Stuart Immonen has been making comics for more than three decades and in that time he’s become not just one of the great superhero artists, not just one of the great science fiction comics artists, but one of the great comics artists of his generation. He’s been one of the major Superman artists of the post-Crisis era, which includes a long run as an artist and a writer on the monthly books and drawing and coloring Superman: Secret Identity, he’s one of the major Spider-Man artists of the 21st Century (both Ultimate and Amazing Spider-Man). He drew major crossovers for both DC (Final Night) and Marvel (Fear Itself) and runs on titles including Legion of Super-Heroes, Captain America, All-New X-Men, and New Avengers. Immonen wrote and penciled comics like Inferno and Superman: End of the Century. He’s drawn books for Humanoids and Revolutionary Comics, and was one of the co-founders of Gorilla Comics. Along with Warren Ellis, he made Nextwave: Agents of H.A.T.E. and is co-creator with Mark Millar of the bestselling series Empress.

Stuart Immonen has been making comics for more than three decades and in that time he’s become not just one of the great superhero artists, not just one of the great science fiction comics artists, but one of the great comics artists of his generation. He’s been one of the major Superman artists of the post-Crisis era, which includes a long run as an artist and a writer on the monthly books and drawing and coloring Superman: Secret Identity, he’s one of the major Spider-Man artists of the 21st Century (both Ultimate and Amazing Spider-Man). He drew major crossovers for both DC (Final Night) and Marvel (Fear Itself) and runs on titles including Legion of Super-Heroes, Captain America, All-New X-Men, and New Avengers. Immonen wrote and penciled comics like Inferno and Superman: End of the Century. He’s drawn books for Humanoids and Revolutionary Comics, and was one of the co-founders of Gorilla Comics. Along with Warren Ellis, he made Nextwave: Agents of H.A.T.E. and is co-creator with Mark Millar of the bestselling series Empress.

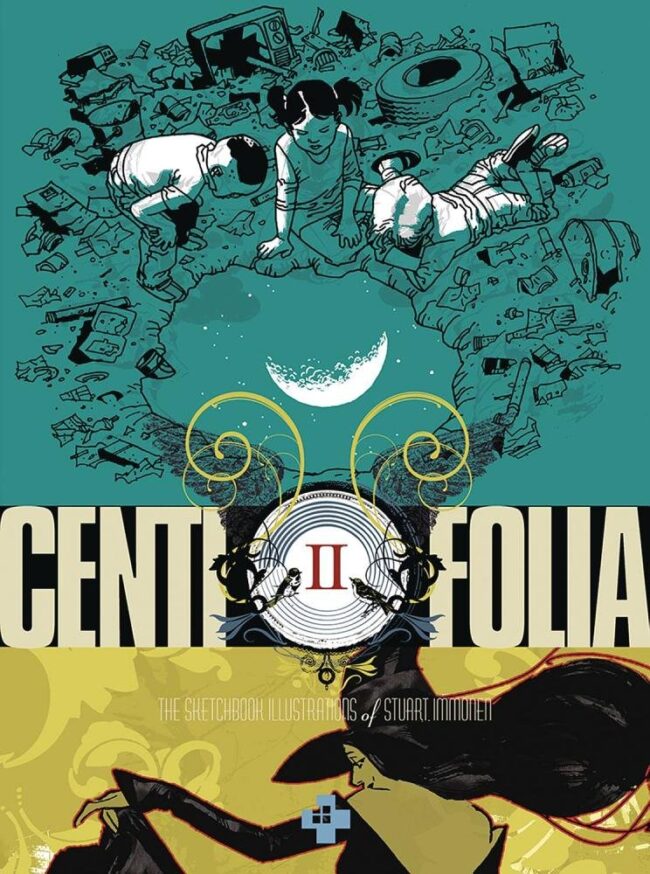

Immonen has long been both a fan favorite and an artist’s artist. So many creators have long talked about Immonen’s work in respectful if not awed tones. The way he adjusts his style for each project, his masterful skill of depicting character through body language and expressions, his eye for composition and design. In his two published sketchbooks, Centifolia I and Centifolia II, Immonen might disappoint those fans looking for pinups of famous characters, but he shows off how he draws and how he thinks.

Throughout his career he’s been making more personal work like Never As Bad As You Think, Moving Pictures,Russian Olive to Red King, and Grass of Parnassus, all of which are collaborations with his wife Kathryn, and show off an incredibly experimental side as each project experiments not just with design and style, but with how they work and how the work is presented. I’m honestly at a loss for the sheer virtuosity. How many comics artists could draw superheroes as well as anyone ever has, and then turn around and make something like Moving Pictures? It would be like James Cameron making Ingmar Bergman dramas in between action thrillers. Needless to say, a lot of people seem not to know of everything he’s done, and fewer know what to make of it.

After a run on Amazing Spider-Man that concluded with issue #800, the Immonens launched Grass of Parnassus on Instagram. Currently he’s penciling and inking Plunge from DC, a miniseries written by Joe Hill. We spoke recently over e-mail about his life and career, the way he prefers to work, and debunking the rumor that he retired.

When you were young, what were the comics you read? What was the work that made you think, this is what I want to do?

I'm old enough to have grown up pre-comic specialty shops, so I read whatever was at hand. I didn't have money of my own, really, so my earliest comic experiences were dependent on the generosity of my mother, probably to keep me quiet on long road trips or at the supermarket checkout. My maternal grandmother also always seemed to have a few issues in a drawer whenever we visited; three-packs of completely random things – a Kirby Captain America, a Gold Key issue of the Harlem Globetrotters, Richie Rich, Turok Son of Stone. At one point our library had some Tintin albums and Crockett Johnson's Barnaby, which I obviously recognized as being comics, but very different from the pamphlet material. I read Peanuts religiously.

When I eventually had a modest allowance, I spent it on comics. Again, I was at the mercy of the terrible newsstand distribution of the time; on Saturday mornings I bicycled a circuit of the three convenience stores in the neighborhood which had comics and came away with whatever; I liked Spider-Man and the X-Men, but would also buy a Harvey comic or Archie. But it was never a lot – I just didn't have the money for it. I kept buying into my teens, but my "collection" was never more than a small box of read-to-shreds issues stored on the floor of my bedroom closet.

From an early age I would copy drawings from comics; somewhere there probably still exists a sketchbook of my versions of Samm Schwartz’s Jughead and Sal Buscema's Hulk, which are maybe odd primary source choices but thinking about it now, I have come back to that kind of angularity in my own drawing many times since. I drew all the time but I wasn't interested in telling stories with pictures... or maybe didn't understand how. Apart from an attempt to pitch a newspaper strip to our local when I was nine or ten – I did fifty strips and received a polite but firm rejection – I didn't really make comics at all until Kathryn and I did Playground the year I turned twenty. I was sort of pulled around by different kinds of art making, and found myself frustrated in university because the institutional goal was to focus students on a single discipline, and I wanted to do all sorts of things. Or perhaps, at eighteen, I hadn't found the thing I wanted to commit to, so I left after one year. This coincided with disposable income for the first time in my life, and access to several comic shops.

So, what comic made me think I could work in the business myself? Okay, I do actually have an answer. In amateur ornithology, there's what is commonly referred to as a "spark" bird – the sighting that turns you into a keen naturalist. After over a decade of reading comics, the work that finally registered in that way was Ted McKeever's Transit. That being said, the motivation wasn't so much a desire to want to make comics as it was a realization that was possible to make comics. For someone with an aptitude for drawing but no training and just basic education, it's possible it seemed like there weren't many other options.

You started your career making and self-publishing work back in the 1980s in Toronto. What was the comics and just the art scene in Toronto like back then? Who was around, what was inspiring you, what were you doing?

People remember the black and white boom now mostly in terms of the negative economic impact – flooding the market with unsellable material and rampant speculation – but for me, it was a creative highwater mark, with shops carrying small and medium press books that otherwise would not have been made so widely available. In addition, comics were being made and published by Canadians – some in Toronto, some elsewhere – which drove home for me that working in the industry was available not just to those in proximity to a couple of large companies in the US, but to anyone, at any scale. So, there was Cerebus of course – Dave Sim was actually the first person to pay me professionally, for a single page strip in the back of a Cerebus reprint comic – and Hancock and Cherkas' Silent Invasion, David Boswell's Reid Fleming, and Toronto publisher Vortex's line; Yummy Fur, Mister X, Ty Templeton's Stig's Inferno, the Vortex anthology and so on. There was a healthy and visible zine culture at the time, too. Crad Kilodney was a well-known fixture on the streets of Toronto, hand-selling his pamphlet fiction on the sidewalk. Nerve magazine was a two-color monthly music tabloid which published the work of friends I knew from working in a record store. I had a handful of pretentious boho strips published in Eat Me, Literally. Stores like PAGES and City Lights carried all kinds of one-off and obscure stuff.

Vortex’s Bill Marks in fact, specifically led us to self-publish. In early 1988, he (generously, thinking back on it) agreed to meet with Kathryn and I in his office above the Silver Snail comic shop to look at Playground, which we (presumptuously) hoped he would publish. My recollection is that he looked at the pages an agonizingly long time before suggesting we might consider making a mini-comic for a while and then get back to him. It was a reasonable comment, given our total lack of experience, but at nineteen years old, my internal monologue ran, "OK, I WILL."

But if there was a community – like an Algonquin Round Table of cartoonists – we were unaware of it. The contributors to Headcheese were mostly film students, friends of friends from school. Only a couple of us did more comics afterward; Kathryn and I of course; Sheldon Inkol and I did a couple of issues of Nut Runners for Rip Off Press, and Ron Boyd worked for many years for Marvel and DC. As I suggested earlier, I'm not sure what motivated any of us to make comics specifically; it just seemed like a fun, creative endeavor which was not beyond our means financially. We all had other jobs. I'm quite sure we didn't think at the time that it would be a career – or even a money-maker.

Was Playground the first comic you made? Or was it the anthology Headcheese?

Yes, Playground was our first effort, though we published Headcheese concurrently, three issues of each. Caliber Press published an additional issue of Playground about a year later. As to what it was, well, what we told people was that it was a “punk rock murder mystery," except the murder was accidental and there was no mystery about it, as it happens in panel in the first issue. Thinking about it now, it was an exploration of mortality and coming to terms with profound loss, which is the subject we keep coming back to thirty years on. Certainly in Russian Olive To Red King, but also in Moving Pictures, and even Never As Bad As You Think and other small projects. Mostly, it's about the people who have to deal with the mess left after the dust settles. Oh, and talking animals. That's kind of weird for two kids who were barely twenty.

You worked for the famous – or infamous? – Revolutionary Comics for a while and worked on Rock n Roll Comics. What comics did you draw for them?

As a publisher, Revolutionary definitely made a name for itself on the back of being "unauthorized and proud" or words to that effect, but dealing with Todd Loren was a dream especially compared to other unsavory types I've had the misfortune of conducting business with. Todd paid very little, but always promptly, and was supportive of the work (he let me paint covers sight unseen, something never to recur in my career), and never asked for extensive corrections. This was an incredibly positive experience for me, while I was in every sense learning on the job.

The first book I did was a revamp of their initial release, a Guns 'N' Roses biography with new material. I did quite a few stories; Motörhead, Anthrax, 2 Live Crew, Prince, The Beatles, ZZ Top, and some smaller jobs.

At this time, what were you reading, and did you have this goal in mind of working for Marvel/DC? Or what did you want at this point?

I was probably reading Neat Stuff and Eightball and Love & Rockets, but by the time I was working for Revolutionary and Innovation and Rip Off, I had left my day job managing a comic shop in Toronto and had pretty much committed to the idea of being part of the traditional corporate structure of assembly line comics. Kathryn was concentrating on school and I didn't feel confident that I could lucratively pursue life as an auteur cartoonist alone, especially after mailing portfolio work to Fantagraphics, Drawn and Quarterly, Kitchen Sink, et cetera and – apart from Denis Kitchen who was encouraging – not getting any response at all. I concentrated on pencilling, and was submitting to every company and editor I could think of, until I finally got a face to face meeting with Neal Pozner at DC, who offered me a ten page sample story written by Len Wein. It was all pretty swift; From Playground to regular DC work was only about five years. I wanted to draw, and I needed to earn money to keep doing it; I had no issues with owning the material or with collaborating with others – it was all comics to me, but pursuing the mainstream was definitely a practical decision.

The black and white indie movement was fading by this point – even Ted McKeever was making color comics for Marvel's Epic line. I was reading that, and Akira and Hellboy and Why I Hate Saturn, so, all over the map as usual, but I was seriously modeling my own art on the clean-line work of Adam Hughes, Alan Davis and Kevin Maguire among others. Not only was it salable, but it seemed much easier to reverse-engineer than what was happening at the same time at Image. Not that I actually figured it out – I'm still trying – but it was a place to start that made sense to my eye.

The Len Wein story you drew, was that the Martian Manhunter story you did for Showcase ’93?

That's right. Showcase had, as I understand it, a dual purpose; to couple established talent with newcomers so that there was at least some sales hook for readers, and also to use in-house for editors to gauge how well less experienced creators would work in a collaborative environment and with characters the editors knew and understood.

How soon after pencilling that did you end up pencilling Legion?

Pretty much right away. Michael Eury saw the Showcase piece and needed an inventory story done for Legion. Then, when he transitioned off the title and KC Carlson came in as editor, Jason Pearson was also leaving as penciller and KC asked me to start based on the one-issue fill-in. In the middle of the personnel shift, the inventory piece ended up being needed right away – I guess it was possible that it was commissioned for this very reason. It was published as my second issue as regular penciller. As has happened many times since, I was very lucky to be in the right place at the right time, but it was also a case of building on a series of successes.

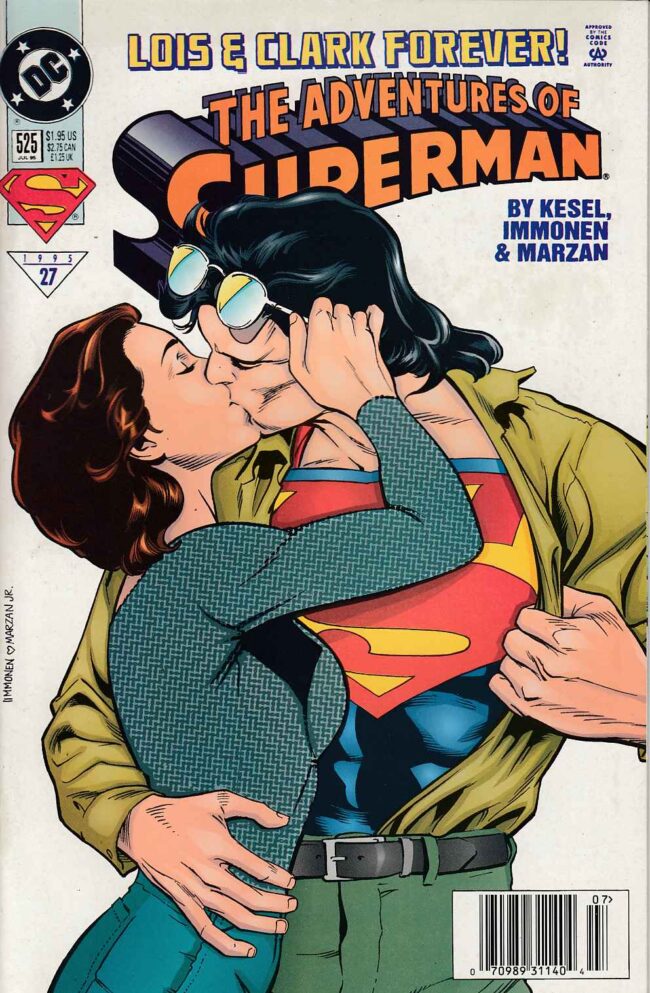

You drew Legion for over a year and then moved onto Adventures of Superman, do I have that right?

I believe I did twenty-four issues of Legion, so two full years, and pencilled two fill-in issues of Superman for Mike Carlin around the end of that run. Then, yes, I moved over to Adventures for a while and stayed on that and Action for another four years I think.

This isn’t too long after the Death and Resurrection of Superman saga. Was it a big deal to be penciling, and then writing a Superman title? Especially not long after you started working at DC, relatively speaking.

Every job I take, even now, comes with butterflies. I recognized from my own experience as a reader that comics are a discretionary hobby and I respect that people are spending their entertainment dollars on my work when that money could easily go somewhere else. More than that, no matter what project you're on, someone's always going to be a bigger fan than you; you owe it to the reader who's been with the book for years to do your best work, so yeah, a big deal in that way, but as I say, every job is like that.

As to whether or not I felt up to the task, I'll tell you that have a complicated relationship with my own work and am often frustrated, which may go some distance in explaining why I've shifted gears so often. Early on, I felt like I was learning and improving at an explosive rate, and probably felt like the improvements in my career outlook were keeping pace with that development; working for smaller publishers turned into working for Marvel and DC; a sample story turned into a fill-in, which turned into a series offer, which turned into a better series offer. I had good relationships with my editors; KC Carlson (who joined the Superman office not long after I did) and Joey Cavalieri in particular were very encouraging and supportive, and the general atmosphere in the Superman group was very inclusive, with regular summit meetings for all involved, not just the writers. It's a totally different environment now, across the industry.

As far as writing, was that something you wanted to do and you were pushing for?

I don't recall exactly, but the opportunities arose in the same way as with drawing; a ten-pager in Showcase led to the Inferno miniseries which led to Action and the Superman: End of the Century OGN. It must have seemed foolish to not seize them. But ultimately, it was more work than I felt able to handle well, and I honestly think I was not the best fit for Superman. My stories invariably tended to be experiments which interested me; a re-telling of Chaucer's Chanticleer from the point of view of Lex Luthor; the history of Superman's villains in the visual style of McCay’s Little Nemo; there was a story in which the panel count on successive pages increased exponentially. I think I squeezed 256 panels into the last page, and End of the Century, which had watercolor paintings and puzzle elements similar to the armchair treasure hunt books of the late seventies.

Anyway, once I stared having to give up drawing some issues in order to complete writing assignments, I was pretty sure I was not on the right path anymore.

Was Adventures of Superman when you started working with Jose Marzan, Jr.? You’d worked with a few inkers before this point, but you two seemed to have clicked and went on to work together for a while. What was it about your collaboration that you think worked?

Jose was a conscientious and consistent art partner who lent a maturity to my drawing which hadn't been there before. He'd been trained in this classical way by Klaus Janson and made the linework look more confident than it probably was. I also realized at this time that it was easier to modify your own work to better suit a collaboration than it is to get someone else to change. There was quite a lot of pinup and cover work to be had in the 90s, so I got to work with a range of inkers; Klaus, Kevin Nowlan, Dan Panosian, Tommy Lee Edwards, John Dell, Karl Story, and on some longer projects with Terry Austin, Joe Rubenstein, Dick Giordano and Wade Von Grawbadger.

Coming up from indie comics where you had inked yourself, where you could ink, what was it like trying to find collaborators you could really gel with? Especially considering working on a monthly book and the constant deadlines

Yeah, you're always behind the curve, and for me it takes quite a while – several issues usually – to really get comfortable with all the elements in play and to figure out what works well and what doesn't. I've always hated my own inks, and knew I couldn't make improvements in that department while drawing a monthly, but when I started working with Wade, I knew I had found someone who was very sympathetic to my own ambitions and similarly willing to move the goalposts if the situation merited it.

During your years working on Superman, you drew Final Night. Which was a different kind of crossover event. It feels almost quaint after decades of nonstop events. You and Karl Kesel and Jose had been working together before. How did you end up killing Hal Jordan?

No disrespect to Karl, but to be honest, I don't remember much about this series. I think I had thrown out an idea at one of the Superman summits about what effects the sun going dark might have on Superman's powers. Karl worked it up as an annual, I believe, and editorial decided it was a bigger idea than would fit in a regular issue. I tried something different with my drawing for it and I don't think it really worked at all, unfortunately.

You mentioned working with Wade von Grawbadger before Inferno on some covers or pinups. When did you first meet and how did you two end up working together on the miniseries?

Yeah, we'd done a Supergirl story for Showcase '96, I think. And I had drawn a page in a "jam" issue of Starman, which Wade made look nicer than it really was. We met at Dragon*Con in 1993, and got along right away. After the convention, we stayed in touch. Whenever a short side project came along, we asked to work together. I'm not sure if Wade was done on Starman by the time Inferno ramped up. He may have been doing other things at the same time. I guess this was before I was writing and drawing Action, but maybe while I was drawing Adventures? Seems incredible now, if that was the case.

I’m not a Legion fan, but I remember Inferno – and it stood out at the time – for the covers. And I’m just curious about what you wanted to do there and what the response was at the time?

I guess I floated the idea of having the series covers resemble magazine covers; SPIN, Seventeen, that kind of thing, to line up with the John Hughesian cast of teen girls. I’m not sure how successful it was. It certainly had no impact on sales, and I think there was a lot of grumbling in DC's production department concerning all the extra design and font work.

I have not been able to track down a copy, but you pencilled the Spider-Man/Gen13 crossover in 1996? How did you end up drawing a Marvel/Image crossover?

That's a good question! I'd worked for Marvel here and there before that, but I think this was the first job I may have done for Tom Brevoort, who fed me lots of side gigs in the late 90s and early 2000s, which grew into more regular work later. But I don't think we had any kind of track record before this, so it seems like an anomaly in terms of when it was published and who was involved. I guess they just needed a warm body.

You mentioned Superman: End of the Century before and I like the book, but I think that book and some of your other writing has more in common with the work you’ve done with Kathryn than say the average superhero book. Is that fair?

I think so. Again, it was a Superman story that didn't have Superman as the focus, and that's entirely my failing. I think I was probably more interested in the technical aspects, doing some painting and integrating the puzzles. This probably convinced me that I was not cut out for writing, at least not corporate comics. At this time, I was also illustrating kid’s puzzles for Robert Leighton’s Puzzability company, and doing some gag strips for Chris Duffy at Nickelodeon magazine, but there was a lot of competition for few spots and the rejection rate was quite high. I liked the limited scope of crafting a couple of panels with a punchline, though.

I guess it feels like in some ways you would be a bad fit to write a monthly superhero book because you like to experiment and find new approaches – and then do the same artistically. It feels like it would be very easy to butt heads with the company or burnout. Though it sounds like you had a really supportive team and environment then.

If there was opposition from higher up at DC, I never knew about it, but maybe it just stopped at the editor. I think there was a fair amount of latitude as long as sales didn't nose dive, and being a cartoonist himself, Joey Cavalieri in particular had an appetite for a broad range of comic-making approaches. When Eddie Berganza succeeded him, and brought in Joe Kelly and Jeph Loeb and so on, I felt like my time on the Superman titles was drawing to a close.

Was there anything in particular that made you feel like your time on Superman was drawing to a close?

As I say, there was a change in editorial, and many of the creators with whom I'd developed relationships had also already left for various reasons. At my last creative summit, with all new faces at the table, I felt like things would move forward better without me as a vestige from the previous regime.

I keep thinking that after Crisis, there was a run of writer-pencillers on the Superman books like John Byrne and Dan Jurgens and Jerry Ordway, George Perez was doing that on Wonder Woman for a while. There haven’t been too many writer-pencillers on the monthly books since then.

Perhaps that's true on the Superman titles – I haven't kept up, to be honest – and having that track record surely paved the way for me to adopt that role, but after I left there continued to be and still are writer-artists at DC. Ultimately, it's a role that never felt comfortable to me, but given the current imbalance of authorship credit across the industry, it's something I would recommend for anyone trying to break in if for no other reason than to be able to exert more control over one's career trajectory.

After Superman, how did you end up being a part of Gorilla Comics?

Kurt [Busiek] phoned me up and asked me. I don't think I was his first choice as collaborator, since the rest of the group and the business plan were both already firmly established, but Kurt made it clear that it was a clean slate as far as creative collaboration was concerned, and we found common ground in working up Shockrockets together quite quickly.

What was the appeal of joining Gorilla? Was it working with Kurt? Doing something creator owned? Something not superhero?

Well, all of the above, really, though I didn't put all my eggs in one basket. Through the late 90s and early 2000s, I cast a fairly wide net, working for Top Cow, CrossGen, Marvel, plus non-comic illustration work for some magazines, tabletop gaming and stock media providers. Still, Gorilla appeared to be well-organized with some heavy hitter talent behind it, and it still seemed like a flush time for comics with potential for growth. The project went kind of sideways in the end, but I was grateful to be working with Kurt, who really wanted the books to succeed and stuck his own neck out to make it happen.

We all believed that there was room in the marketplace for successful non-superhero fare, and we were right – it just happened much later when The Walking Dead and Saga caught fire. Now I suspect there's too much of it, selling in unsustainable numbers. When shops open up again, we may be looking at much leaner times.

You worked on two projects with Busiek at Gorilla, Shockrockets and Superstar. Both of which I liked, but Shockrockets was this acchance for you to create a world from scratch?

I'd counter with the suggestion that every comic – even single issues – involve quite a lot of world-building, but I take your point. Even though I was presented with the opportunity to develop the visuals for a society and technology that had no precedent, I actually think this is not Shockrockets' strongest aspect. I think the look was serviceable but generic sci-fi, which speaks to a lack of imagination on my part. But then I haven't looked at it in a long time, so maybe it's better than I remember. I think the character work was solid – this is certainly a strength of Kurt's as well as mine – but I feel like I could have done so much more with the production design. Superstar was an idea that Kurt had thought of many years earlier, and had actually worked on with other artists including Alan Davis before I had a go at it. I'm not entirely sure why it was added to Gorilla's output except maybe as proof of concept.

It was around this time that you drew Sebastian X. How did you end up working for Humanoids?

The Gorilla titles were licensed for the French market by a publisher called Semic. I was approached by a rep from Humanoïdes at a store signing or festival – I don't recall which – while promoting Shockrockets in France, and Sebastian X was proposed to me. I accepted and honored the contract and finished the job, but otherwise have nothing whatsoever to say about it. At this point, I have no connection to the project, legally or otherwise.

After the end of Gorilla Comics, how did you and Kurt come to work on Superman: Secret Identity?

Gorilla was financed out-of-pocket, so we were both looking for paying work. Kurt as usual did the heavy lifting as far as the formalities and logistics of pitching the idea, which again was one he'd had for a long time, but it definitely helped that Joey [Cavalieri] and I had a strong established relationship. We had oars in a few different waters at this time – we were also in extended talks with Tom Brevoort over an idea set in 1950s Marvel but for whatever reason, things fell into place at DC first, or better.

You drew and colored the book and I wonder if you could talk a little about your thinking about how you wanted the book to look and feel.

I recall having a conversation with Alex Ross in which he reacted with strong disbelief to my assertion that I used photographic reference in my work. This sat with me for a long time and eventually I took it to mean that I wasn't working hard enough somehow. Achieving a naturalistic look is – for me – not easy, but given enough time, I thought it was possible. I spent all of high school drawing realistic pictures of David Bowie and Duran Duran and so on from photographs, but had largely abandoned that approach in my working life, apart from the painted pages in End Of The Century. I had also been messing around with Photoshop since version 3.0 when it came on a couple of floppy disks, so there was I guess some kind of confluence of back-burner itches I wanted to scratch – the artist's equivalent to the pitch a writer sits on for years, maybe.

Kurt's idea of a Superman story set in the real world – a world without superheroes except in fiction – in which it made visual sense to draw naturalistically and without exaggeration, coupled with a long deadline and a finite page count, seemed like an ideal place to experiment. There was the smallest amount of resistance and doubt from some level of editorial, even after I'd submitted some samples of how I wanted it to look, and the standard production specs did not apply, so I ended up doing some covers using the technique – for Just Imagine Stan Lee Creating the DC Universe – and – maybe more inexplicably – a Captain America story for Marvel which Kathryn scripted.

Once I got into actually drawing Secret Identity, I struggled with feelings of being overwhelmed by the scope of the project and perhaps having bitten off more than I could chew – normal modus operandi – but having a long lead time allowed me to work through the problems and develop a methodology and visual vernacular I could reliably repeat. In fact, the coloring workflow I developed for myself then, which is laborious both from a human and computing-power standpoint with sometimes scores of semi-transparent layers, is basically how I still work, the digital equivalent of dry-on-dry watercolor. Even something deceptively simple like Grass Of Parnassus has a ridiculous number of steps.

What surprises me most is when people tell me that Secret Identity looks "painted" when it seems very obviously "computer-y" to me. I guess the combination of the soft pencil line and the limited palette are what people see, and not so much the blockiness of the color. My own experience of mostly seeing the pages on screen as opposed to paper probably has a bias as well.

We were talking before about Superman: End of the Century and how it wasn’t exactly what people expected of a Superman book, Secret Identity wasn’t what people expected a Superman book – and one drawn by you – to look like. Which I feel like is what you want – though it’s not necessarily what companies want.

Well, DC was behind Secret Identity right up to the end. When it came to collecting it into one volume, I felt like there were some stumbles – a softcover with thinner paper stock than the original prestige-format issues – but these are budget and marketing matters over which I have no control. As a creator, I want to see the work be presented in the best possible light, but there are always going to be other practical concerns. However, I was miffed enough to withdraw from pursuing more work at DC and I was fortunate enough to continue to be able to pick up jobs elsewhere.

As far as Superman: Secret Identity, I do love the naturalistic approach you used for the book and I would love to see you do more of that.

Thank you. I hear that a lot, actually, but I'm not sure I would return to it on another project. I think it's very seductive – it's pretty to look at – but creatively doesn't provide many options for exploration. Scott McCloud talks about this in Understanding Comics – there's so much more you can do with a cartooned representation as opposed to something realistic and I think there's also something to be said for creating some friction between the writing and art, as in when they're sympathetic, but don't press all the same buttons. Generally. This is not a universally held view – some people prefer the work of a single auteur to collaborations – but I think this slight disparity of approach is why Kurt and I worked well together.

As far as drawing and coloring a book and all that involved, is the workflow just too time-consuming to do that on most projects? Would you like to do more?

Yeah, the workload was massive. Part of that was my inexperience in coloring, but I was also purposefully leaving quite a bit of the “drawing” for the color stage, so I was probably spending as much time on that task as on the line art, a day or two each. From pitch to store shelves, Secret Identity was more than two years in the making, so 600-plus days for a 200 page book. As I said, I took on occasional finite jobs at the same time, partly to recharge and partly to maintain a presence in the marketplace, but on the whole, I was concentrating on one gig for quite a while.

Obviously, I drew Russian Olive to Red King and Moving Pictures over comparable spans, and Grass of Parnassus for a year, so when you ask if I'd like to do more, I feel like I haven't stopped, though the "day jobs" have obviously been other things.

You mentioned how you and Kurt were talking with Tom Brevoort about doing something at Marvel. Around that time you drew six issues of Incredible Hulk, working with Bruce Jones.

The Hulk run came after Secret Identity was wrapped up. Tom fed me jobs as often as I thought I could handle them since that Spider-Man/Gen-13 one-shot. There were issues of Avengers written by Kurt, and a couple of issues of Fantastic Four written by Karl Kesel, and a run on Thor written by Dan Jurgens. Wade inked one of those issues, I think, and Scott Koblish did the rest. Scott is incredibly talented, and 100% got what I was trying for on Thor. He inked the Hulk story too, which was in a very similar vein. As for Bruce, any time you get to work with a writer who is also an artist, it just makes the job so much easier. Half the penciller's effort goes into problem solving at the best of times, but a writer who understands visual storytelling will never put you in a corner.

After Secret Identity, how did you end up at Marvel and specifically working on Ultimate Fantastic Four and Ultimate X-Men?

After the Hulk, Axel Alonso offered me an exclusive at Marvel. I think this was swimming upstream a bit, since, as I understand it, there was a perception in some camps that I was suited more to a "quiet" kind of superhero story, not necessarily "Marvel style," never mind that I'd already been working for them for years. That comment proved useful, though; in 2003, Wade and I illustrated a Pirates of the Caribbean story for Disney Adventures, anticipating the movie, and I elected to open up the drawing for color – a complete turnaround from the shadowy work on Thor and the Hulk. Working on a kids' humor comic also permitted me to exaggerate expressions and movement. It was a lot of fun.

The job I was supposed to have done under the Marvel exclusive had to do with Iron Man, but for some reason it fell through. I got assigned to Ralph Macchio's office instead, where the Ultimate Fantastic Four creative team of Millar and Kubert were disbanding, so Warren and I picked up the reins. I tentatively tried out some techniques I'd enjoyed on the Pirates story and nobody complained, so I kept it up.

The Ultimate Fantastic Four arc ended in a mad scramble with only a fragment of a script and assistant editor Nick Lowe and I brainstorming plot points on the phone as I drove cross-province to a wedding. Issue 12 credits Warren and I as “storytellers.” It wasn't an ideal situation, but it cemented a lifelong friendship with Nick.

Ultimate X-Men followed. My understanding was that Brian [K. Vaughan] was not as keen on the cartooned style as Warren was, but I enjoyed myself.

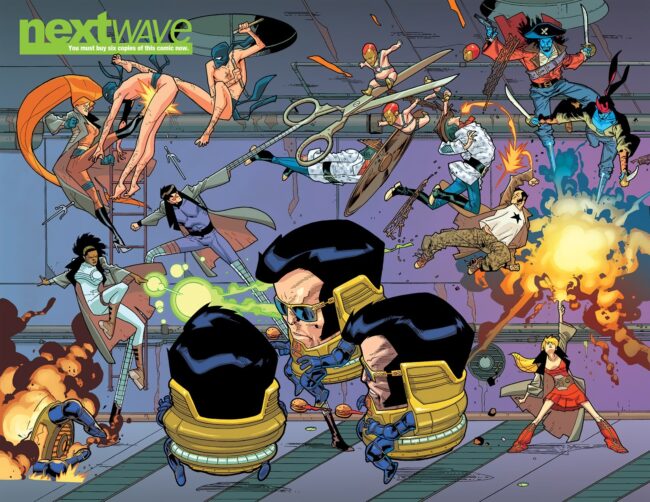

You and Warren Ellis clearly got along somewhat because after Ultimate X-Men, you two made Nextwave. Or did you get along?

Warren and I to this day have never spoken, and in the last fifteen years have only exchanged a handful of emails, so there's virtually no sample size from which to say we get along or don't.

It's true I was irritated at how Ultimate Fantastic Four ended, and when Nick called to ask if I was interested in Nextwave, I had serious reservations. The convincing factors were that Warren had already written the first few scripts – on spec, I believe – and that they were brilliant. I also got on so well with Nick that I knew he would have my back if it went sideways.

What were your thoughts and conversations with Warren like early on, especially as they relate to the style and the tone of the book?

Well, this is the thing. There was no discussion. At first, I reached out whenever something was not 100% clear for me, and the response was always, "do whatever you want." So I stopped asking. And in fact, this proved to be such an amenable way of working, I used it as a template for collaboration going forward. Compared to working with writers who want to argue over polishing mushrooms, or who telephone from the bathroom because they have a few minutes to spare, this was an unfettered pleasure.

The average layperson doesn't understand the collaborative process in comics well at all; in most cases, it works best when there's some latitude for decision-making all down the line, at least, when everybody's being professional and working to capacity. Trying to exert total control benefits no one and hampers creativity. I had had the impression that Warren was a very hands-on writer, but in my experience, it was strictly arm's length which ended up suiting me very well.

So all my conversations were with Nick, who basically supported every decision I made. There were a couple of missteps on my part early on, as I misread Tabby and Elsa's personalities, but once we sorted that out, the watchword was anything goes. Nick and Warren both liked the anime FLCL as an influence, but I tried to watch it and didn't get it at all, so I just struck out on my own, refining the stylistic ideas I'd been using on the Ultimate titles. I think Kathryn and I were also doing Never As Bad As You Think around 2005-2006, which was possibly more cartoony and silly so in a way Nextwave seemed comparatively conventional.

The book was funny and over the top and you used a cartoony style for it, but for a book like that, are you thinking about how it’s supposed to be funny? Or is that more about the choices you make at the beginning and after that your role is more about the storytelling and less what it means?

The book was funny and over the top and you used a cartoony style for it, but for a book like that, are you thinking about how it’s supposed to be funny? Or is that more about the choices you make at the beginning and after that your role is more about the storytelling and less what it means?

Well there's no comedy "set it and forget it" button. Yes, you can improve your chances by, say, designing a spaceship that's four submarines lashed together, or parodying a familiar costume or giving someone an absurd haircut, but sustained humour is 99% in the execution. There are conventions of comedic storytelling that an audience will recognize and respond to, just as there are conventions for romance or horror or any other genre. Look at Kirby's Dingbats of Danger Street and compare it to Young Romance and to Fantastic Four; they're all clearly one person's work, filtered through his vision, but still all different in approach. Not in the construction of the drawings themselves so much (though they were obviously created during different periods of his career), but in pacing, composition, expression, exaggeration and so on. A clown can be terrifying, this is a well-known fact.

Whose idea was that in Issue #10 as the characters are hallucinating and sent into these weird universes that you would draw each in a different style? And how did you decide how you wanted each to look?

Ah, that was Nick. It wasn't in the script, and to my shame, I didn't think of it myself. I picked four – was it four? – that I thought would look different from each other and different from "my" drawings, but in retrospect, I could have put a lot more thought into it and maybe made more diverse choices. I'm not sure how successful it was as a set of faithful homages – even the Elsa Bloodstone Hellboy bit was pretty weak Mignola tea – but it served the purpose of the gag.

There was a Legion story from 1999 which Paul Levitz wrote, I pencilled, and George Freeman inked which was a similar idea; a number of "bedtime stories" with different characters and different looks. I had certain illustrators or genre or period styles in mind when drawing, but I didn't communicate those to George, who did his own thing on top. I liked the result pretty well, but I think the original intent got diluted somewhat. Again however, latitude for creativity makes for happy collaborating.

Half of Issue #11 was six two page spreads, which essentially can be laid back to back. For something like that, what did Ellis write and how do you go about drawing it. Because it looks and reads incredibly – but I’m sure it was a pain to actually do

I don't recall exactly what the script asked for. I think Warren had a list of bizarre character suggestions which Nick augmented with his own ideas, and then there were oddball Marvel characters we were permitted to use as well. I don't remember if the videogame side-scrolling aspect was specifically asked for, but a long, stupid, fight-y Bayeux Tapestry was basically the idea. There wasn't a whole lot to the script except the callout captions and the lists, as I recall.

I know that the work that people enjoy reading isn’t always fun to make, but you really seemed to enjoy the bizarre aspects of the book. Was it fun to make the book?

Definitely. It was at the heart of a really fertile period for me, and, while I'd probably do a bunch of things differently given the chance, it was actually very satisfying in almost every respect, which is something I've not quite experienced since in my mainstream work.

I love the cover designs for Nextwave, which I feel are one of the more under-appreciated aspects of the series. What was behind these wild collage-y Photoshop designs?

I love the cover designs for Nextwave, which I feel are one of the more under-appreciated aspects of the series. What was behind these wild collage-y Photoshop designs?

Thank you. Mostly, it was just me goofing around with color and texture and Photoshop layers. After the first issue, I think Nick asked for each issue to highlight a certain character, but otherwise didn't provide much concrete direction. It was pretty remarkable to be permitted to design a new logo every issue, and to try out effects and palettes as whim dictated. The only constant was a 3:2 ratio of top to bottom sections, which got put aside for issue 11, the Civil War parody, which was instead plit 50/50. I was irritated well out of proportion to the ask, and ultimately, I was wrong, because of course it was funnier. The Black Watch tartan which replaced the Civil War black background may have been Nick's idea, or he suggested it not be black and left it to me.

A similar but opposite thing happened with the covers for Secret Identity – I hated the comicbook Superman logo in the color block behind the lowercase sans serif "secret identity" and made the block on the last issue black to thwart its use. I mean, I get it – you gotta sell books, but even at the time there were numerous exceptions – Superman For All Seasons, Superman: Red Son. I still hate it, actually.

So why did the series end at issue #12?

The usual reasons, I guess. I mean, whatever publishing algorithm was in use at the time didn't project future sales meeting expectations. Also, I don't really know Warren, but from the outside, it seems like he's a serial comics monogamist, throwing himself behind whatever's interesting at the time, and then moving on, which I respect.

Twelve is a good number, I think. It makes a satisfying chunk of a collection that is perennially accessible. Nextwave is a good-looking corpse that died young.

Is there any chance of you and Ellis working together again?

The whole interview just landed on the head of a pin, didn't it? Four or five years ago, Nick, Warren and I batted something around as a one-off. I think I suggested an idea about Aaron Stack being a trojan for H.A.T.E. which the others liked OK, but we couldn't coordinate schedules so it fell apart. Then, just last year, Nick floated a possible reunion for Marvel’s 80th I think, but again it went nowhere. All parties have really moved on at this point. I don't even think working on an entirely different project would happen now.

When I ask if you “got along”, I’m not asking, did you hang out and talk on the phone a lot. When people work together on multiple projects, the assumption is that you work together well – or work in a way that’s compatible. Which usually means there was no micromanagement and a lot of trust. I’m sure anyone can point to exceptions in their careers, but I think that’s usually true?

I'm not sure. It definitely works for me. I'm comfortable in my wheelhouse and believe I have demonstrated an ability to work to a high standard unsupervised, but I'm not convinced this is the default way to work, even for independent freelancers. Kathryn and I were just talking about the isolation-induced phenomena of increased efficiency that people who are not used to working from home are now experiencing, owing to fewer distractions than in a conventional workplace. The tradeoff of more interruptions when working in a studio or in close collaboration is immediate feedback and social interaction, which – uh, hello, mammals! – most people benefit from. For me, it generally gets in the way of finishing.

On the whole, I've worked with more writers who prefer input – asking for anything from favorite characters to use to actual story ideas – than not, and lots of artists want to facilitate that and enjoy it. Some smart ones spin this into writing careers of their own. However, I feel like the job already entails plenty of unpaid and uncredited work—characters, costumes, environments, creatures, props, logos, user interfaces and so on all need designing for example – if I wanted to write as well, I would write. I should stress though, that I don't think these requests or offers come from a place of laziness or a desire to exploit; I rather think the default collaborative model involves more give and take than I'm willing to participate in. So in this respect, Warren and I got along great.

I know how well – or, to be precise, not well – the book sold. But are you aware of how beloved that book and your work on it is?

Well, I don't think sales were ever bad, they just didn't set a fire under the marketplace. A book that sold Nextwave units today would be a keeper, sadly. But more to the point, um, I guess yes? I know the book still has cache and benefits from a lot of word of mouth. "Beloved" is a word that makes me very uncomfortable, however. Sometimes people at conventions will be very enthusiastic in their appreciation, which as a generally asocial person I find slightly alarming, but I smile and nod and thank them and am honestly grateful for it. But half the time, I don't actually remember what happened in that person's favorite issue. This sounds terrible, and I admit it as a personal failing, but I've also drawn tens of thousands of pages, and it is rare for them not to all run together in my mind, assuming I recall them at all.

As you know, I have had a lot of conversations with comics pros over the years, and many have mentioned you as an artist they admire and Nextwave as a book they cite. And I know lots of readers who loved it when it was being released and to this day. So I’ll argue for beloved. We don't have to get along to do this interview, Stuart!

No, no, it’s fine. Of course this is very touching, and I take it in the spirit in which it's offered. I'm seriously grateful to have had the good fortune to have maybe once caught lightning in a bottle. At the same time, after a long career filled with projects that felt more personally significant, I can also say I understand when Alec Guinness said he shrivels inside each time Star Wars is mentioned.

Fair enough.

You mentioned that you were making Never As Bad As You Think and Nextwave at the same time, which is pretty crazy. How did Never As Bad As You Think come about?

I followed a community/site/blog called Illustration Friday, which offered a weekly single word as a prompt for participants to create themed drawings. As far as I knew, no one was using it to create sequential comics, but it seemed to be a challenging and interesting way to develop – or let develop – a story. Kathryn and I decided at the outset on a “lateral” plot in the manner of Richard Linklater’s film Slacker, and we worked out a few minor additional rules (the script had to fit on a sticky note and there had to be four panels, as I recall) and we posted results to our own site as we finished each strip. Working against constraint as in, say, OuBaPo or within the formality of kishōtenketsu, can actually be a very freeing exercise, and the time demands were fairly slight in the end. We published it ourselves as a little postcard-sized perfect bound collection, and after a bit, Mark Waid and Ross Ritchie conference called to ask if Boom! could do it as a hardcover, which sort of took us aback, as we didn't think there was much to recommend it for a real publisher. I don’t even know how they heard about it.

Was this the first time that you and Kathryn had worked together on something since Playground/Headcheese?

No, not really but a lot of what we did together through the 90s and early 00s had limited exposure, or none at all. I mentioned a Captain America short which preceded Secret Identity, and either just before or just after that, we'd done an issue of a licensed property called Mutant X for Marvel. There was a job for a popular 90s movie franchise which went totally pear-shaped and never saw the light of day – I never even got paid, though she did – and some other short things here and there. Two stories for anthologies featuring a character we created named Jeopardy Jones. All short projects. Never As Bad As You Think lasted a year, which felt like a very long time for readers to bother with, but establishing the discipline to carve out time for a personal project in a busy work schedule proved worthwhile.

There's a way that the project really feels like play. More so than some other projects just because of the tone and the subject matter, but when you and Kathryn work together you do enjoy doing something different each time and playing around with how the story gets told, and just finding a way to make it not like your day job – even if it is also your day job. If that makes sense.

Yeah, absolutely. Primarily, we just get along wonderfully well, but also, "a change is as good as a rest," right? It works different parts of your brain, you engage with the medium in different ways, and hopefully, when going back to mainstream work, you can use that different way of thinking to avoid relying on rote solutions to storytelling or graphic problems. We ran a local comic jam at that time too, and it was really eye-opening to see how other people worked with imposed limitations.

How did you manage to carve out time for these personal projects? Because that’s not easy, and it’s something you have done that pretty consistently.

Just will power, I think. We talked about doing something longer frequently, but I was in the fortunate position of having plenty of paying work, so increasingly finding a block of time dedicated to making our own comics was more difficult. The idea of pacing out a work of some length over many weekends only gradually came into focus as a means of production when we found that Never did not interfere with either other work or personal life. Not much, anyway. Part of that, surely, must have been the episodic nature of the strip, which – having no conventional linear storyline – could have ended at any point. Moving Pictures required quite a bit more discipline and planning, but that was why we serialized it online as each page was completed; if there was an audience waiting – even one person – we would feel obligated to finish. As it turns out, that audience number was probably not far from the truth.

Did you and Kathryn go from NABAYT to working on Moving Pictures?

I think basically right away. I'm trying to remember exactly, but I guess there was probably a short gap in between. I think at the 2007 TCAF, we had the tract-sized copy of NABAYT and an ashcan of Moving Pictures for sale. I'm looking at archive.org now. Never was on Joey Manley's Webcomics Nation in 2006, along with some other strips of mine; a diary comic and a strip based around the avatar I created for 50 Reasons To Stop Sketching. By 2007, the site capture's a garbled mess, but if we had the ashcan at TCAF, then Moving Pictures was up and running in early-to-mid 2007, which meant it wrapped some time in 2009, when we started shopping it around to publishers. Top Shelf put out the book in June 2010, ten years ago last week, actually.

I think I must have imagined we were running some kind of webcomics empire-- why have four strips running at the same time? Distressingly hypomanic. As I recall, there was a flexible paywall system you could employ at Webcomics Nation, and we had some strips freely available and Moving Pictures behind a subscriber wall. No one ponied up, so midway through, we ported MP back to our own site, which was all hand-coded by me. I can't imagine doing even half of that now; managing multiple online platforms, dealing with printers, traveling to shows, drawing five comics at the same time. I probably shouldn't have done it then.

Who was this character Jeopardy Jones?

Oh, Jeopardy. Brian Clopper, who's an author and a teacher, spearheaded a couple of educational comic anthologies in the early 2000s; one was called Brain Bomb and the other was Imagination Rocket. Kathryn and I did strips in both featuring this very clever boy Jeopardy. In one, he explains pinhole photography to a goldfish and a nautilus, and the other was a lesson in friendship involving a loaf of bread and a squirrel. Kathryn also wrote a book-length story about Jeopardy and a new moon which I never found the time to draw, and which is a regret to this day. There were a couple of attempts to make it happen with other people, but it ended in a shambles. I think it's now wrapped up in too much sadness and will never happen, which is awful.

I think Jeopardy would be a great book, but I think it could only happen if we were repped by a literary agent who would get it in front of the right publisher, but honestly, the idea of involving other people in our endeavors is just not something either of us understand well at all, even though it might make good sense financially or success-wise. In many ways, we have not changed our business model since Playground; create the story, make the object in small multiples and hand-sell it to the consumer. Set one aside to mail to Factsheet Five for review. It's so small scale. It's fantastically exciting when you're starting out, that two or three hundred people are willing to pay money for your thing. The mechanism that would enable the electron shell jump in reaching a broader audience is something neither of us have the stomach for.

The two strips we did make were good, though. One (both? I don't remember) made it into Centifolia, the sketchbook/comic collection we put together. It also occurs to me now that Moving Pictures is probably the only comic we've done that doesn't have talking animals in it.

So after Nextwave you took over drawing Ultimate Spider-Man from Mark Bagley. How did that happen?

The usual way – I got a phone call. I was working under an exclusive with Marvel, and they were obligated to feed me work. Once Nextwave was on the chopping block, contractually something else had to take its place. I don't know if there were any discussions as to creative compatibility, except insofar as both books were under Ralph Macchio's aegis as Ultimate editor. I guess Mark leaving was a known quantity and they needed someone – preferably someone whose track record they knew – to take his place. In my experience, editorial decisions are usually as matter-of-fact as this.

When you step onto a book like that, which had been going for almost a decade and was a “Bendis-Bagley” comic, are you thinking about or approaching it differently than comics which were visually defined by dozens or hundreds of artists?

As you say, long-running series are like relay races; the baton is always being passed at some point or other, so Ultimate Spider-Man was unique in that it had had a single collaborative creative voice for its entire existence. I think I probably suspected that even if I had tried to emulate Mark there would be a negative reader reaction, so I figured there would be very little point in attempting such sleight-of-hand. I just did me, and generally speaking, people hated it, and still do, if Reddit and Twitter are to be believed.

As a rule my process does not involve a lot of prep work – yet another failing on my part – so there usually isn't a period of consideration or refining of ideas or approaches. I just start. I even balk at thumbnail layouts for pages. It's stupid, really, and I pay for it later with lots of erasing when my initial instinct does not pan out. But the idea of doing something twice sticks sideways in my throat something awful. I see the amount of labour that goes into, say, film or video game production design – ten or fifty or a hundred ideas going to waste for every choice made, and I know it's something I could never do. Comic making is just on such a different economic scale, and the deadlines are so tight, even if I was the kind of person who wanted to fuss, there isn't time. And my work is not really of a quality that readers and editors would wait for, anyway.

So you don’t layout at all? What is your process exactly? And how has that changed over time?

I may have overstated. I do prepare thumbnails but they are very rudimentary, just the panel arrangement and some vectors or crude shapes indicating the main masses in the panel. The great bulk of the work happens directly on the page. I've said in the past that this preserves a certain energy that would otherwise be lost scaling up a more comprehensive composition from layout. When it works, this is true. When it doesn't, there's a lot of erasing and hair-pulling and frustration.

The method hasn't really changed over the years. It works well enough for me to just roughly block out the dominant features in the planning stage. Poses, lighting, depth of field, leaving room for dialogue, can all happen on the page proper, and I honestly feel that -- for me-- it's better if they do. I start very loose with non-repro blue pencil, and refine and refine and refine until it's done. It's not magic-- I think this is probably how 80 - 90% of illustrators work. After all this time, however, I still struggle with the same problems; my compositions tend toward being too symmetrical when they should have more tension or imbalance; I find that I either over- or under-fill the space; hair is hard to draw.

I like your work on Ultimate Spider-Man and I’m sure some of criticism/dislike is simply you weren’t Mark Bagley. It sounds like you knew that would be a response going in and just decided to do your own thing and trying not to second guess yourself.

Second guessing is half my work day! But yes, really, that's true, I was prepared for a negative reaction. And thank you. I'd like to imagine that I took it on the chin a bit for David and Sara – that after my run, readers might be more accepting of artists other than Mark if I took the brunt of their ire, but of course, that's ridiculous and everyone gets their share of fans and detractors. I personally think they each brought a clarity of vision to the character that puts my scrawling to shame, but they don't need me to say so. They're both brilliant.

How did you and Bendis work together? Because you did work together for about a decade.

I hadn't given it much thought until now, but you're right. Ten, twelve years on and off, I guess. As to how – it was much the same as with Warren, really. Very hands-off, which I suppose was my choice. I wasn't aware of how hands-off until we met in San Diego in 2010. I approached Brian and started chatting with him but didn't bother to introduce myself, assuming he would know my face from Twitter or whatever. Once I noticed he had that look like I might be a stalker who knew all his personal details, I realized he had no clue who I was.

My main point of contact on Ultimate Spider-Man or Avengers or X-Men was really Nick or Tom. Working with Brian was always easy. I liked the balance of humor and action, the character stuff was fun to draw, sales were always good. Eventually, I walked away from All-New X-Men because of scheduling. The book was being published sixteen to eighteen times a year which worked for Marvel's financial model, but meant more fill-in issues than I would have liked, which diluted my visible contribution even though I was working on it 52 weeks of the year, regularly hitting what would be monthly deadlines in other circumstances. For years I stumped for work on a "boutique" title I could lay more claim to, but apart from a short run on Captain America, my value to the company lay in making other kinds of stories.

As far as working with Bendis, you guys went from Ultimate Spider-Man to New Avengers to All New X-Men. How did you end up going from one to the other? Was it just what they asked you to do? Did you lobby for any of them?

I was offered the jobs as they arose. I don't know the behind-the-scenes circumstances why, but the usual scenario seemed to be that another artist was leaving, Brian and I got on well enough and Tom and Nick knew I was reliable. In other words, I fit the shape of an available slot. I wasn't aware of the jobs before they were brought to my attention, so I wouldn't have known to ask for the opportunity, if you see what I mean.

Also during this time, you drew the Fear itself crossover. How did you end up on it?

Tom called. I knew Matt and I liked the pitch, and not to be too mercenary about it, but I thought it would be dumb not to take the offer for a book that would get a big push. It's not like you're ever given a buffet of choices. An editor contacts you and you can drop what you're doing and make a lateral play, or you can stand pat. Keep the silver tea set or pick what's behind door number two. There's no wrong answer. Or rather, there's no way to know if there's a wrong answer.

Having drawn a company wide crossover at DC years before, how did Fear Itself compare?

It's a fair question, but I'm not sure I have a solid answer. Final Night was four compactly plotted regular sized issues. The story had short-term repercussions in various other DC comics, but they weren't intimately tied to the core book, and readers didn't have to read everything to understand our story. Fear Itself was more than twice as long, with characters and storylines spiraling out into other titles. But those aspects didn't really affect my work. I think I'm probably like most comic artists in that my main concern is not at the macroscopic level; I'm thinking about shaping at most a single issue at a time, how a sequence of panels can best serve the story, which composition or expression most effectively sells the intent of the script. The fact that it was a crossover or event was less of a focus for me than making each issue, each page as good as possible, one page at a time. In retrospect, I'm not sure my contribution lived up to expectations. Wade and Laura did stellar work.

George Perez and others have joked/complained about the complexity of drawing team books and crossovers and all that that involves. You’ve drawn a lot of team books and solo superhero books. What do you think?

Really? I'm surprised, given George's body of work and what little I know of his methodology. But yes, it's generally a hassle, but it can be fun, too. The action stuff is usually not a problem – chaos and rubble everywhere comes together fairly organically, and there are lots of ways to arrange the pieces to make it work. It's the quieter scenes with lots of dialogue which cause trouble. It's a challenge to arrange characters without making them look like a stiff police lineup, to give everybody face time and be consistently in the right order while sitting around a table over many panels, to make the figures individual and the body language nuanced and natural. Fighting characters are just dynamic geometry, pointing obliquely or smashing together. Characters talking in a room have to be human, which is far more difficult.

A lot of the comments tends to be that it’s more “work” because one has to squeeze a lot of characters into panels, and have less options as far as composition and design just because of all that.

Yes, all that's true, but when there are fewer choices it can be easier, faster and more direct work. A nine panel grid often actually goes much more smoothly than three or four panels on a page. You can just get on with drawing instead of worrying if it's pretty enough. I enjoy drawing backgrounds, but they are time consuming. As to George, my understanding -- mostly via Kurt-- is that he's an obsessive noodler, and will add characters and detail even when they're not required. I could be wrong.

So you don’t feel the need like Perez to constantly add characters and details everywhere? What did Will Elder call it, chickenfat? Or whatever the superhero equivalent would be.

That Elder comment is brilliant – I hadn't heard that. No, I guess my tendency is to land on the other side of that fence but without the compositional intuition of say, a Paul Grist or a Mignola. I struggle with striking a balance between providing not nearly enough and just chaos. There's a delicate middle ground where there's just enough thoughtful featherweight frill in a drawing which elevates it without being overwhelming, and I don't feel like I have the touch for it.

You mentioned that you had wanted to work on a boutique title where you had more creative control. It sounds like the way scheduling changed, with 18-24 issues a year, that just wasn’t a possibility.

Well not all titles are treated the same. The accelerated schedule was not applied across the board, just as there are, say, multiple X-books but only one Black Widow. Again, Captain America filled the brief pretty much, but for various reasons, it was only one arc.

You did have a pretty high profile few years where you and Bendis relaunched New Avengers, you drew Fear Itself, you and Bendis launched All New X-Men, and then you and Remender relaunched Captain America.

Also during that period, Mark Waid, Marte Gracia and I launched Marvel's digital Infinite Comics line. It's funny, but globally, the one project that eclipsed all these put together, that sold more copies and was seen by more people, was a two page story that Kathryn and I did for Astérix et ses Amis, a tribute album for Albert Uderzo's 80th birthday. It's virtually unheard of in English-speaking North America but it’s been printed in a hundred other languages.

I've been extremely fortunate, there's no question. I'm not sure how, or even if, I've earned this position, but I'm grateful to have been afforded the opportunities I've enjoyed and have tried to pay that forward.

You must know the aphorism that posits that a freelancer can be talented, fast or easy to work with but needs to be two out of the three to succeed? Obviously there are more challenges and barriers than that, and the playing field is far from level, but knowing that there's not much to be done about natural ability, I've spent a lot of time working on improving the last two qualities in order to ensure that I've had currency in a changeable market. I also just as often feel like a record store clerk who got very, very, very lucky.

I’ll be honest, I did not know that you and Kathryn worked on Astérix et ses Amis, so clearly I’m one of those clueless English speakers. How did that come about? Are you a big Asterix fan?

Yes, we both read Asterix as kids. I don't recall who the intermediary who made the introduction was, but Sylvie Uderzo was looking for international authors to round out the book of mostly French cartoonists. David Lloyd did a piece, and [Milo] Manara as well. Our story was about Dogmatix and a bunch of other talking animals. In the end, there was a issue with attributing credit consistently across the editions which tainted the project, but I'm pleased with our contribution.

How did you get the Captain America gig? And why did you only end up drawing six issues?

Again, it was a phone call from Tom. I don't know if the offer was intended to address my desire to do a solo character story, but it did fit that brief. I wasn't that familiar with Rick's work, but I liked the pitch and thought that the proposed story felt significant enough to have a long shelf life; a re-establishing of Sam Wilson's character and history for a contemporary audience. Being able to continue to work with Wade and Marte was also a huge benefit.

The relatively short stay on the book was all on me. There's always a learning period when you start working with a new collaborator, so you need to be flexible going into a fresh project. As with Brian K. Vaughan on Ultimate X-Men, I had a feeling pretty early on like I wasn't giving Rick what he wanted, which was very disheartening. He's a really visual thinker with a background in animation which is an enormous gift to a comic artist. As a result, he had very specific things in mind in the script, and I felt strongly that I wasn't able to deliver on all of it, and was therefore letting his vision down. I was prepared to step aside on the gig, but Tom convinced me to see the arc through to the end. I'm glad of it actually because I redoubled my efforts and I think it ended up being a very strong story. I hope Rick thought it was okay, but to be honest, I really don't know.

One reason I keep asking about the circumstances of Marvel books is just because I want to destroy our romance of the industry.

Ha!

Seriously though, you were under contract with Marvel and it sounds like they asked every year or two, do you want to stay on this book or draw that book? And you tended to say, let’s try something different.

Well, on the Marvel side, that was pretty much it. I can't speak to the exact reasons why behind each offer but they were paying for my services and would obviously want to maximize their return. And I definitely tended to seek higher ground. Because it's a new shiny thing, or appears like it might be a smart career move, or offer creative opportunities. Staying in one place longer might have been more ideal had I wanted to cement a "legacy" in the way you think of certain creators coupled with certain characters or titles, but that's not the path I chose. I may have been wrong. Could have just been restlessness. Chronic frustration with my own limitations, probably.

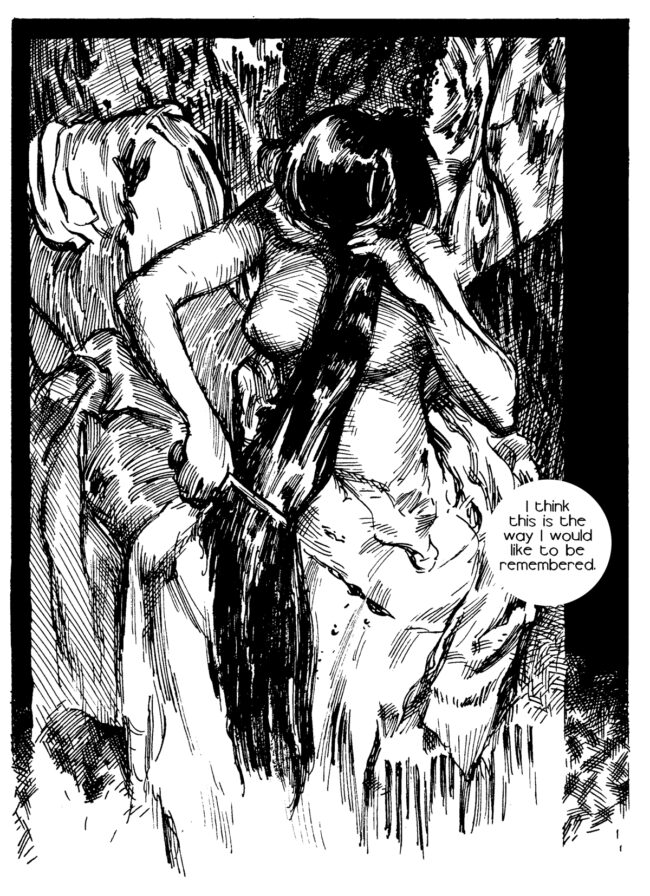

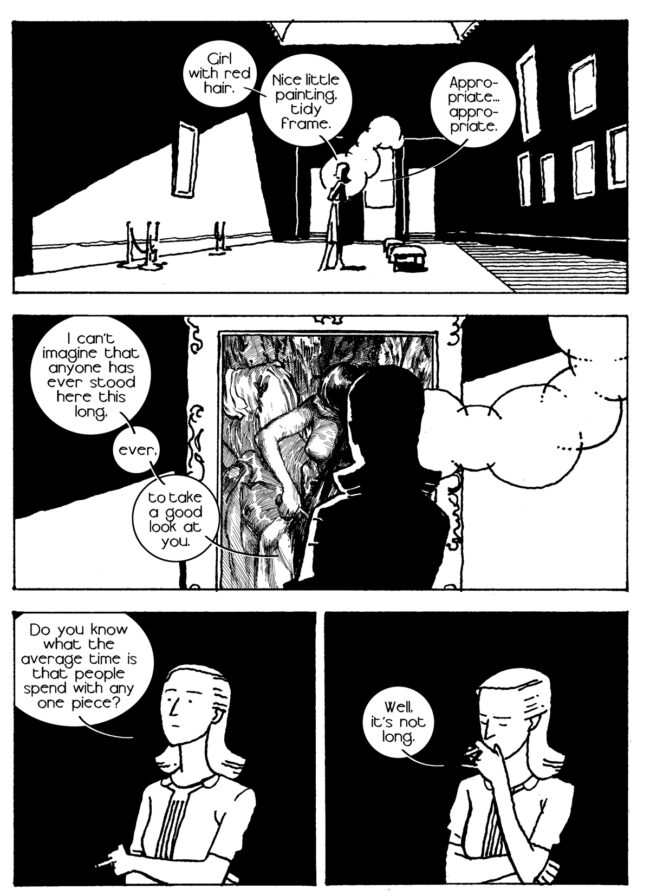

How did Moving Pictures end up being the next project that you and Kathryn made after Never As Bad As You Think?

Kathryn had been reading Janet Flanner's 1940s Paris correspondence originally published in The New Yorker magazine, and had been particularly struck by a breezy comment about how acquisitions in the Louvre had been getting a better cleaning in wartime than ever before. She drafted a dialogue-only script loosely based on this inspiration, but it wasn't necessarily intended as a comic, or even something we might collaborate on, just a writing exercise. But I was looking for something longer for us to do, and convinced her that it could work. I didn't want to ask her to concoct something fresh as she had other obligations. In short, it was the next thing because it seemed a shame to waste the effort already put into it by leaving it in a drawer.

I also knew it would be a long haul if we modeled the schedule on how we had done Never; evenings and weekends, one page a week. It took a couple of tries to come up with a drawing style that I could recall readily and consistently for a few years after spending the work week doing mainstream comics.

There are so many deliberate choices you made in that book. From the linework which makes me think of an artist like Michel Rabagliati, to your take reproducing various artwork, to the way so much of it is about depicting stillness, to avoiding obvious ways to establish the time and setting. It’s sparse and really beautiful and I just wonder if you could talk about some of the thinking behind it.

This is a compliment of the highest order. I'm such a fan of Michel's. Paul Has A Summer Job in particular is a desert island favorite. There were other influences, European artists Stanislas and Ulf K. A little Jooste Swarte, perhaps. The stillness was deliberate, as was a regimented pacing, though it presented a particular challenge as to how to depict the one moment of violence – when Rolf throws a glass down on a table, shattering it. We used to say the only action in the story was when someone stands up.

Again, the initial line of thinking was that it had to be rendered in a way that could be picked up over and over after longer periods of doing other kinds of work, and to maintain consistency over many months. We agreed that the spare quality – the hard division between black and white areas, with little texture or feathering to blend the two – suited the tone of the story, or, perhaps flew in the face of it, depending on how you read it. There's a deliberate yin/yang balance of light and shadow throughout, except for the reproductions of the artworks, which are more...not realistically handled, but traditionally, I guess, with hatching and more line variety to indicate a spectrum of tones. As I say, it perhaps flies in the face of expectation – a story with some grey motivations being rendered in a blunt, cartooned black and white manner, interspersed with other artists’ images – flat in the real world, but in a way more real than the human characters.

Until the end, however, where there's a person-less depiction of an escape to a more hopeful setting, and then we return to Ila's world not much different than when we left. Now that I think about it, we did the exact same thing in Russian Olive to Red King, which actually put a lot of people off. "Avoided the obvious" is a fitting epitaph for our respective careers, cheers for that.

I thought you would be a fan of Michel Rabagliati. Paul Has a Summer Job and Paul Goes Fishing are two of my all time favorites. I’m constantly amazed he’s not bigger and more widely known.

Absolutely. It's brilliant cartooning. The themes and situations and characters are universal, it's funny and sad, so who knows why? But you're asking the wrong person if you want to pierce the veil of popular culture. It's pretty much a given that I don't like or understand stuff that is otherwise massively adored. I didn't like Knives Out. Or Parasite. Or Ford Vs. Ferrari. I suspect that Michel does much better in the French market. Just checking out Amazon.ca, Paul Has a Summer Job is ranked below 477,000 out of all books, but the French edition is ranked at just over 78,000, an order of magnitude better in sales. That's better than the trade edition of Marvels: Remastered!

I don't know. You tend to see the same names over and over in any kind of top ten list. If I actually knew what other people wanted for their entertainment dollar, I might have had a very different career. I've made my share of decisions to try and hitch my wagon to a star, but when I have come on to a series, sales have inevitably dropped. I recognize – even admit! – that I have positive qualities which have floated my career – mass market appeal is not one of them.

Was part of the appeal and the pleasure of Moving Pictures for you that after a week of working on some Marvel superhero book you had this very quiet and pared down story which required different muscles – and sometimes felt like being a different artist?

Well, it's all work, so pleasure is maybe not exactly how I would characterize it, but yes, being in a sense forced to think about storytelling, page design, and drawing style in a pointedly different way hopefully allows you to return to other, more familiar work refreshed. Ideally, you learn something new-- well, new to you-- and you won't necessarily rely on worn-out choices to get from A to B going forward.

After Never and Moving Pictures, what did you think about the page a week webcomics format? Or was that more about finding a way to get it out and push yourself to keep making it?