She died on Wednesday, June 25, 2014. When I heard about it, I didn’t want to believe it. So I don’t. She was too full of life. Etta Hulme is an icon in editorial cartooning, a trailblazer for women cartoonists. She was a full-time editoonist on the staff of a major metropolitan daily newspaper before any other woman cartoonist was; she was widely syndicated at a time when no other woman cartoonist was. And she is also a treasure—short and gray-haired grandmotherly in appearance, witty and waspish in her opinions and deft in her drawing. I liked her a lot and admired her skill and talent, both as a thinker and as a cartoonist.

They say Etta died at her home in Arlington, Texas; she had been in frail health since a heart attack in 2009.

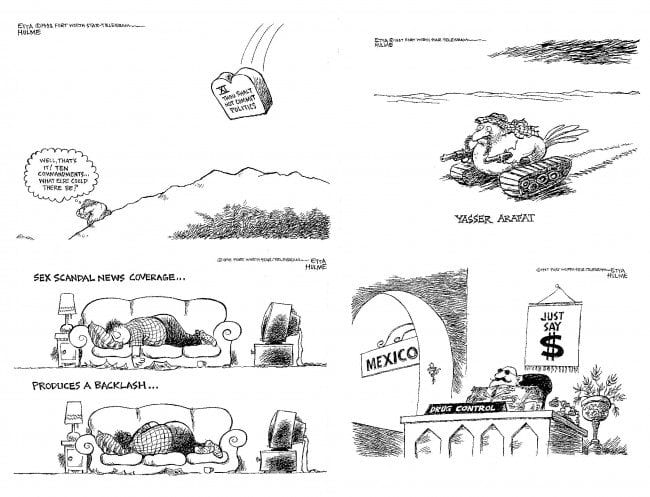

For 36 years, she drew editorial cartoons for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, where she was a decisively liberal voice on a conservative newspaper. Her last cartoon was published in December 2008, one farewell poke at two of her favorite targets—President George W. Bush and his cohort, Dick Cheney, the president of vice—as they left office.

The National Cartoonists Society twice named her best editorial cartoonist of the year—for 1982 and for 1998 (this last, mind you, when she was 75, long past everyone else’s retirement age; but then, Etta never really retired). She served as president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists in 1986-87.

Etta never won a Pulitzer, but she should have. And she was admired by all her colleagues in a famously opinionated profession—including those who’ve won Pulitzers. Philadelphia Daily News/Inquirer’s Signe Wilkinson, for one: “She was the dean of our little band of women editorial cartoonists,” Wilkinson told Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs, “—though, in her self-effacing way, she would never have claimed that spot.

“She never won the Pulitzer, though her work is as [strong] as most who have, but her cartoons won higher honors,” Wilkinson continued. “For example, on [Interstate] 95 coming home from a women’s march in Washington, I remember looking over at the car in the next lane and seeing a Hulme cartoon about equal rights blown up and plastered in the window. That’s the mark of a successful cartoonist. Her work lives on.”

And Mike Luckovich (Atlanta Journal Constitution): “She was a great cartoonist and person. She was fearless in standing up for the oppressed and less fortunate, while never taking herself too seriously.”

And Ann Telnaes (WashingtonPost.com), whose comment was shorter but just as true: “A lovely woman and a kickass cartoonist.”

And Jen Sorensen (Austin Chronicle et al.): “As a cartoonist, she had a wonderful line — a very accessible, funny drawing style that I am amazed she pulled off into her 80s. Politically, she was right up there [with] Molly Ivins and Ann Richards in the great tradition of witty and wise Texas women. I think she deserves far more national recognition for her place in history.”

And Jim Borgman (longtime Cincinnati Enquirer political cartoonist): “Only in retrospect do I appreciate Etta’s remarkable place in the storyline of editorial cartooning. A lone female voice, liberal at that, in 1970s Texas — that’s one lonely perch in an already solitary profession. Etta was confident, brave, funny and warm, with an engaging drawing style that focused on people more than symbols. She was under-appreciated by those of us who should have known better.”

Kevin “KAL” Kallaugher of the Baltimore Sun, The Economist: “Etta Hulme was a delightful study in contrast. On the surface an endearing genteel and humble grandmother, beneath a punishing pundit with cunning wit. I loved both those Ettas and will miss both of her.”

Ed Stein of the now-defunct Rocky Mountain News, who followed Etta into the presidency of AAEC, wrote: “Her cartoons were a lot like her. Rendered in a soft, feathery line, her disarmingly quiet, smartly captioned drawings packed a surprisingly biting punch. An uncompromising liberal’s liberal on a conservative paper in a conservative town in a conservative state, she had to be—and was—one tough, feisty lady. She’s been described as the den mother to all the guys (and the few lonely gals) at our annual conventions of editorial cartoonists, That description doesn’t come close to doing her justice. She was the equal of the best of us as both an artist and commentator, and more than capable of holding her own in our mostly testosterone-driven profession. And we loved her.”

She may have been the AAEC den mother, but, as Ben Sargent (another Pulitzer-winner) at the Austin American-Statesman said, “She never made a big deal about being a female cartoonist. She was just a cartoonist.”

Her drawing style was as unique as her visual commentary was sharply pointed: folksy, down-home, but still somehow startlingly modern.

“I draw mostly to entertain myself,” she said once, “—as I’ve always done since I was a kid. So it’s not like a real job that you train yourself for and then eventually retire from.”

At the Star-Telegram, one of her former colleagues remembered his favorite “ettatorial” cartoons when he heard of her death.

Bill Youngblood, a retired editorial writer, recalled a cartoon drawn after Charlton Heston was elected president of the National Rifle Association. Etta depicted Heston as Baby Moses being plucked from the Nile while a voice said, “Watch out, he has a gun.”

Reporter Tim Madigan, writing the paper’s obit for Etta, asked former Star-Telegram publisher Wes Turner whether her cartoons ever gave him headaches. Said he: “Hell, yes.” But, he went on, the grief was worth it. “Her political persuasion and mine diverged, but I thought she made our paper better because she certainly got people talking and got people thinking, and that’s what a good political cartoonist does.”

In a 1993 interview, Etta said: “Most of my hate mail — sure, I get hate mail — calls me a liberal. But whatever opinions I have come naturally without my trying to take any particular stand. If I go on too long without one of my cartoons gettin’ me in the soup, I start to worry. A cartoonist ought to provoke.”

Outspoken, that was Etta.

Or as she said of her readers: “They just have to live with me. I’m an opinion person.”

Perhaps the best way to get to know this woman whom we all loved is to listen to her—as I did when conducting an interview with her in her office at the Star-Telegram in October 1998— and to read what she wrote about herself in a 1980 autobiographical article. We begin with the latter, into which I interspersed bits and pieces from my interview with her. When I talk, it’s in bold italic; the rest of this is Etta in her own inimitable Texas drawl, herewith—:

I've been called an iconoclast and a harmless housewife. I like to keep my options open so I’m willing to agree to both descriptions.

I was born [December 22, 1923] and raised in Somerville, Texas, where my family had a grocery store. Working in the store after school and in the summers, I think, gave me a pretty good notion of the human condition. I learned that the customer always thinks he is right and how to cut a pound of cheese (within an ounce). And I had access to the wrapping paper to draw on. I also did a lot of soap carving.

I majored in fine art at the University of Texas, so when I graduated, I went out to California and the Disney Studios, assuming I could get a job. (Chuckles) It was World War II, 1944. And, of course, the men were being drafted so Disney was full out hiring more women. They had some in animation, but most of them were shuffled off to Ink and Paint.

I went in for an interview, and they told me to come back with some more samples. So I drew some more samples. And I was put in the training program. Twenty-seven fifty a week was the pay. It was great. Marvelous training. Hard on my myopia but good for facial expression and body english. Most everybody progressed up through Clean-up and Breakdown and eventually got to be a regular in-betweener. I was pretty far down on the row, but I was a breaker-downer and a cleaner-upper and an in-betweener. Got to work with Ward Kimball. Drawing for animation gave me a compulsion to close all the lines neatly together [so they could contain color without it spilling into a neighboring shape], and I’m still struggling with this.

I was there only for about two years. And then I departed and came back to Texas, and worked in commercial art in Dallas. And I went on from there. I was an art bum. I went up to the University of Wisconsin one summer and took General Writing. I just bummed around for a while (laughs) and came back and worked in commercial art in Dallas again, and taught school in San Antonio and formed a little art school, a Little House School of Art in a little pink stucco building.

All the WWII veterans were on the G.I. Bill. They could go anywhere. Well, (laughs) some of them came to the Little House School of Art and ended up being sign painters. (Chuckles) But they had some good teachers there besides—I mean excluding—me. (Laughs) I spent a long time there.

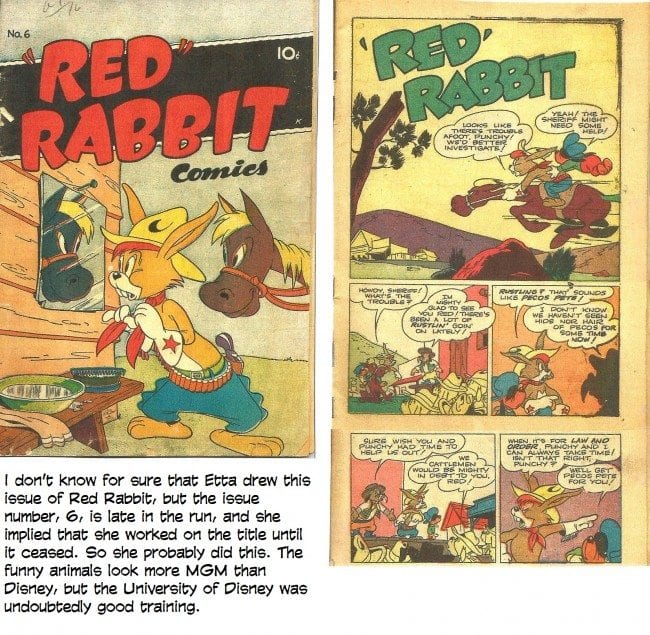

Then I went up to Chicago and decided that I needed a job. And so I walked in to Dearfield Publishing Company on West Washington Street with my portfolio and got to jabbering with a fellow named J. Charles Laue who published a few comic books. He was not a large operator, but he was a wonderful friend to me. He gave me a spin-off he’d gotten from Hanna-Barbera. It was Red Rabbit. It was a comic book parody of Red Ryder.

Red Rabbit’s horse was named Glueball and his sidekick was named Punchy. You know, Red Ryder had an Indian sidekick and he always did good things. Red Rabbit was a white hat rabbit.

I got that and went to the Art Institute at night, a course in lithography. Then I brought Red Rabbit back to Texas. It paid next to nothing, but (chuckles) I could live on next to nothing. I did it on my Momma’s back porch in Sommerville. I could draw it anywhere and mail it in. And this was about the end of the comic book heyday, so Red Rabbit didn’t last very long (laughs), about six months. I don’t think it was even a whole year.

I became a displaced cartoonist in 1952 when I went to Germany and married Vernon Hulme. Before that, we went around together for a few years—we met in college—and we were going to get married. Then there was the Korean unpleasantness, and he was dispatched to Germany instead of Korea. And I decided, “What am I doing sitting here when I could be in Europe?” (Laughs) So I went over there and we got married and lived over there for a couple years, and I blew off cartooning for a while. I think I made a poster, or an invitation, or something like that (laughs) for an Italian party, but that was about the extent of it. And then we came back to the states—to Austin where he had to complete one more year to get his chemical engineering degree.

In Austin, I produced Kay (the first of four children) and an editorial cartoon a week for the Texas Observer. A friend told me they used cartoons. They were operating on a shoestring, as they always did, and I think it was five dollars for a cartoon, and they used an occasional editorial cartoon. Well, these were the great days of Civil Rights. And so I did a few cartoons for them, my first editorial cartoons.

We moved a lot in the following years. In Houston, I produced Helen and a few commercial cartoons. In Corpus Christi, I produced Charlie and a few commercial cartoons. In Shreveport, I produced John and gave up cartoons to catch up on the laundry.

After Shreveport, we shuttled to Odessa, Texas to Arlington, Texas, to Detroit and back to Arlington. By then there were no moving companies left that we were on speaking terms with so we’ve been here [in Arlington] ever since.

After serving time as a Girl Scout leader, Den Mother in Cub Scouts, and Potato Lady for the Rotary Club lunch (good recipe but it serves 400), I got back to cartooning. I showed the kids how to use the steam iron and where the peanut butter was, got out the phone book, and looked up the advertising agencies and so forth. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram was on my hit list. They were using syndicated editorial cartoons in the afternoon paper. Harold Maples was doing editorial cartoons for the morning edition. I made a nuisance of myself until they agreed to print a few on a freelance basis. In 1972, this evolved into a regular job and the five a week I do now.

When I came in with my little portfolio, it was with theatrical cartoons. And I took them and showed them to the Entertainment Editor. He said, “We don’t use graphics.” (Laughs) And they hardly ever did, you know. But then, he brought me back to see another editor, and this other editor brought me back to see a Mr. Al Redus. He had been there forever, in my judgement. He was a very portly gentleman, and a very conservative gentleman, and he had some of my editorial cartoons from the Observer, and I said they were probably too liberal for you. But he was courteous to me. (Laughs)

Redus let me do cartoons for a while, freelance. In trying to persuade Jack Butler, the main editor, to put me on the payroll permanently, I did a little cartoon of me, playing a violin (laughs), begging him. (Laughs) And that amused him into letting me be on the payroll, but not for any extraordinary amount of money. (Laughs) We always said we’d draw for next to nothing, and they let us.

I was doing three a week at first, and when it did work into the job, it was five a week. And Harold and I were both here. He was still on the morning. I was doing the afternoon.

Etta worked at home in the early years—in a “gazebo” in her back yard. She would telephone her editor when she had an idea. And he’d approve it over the phone.

It was usually acceptable. I don’t give a big, big hit in the middle of the stomach or anything. I sneak around back. (Laughs) Ben Sargent was kind enough to give me the best description I ever heard about my cartoons. He said, “She doesn’t chop them up with a hatchet. She smothers them with a pillow.” (Laughs)

After getting approval, Etta drew the cartoon and brought it in to the office herself. That routine changed with Harold Maples’ death in 1982. The Star-Telegram hired another cartoonist, Mike Shelton, for the morning slot, and, as Etta explained it—:

They said, “Well, he’s going to be here in the office, so she might as well be. ” And I said, “Well, you going to move me down here?” “Well, yes, we are.” And I said, “Well, I want the room with the windows. I’ve been on staff long enough.”

Mike was a wild man. He’s an extremely conservative—he thought himself Libertarian. He used to come and march in here in the morning, a dear person, but he was misguided and he thought I was misguided too. (Laughs) So he’d come in and try to save me. That never worked, (laughs) but we had a great relationship.

How, I asked, did the paper tolerate two diametrically-opposed editorial cartoonists?

“Well,” Etta said, “that’s the perfect world. (Laughs) This is a great paper to work for. I hate to think that I was totally, predictably Liberal, or Conservative, or labeled; although probably most people that complained about me complained because I’m a wild-eyed Liberal. Yes, I have had complaints. (Laughs) Complaints are what we live for, of course, but we shouldn’t. We should just convince them and they should say, ‘Oh, I was wrong. Your cartoon convinced me.’ (Laughs) And editors should say, ‘What a lovely cartoon. Let’s write an editorial about that.’” (Laughs)

“The best complaint I’ve ever had,” she went on, “—and I really loved it, and I have no idea what I’ve done with it now—was from an anti-gun control person who put [my pro-gun control] cartoon up on a wall and shot bullets through it and then sent it to me.” (Laughs)

About an hour or so into the interview, another staffer, a woman, knocked on the door of Etta’s office, opened it and stuck her head in, saying, “I was just wondering about you. I’ve never seen this door closed.”

By way of explaining the closed door, Etta introduced me: “This is Bob Harvey. He’s from Cartoonist Profiles magazine. He’s trying to sell me a vacuum cleaner.”

The woman bid me hello and left, and Etta and I then talked about her daily routine a little and about making cartoons.

I really like to kind of have something in mind by one or two o’clock, so that gives me enough time. And it varies a great deal. Sometimes, it’s your first different idea that lights up: it’s okay. Sometimes, it just never happens (chuckles), and three o’clock comes and you don’t have nothing. I start scratching through a big pile of paper up there [on top of her filing cabinet] and see if there’s a germ of something that I can go back and revive. (Laughs)

There are all kinds of desperate lunges off the cliff every day to try to say something, you know, that you read into something that just kind of gets to you later.

I asked: Okay, so when you make a rough sketch, do you show the sketch to anybody before you turn it into a cartoon?

Yeah, if I can find him. I show it to Mike Blackman. But if I can’t find him, I show it to somebody else if I think they’ll like it. And if they don’t, I’ll just draw it anyway. (Laughs)

I said: So you don’t have too much trouble getting your cartoons approved.

No, very, very little, very little.

And that, she confirmed, has been the case from almost the very beginning. I asked her if she thought an editorial cartoonist was a crusader or a jester or a reporter.

None. None of the above. A crusader? Well, in a sense, I mean, in that you state your opinion. But if you’re too overbearing in it, I think it’s counter-productive. And that’s where humor comes in. Humor is useful, but it’s not the be-all and end-all, and it really hurts our feelings, many of us [if our cartoons are thought of as just humor pieces]. (Laughs) People say that what your editor decides is funny is the primary criteria. Well, it’s one. But if funny can deliver a message, then this is where you step in it up to your knees because you look at your cartoons and there’s some that really don’t have that much of a message. (Laughs) You know, I go through a drawer-full, maybe one in ten. But I’m trying. (Laughs) Ideally, a cartoon should have a position.

And there are things that I kind of crusade about. There are subjects that I feel strongly about and will probably never change my mind. And those are the ones that get reactions that I never can control. I don’t agree with my cohort next door who is a welcome and delightful person, and an excellent writer—and an advocate of the Second Amendment right to carry. And she’s a responsible individual, and that’s fine. (Chuckles) But I don’t trust everybody to carry a gun, I’m sorry. (Laughs)

But anyway, that’s one of my “causes.” Of course, Women’s Rights, back there when it was still an issue (laughs), which it no longer seems to be. [Not that gender issues have all been resolved:] only if you think that sixty-nine cents to seventy-two cents is that much of an improvement in the average salary. (Laughs)

Cartoons that merely report on some current event without expressing a definite point of view did not earn Etta’s whole-hearted approval.

I don’t think they’re editorial cartoons, not what an ideal editorial cartoon should be. But there are many of them out there, and I’m responsible for some of them, so I can’t fuss about it. But just because something has happened that may be a major news story, I don’t have to comment on it. If it’s something—nobody wants the Federal Building to blow up. Am I for it or against it? (Laughs) What can I do? Terrorism is bad. Okay, Terrorism is bad. Who’s going to disagree with that?

A satisfying cartoon is a cartoon that makes you get a little bit of a buzz, and you think you’re making a point, you think that you’re making noise with the person reading it. The woman who’s the editor at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said it: I think it’s kind of an expression of journalism—“a sharp stick in the eye.” (Laughs) She said a cartoon should be a sharp stick in the eye, and I thought that I liked that a little bit. I think that other people have used it, have latched on to it.

I think the weakness of an editor is not setting out to rile people up. If a cartoon is viewed as something to lighten the page, there’s no purpose in putting them in there to start with. Certainly Thomas Nast wanted to lighten the page. (Laughs sarcastically)

But we have to have people who are not fair-minded. If we don’t have them, well, who’s there to win over? (Laughs) We’ve got to depend on it, their stereotype. (Laughs) “You wrong-headed idiot, I need you.” (Laughs)

I chimed in: “You need the misguided millions.”

Etta elaborated: “The satirically-impaired. And they’re out there, they really are.”

I asked if she felt when she was starting out that she had been put in a special category as a woman cartoonist.

“No,” she said, “I don’t think so. I just was a cartoonist and always have been. Ain’t any special feeling about it now, as far as I’m concerned.”

Were you paid less than a man cartoonist? She admitted she was paid less than her predecessor at the Star-Telegram but he’d been there longer. She laughed and said: “I think I’ve probably caught up by now.”

Did she ever feel, as a woman and as a political cartoonist, that she’d been discriminated against in some way?

“No,” she said. “In my case, there’s never been any discrimination that I can detect.”

Did she think that was unusual?

“No,” she said, “I don’t think so. I don’t know, do other women cartoonists think it’s unusual? I’ll have to call them and ask them.”

A couple years before, Etta had been on a panel of three women cartoonists at an AAEC convention, Signe Wilkinson and Ann Telnaes being the other two. Signe started the assessment of the poor represention of women in the profession by memorably speculating that their panel might have been entitled “Bitch, Bitch, Bitch”—or, perhaps, “Ho, Ho, Ho.” Three being the operative number.

Later in the ensuing discussion, the panelists considered how the culture at large teaches stereotypes that women have to deal with all their lives. It all begins with child rearing. Etta wasn’t quite sure about that:

“I raised my son to be a boy,” she said, “and my daughter to be a girl. And they seem to have turned out all right.” Then she chuckled.

I don’t think any of this means that Etta didn’t care about feminist issues. I’m sure she did. But I also suspect that she didn’t attach as much significance to sexism as she did to doing the best cartoons she could. Only one or two of the cartoons in her book, Ettatorials: The Best of Etta Hulme, deal with sexism. The others target her favorite foes—environmental protection, health care, welfare, gun control, the havoc of war, and gender relations.

In 1980, she wrote this: “On being a woman in editorial cartooning—. There aren’t very many women editorial cartoonists for the same reason that there aren’t very many women bricklayers or surgeons. There have been times when being a woman has been an advantage; times when being a woman has been a disadvantage.

“My advice to aspiring cartoonists is the same to males and females: Learn all you can about drawing. Read everything you can get your hands on, especially news and opinions. You must be persistent and it helps if you’re lucky because the quality of drawing and humor has been high for young people entering editorial cartooning in the last few years. Also, bake an occasional batch of cookies for your photoengraver—his good will is essential.”

Is baking cookies one of those advantages of being a woman? I dunno.

By the time I knew Etta, she was grandmotherly in appearance but usually satirical in demeanor; she had a wicked sense of humor and an appropriately perverse perspective.

During my interview with her, she made a casual comment that seems to me, now, to explain a lot—perhaps the best insight into Etta’s attitudes, about feminism and virtually everything else.

“I come in to the office about nine-thirty,” she said, “and I have my editorial board meeting, which, sometimes I attend and sometimes I don’t. I go if I hear them laughing loud. (Laughs) Particularly if I hear them shouting. Shouting is best. I’d consider those were some pretty entertaining editorial board meetings. They meet in a small room,” she continued with a grin, “and I end up sitting in the hall, making cracks.”

Making cracks. Poking holes. Deflating pomposity and revealing hypocrisy. Etta Hulme was an expert at all of that. And here’s a gallery of her ettatoons to prove it.