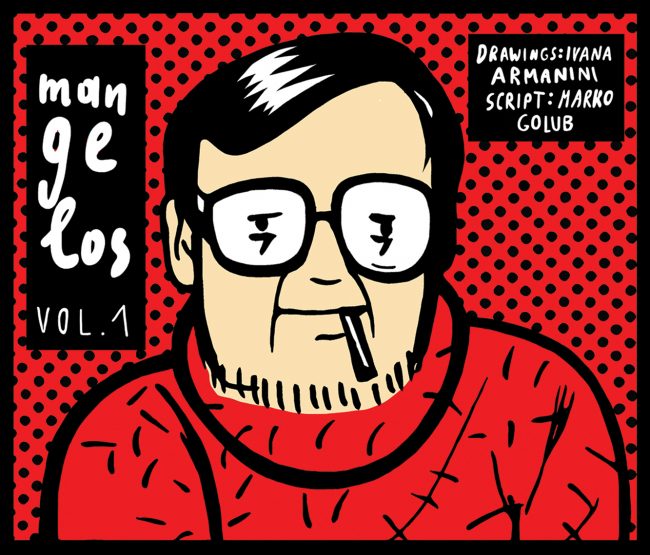

Mangelos Vol. 1, a whimsical, quirky, brainy study of the artist/philosopher Dimitrije Basicevic (1921-97), with drawings by Armanini and text by Marko Golub, was genius. It ushered Meisel into unknown worlds. It enhanced his understanding of his own. Armanini termed the book, not a “conventional” biography, but “a dialogue.... accepting all [Mangelos’s] contradictions and recreating an authentic imaginary universe from his fragments.” Cool.

Basicevic had been born in Sid, then part of Yugoslavia, now part of Serbia. His family had been farmers, his father also an artist; and Basicevic received a PhD in art history in 1957. His critical writing and work as a museum curator and gallery director encouraged the development of abstract art in Eastern Europe and championed outsider artists. In 1959, he became a founder of the avant guard Gorgone Group. Taking the name “Mangelos” (a town near Sid), he exhibited works he had kept private for 20-years: notebooks, tablets, globes, on which he’d inscribed letters, words, sentences in Latin, Gothic, Greek, Slavonic, Cyrillic, Glagolitic, and Runes. “Writing a painting, painting literature,” he called it. “Negating a picture, creating it from words; negating a word by painting it.”

Mangelos Vol. 1 was divided into “Manifesto of Manitestos,” “The SHID Theory,” “Tabula Rasa,” and “Non (The Battle for Nobleness).”

“Manifesto” declared that civilization has reached a point which, for artists, means that thinking has become “based on the principles of social functionality... instead of emotionally structured units...” In “SHID,” a heavy-sweatered, eye-glassed, cigarette-smoking Mangelos, the personification of an avuncular, Middle-European intellectual, posits that those who speak of “three Van Goghs” or “several Picassos” are justified because human cells renew themselves every seven years – and that, by this token, there “should be nine-and-a-half Mangelos.” In “Tabula,” Mangelos tells an interviewer that, between 1935 and 1942, he commemorated deaths of people he knew with black rectangles drawn in notebooks, thereby launching his “struggle with something that can be called art.” In “Nobleness,” someone/thing named “Non” is exhausted by a battle (perhaps, but not necessarily, that “for Nobleness”). Van Gogh (Huh?) takes cloth animals from a bag. They come alive. When they look at Non, he becomes “noble and good.”

Meisel was nothing if not puzzled. Outside the café, a street-sweeping truck cleared the gutter of trash. Inside the grinder reduced coffee beans to dust. What did it mean for art to be based on “social functionality”? (It didn’t sound good.) What was the significance of any person above the age of seven having multiple selves? Why was “art” italicized? (It seemed sarcastic, like “art,” whatever it was, was overrated.) How did a look from a come-alive cloth animal make anyone/thing “noble and good,” and how was that useful for the rest of us? Mangelos, Meisel decided, had to be kidding – and kidding in the service of a greater good, which, for the moment, eluded him.

“

Manifesto”’s visual art was primarily globes against blackness or planets against an equally black cosmos. Sometimes numbers or snatches from the text in French sat upon them. At the end was a planet with the numbers 10 to 1 across it, while outside, in the blackness, the same numbers, larger, repeated in reverse order. “SHID”’s visual representations of Mangelos became obscured, page-by-page by replicating, darkening dots, until he vanished and the orbs devolved into what-could-be the cells whose renewal created one anew. Nine brief chapters followed, each detailing a period of Mangelos’s life, the title of each presented as if on a movie or TV screen, until the later years when the titles slip off the screen and are replaced by blankness or lines zig-zagging darkening toward blackness also.

Mangelos’s “struggle” with “art” (or “art”) had landed between Meisel’s espresso and the wrapper from his energy bar. If “Mangelos Vol. 1" had been a mystery, several corpses had been found and everyone had gone to lunch. If a romance, many eyes had met and all parties had turned separate corners. The blackness – the recurring blackness – brought back to Meisel the rectangles obliterating the names of the dead in the notebooks of Mangelos’s youth. In light of the blackness – blackness then, blackness now, blackness forthcoming – a kidding response seemed as good as any. The idea of multiple lives appealed. Meisel could count several, with the one holding sway since his surgery unlike any that had preceded it.

A backpack sat on the floor. Glossy black leather. Variously sized zippered pockets. Sturdy, well-cushioned straps. No one was at the closest table. Nothing indicated anyone was returning. The restroom key hung on the wall, so no one was there.

When the evening news did not report the café had ended with a bang, Meisel decided to return in the morning.

[1]. Meisel felt more sheepish when, while his piece was in progress, “Komikaze” received the 2020 Alternative Comics Award from the Angouleme Festival, besting 36 other entries.

[2].In the order referenced, these are “She Must Be Mad,” “FMCX,” and “Nini Zine.”

[3]. Armanini’s adaptation had originally been published in 2005 by a leading Croatian publisher. (It had taken her five years to create and earned her about $500.) Now she had added episodes, “refined” the graphics, and made it “more readable.”

[4]. Here is Armanini speaking for herself about her art: “I was fascinated by the grotesque atmosphere of Simic’s stories, but my storytelling is quite different than the original. What interested me and what I draw are moods and atmosphere. I dismissed many of the narratives in the name of dark compositions and expressive drawings. The characters have no recognizable faces; London... is not even indicated. The text is sometimes subordinated to contrasting black and white surfaces. The figurative side of the drawing comes down to impersonal symbolic representation. If Gloria is furious, there will be sharp, contrasting edges of black and white surfaces that fly like knives. If she is lazily resting, I will draw her in a few lazy strokes. I did not aspire to repeat the story but to convey my intimate reading experience. There are many abstract and expressionistic additions to the story and there are signifiers for things from my experience that link to the text to create a new reading experience. What matters is how I communicate my experiences: the character of the line; the amount of grey tones; the appearance of the letters; the choice of rounder or sharper shapes.”

Ed Note: For more information about Komikaze and Ivana Armanini's work, their website is here.