THOMPSON: Ah — this is where your clash with mainstream comics over creators' rights came to a head, right?

ARAGONES: The whole thing started when I brought some pages to DC, as I usually did, and when I arrived there, Joe said, "You have to go and see..." Uh... [Aragones searches for the name, can't think of it, and holds his hand about four feet from the ground.]

THOMPSON: [guessing] Paul Levitz?

ARAGONES: Paul Levitz. [Thompson chuckles.] And so I went to Paul Levitz and he said, "You have to sign this." And it was a work-for-hire contract. I already knew about the work-for-hire contract, which I never intended to sign, and I said, "But I have never signed these and I don't want to sign it. I have always worked without having to sign anything." And he took the check and ripped it up right in front of my face. My God, nobody has ever done something like that to me. I said, "This is it. No way am I ever going to do anything that I don't own. Never." So for many years I never went back to that company. But that doesn't mean I wasn't still good friends with a lot of the people there. Joe Orlando is a dear friend of mine, and Julie Schwartz, so I'd always go there and say hello to all my friends at DC, whom I adore. And I have so many stories of things that have happened at DC, friends that I met. One of the presidents, Mark Iglesias, was a friend of mine. I met him a long time ago when Warner merged with Kinney. He was the president of the comic book division, and also the owner of the marina where I had my boat. So we became friends. It was a very beautiful era and I still love all the people at DC. Professionally, it's different. The way I was treated...

I would go there and they would say, "There's no way that we can ever give any rights to anybody." They would take books out to prove to me that it was impossible.

THOMPSON: Right, they'd be breaking the law if they let you keep the copyrights.

ARAGONES: And every time I talked to that tall fellow at Marvel, he also said it was impossible. And I didn't have any contacts in Marvel, so there was no way they were going to do it. They later changed their mind, but at that time, there was no way. I never talked to anybody about Groo, because I didn't want anyone stealing the idea; so I was selling "a comic book" which I had in mind. And they weren't even able to talk on a theoretical basis — nothing! They wanted nothing to do with it. So I decided I was going to publish myself. By now Pacific Comics had published the first few issues of the Kirby book [Captain Victory], so I thought, "Well, they have very good distribution. These are the people I need." So I had a meeting with the Schanes brothers at Canter's [a famous Los Angeles all-night deli, much plugged in Groo], and I showed them my project. I had already talked with Mark [Evanier]; he was going to help me.

By that time, Groo had appeared in Destroyer Duck. Mark had called me and asked, "Do you have a piece for this benefit thing?" I said, "Yeah, I have this character that I've been toying with."

THOMPSON: It seemed really appropriate, since Destroyer Duck was supposed to finance Steve Gerber 's lawsuit against Marvel over the copyright to Howard the Duck.

ARAGONES: Yes, very. So he sent it to Eclipse and it appeared in Destroyer Duck #1. By now I had drawn a lot of single page drawings of the character, a few pages of which were later incorporated in the special that Eclipse did. So I talked to the Schanes brothers and they said, "Not only will we distribute it, but we'll publish it for you," which was terrific. It saved me the trouble of having to spend time doing things other than drawing. And it came out and that was it. They weren't too happy with it, because it was humor. Every second issue they wanted to cancel it again, and I would tell them, "O.K., I'll buy it, I'll publish it. I'll be the publisher. Let's make an arrangement. It'll be my company." And immediately the publishers would say, "Well, we'll do another issue." [Laughter] But they never had too much faith in the humor comic.

THOMPSON: What kind of sales were they racking up on Groo at the time?

THOMPSON: What kind of sales were they racking up on Groo at the time?

ARAGONES: I have never been able to get out of anybody how many they printed, but in the beginning, at issue number one, it was about probably 50,000 copies. Later issues were lower, to the point that they were only printing 30,000 or less of the early Groos. Sales were average — not too good because, again, it was humor. The only thing that probably saved me was that I had been working with MAD for so many years that I had a certain following that liked humor — or liked what I do.

THOMPSON: And presumably you also got at least some Conan fans, because sword and sorcery was going very strong at that time.

ARAGONES: Yeah. It was not an offensive comic. It was drawn professionally and with care. Then Pacific ended up going out of business because of many other things. I don't think they were that interested in the publishing end of it. They were more into distributing and big business. By now Mark had talked with the people at Marvel, or the people at Marvel had talked with him, about doing it for a new line they were going to do called Epic. That was fine as far as I was concerned. So we started negotiating contracts, I told the people at Pacific, and everything was all right — they were going out of business and I said, "Well, I'll continue with you until we start with Marvel," and they said fine. It just happened that they were planning to do a special issue, and by then they'd gone out of business. I couldn't give it to Marvel because we were still negotiating, so it went to Eclipse. And by the time that special came out, the contract was finished. It took a long time. It took months and months to negotiate.

THOMPSON: Doesn't it always with Marvel, though?

ARAGONES: Yes. [Laughter] This one even moreso because it was the first comic ever owned by somebody else to get newsstand distribution. It was very strange. And we had a lot of legal details to be solved over there; things about the indicia, the names on the splash page, stuff like that. But when everything was satisfactory for everybody then number one came out. So there wasn't even a lag between the Pacific issues, the Eclipse issue, and the Marvel issue.

Groo: The Technique of Humor

ARAGONES: The big problem was that when I did the Marvel number one I didn't know what to do. It had to be a number one because it was totally different from the previous version. Out of respect for the readers I already had I didn't want to start all over again, but I also didn't want all the new readers I was going to gain wondering what I was talking about. How was I going to start off? That was what really took me a long time, and I figured out the best way: that's how the Minstrel started. I figured out that in issue number one I'd have somebody telling stories about Groo. It was good for the new readers: they could understand it because I had someone talking about Groo, how idiotic he was. And it was good for the older readers because he was part of a nice continuity without having to start all over again. And then by issue two I was back on track. So that's what I did and it worked all right: the transition was smooth. Of course, first issues always sell very well, and now we were printing hundreds of thousands because now it was in the direct sales and the newsstand sales. The sales have been very steady.

THOMPSON: Does it sell better in the direct sales market or in the general market?

ARAGONES: It sells about the same — a little more in the direct sales market. Not a lot. Still, it's a humor book, and the direct sales market is such a false market that we really don't know how many people buy it to put it in a plastic bag, how many read it, and how many buy two copies. So it's very strange. I don't know what's going to happen with it.

THOMPSON: It's a hard market to read. Let's talk about how you assembled the "Groo Crew" — Mark, Tom, and Stan.

ARAGONES: Well, before I worked with him. Mark has always been a dear friend of mine and I've known him for many years. And he has become invaluable. What was done for Bat Lash by…

THOMPSON: Denny O'Neil?

ARAGONES: Denny O'Neil, thank you very much. What Denny O'Neil did for Bat Lash was give him a voice, a Western voice, and that's what Mark has done for Groo. And more — he's given it his special brand of humor. Stan Sakai also had been a friend and a very good letterer, as well as a very good artist. And Tom Luth is an excellent colorist. So it was a very natural meeting; they have stayed and they have enjoyed the relationship. Without Mark, Groo would talk a little bit differently, because the characters write themselves. No matter what people want to do for a character, the character takes a certain direction. You're not writing him — you end up writing for him. Groo started off less stupid, but once you inject oral humor, which is what Mark does very well, it plays more on the stupidity of the character, so he becomes a little more stupid. So Groo has become stupider than he was when we just started it, but it hasn't been any trouble. It's easy.

THOMPSON: How far ahead do you think your stories up? I remember reading an interview where you talked about how many ideas you had, and one of them being that Groo would acquire a dog. This was in '82, and the character turned up four years later...

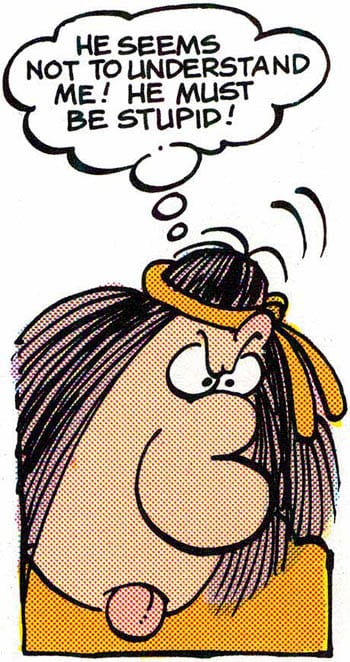

ARAGONES: Yes, I'm a few issues ahead. Like right now I'm inking #56, I finished #55. Issue #51 is out, I'm writing #58 — I have to give it to Mark pretty soon. See, I can play with a story, because I have many months to work on it. Other artists have a month to ink, a month to pencil, and everything. I have a month to do everything, but since I'm working on three or four issues at the same time — inking one, penciling one, writing one — I have three months to write it. So I take a long time to write a story. A humor strip is not like a regular adventure strip. It's harder to give variety to the character. With a hero strip or an adventure strip, being so close to life, you can do a lot of things, you can play in a lot of fields. But when you are dealing with humor, you have certain parameters you can't get away from. If you look at a comic strip, it's always the same. It's one gag. The whole 50 years of Blondie is one gag. It's how you say it, and how comfortable you are with it. American audiences are not familiar with humor in comics so they want a humor comic to be like a super-hero comic, and they want a lot of things that cannot be done. I can't take Groo out of what I think is humor. I can't have him fighting Conan, no matter how many fans want it. Groo belongs to a world of humor, and Groo is going to be a barbarian who's stupid, and through his stupidity, he's going to ruin either a town or a friend; something's going to happen. A lot of the readers don't understand that. They want it to be changed. But if you look at Asterix — many Americans are not familiar with it. But Asterix is a very comfortable character because whatever he does, it always ends the same. They sit at a banquet, they've tied up the character who sings too much, and for the last 30 years, that's how that story's been ending. Well, mine change a lot because at least I have a little more to play with. [Laughter]

ARAGONES: Yes, I'm a few issues ahead. Like right now I'm inking #56, I finished #55. Issue #51 is out, I'm writing #58 — I have to give it to Mark pretty soon. See, I can play with a story, because I have many months to work on it. Other artists have a month to ink, a month to pencil, and everything. I have a month to do everything, but since I'm working on three or four issues at the same time — inking one, penciling one, writing one — I have three months to write it. So I take a long time to write a story. A humor strip is not like a regular adventure strip. It's harder to give variety to the character. With a hero strip or an adventure strip, being so close to life, you can do a lot of things, you can play in a lot of fields. But when you are dealing with humor, you have certain parameters you can't get away from. If you look at a comic strip, it's always the same. It's one gag. The whole 50 years of Blondie is one gag. It's how you say it, and how comfortable you are with it. American audiences are not familiar with humor in comics so they want a humor comic to be like a super-hero comic, and they want a lot of things that cannot be done. I can't take Groo out of what I think is humor. I can't have him fighting Conan, no matter how many fans want it. Groo belongs to a world of humor, and Groo is going to be a barbarian who's stupid, and through his stupidity, he's going to ruin either a town or a friend; something's going to happen. A lot of the readers don't understand that. They want it to be changed. But if you look at Asterix — many Americans are not familiar with it. But Asterix is a very comfortable character because whatever he does, it always ends the same. They sit at a banquet, they've tied up the character who sings too much, and for the last 30 years, that's how that story's been ending. Well, mine change a lot because at least I have a little more to play with. [Laughter]

So I have to bring in a lot of new characters to compensate for the very rigid limits I set for humor. I have to think of a funny ending: I just can't have the hero beating the bad guy, like a regular comic book. I can write "serious" comics: it's very simple. I can give you 20 "serious" stories for each Groo story, because the only thing you have to change is the villain. Somebody attacks something, the hero comes and saves it, and that's it. No more; no less. You can have more pages of fight, you can have a lot of more dialogue if you want, but it is exactly the same. With humor, no. You have to have a gag. You have to have jokes. And you have to spend a lot of time making it a little different even though it is the same. It's very complex, but I am very grateful that I have 30 years of humor writing behind me.

When you bring in a character, there has to be a need for that character. I needed a very intelligent person, which is how the Sage came to be. When we were at Pacific, every comic that you did, you always left a five-pager at the end for a new artist to introduce an upcoming character. So I'd left five pages open in issue #1 to introduce some other character, but of course the five-page story didn't show up. I'd decided that deadlines were very important to me and I wasn't going to miss one, so I created a character over a couple of days so that our issue could get into print. I thought of a catapult joke, but suddenly I realized that Groo couldn't cope with the concept of a catapult. So I had to create a new character for the joke — it was a very good joke and it would work very nicely — so I created the Sage. Just like that. Not too much thought behind it, but I wanted a guy who was very wise, a little mixture of Mr. Natural and the guy from Smokey Stover — that guy with the beard. It came out and it worked all right. Now I had a character who was a wise character. So any time Groo needed wise thought, I had the Sage. Any time he needed a bandit — I created Taranto, who was a bandit. Every time I need a character I will create him.

The Minstrel's terrific because I can introduce other stories that have nothing to do with that continuity, even though Groo is not a continuity. One of my early memories when I was a kid was reading The Spirit. The Spirit is one of my favorite comics ever. And what I learned from Eisner was that he could tell in seven pages a story that you could read anytime without ever reading any of the other stories and it was there. It had a sense of humor, pathos — it was perfect. 1 liked that, that I could go to back issues and read it comfortably. And also the stories written by the Donald Duck...

THOMPSON: Carl Barks?

ARAGONES: Carl Barks. Carl Barks would tell a story, and no matter what issue you read, it was there — complete, perfect, great ending, great adventure, and it was ended. So I figured out that was what I wanted to do. Oh, it would be very easy to make a continuous saga out of Groo. But then you couldn't read a back issue and enjoy it just by itself. And I wanted the kids, or the people who read Groo, to have the same feeling that I got from the comics. To be able to read an old issue and enjoy it and put it aside.

See, I don't want people to collect Groo. I want them to read it and forget about it. I'm glad they're keeping it, because they can look back at it again and again. So each character has a reason to be, but they are not a continuity. They can be interchanged. Groo has no age. Groo has no history: Characters are born old. You do all their lives because people want to know more about them. But I know less about Groo's parents than any reader. They can imagine his parents as well as I can.

So I've been creating characters for him as the need arises. With Groo being a loner, I had arrived to the point where I could write a lot of loner stories; but he needed a companion. I figured a companion would do him good, and would provide a change of pace. Humor is fine, but that change of pace is very important. So a companion was important.

Now what? If I do another human, he's going to take over the comic within three issues because Groo would become a second banana.

THOMPSON: If he's smarter than Groo then he'll fake over the comic. If he's stupider than Groo — well, that's sort of hard to imagine.

ARAGONES: Absolutely! [Laughter] No way any character could! So I thought of an animal. And the first thought behind Rufferto was that the only companion Groo would have would be an animal he wanted to eat. Why else would Groo have an animal? But everybody loved Rufferto when he came out, so then I said, "Oh, let's play with him a little more, and a little more." And he stayed. He's an animal, but he has a certain devotion toward Groo. The only people who could love a mercenary like Groo would be an animal. A dog. A dog will love his owner no matter what. He doesn't know if he's a criminal or a good guy. A dog loves his master. The relationship can work, and it has, Rufferto's still there and they work together.

Collaboration

THOMPSON: How do you and Mark work together? From what I've heard, it's a fascinating process.

ARAGONES: Once I have idea, I go to Mark and we sit down and I say, "This is what I'm going to do." He laughs or says, "Well, yeah," or "it's too close to that." Then I write the story out on 8 1/2-by-11 sheets of paper, sitting at the coffeehouse, and when I have 22 pages, I sketch it out in very rough pencil. Then I draw it in blue line on the big paper, and go to Mark and read it to him right there. And if he understands what I have there [laughter] then he goes and writes the dialogue correctly, puts gags in it, writes the poetry; often he changes the order of the story, sometimes he makes a change in the ending. He has saved many stories because he finds things — not that there's a deficiency in the storytelling, but he improves it. He finds something better. Much better. And of course he has carte blanche to do that. Sometimes I don't agree with what he says and we talk about it and change back stuff. But that's very rare because he's a very good writer. And if his change makes more sense, I'm not a fool. Anything that improves it I take! So he does a lot of...

THOMPSON: Editing, basically.

ARAGONES: Oh, yes, very good editing. And a lot of very good writing. All the poems. Sometimes I see where a joke — a written joke — could go. So I write, "Joke here," or, "Mark, please save this panel" [laughter] or "Put Mark-ism here," and he does that, too. Then he gives the pages to Stan Sakai. Stan Sakai does the lettering, following Mark's new dialogue. Stan can follow the drawing because it's in blueline. Then it comes back to me. Then I start doing a little more penciling because now I have to change the expressions. See, sometimes 1 didn't know what the final dialogue was going to be. So now I start putting in expressions that fit the dialogue. But nothing very much gets changed. Let me show you. [Showing a page of rough pencils] This is the blue pencil that I'm talking about. As you can see, none of the drawings gets changed. Then I put in all the lines — the panel borders and balloon outlines, and then I start...

THOMPSON: So you draw all the panel and balloon borders?

ARAGONES: Yeah. I like the balloons to fit the style of the comic. I put a little more black in.

THOMPSON: Your penciling is very loose...

ARAGONES: Very loose; very loose. When it comes back to me, I just finish it up a little more completely.

THOMPSON: Have you ever tried working with tighter pencils?

ARAGONES: No, it's not necessary. Because I know what's going to be there. I only pencil it out entirely when I'm doing, say, a Japanese uniform, for the first time. I get all my research material for Japanese uniforms and I go through it until I really understand. I build a few samurai suits in plastic and then I understand it perfectly well so it's as natural to me as a regular shoe. So I know how everything gets tied up, all the knots. The first time it's hard, but no more; then I can do it with very little pencils because I know exactly how the whole thing goes.

THOMPSON: You actually do a lot of research for Groo

ARAGONES: Oh, yes. Very much.

THOMPSON: It sounds surprising, but when you look closely at the book you realize how authentic a lot of the backgrounds are. I noticed you have the cartoonist's traditional collection of National Geographics.

ARAGONES: Oh, yes. The research gives you a feeling for the place you're going to. One of the stories that I was doing — I don't remember what one it was — took place in a village set on stilts. I was drawing it and had already done a couple of pages, but I realized it would be more proper if it was a New Guinea type of environment — Papua. So I went back to my National Geographies and started looking through them. And then you get an idea of the houses, the decorations, the costumes. And after you look, you make a few sketches just to familiarize your hand with it. And then you just close the magazine, forget about it, and invent your own, based on the suggestion your mind has now of that particular place. I did the same thing when I did a few early stories set in Africa. You go through all the books — statues, decorations, weaponry — and from there on you... Japanese, the same thing. Castles. You don't exactly do the research for the comic. You do it for you. Once you know a lot about a subject, everything comes very comfortably and it's not out of place. Even if it doesn't show up in the comic, it has a feeling for what is important. With a little research, anybody could probably just copy something and make it just as good, but I feel better. So I do a lot of research about everything that has to do with a particular period.

THOMPSON: Your technique has the double quality that your work is well researched enough to be logical and feel right, but it also has the spontaneity you like.

ARAGONES: Yeah. The looser humor is... You see, when I'm doing cartoons for MAD. I want to be looser. Sometimes I can't because MAD has very strict guidelines about drawing. But a cartoon has almost no background. It has to look very simple, like the Marginals. The idea's there, you don't have costumes, the guy's just dressed — if he's a fireman he has a little fireman hat. But the less you put, the easier it is to understand. But now I'm drawing a comic book. Everything I have been talking about for cartooning I have to totally disregard. Now I need environment. I need ambiance, I need costumes, I need continuity, I need directions for the characters to come in. And suddenly everything is different. It's two totally different jobs. The humor is in the content. The humor is in the characters themselves. But the backgrounds can be as elaborate as you want. And the more you put in, in my opinion, the better established the character gets. You establish where everything is: if he is in the desert, in the mountain. You pay attention to the time — whether it's morning or night, whether the sun is setting and the guy has just eaten. So instead of just having the guy walking all the time, you know it's time for him to eat or to go to sleep, so you can get involved with the timing; I have a very good time doing that. And it's like I'm doing it all as I draw it. I know when everything's happening. If somebody else was doing the pencilling, sometimes they wouldn't follow what's going on, so they would always draw the same. But I try to pay a little more attention to a lot of details. I like to stay in a particular period. Groo don't exist; ergo, the place where he lives doesn't exist either. But even a nonexistent place has to have certain canons of logic. If he's in the period of swords, then there's no guns. If there's no guns, there's no powder. If there's no powder, there's no explosions. So, in the whole 51 issues, I have never used a gun nor powder explosion. See? Not only because I don't believe in guns, but because I don't think it fits. So I won't use it. Also, it would be the death of Groo. The death of the samurai was the arquebuse. Anytime somebody has a gun, what's a guy with a sword going to do? So I would never put guns in Groo. Everything has to fit. The animals. The architecture. But I can go from one period to another. I can have an almost medieval era, which feels very very comfortable to me — castles from the 14th, 16th centuries — and then cave-type people.

ARAGONES: Yeah. The looser humor is... You see, when I'm doing cartoons for MAD. I want to be looser. Sometimes I can't because MAD has very strict guidelines about drawing. But a cartoon has almost no background. It has to look very simple, like the Marginals. The idea's there, you don't have costumes, the guy's just dressed — if he's a fireman he has a little fireman hat. But the less you put, the easier it is to understand. But now I'm drawing a comic book. Everything I have been talking about for cartooning I have to totally disregard. Now I need environment. I need ambiance, I need costumes, I need continuity, I need directions for the characters to come in. And suddenly everything is different. It's two totally different jobs. The humor is in the content. The humor is in the characters themselves. But the backgrounds can be as elaborate as you want. And the more you put in, in my opinion, the better established the character gets. You establish where everything is: if he is in the desert, in the mountain. You pay attention to the time — whether it's morning or night, whether the sun is setting and the guy has just eaten. So instead of just having the guy walking all the time, you know it's time for him to eat or to go to sleep, so you can get involved with the timing; I have a very good time doing that. And it's like I'm doing it all as I draw it. I know when everything's happening. If somebody else was doing the pencilling, sometimes they wouldn't follow what's going on, so they would always draw the same. But I try to pay a little more attention to a lot of details. I like to stay in a particular period. Groo don't exist; ergo, the place where he lives doesn't exist either. But even a nonexistent place has to have certain canons of logic. If he's in the period of swords, then there's no guns. If there's no guns, there's no powder. If there's no powder, there's no explosions. So, in the whole 51 issues, I have never used a gun nor powder explosion. See? Not only because I don't believe in guns, but because I don't think it fits. So I won't use it. Also, it would be the death of Groo. The death of the samurai was the arquebuse. Anytime somebody has a gun, what's a guy with a sword going to do? So I would never put guns in Groo. Everything has to fit. The animals. The architecture. But I can go from one period to another. I can have an almost medieval era, which feels very very comfortable to me — castles from the 14th, 16th centuries — and then cave-type people.

THOMPSON: You can slide back and forth in time, in the same way that Prince Valiant's backgrounds are actually anachronistic, but they work because it's what readers think that period looked like.

ARAGONES: Yeah. You invent your own mythology.

THOMPSON: If it looks right, it works.

ARAGONES: And I think it works with Groo.

THOMPSON: When you have an incredibly elaborate background, how hard is it to direct the eye to the main figures? Is it something you do automatically at this point, or does it take a kind of thinking?

ARAGONES: Uh... I don't know. [Laughter]

THOMPSON: To me it's amazing, because you see these huge spreads with all these things going on and the eye goes naturally to the main characters.

ARAGONES: Well, that's composition. I guess you learn it through the years, watching the movies and thinking about how the directors led your eyes to that. Like the director of Lawrence of Arabia [David Lean], that guy can pinpoint a figure in the desert and you can see it. It comes through practice. Also, I don't do it all at once. See, I start here [indicating a penciled rough for a typical Groo spread, but with only the main figures inked in] and then 1 continue my regular drawing and inking. When I'm finished with the rest of the book and I have a little time and I'm tired, I take the big splash and start adding a little more. Or before I start drawing, or when somebody gets on the telephone, or if a television program is very interesting — then I pick a page that I have to do a lot of work on and I can just... play with it. So it takes me a whole month to go over those two pages, but if I did it all at once, it would be very wasteful because I would waste precious time I could use to finish this story. Like this, I don't feel like I have to rush it, so I take the whole month to work on it. What you do... First you draw that point of it and then you start to go around it [indicating a spiral going out from the central figures], adding here and taking off there. And it slowly comes out to be finished. And I juggle a lot because it's a lot of fun. Oh, when we were talking earlier about the process of doing the comic, I forgot to mention that once I finish drawing it it goes back to Mark, and Mark corrects again. He will read the finished story and get a kick out of it because he didn't see the drawings until they were finished and it's like reading a new story, just like when I got it back from Mark I laughed because there were a lot of little gags there that I didn't know were there. Then he corrects the language again. We're very careful about that. There are no spelling mistakes in Groo. And he always checks that Rufferto has his black eye, and then, when it's all finished, we make a Xerox and it goes to Tom Luth. Tom is such a good colorist that I don't have to give him any color schemes or anything. He knows exactly what he's doing. He's been doing it so long and so well that I have total confidence in his work. It is excellent. Once in a while he'll call me and say, "What is this, a puddle of blood?" — something that is not legible and he just can't solve. And from then on, I don't know what happens until I get the printed copy. And then it's, "Oh my God! They forgot to put color in Groo's hands!" and stuff like that.

THOMPSON: You must be the longest-running team of people to put together a comic book. Shortly, you’ll have done two thirds as many issues of Groo as Stan Lee and Jack Kirby did of Fantastic Four.

ARAGONES: Really?

THOMPSON: They only did 103.

ARAGONES: Ah, but did Kirby do pencil and ink?

THOMPSON: No. It was mostly Joe Sinnott.

ARAGONES: Well, maybe I did a hundred if we add up pencils and inks. [Laughter]

THOMPSON: That's true.

ARAGONES: No, but I do so little pencilling it doesn't count.

THOMPSON: Actually there was Jim Davis' Fox and Crow, which was also a single person. But anyway...

Europeans, Americans and Humor

THOMPSON: Groo’s always seemed to me more in touch with the tone of the European comics than the American comics. I think of a series like Lucky Luke...

ARAGONES: I'm very much influenced by the European comics, and the European artwork. I have, all through my life, read European comics and I visited Europe in the '60s. So, yes, as a humorous comic book artist, there's not too much work here I can draw a parallel with — only Barks's Donald Duck adventures, those fantastic worlds. But if we get into the context of European comics, there's so many of them. They are based on the same principles. They are comically drawn characters that do adventure, not funny stuff. So I feel very comfortable with the European market, or readership, or product that's coming out of the minds of Europeans, because they think like me. Many of them. In Pilote, half of the contents are humor. Groo in Europe is like one among a lot of them. It gets lost in the shuffle, which is fine with me. That means I belong to a particular genre, which is humor. And here I feel bad — like a sore thumb. A lot of the kids don't want to read it because they don't understand — they laugh if the super-hero is not correct. They are not trained for this type of material. It's very strange. I wish there was much more humor; Groo would fit very comfortably surrounded by the other cartoons.

THOMPSON: My theory is that American comics readers are mostly adolescents, who have no sense of humor. Kids do and adults do, but somewhere in the middle period there, I guess things aren't as funny.

ARAGONES: Yeah. As you say, I have a big very young readership; I have an adolescent readership, but not as big as the young one. And then I have the older group who really enjoy Groo a lot. I get a lot of mail, and it's in two parts: the people who are more grown up and can talk a little more seriously about humor, and the kids who love Groo as a character and talk about him and want him to do this and to do that. But children laugh. American audiences don't laugh in public. They are so used to getting their laughs in their homes, privately, through television, that people don't go to parties to tell jokes. See, in Europe, or in Mexico, where television is not so strong, the first thing you do when you arrive at a party is tell jokes. Because nobody knows them. You have heard a joke at your barber's or some- place, so you go to a party and you tell the joke. And then you laugh a lot. And then somebody else tells another joke related to that: you spend a lot of time telling jokes all over Europe. But here, if you're going to tell a joke, everybody read it or everybody heard it on Johnny Carson, so what's the point in repeating it? It's been said. And you've got all these professional comedians to tell the jokes; you don't have to bother telling them. Put on any comedy routine, and there they are, people who tell professional jokes better than your neighbor. You see?

So on that principle, there's not that many humor magazines. Very few. All the humor appears in the pages of other things. If you want sophisticated humor, you get it in the pages of The New Yorker — but as a supplement. If you want girlie humor, you get it in Playboy — another supplement. You want gun jokes, you get it with Sports whatever. Each cartoon comes as a supplement. There are very few cartoon magazines, just cartoons in magazines. People are not trained to read humor.

Comics have always had that stigma of being bad, or bad for children, and adults would never be caught dead reading a comic book in a public place. In Europe, comics are as normal as other types of literature, and you can see an architect or doctor reading it, and the boss in the subway. It feels normal. In Japan, also. But here...

THOMPSON: Do you think it's changing at all?

ARAGONES: Yeah. It is changing. People are getting a little less embarrassed about reading humor, but there's still not much humor to read. There'll always be this and that, but proportionately to other things — proportionately to super-heroes, how many adventure comics do we have? Not that many. Sable is adventure.

THOMPSON: Even so, it's super-hero adventure.

ARAGONES: Yeah, but still it's adventure and not completely super-heroes. But there's a very minimal percentage of humor comics. And then there is that strange area of cartoony humor vs. "serious" humor. See, you have a line that divides — in Europe, for example, we have Valerian: the adventures are very serious but the drawings are cartoony. We don't have any of that here. The cartoony characters have cartoony adventures. Groo adventures are cartooony, and Groo is cartoony. But we haven't had one serious adventure drawn in a cartoony style since Little Orphan Annie — or Dick Tracy. Those were serious stories drawn by humorous artists.

THOMPSON: Early Roy Crane, or Caniff.

ARAGONES: Early Roy Crane, absolutely, that was serious adventures done in a cartoony style. But Caniff was a serious artist. He had left the bigfoot style; his characters were realistic. They weren't jumping around with both legs going "YAHHK!!" You see?

THOMPSON: Dickie Dare and the very early Terry were quite cartoony, though.

ARAGONES: Oh, yeah; but I'm talking a little more contemporary. The divisions have been very clearly established. If you draw seriously, it has to be serious. And if you draw funny, it has to be very funny. You can't have a serious adventure drawn funny — which is what I would love to do. When I started T.C. Mars, the female detective I did for Sojourn, it was going to be serious adventures drawn funny. Don Rico, who was a very good artist, was writing some scripts for me, because we thought it was going to continue. It never did, so we never sold those stories. But he also started writing humorously. I said, "No, no, no. I want it written as if you were writing for a regular character; then I'll draw it funny." It's very hard for a people to see a humorously drawn character behaving seriously. It happened before in the comic strips and it can happen in the comics.

THOMPSON: In a certain way. isn't Maus that?

ARAGONES: Yes. But again we're talking percentages. We go back to that one example. In the undergrounds we had it constantly. On one hand, you had the Freak Brothers doing funny stories, but on the other hand you had Binky Meets the Virgin Mary. There was a very funny drawing with a very serious subject — his [Justin Green's] personal traumas and stuff. The underground would take very serious stories and tell them with funny cartoons. Crumb!

THOMPSON: Of course.

ARAGONES: But again, it was underground. In the overground we can't have that. I don't know who will break the barrier. And it's important to break it. The more variety you have in comic books, the better for the public.

Dollars and Sense

ARAGONES: But now we have to talk about economics, because everything is based on economics here. We have a system of books or bookstores that are so mechanical. Everything is so pigeonholed: you have to have a specific product to go to a specific place so it can be specifically sold to specific readers. And this is very bad when you want to play with something. Because they don't know what to do with it.

THOMPSON: Maybe that's why all the graphic novels wind up in the humor section.

ARAGONES: I wish they did. But they don't even do that. It would be a terrific place for Groo. The graphic novel is a very good idea. It's what Eisner has been drawing and what that gentleman who did The First Kingdom...

THOMPSON: Jack Katz.

ARAGONES: ...Jack Katz wanted to do. He wanted to take a comic and put it in a very serious format, rather than a regular format. And a lot of people started saying, "We're going to get out of the comic book shop. And we're going to go someplace else." Well, it didn't happen like that because the big companies are there for the money; they are businesses and we have to be very realistic about that. Business is not a place to have fun. Business is there to make money. Business has a responsibility to the people who invest in this particular business. So a business has got to do what is good for the business. But if you don't have somebody with creativity in the business, you're not going to improve the business very much because the business will concentrate on what's good in the short term. But without any regard for the larger point of view, of what is going to happen 10 years from now. So those are not visionaries; they're just accountants who want to make money for the next quarter. And they're very happy because their accountants make more money like that, but in four years they have to get out of office and [claps] that's it. They leave their job. They did their job.

But they didn't really do their job. They screwed up the magazine or the company because they didn't look to the future. In Japan, companies look to the long term: they go slowly, slowly, slowly. The Americans build up a company in a very short time and suddenly POOF! they collapse. And the Japanese keep going and 10 years later, they own it. Why? Because business also have to do with vision. In the comic books it's the same thing. The people who are doing the comics have no vision. They do the graphic novels. [Claps] "We can sell them all in the comic book shop! There's all these little kids that buy everything that we put out." The graphic novel goes into the comic book shop and that's it. You don't see it in the big stores. Why? Because the big store doesn't know where to put it. The graphic novels are very thin. They look like comic books. And they don't fit in the rack with the comic books. So they don't know what to do with them. So they don't sell any. They don't want them. They are a pain in the neck. They are too esoteric. They don't have a particular subject. They don't know where to put them.

If you had a little more vision, you'd say, "Well, we have to start opening the market. Let's not be mercenary and try to sell the whole print [run] immediately in the comic book shop. Let's look into the future." What do we need? Compartments. If we do a graphic novel in science fiction, we should make a point that the bookshop puts this graphic novel in the science fiction department. Because the people who love science fiction are going to go to the science fiction pigeonhole and are going to see that graphic novel there and they're going to buy it because it's good. And if it's no good, they're not going to buy it. But now you can't blame it on the system. It was a bad graphic novel. The humor goes in the humor department. Adventure goes in the adventure department. Comic book heroes? They don't have a place in the graphic novel. They are comics. They go into the comic book department. But if you want to do Stray Toasters — a good graphic novel: good art; good writing — give it a name. Is it science fiction? Is it fiction? It is science? Let's put it wherever it fits. Don't try to invent a new category, because it doesn't exist. In the future, when each one is in their place, you can create a new category called "graphic novels" and put them all together. But right now, there's no place like that. So you have to think a little more in the future — more than the immediate money. See, the graphic novel is a great solution. But then they make The Hulk into a graphic novel. If you wanted to put that in a book store, where would you put it? In the humor department? It's not humor. Are you going to put it in the history books, or research, or what? So this is a problem. You have to sit down there and study the problem with a little more vision to figure out specific market.

THOMPSON: There was a period, right after Dark Knight and Maus, when ati the publishers thought that graphic novels were the next big thing. They put out a lot of projects that failed, and now they're retrenching again.

ARAGONES: They do that with almost everything. Maus got a lot of publicity because it's a book that has a value in itself. Its value has nothing to do with comics or novels. It is one's man work, and a very good work. So that can fit wherever they put it. They don't put it with comic books. It's a fiction book and it goes in fiction. It's just an illustrated fiction. They don't think of it as a graphic novel. And it's a matter of opening the market up. We can sell no more comics if there's no more market. The comic book itself has discovered the comic book shop. We are not going to sell more comic books until they open more comic book shops. It's not going to get out of the comic book shop. Supermarkets can't carry them.

Animation

THOMPSON: How did you get into animation?

ARAGONES: Well, I've always liked animation. I've read a lot of books about animation, and I never really separated cartoons from any of the other things I do. All the fields are together. What you learn about cartooning, you learn about animation. When I was in high school, my father was in the movie industry. He was producing a movie called Santa Claus in Mexico. And the director of the movie, Rene Cardona — he's a very good director, has directed a lot of movies — his son was a very entrepreneurial guy. One day we were talking about Santa Claus; we'd heard that they were going to need some animation, so his son, who was even younger than I was — and we're talking high school — decided that we could do the animation. Because I knew how to draw and he knew how to shoot it. We had both read the book by Preston Blair, How to Animate. I said that it couldn't be done and he said that it could be done. So my father said that if it was good, he'd buy it from us. Between his father and my father, they gave us the money, so we build all the equipment. We built the drawing table and I drew hundreds of cels — hundreds and hundreds. I spent a whole winter vacation — in Mexico, you have a winter vacation instead of summer vacation. So I spent a whole week of drawing these Santa Clauses, with reindeer walking around and everything. Well, it was so poorly done that there was no way they could ever use it. But it was a great experience. I learned how to animate just by doing it. We had to cut our own cels and everything. It was the hard way to do it, but I learned a lot about it and I just liked it a lot. And when I was here in the States, I was called by George Schlatter. He called me as a writer to do some writing for a show called It's a Wacky World. And during the conferences I did some sketches which were used for the animation on that show. I'd done some animation before, but I would always design the characters and hire a studio to do it. Then, when I did Laugh-In for him, I hired a young man from UCLA to be my assistant, but he was such an expert animator I was learning from my assistant. [Laughter} His name was Hoyt Yeatman, and he's the boss at Dreamquest Studio. He does a lot of special effects for a lot of big studios. I had carte blanche with George to do anything we wanted to do. They were doing six one-hour specials, so whatever I wanted to learn, I asked, "Hoyt, can we do this?" And he'd say, "Yeah!" So I would write a storyboard for a piece we needed, George would approve it and then I would learn how to do it. So we did all kinds of things. We did front screen projection, we did pixilation, we did people with puppets, puppets with people, animation with puppets. Everything that could be done with animation I learned there, and I learned by doing it.

And even before that, I wrote storyboards for Jack Mendelsohn when I was in New York in the '60s. So I've always been involved in it in one way or another. And when they did TV Bloopers and Practical Jokes, they called me to do the animation and I did a few in the beginning all by myself. But I always have a Mark Evanier: I had an animator who would correct my cartoons, put in the right timing. For TV Bloopers and Practical Jokes I had Lee Mishkin Studios. He's a very good animator; he did them all in his studio himself. But you get into animation like you get into comics.