To mark the release of Chris Ware’s decade-in-the-making Building Stories—a box of fourteen print artifacts ranging from cloth-bound volumes and newspapers to broadsheets and silent flip books—The Comics Journal is featuring a series of essays from the contributors to the 2010 volume The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking (University Press of Mississippi). Each contributor is revisiting the argument they made in that edited collection two years ago in light of the newly released work, speaking to the ways in which Ware’s comics have either transformed in that time or are returning to the themes of his earlier publications. We hope these first thoughts give rise to a spirited discussion about a novel that will shape conversation in the medium in the years to come.

The panels that make up a comics text are, above all else, units of time, diagramming moments of varying length and precision. A given page, then, must be understood as a space in which various images of various presents jangle up against one another, such that where the panel is a unit of time, the page is usually a unit of history itself. In conventional comics narrative, past and present linger on the limits of every frame, a capacity that literally makes temporal relationships visible. This tendency has proven a powerful tool for historical meditations of various kinds, not least of all those that take up the history of the medium itself. Cartoonists like Dylan Horrocks and Nicolas de Crecy, for example, routinely juxtapose otherwise discrete moments in the history of art and comics to imagine alternate trajectories for and of the medium. More generally, there is hardly a comics text worthy of consideration that does not ask important questions about where the form has been and where it is going.

As I argued in “Masked Fathers,” my contribution to The Comics of Chris Ware, Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan embodies such an ethos. In Jimmy Corrigan, Ware overlays the figure of the father with that of the superhero, allowing him to grapple with the ways that superheroes have long shaped public perception of the comics medium. Ultimately, the novel finds no real solutions to this dilemma, but neither does it wallow in its failure. Instead, Ware employs a variety of formal strategies that enable his book to tentatively visualize the possibility of historical difference. Thus, for example, one sequence late in the novel finds a character presenting the protagonist with a series of photographs of her past. As she selectively arranges them, they fill up the entirety of Ware’s panels, suggesting that comics might become a medium in which we pick and choose our history rather than allowing it to be thrust upon us.

Against the background of Ware’s discontent with the dominance of superhero narrative, such instances of formal play might well be read as attempts to rewrite the medium’s history in spite of the inescapable pressure of its genre-bound past. The novel displays a palpable longing that the past might be different, but it also demonstrates a resigned comfort with the inevitable collapse of every attempt to change that which came before. We find ourselves in a climate in which the past weighs so heavily on the present that any progress into the future comes only with great effort. For all of Jimmy Corrigan’s formal innovations, the text as a whole suggests that any desire for true maturation will remain blocked, barred, or otherwise prohibited. The revelatory family tree that arrives near the novel’s conclusion testifies to this very fact: History is what has been, the accumulation of links and bonds that could not be otherwise. At best, we can only hope to find lost treasures in its darkened corners.

With this sense of historical determinacy in the background, Building Stories turns from problems of the collective past to questions of personal memory. In one of the text’s most virtuosic sequences, Ware presents a cross-section of the ostensibly titular building, overlaying it with a catalogue of events and experiences that took place therein over the past century, along with the objects that filled it up: “296 birthday parties,” “68,418 orgasms,” “61 broken dinner plates,” and so on. This record of prior feelings, frustrations, and occasional pleasures, is notable first for the way that it detaches them from particular bodies. While Ware positions the accumulated orgasms, for example, over the female narrator, she sits placidly upright in bed, reading by herself. In their enormous numerical excess, these items outstrip the scope of any one individual form, indeed of any one life. While Ware letters this sequence with the same delicate cursive script he used when investigating Jimmy’s paternal past in his earlier novel, he pointedly detaches these terms from any single historical trajectory. What we find here, then, is something like a sedimented record of all those everyday banalities that must go forgotten if we are to continue going about our lives. Like the apartment building itself, which disappears into the weave of the text as a whole, these are the things we leave behind as we mature. Indeed, the most striking of all the items on the page may be the one that Ware places on the porch of the building, at the very edge of its steps: “11,627 lost childhood memories.” Surely it is no accident that this page appears near the start of Building Stories’ “golden book” volume, an object whose gilt spine and cardboard cover summon up images of preadolescent reading, of those works that shape us in ways we can never fully recall.

With this sense of historical determinacy in the background, Building Stories turns from problems of the collective past to questions of personal memory. In one of the text’s most virtuosic sequences, Ware presents a cross-section of the ostensibly titular building, overlaying it with a catalogue of events and experiences that took place therein over the past century, along with the objects that filled it up: “296 birthday parties,” “68,418 orgasms,” “61 broken dinner plates,” and so on. This record of prior feelings, frustrations, and occasional pleasures, is notable first for the way that it detaches them from particular bodies. While Ware positions the accumulated orgasms, for example, over the female narrator, she sits placidly upright in bed, reading by herself. In their enormous numerical excess, these items outstrip the scope of any one individual form, indeed of any one life. While Ware letters this sequence with the same delicate cursive script he used when investigating Jimmy’s paternal past in his earlier novel, he pointedly detaches these terms from any single historical trajectory. What we find here, then, is something like a sedimented record of all those everyday banalities that must go forgotten if we are to continue going about our lives. Like the apartment building itself, which disappears into the weave of the text as a whole, these are the things we leave behind as we mature. Indeed, the most striking of all the items on the page may be the one that Ware places on the porch of the building, at the very edge of its steps: “11,627 lost childhood memories.” Surely it is no accident that this page appears near the start of Building Stories’ “golden book” volume, an object whose gilt spine and cardboard cover summon up images of preadolescent reading, of those works that shape us in ways we can never fully recall.

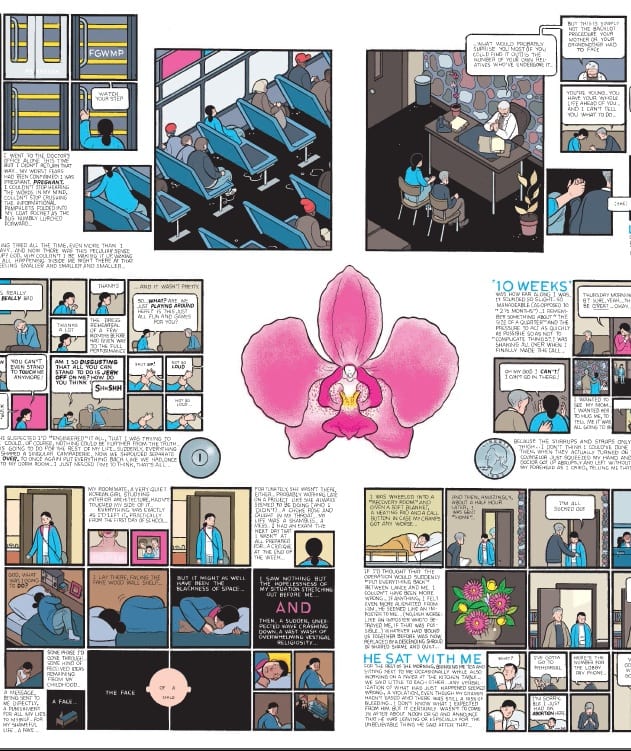

But if Building Stories calls paradoxical attention to necessary acts of amnesia, it also celebrates the awkward art of remembering, reveling in the way fragments of recollection constantly shape and reshape us. Ware organizes many of the book’s most formally compelling spreads around particular images, images that his individual panels circle like spokes on a wheel. These organizing emblems seem to be nothing so much as occasions for memory, sites around which otherwise distinct reflections cohere. Ordinarily, one strives to connect the diverse panels that make up a comics page by working through their temporal relationships to one another. By contrast, Building Stories often forces us to instead consider the thematic relations between the various sequences that make up each of these spreads, as well as their mutual bond to the central image that holds them together. Instead of making historicity visible as comics typically do, these sequences model something more like the contingencies of mnemenic reflection, wherein a particular experience or idea will summon up unbidden a host of others that came before. Much has already been made of the difficulties of reading the fourteen different objects that make up Building Stories. Absent some definite guide to their sequence, one confronts events with little certainty as to order or organization. But it bears noting that the stories within each volume often appear out of sequence as well. Accordingly, we are constantly led backwards and forwards in time, forced to make associations and connections as we go. The narrative past, present, and future come unglued from one another, reminding us that reading itself may also be an issue of memory, of what we recall and when we recall it.

Ware’s perplexing gamesmanship also extends to the ways that he has his characters tell their stories. In a number of episodes, the female narrator will describe some prior set of experiences from the vantage of retrospection even as the text’s visuals show her living through them. This disjunction between word and text recalls nothing so much as “Thrilling Adventure Stories” / “I Guess,” one of Ware’s earliest notable works. In this text, a narrator describes his childhood relationships with a series of disappointing father figures, superimposing them over the adventures of a golden age style superhero in ways that appear to be only tangentially related to the prose narrative. In The Comics of Chris Ware, I held that this piece should be read as a lament about the state of comics, a medium all too often understood as if it were always about costumed crusaders, irrespective of its actual contents. For all the formal cleverness of the story, its style suggests that the burdens of comics history have blocked the medium’s development, rendering innovation and novelty inaccessible to a larger reading public. Building Stories deploys a similar technique to merely indicate the necessary interrelationship of past and present. Importantly, the former no longer seems to impede the latter: The resurgence of yesterday underwrites, rather than obstructs, new action and experience today. To the extent that Ware’s new novel dwells on questions of memory, it suggests that the passage of time might allow us ever new and different access to what came before.

Some of the pages that Ware organizes around a particular emblem offer images of flowers, flowers not unlike those the female narrator sells early in her career and from which her successful business grows later in life. Straddling the slit between pages, these images are inescapably erotic, especially in relation to more explicit images of genitalia that Ware presents elsewhere. Insofar as they become avatars of new possibilities found in the remnants of old ones, these images suggest a movement past the profound blockages of sexual self-certainty that I identified in Jimmy Corrigan. Where those psychic snarls derived most powerfully from the pressures of familial history, as well as the history of the comics medium itself, Building Stories offers a more hopeful orientation toward the future. It suggests that by learning to live with both the memories we choose and those that choose us we can at last embrace the sense of maturity the medium has putatively grappled with for so long. Building Stories serves as a potent reminder – or perhaps a mass of mementos – that comics have never needed to grow up. They need only grow into their own material memories.

Some of the pages that Ware organizes around a particular emblem offer images of flowers, flowers not unlike those the female narrator sells early in her career and from which her successful business grows later in life. Straddling the slit between pages, these images are inescapably erotic, especially in relation to more explicit images of genitalia that Ware presents elsewhere. Insofar as they become avatars of new possibilities found in the remnants of old ones, these images suggest a movement past the profound blockages of sexual self-certainty that I identified in Jimmy Corrigan. Where those psychic snarls derived most powerfully from the pressures of familial history, as well as the history of the comics medium itself, Building Stories offers a more hopeful orientation toward the future. It suggests that by learning to live with both the memories we choose and those that choose us we can at last embrace the sense of maturity the medium has putatively grappled with for so long. Building Stories serves as a potent reminder – or perhaps a mass of mementos – that comics have never needed to grow up. They need only grow into their own material memories.