Comics and collage are homologous. Both are discrete, discontinuous, heterogeneous, and modular. Comics are collages of panels/images (and often words). The form can be rigidly gridded like the Western (European and North American) ones, or freer and more expressionistic like shōjo manga.

Artists with an appreciation for comics have been fascinated by this interconnection, such as Jess, Joe Brainard, Öyvind Fahlström, Guy Debord, Situationist International, Isidore Isou (and fellow Letterists), Keiichi Tanaami, and Bazooka Collectif (which created influential collage art for both the newspaper Liberation and comics magazines like Hara-Kiri in the '70s).

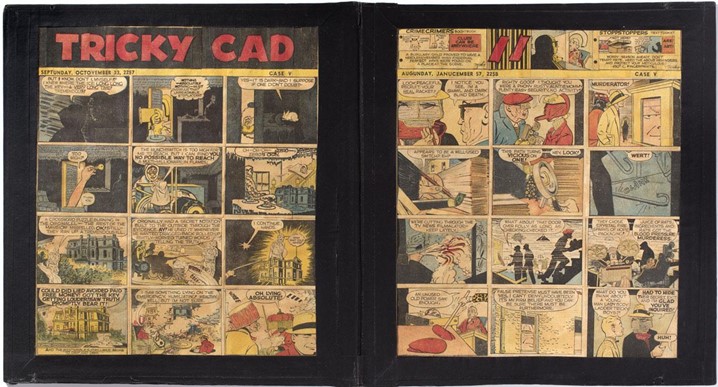

Tricky Cad (1954) by Jess

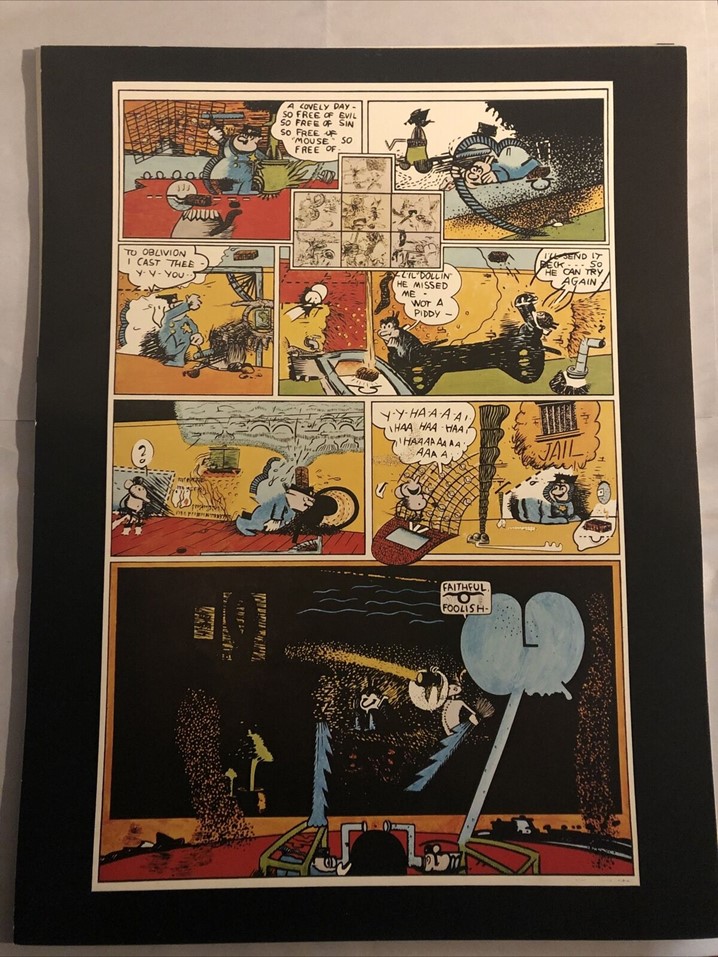

7 Roles: Une semaine sur l'océan and 7 Roles: Performing Krazy Kat (1961) by Öyvind Fahlström

Performing K.K No.2 (1964) by Öyvind Fahlström

C Comics (1964) by Joe Brainard

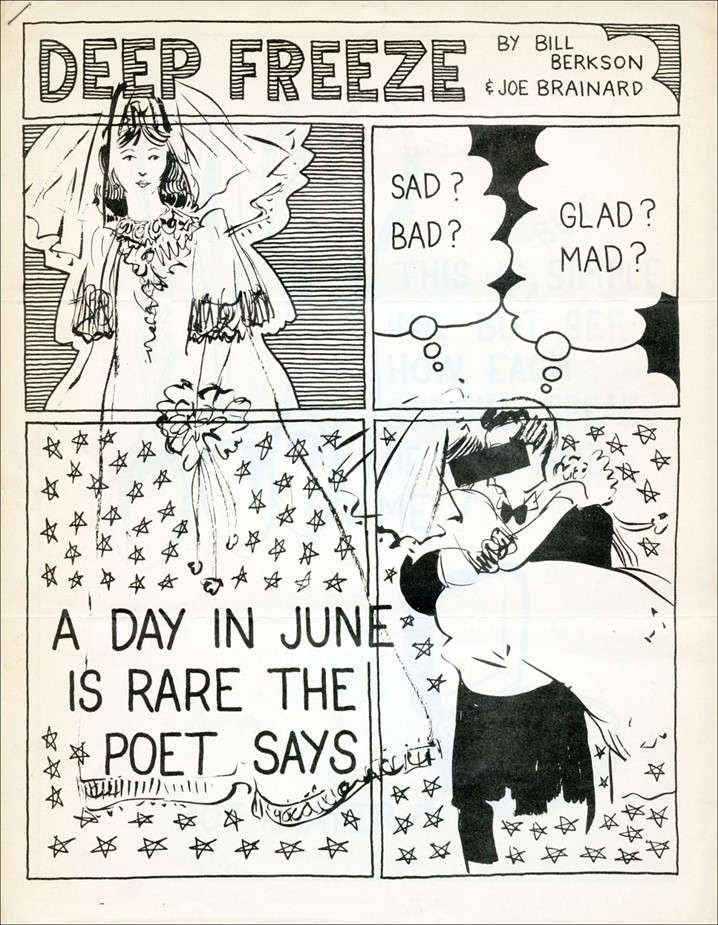

Deep Freeze (1968) by Joe Brainard and Bill Berkson

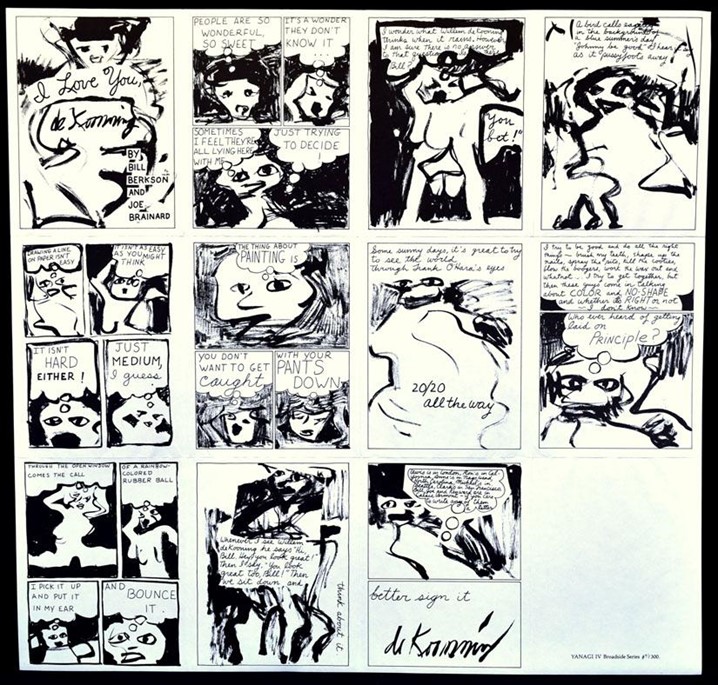

I Love You De Kooning (1977) by Joe Brainard and Bill Berkson

A Portrait of Keiichi Tanaami (1966) by Keiichi Tanaami

From “La creation ouverte et ses ennemis”, Internationale Situationniste 5 (1960) by Asger Jorn (Situationist International)

La Retour de la Colonne Durutti [The Return of the Durutti Column] (1966) by André Bertrand (Situationist International)

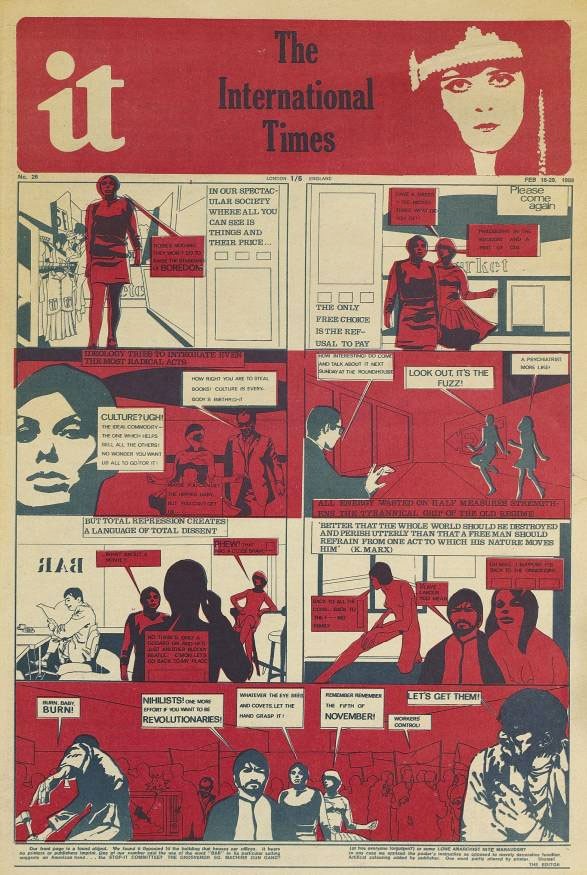

On the front page of The International Times (1968) by André Bertrand (Situationist International)

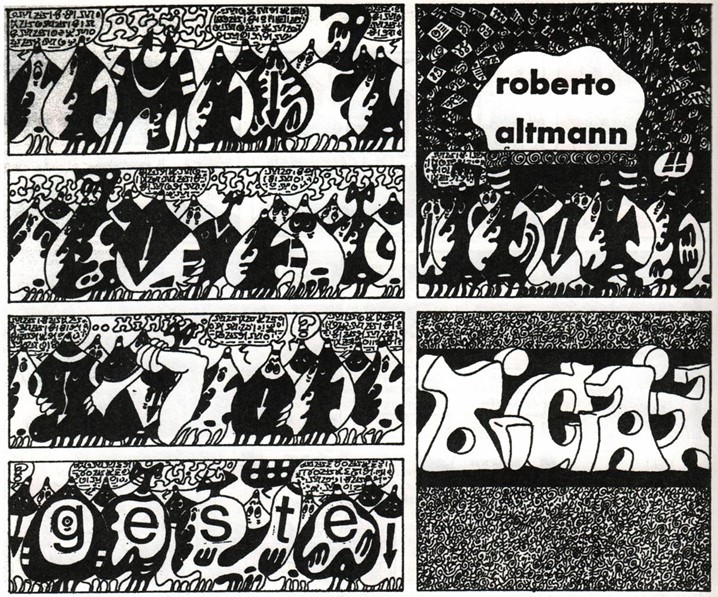

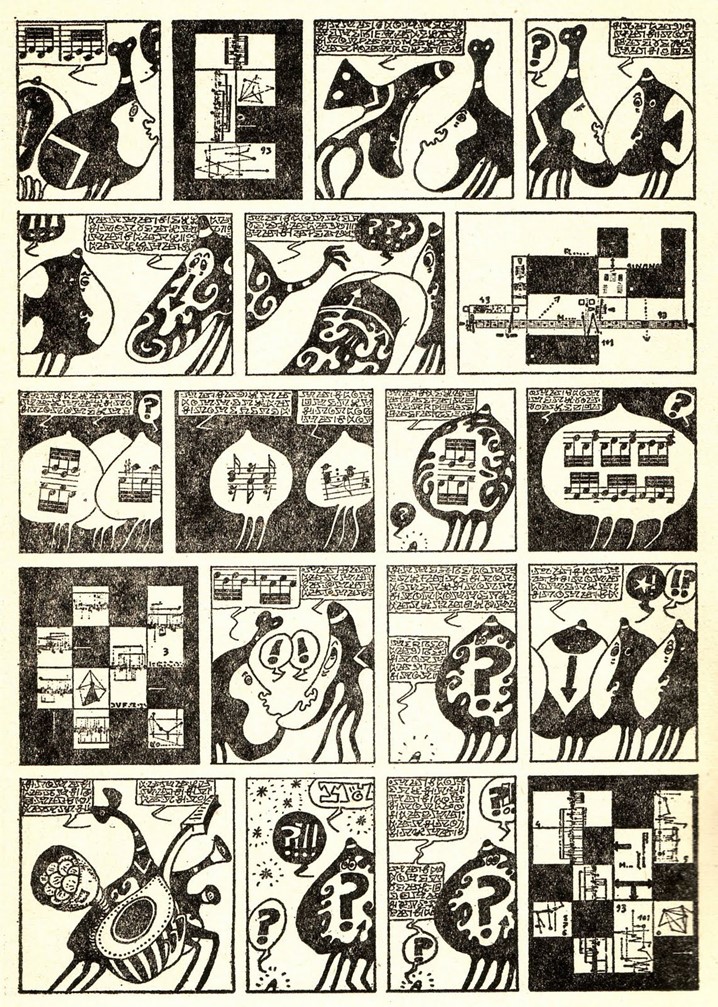

Geste hypergraphique (1967) by Roberto Altman (Lettrist)

Zr + 4HC1 → ZrC14 + 2H2U + 3F2 → UF6 (1970) by Roberto Altman (Lettrist)

In fact, the superhero genre is essentially a work of appropriation and collage; the same characters are rebooted (appropriated) again and again by different creators in different media. The identity of a character is a collage, or a database, of manifolds of characters. This working of superhero comics is similar to that of the oral culture such as legends, myths, epics, old tales, and sagas.

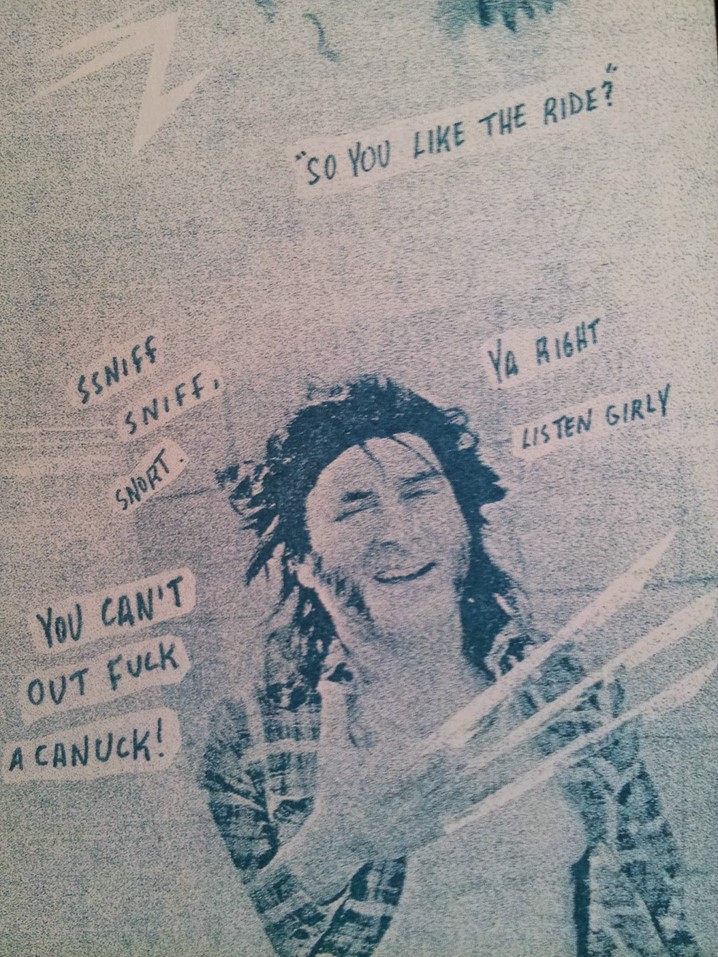

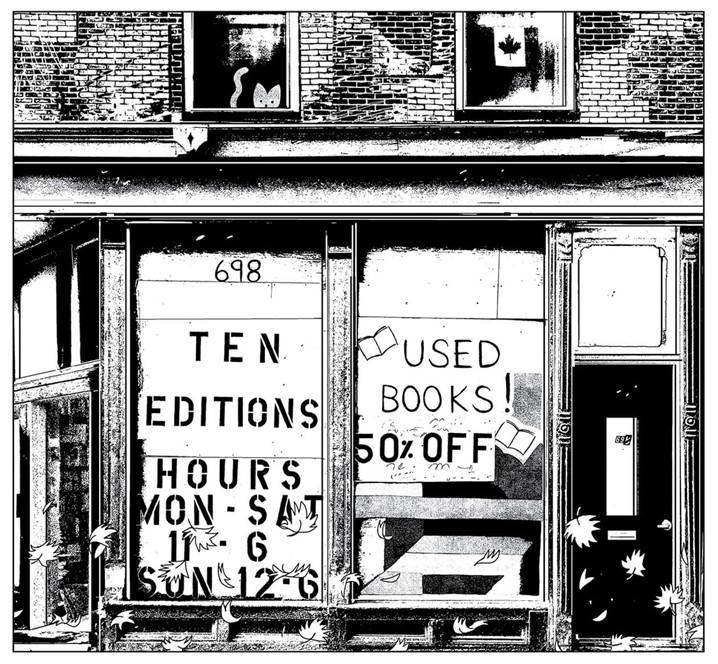

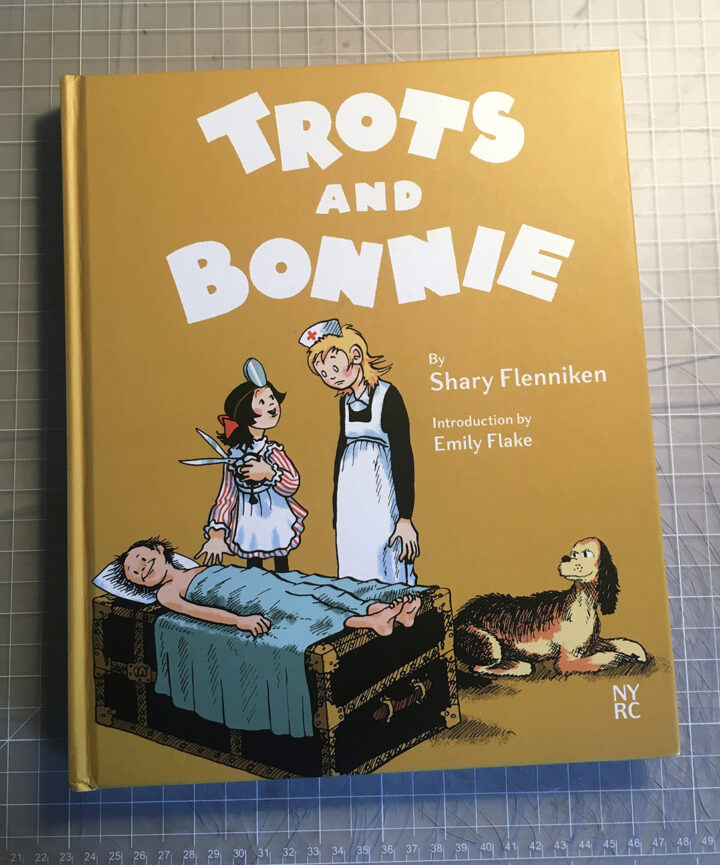

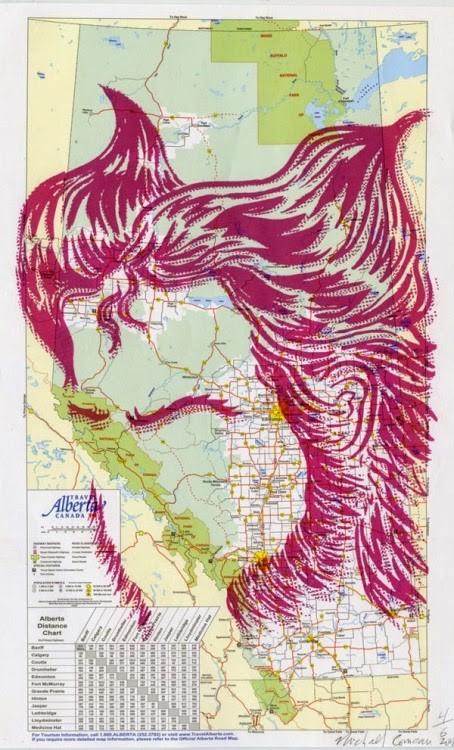

Michael Comeau’s collage/comics oeuvre explores this collage-ness of (superhero) comics in their form, style, and contents. The most illustrious example is Hellberta, which examines contemporary Canadian identity and history with various narratives and methods, including imageries and stories of Wolverine. The primary method of production is collage, but the deployments are various: a chapter made of drawings; a collage of Comeau's original photos; a collage of pre-reproduced materials; a collage of his sketchbook drawings; his characteristic silkscreen (Comeau created iconic posters for Will Munro’s Vazeleen club nights), which is a kind of collage with its layered method. Its narrative is also a collage: multiple threads of narratives are developed in parallel. They are not directly related, but as a whole, you experience Stephen Harper’s Canada through legends and tales of, for example, Wolverine. Finally, when Comeau collected three zines into a graphic novel, he switched the order of zines and pages: the collection as a whole is a collage too.

Hellberta (2015) by Michael Comeau

Comics and collage both operate in two layers: surface appearance (page) and the underlying source (panel). The ontology of component original images -- such as space, time, methods, and medium of the source images of collage -- disappears, and the new distinct ontology of the page -- such as spacetime or the narrative of comics -- appears. Guy Debord’s explanation of collage in A User’s Guide to Détournement -- “When two objects are brought together, no matter how far apart from their original contexts may be, a relationship is always formed.” -- applies to comics perfectly.

For example, Michael DeForge creates an imaginary city with edited photographs of Toronto in Leaving Richard’s Valley. The ontology of background in Leaving Richard’s Valley is the actual city of Toronto, but it does not exist in the real world. The synthetic reality highlights the cluttered urban space, and invents new meanings for both actual Toronto and virtual (synthetic) Toronto.

“This raccoon sculpture is a tribute to the Unknown Student, which sat in front of Rochdale College on Bloor Street in Toronto.” according to the Canadian monthly magazine The Walrus.

Leaving Richard’s Valley (2019) by Michael DeForge

Julie Doucet’s Carpet Sweeper Tales humorously deploys properties of collage -- for instance, the repeated use of original image -- and subverts the gender dynamics of photo novella, creating a medium of collage/comics and original material.

Carpet Sweeper Tales (2016) by Julie Doucet

Pakito Bolino collages, then re-draws it. The result is just a layer, not the two of a usual collage. The absence of the base layer (context) baffles the reader: the signifier and signified lose their meanings.

Spermanga (2009) by Pakito Bolino

The image inside a panel is also a collage. Bold lines distinguish every object from one another, especially the character and background. Comics’ flatness, modularity, discontinuity, and heterogeneity differentiate them from the continuous spacetime of contemporaneous visual media such as photography and cinema - and their great ancestor, traditional European paintings. The latter yearns for illusion and simulation of the real world, but comics are inherently representational. The latter lives in coherent continuous spacetime with a single definitive perspective, but comics are innately discrete. Comics artists have been exploiting this characteristic since the early days of comics. George Herriman’s background in Krazy Kat dramatically changes in every panel, but the reader does not perceive the discrepancy of the spacetime.

Krazy Kat by George Herriman

Patrick Kyle explores this collage-ness in numerous ways in his oeuvre. In Kyle’s works, space is “composite,” according to Lev Manovich’s The Language of the New Media. Instead of coherent space, a lot of distinct objects composite (i.e., are collaged to produce) the discrete and heterogeneous space. This outlandish space is a perfect fit for the non sequitur sci-fi nature of Kyle’s work. Space is not just a background, but the character and narrative. In Distance Mover, the composite space (collage) renders the space flat, thus making the textual (virtual) space and extra-textual (actual) space of the page parallel. Along with flat and surreal dialogue, the form and the content become congruent.

Distance Mover (2014) by Patrick Kyle

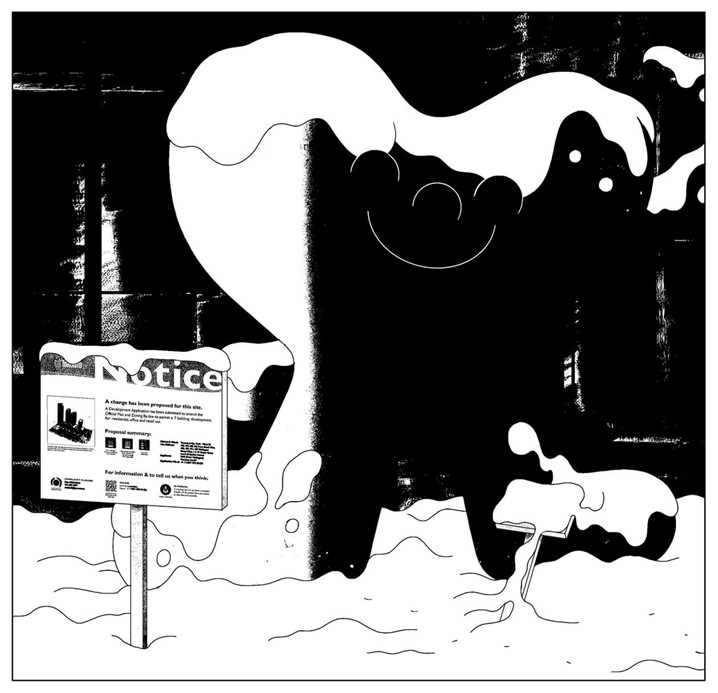

Eli Howey also utilizes the collage-ness of comics in their practice, such as Fluorescent Mud. It shows the sensation of bodily dissociation of oneself and the environment by hybridizing discontinuous and discrete objects and spacetimes that do not belong to one another.

Fluorescent Mud (2018) by Eli Howey

These two levels of discreteness, modularity, heterogeneity, discontinuity, and flatness demonstrate why comics are the medium well suited to collage/appropriation.

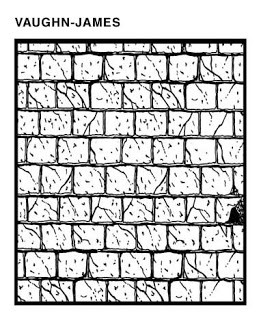

Mark Laliberte’s conceptual (comics) work BrickBrickBrick exemplifies this. Laliberte appropriated bricks from each artist’s work and “built” walls brick by brick.

BrickBrickBrick (2010) by Mark Laliberte

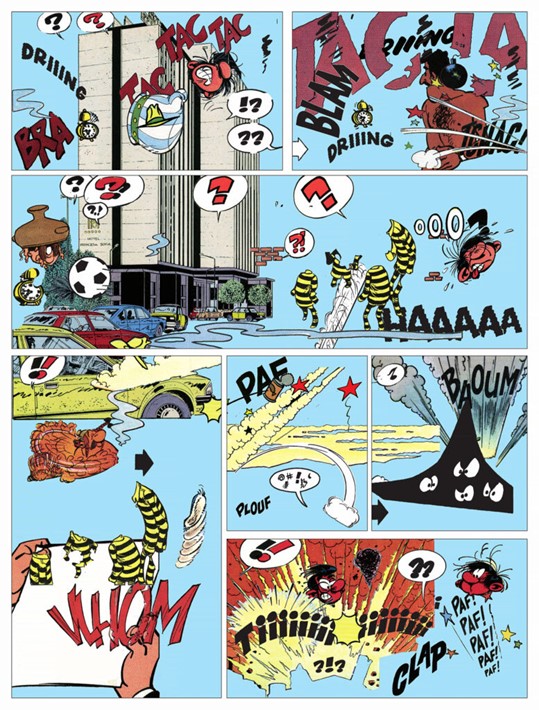

Compendium of Franco-Belgian Comics (2018) by Ilan Manouach

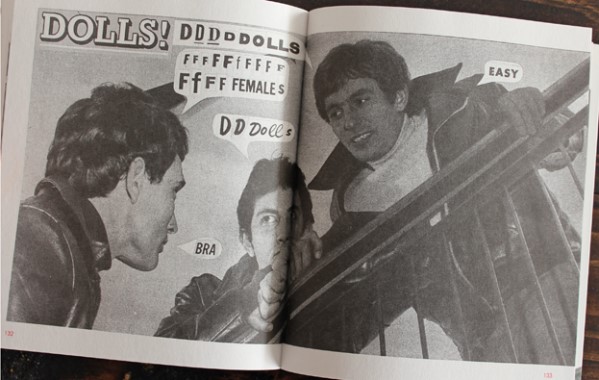

Francesc Ruiz employs appropriation to challenge the established social, political, economical, cultural orders, often that of heteronormativity.

Gary (2013) by Francesc Ruiz

The maturation of newspaper strips occurred concurrently with the Dadaist and Surrealist collages like Max Ernst -- whose work has been incorporated into the comics canon (e.g. included in 1001 Comics You Must Read..., edited by Paul Gravett) -- and beside Cubist and Futurist paintings. They were all part of the Modernist movement that rebelled against the European visual arts tradition of the single definitive perspective and continuous spacetime. It is no coincidence that Pablo Picasso created one of the first graphic novels Sueño y mentira de Franco [Dream and Lie of Franco] in 1937.

Sueño y mentira de Franco [Dream and Lie of Franco] (1937) by Pablo Picasso.

Mass reproduction was another important development that made both collage and comics possible. It is critical that comics were created in the pages of newspapers. Newspapers juxtapose stories in different spacetimes on a page. They necessarily have a modular design to carry these different stories. Grids come from this modular design, and might have influenced the panel-centric form of comics. The heterogeneous combination of words and images also follows from the newspaper graphic design.

The collage-ness of comics, i.e. their discreteness, modularity, heterogeneity, and discontinuity, enables diverse spatial possibilities in comics that differs from the linear, continuous, homogeneous, and cohesive, in both form and content.

I will explore how comics artists exploit these possibilities in the next installment.

* * *

Parts of the essay appeared in The Comics Journal #305 (Winter-Spring 2020); it has been revised and expanded for this online version.