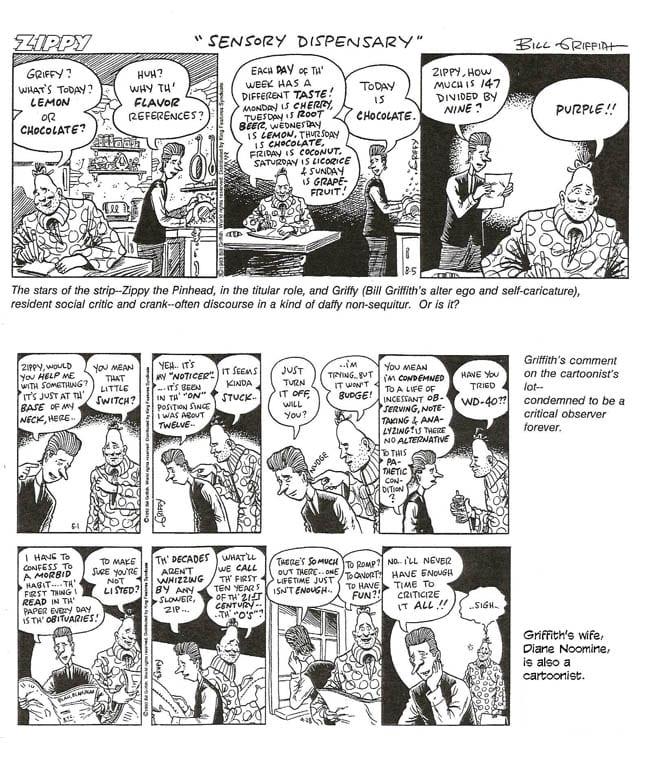

Zippy may be the title character, but he shares the strip with a cohort who is just as significant to the satire and commentary—Griffy. Griffy is Griffith, his alter ego. Griffy originated in another venue, however--a monthly feature called Griffith Observatory that Griffith produced for Rip Off's syndicate (c. 1977-1980). It combined, Griffith said, the social commentary aspects of two strips—Jimmy Hatlo's They'll Do It Everytime, and an obscure weekly strip by W. E. Hill that didn't always have a title but was called Among Us Mortals. (Griffith has collected a mound of Hill’s strip, and in November Fantagraphics will be publishing a collection soon after it brings out the next Griffith tome, Lost and Found 1969-1995, a 384-page collection of the cartoonist’s early work, most of it from his underground work in Tales of Toad, Young Lust, Arcade and many long out-of-print comics and magazines.)

Invoking both his name as commentator and the famed planetarium and telescopic observatory in Griffith Park in Los Angeles, Griffith used a drawing of the real Observatory as the strip's logo—but turned the telescope earthward. Griffy, the self-caricatured proprietor of the strip, functioned as a social critic—"a kind of cranky guy," Griffith said, "who is analyzing human foibles and criticizing them and tell people what they ought to do."

"So Griffy in that feature must've been functioning pretty much as he does now," I said. "There's a real tension between Zippy and Griffy. It's almost as if they have to be running in tandem like this in order to work."

"Actually, I think they are two parts of the same organism," Griffith said, "which happens very commonly with any team, from Abbot and Costello to Mutt and Jeff. You know the Mutt and Jeff syndrome in comics, where you have two fairly different characters who by themselves might be either boring or too much to handle. Until Griffy became a major character in the Zippy strip—which didn't happen until the early eighties and then didn't really blossom until 1985 with the daily strip—until then, I don't think I really had my approach down. I was waiting; I'd invented Zippy and I was kind of waiting for Griffy to join him for the whole thing to make sense."

Discussing the relationship between the two characters with Gary Groth in The Comics Journal (No. 157, March 1993), Griffith said: "Griffy tends to do his social rant, which in some cases Zippy just sits and listens to, just barely having a reaction. And in other cases, Zippy is integral to the way Griffy bounces off some particular topic because Zippy, in his unpredictability, can affect Griffy in different ways and also deflect some of that venom. All Zippy or all Griffy becomes too much—literally. It's like getting stuck on an elevator with a crank—or a pinhead. You'd go slowly nuts.

Discussing the relationship between the two characters with Gary Groth in The Comics Journal (No. 157, March 1993), Griffith said: "Griffy tends to do his social rant, which in some cases Zippy just sits and listens to, just barely having a reaction. And in other cases, Zippy is integral to the way Griffy bounces off some particular topic because Zippy, in his unpredictability, can affect Griffy in different ways and also deflect some of that venom. All Zippy or all Griffy becomes too much—literally. It's like getting stuck on an elevator with a crank—or a pinhead. You'd go slowly nuts.

"But there are two halves making a whole at work here," he went on. "Zippy and Griffy together almost make a third character. It's the manifestation of an interior dialogue. I think Zippy is part of me, but I'm not Zippy. Whereas I'm more Griffy than I am not Griffy. But it's undeniable that there's a large chunk of me that is Zippy. The Griffy impulse to analyze or criticize is always on the surface of my brain. So what Griffy and Zippy represent is the dialogue between those two parts of myself, the critic and the fool."

Character, Griffith told Groth, is central to the success of a comic strip. "That's the essential thing," he said, "—that makes any comics that I read compelling or not: whether they're alive or not. It's a real trap for a lot of cartoonists to get hold of an idea but not bother to breathe life into the character, and let less compelling reasons for doing comics take over. The starting point for any comic strip is the character, a real, living, breathing person with a history."

The expression "non-sequitur humor" has been used in describing Zippy, and I asked Griffith about it.

"It was first used by people writing about Zippy," he said. "And on the surface, I would agree. A lot of the dialogue appears to be non-sequitur; but once again, that's not how I write it. And if you were to eventually get on the wave length and enjoy what I'm doing, you would see that the random quality of those so-called non-sequiturs makes its own kind of sense. It's not really nonsensical.

"It's not surrealistic, either," he continued, "—another phrase that is used constantly to describe my strip. I understand the reason for using that term, but it's not a particularly accurate one. It's not surrealistic; it just doesn't take place in the ordinary comics universe. But it's not surrealistic. It makes sense; it just doesn't make sense in the same way.

"Sometimes I'll do a strip that's actually frighteningly traditional, even. There'll either be a very distinct and obvious structure with a punchline or I'll make a satirical point that absolutely anybody can get because it's about, say, Clinton or somebody. I don't consciously do one or the other, but I'm aware that I do a range from complete and utter insider strangeness all the way to almost Ernie Bushmiller kind of gags, where the punchline is right in your face."

I said: "I think of Zippy as an example of someone who is just completely absorbed by popular culture or television commercials, and who takes all of that as being the Real World."

"Ummm. Yeah, he takes that as his environment. The swirling information society to Zippy is as comfortable and as natural to him as someone taking a hike in the woods feels about the woods and the air and the wonderful nature sounds. Zippy is equally at home in a completely media-soaked information-overloaded environment, which is what we're all subjected to every day, and if we didn't tune out most of it, we'd go insane."

"Or we'd be like Zippy."

"Or you'd be like Zippy who gave in—long ago—and just happily embraced the whole thing, which gives me a great point of view from which to make fun of it all."

"Right," I said. "On the barest surface level, here's this character so taken, so submerged in this artificial environment—"

"Right."

"—that you have to think twice about how much of it you're buying yourself."

"Exactly," Griffith said. "Exactly. And also there's the quality of Zippy being somewhat of an innocent, a slightly Chaplinesque figure, not a child but having some qualities of a child in the sense that he will take things at face value at first, but Zippy takes so many things at face value so quickly that it's not really child-like at all. He will take things at face value and thereby turn them inside out, but see them from a different point of view the way a kid will be brutally frank without really intending to be."

"There's a kind of poignance, it seems to me," I added, "—there's this impenetrable placidity about him. You think, Oh, there can't be anything wrong with his life at all. And yet, there's a little element of insecurity there: he's always asking, Are we having fun yet?"

"Oh, I'm glad you saw that," Griffith said. "A lot of people think Are we having fun yet? means, just, Where's the next party? But it's more of an existential question. It almost begs the questions, What is fun? Why do we have to have it? Where is it? What is it? Another phrase that is used by writers and critics about Zippy is "existential humor." That probably relates a little more to Griffy than Zippy, but it's existential in the sense that it is a sort of questioning kind of humor about everything that happens; it doesn't accept the world so much as hold it up for examination."

In his interview with Groth, Griffith discussed the role of the satirist: "I gave a talk once, and afterwards, someone asked a very pointed, interesting question—Do you basically think people are good or evil? I said, I guess I think people are essentially good enough to make fun of. What that means to me is that I feel an affection of sorts for the target of my satire or anger. I value, in a way, the thing I hate. I need it. All satirists, in my experience—satirists that I like—have that quality. They're metaphorical bomb-throwers, but they wouldn't ever pick up a real bomb and throw it. That would destroy the thing that they want to make fun of. They want to change it, they want to criticize it, they want to point out that the emperor has no clothes, but they want the emperor to still parade around. If you don't identify with your target a little bit, at least see its humanity, the rage loses its humanity."

Griffith sends in his batches—six dailies and a Sunday—every Thursday. He works six days a week; never on Sunday. "If I'm going to be doing some work besides the daily strip," he said, "I always do the daily strip first in the morning because that usually is what has to be the most spontaneous, and my mind has to be at its peak, and as with most people, I'm pretty good after breakfast and my morning walk—my little bit of exercise—I do my writing best in those two-three hours after I get back from the walk." He arises about nine o'clock every day and goes for a 45-minute walk after breakfast.

"Usually on the walk, I'll have two or three ideas, and by the time I come back, at least one of them will seem reasonable. And I do what everybody else does: I keep a notebook, and I constantly jot down codewords for ideas, some of which I understand when I read them later—some of which I don't. And I take a lot of notes on conversations—a lot of verbatim conversations, I find myself writing down. And then using them or not using them. Just a habit. Eavesdropping. A lot of eavesdropping."

"I do a minimum of one complete strip a day. On at least one day a week—two or three if I'm being good—I'll do two strips a day so that I'll build up that little bit of cushion so I can take some time off."

Describing his drawing style as a "combination of Will Elder and Reginald Marsh," Griffith says his pencils are "medium loose—more [complete] than loose but not tight. I don't have to have it really tight before I ink."

"So you're actually drawing when you're inking rather than tracing a pencil drawing," I said.

Doing a daily strip suits him perfectly, Griffith told Groth: "The daily strip, aside from being somehow appropriate to Zippy's soundbite mind, is also appropriate to my wide ranging desire to understand everything I see and to summarize it or praise it or point out something about it. To me, it's just this wonderful opportunity. It's almost like writing in my diary. I can't think of any other comics medium where that works quite as well as the daily strip where you can just turn on the tap and keep it going."

My favorite story about Zippy is rooted in January 2002, when Zippy disappeared, briefly, from the pages of the San Francisco Chronicle at the first of the year. In the consolidation maneuver with the San Francisco Examiner, the Chronicle inherited all the other’s syndicated content, and, seeking to reduce the combined roster of comics so all would fit into the paper’s customary comics alcove, the paper conducted a readership poll by which it determined that seven strips were low enough on the popularity scale to risk dropping: Spider-Man, Curtis, Family Circus, Marmaduke, Piranha Club, Sylvia, and Zippy.

Zippy was first published in the mainstream by the Examiner in 1985, and Griffith was understandably miffed that this sentimental home suddenly shut him out. He promptly mustered Zippy’s fans by e-mail. Telling them that newspaper editors are “very responsive to reader reaction,” he urged them to protest. “You can bring Zippy back,” he said.

Only about 4 percent of the Chronicle’s readers participated in the poll, Griffith observed later. And because the older readers of newspapers are more likely to respond to surveys, the poll clearly overlooked Zippy’s fans, who tend to be younger and hip. They are the sort who can understand Zippy’s conviction that the America portrayed in advertising is not an artificial construct but actual reality, a conviction that opens the door to a host of nearly philosophical murmurings by Zippy and his cranky cynical cohort, Griffy, about the nature of life itself. For Zippy, life is a happy picnic of glazed donuts, Ding Dongs, and taco sauce at a vintage bowling alley in Hollywood. For Griffy, life is a struggle to discover meaning. Zippy’s only concession to Griffy’s perplexity is his perpetual query, “Are we having fun yet?”

Zippy’s fans mustered outside the Chronicle building on January 17 to protest Zippy’s demise two weeks earlier. Several were dressed in Zippy’s clown costume. Others handed out free Ding Dongs and taco sauce. The plan was to pelt the building with glazed donuts until management conceded defeat and restored Zippy to the funnies page.

But the Chronicle frustrated the plan: deputy managing editor for arts and features, Michael Parrish, appeared at the front door and announced that Zippy would be reinstated. Zippy’s supporters cheered and lofted donuts into the air. They had won. Then they fell silent. What would they do now? They had rallied. To what purpose now? Then one man, who clearly understood Zippy better than the rest, started a chant: “Cancel Zippy! Cancel Zippy!” And the crowd joined in.