All too often we wish we asked our parents questions about their lives, had gotten the full story of how they came to be individuals who then brought us into the world. There are an infinite number of books (too many to count graphic novels) about progeny trying to come to terms with the history of their parents. It is rare though to get a complete story from the horse’s mouth and that is exactly what graphic novelist Joey Perr was able to do. After one long summer of living at home after college at the time high-school teacher Joey Perr decided he should learn more about his father, Herb Perr. Herb had lived a crazy life filled with pretty-gangsters, famous artists, and many different versions of New York City. The ensuing project that resulted in Hands up, Herbie! took six years. It began as a comic zine, expanded into a two-hundred page graphic novel, and took a successful kickstarter to bring the graphic novel into print. Hands up, Herbie begins under the elevated train tracks of Brighton Beach, the reified art world of Manhattan, and ends up back in Brooklyn. Throughout the book we learn just how hard it is to untangle yourself from family. I sat down with Joey to discuss the great Herb Perr, the process of creating the graphic novel, and how it fits in with the immigrant stories we tell ourselves.

All too often we wish we asked our parents questions about their lives, had gotten the full story of how they came to be individuals who then brought us into the world. There are an infinite number of books (too many to count graphic novels) about progeny trying to come to terms with the history of their parents. It is rare though to get a complete story from the horse’s mouth and that is exactly what graphic novelist Joey Perr was able to do. After one long summer of living at home after college at the time high-school teacher Joey Perr decided he should learn more about his father, Herb Perr. Herb had lived a crazy life filled with pretty-gangsters, famous artists, and many different versions of New York City. The ensuing project that resulted in Hands up, Herbie! took six years. It began as a comic zine, expanded into a two-hundred page graphic novel, and took a successful kickstarter to bring the graphic novel into print. Hands up, Herbie begins under the elevated train tracks of Brighton Beach, the reified art world of Manhattan, and ends up back in Brooklyn. Throughout the book we learn just how hard it is to untangle yourself from family. I sat down with Joey to discuss the great Herb Perr, the process of creating the graphic novel, and how it fits in with the immigrant stories we tell ourselves.

Sam Jaffe Goldstein: Herb, your father, has an incredible life story. Was there a story that he told you that compelled you to begin this book?

Sam Jaffe Goldstein: Herb, your father, has an incredible life story. Was there a story that he told you that compelled you to begin this book?

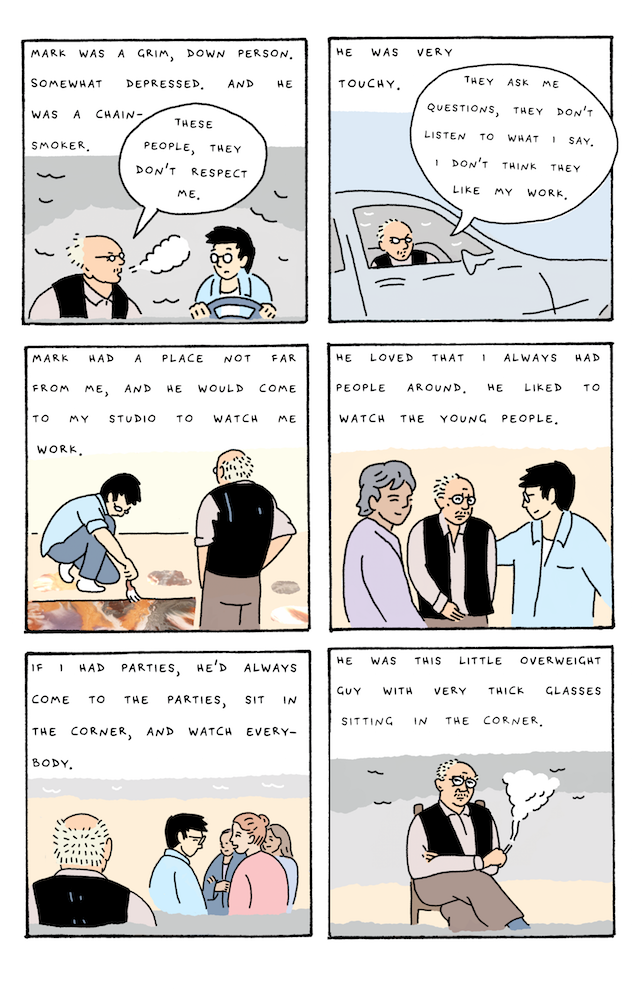

Joey Perr: I had ideas about my father’s childhood in Brighton Beach, about his career as an artist. But no, I didn’t grow up hearing too many of Herb’s stories, at least not in such detail. My father lived in the present tense. He did not have a happy childhood and went to great lengths to distance himself from his upbringing. Living in “the now” was probably a coping mechanism. For most of his life, the “now” was far more interesting and satisfying than whatever came before. In the book he tells me, “I always looked forward,” and it really was true.

It’s not that he wasn’t willing to talk about his childhood—no subject was off-limits for Herb—he just never went into so much detail when I was a kid. But some outline of my father’s childhood came into focus through comments, asides, and facts stated plainly. I knew he grew up in Brighton Beach in the forties and fifties. I knew from photographs that Herb’s father, my grandfather, was a gangster-type. There are pictures of him surrounded by the likes of Red Levine, Bugsy Siegel, and other Jewish gangsters involved in Murder Inc. I knew that my grandfather ran an illegal gambling racket out of the back of a candy store under the Brighton Beach elevated train tracks. If I was upset about something when I was a kid, Herb would relate to me by saying how lucky I was, because when he was my age he would go to bed hungry, and he never knew where his father was, and once he didn’t come home for two years. If Herb lost his temper, he would tell me afterwards that his own father was full of such rage I wouldn’t believe. That his father was always getting into fistfights with people, including the repo men who came to collect. He’d tell me that he hated his father. But then other times he would tell me that I was a lot like his father, and that his father would have loved me. He told me that he moved out when he was fourteen, and paid his rent by selling knishes. These weren’t stories, they were just facts. So I was always curious about his life, I wanted to piece it together, but I had to work myself up to asking him.

When did he start to tell it you more fully?

After graduating from college I lived with my parents briefly, and I had a hard time relating to Herb. We weren’t getting along. So as soon as I moved out I made a plan with him to go out to lunch, and I asked if I could record some of his stories. It just seemed like a good way for me to get to know him a little better, to have a reason to spend some time together. I did not know it was going to be a comic, I just wanted to get the stories down. So, we went out to lunch, and I asked him to tell me about when he moved out of his parents’ place. I was thinking about how he’d moved out when he was fourteen, but he immediately starts talking about leaving Brighton Beach when he was eighteen. For him, that’s when his life started, when he left Brighton Beach and cut ties with his family. But I said, “Let’s start with the first time you moved out, when you were fourteen.” He told me that it wasn’t going to be that interesting, but sure, and he just opened up. He spoke for a couple hours about his father and why he couldn’t live at home anymore. I recorded the whole thing, went home, transcribed it, and then I called to ask if he would meet me again the next day. We met up almost everyday that first summer. He started calling me up because he remembered something else, or to say that he wanted to talk about a particular thing next time.

The book covers almost all of Herb’s life story. Why did you decide to include all instead of just a part of his story?

The book covers almost all of Herb’s life story. Why did you decide to include all instead of just a part of his story?

When I started these interviews, it was just to have a record of my dad’s life. But the more we recorded, the more there was to record. He wasn’t telling me these stories in any particular order. So the fun was in finding the narrative, by transcribing the audio, figuring out how to arrange the stories, going back to Herb to flesh out the gaps. The best part was showing Herb how the stories fit together, because he didn’t see it. He’d preface his answers with, “I’ll tell you this, but you’re not gonna wanna use it,” and it turned out that was code for, “Here is something absolutely essential you wouldn’t dare leave out.”

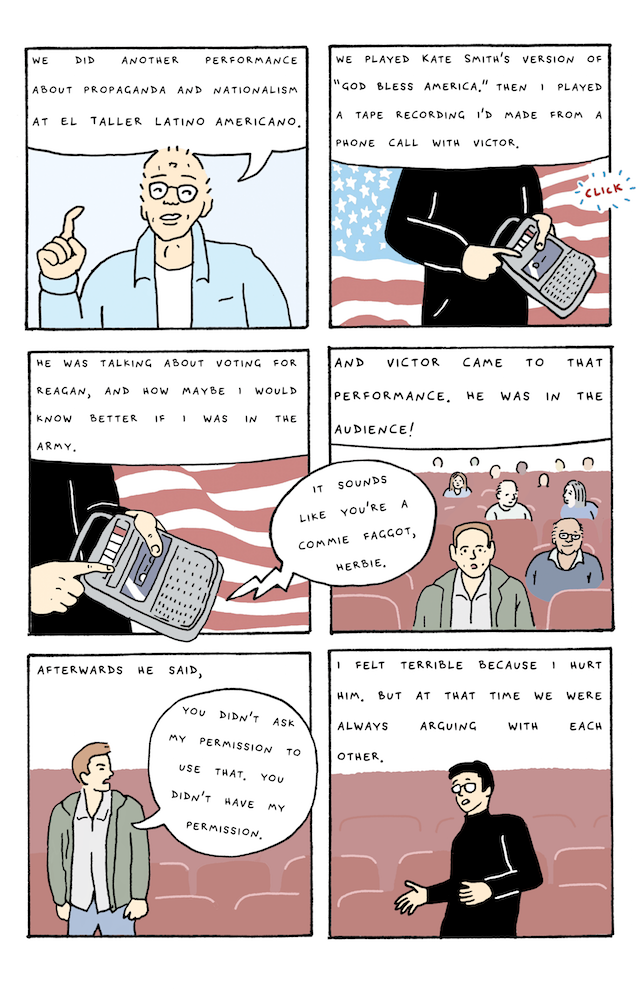

I finished first first sixty pages of the book and I thought that was going to be the whole book. That is part one of Hands Up, Herbie!, which ends with Herb leaving Brighton Beach in 1959. But there was so much more to the story. I had more questions, I guess I didn’t want to give up the routine of interviewing Herb. And for Herb, leaving Brighton Beach was when his life became interesting. That’s when he made a life for himself as a painter and a teacher. But while we’re working on this second section, Herb’s younger sister Susie died after a lifetime of substance abuse. Herb was really shaken by Susie dying. One one hand, he felt like he’d done as much for her as he could, and on the other, he was wracked with guilt at not having been able to do enough. Two months later, Herb’s older brother Victor died. So naturally we start talking about his siblings, and it turns out that it was not so easy for Herb to break away. Family kept pulling him back in. And this section felt crucial, because I didn’t want to create a mythology about this artist’s self-emancipation. But in part two, we ended up telling a story of Herb’s adulthood without ever talking about his career as a painter, and that was the next section.

I was still eager to talk about his life as a painter because that was just as fascinating as the mob stuff: as a student, he’s taken under the wing of the painter Helen Frankenthaler; he works as an assistant to the painters Robert Motherwell and Mark Rothko; he is represented by a big name gallery and has work in the Whitney Museum. But the whole time he’s skeptical of the whole scene. He turns down the gift of a painting from Rothko. He stops showing in galleries, because he’s becoming more political. He comes to see the mainstream art world as a capitalist enterprise as he becomes involved with political artists and writers like Lucy Lippard, Amiri Baraka, Ana Mendieta, and so many others.

Herb was witness to so many different things: Brighton Beach of the forties and fifties, downtown Manhattan and the art world of the sixties and seventies, political art in the eighties. Each of these sections is a slice of New York at a particular moment. And I loved seeing how Herb moved through it all. I wasn’t trying to include every detail, but there was a larger narrative to uncover and then to pull together. To tell just one part of this story wouldn’t have been nearly as interesting, at least not for me.

Let’s hear more about when and why Herb turned his back on the artworld.

Let’s hear more about when and why Herb turned his back on the artworld.

My dad wasn’t a big compromiser. When Herb moved from Brighton Beach to the Lower East Side, it was this huge intellectual awakening for him. He was just taking it all in, and there were some contradictions. He joined Marxist study groups while striving for personal success in the galleries. One time, Helen Frakenthaler invited Herb to her studio to meet David Rockefeller, who was coming by to pick out a painting. So he spends an afternoon shmoozing with Helen Frankenthaler and David Rockefeller, all the while thinking how strange that half of his life is learning about class struggle, and the other half is navigating this market-driven art world. The last straw for him was when gallery owner John Bernard Myers gave Herb a hard time about changing his style, artistically. John said that the collectors were complaining that he is devaluing their investment by changing his style. Herb thought that was bullshit, and stopped showing his work in galleries.

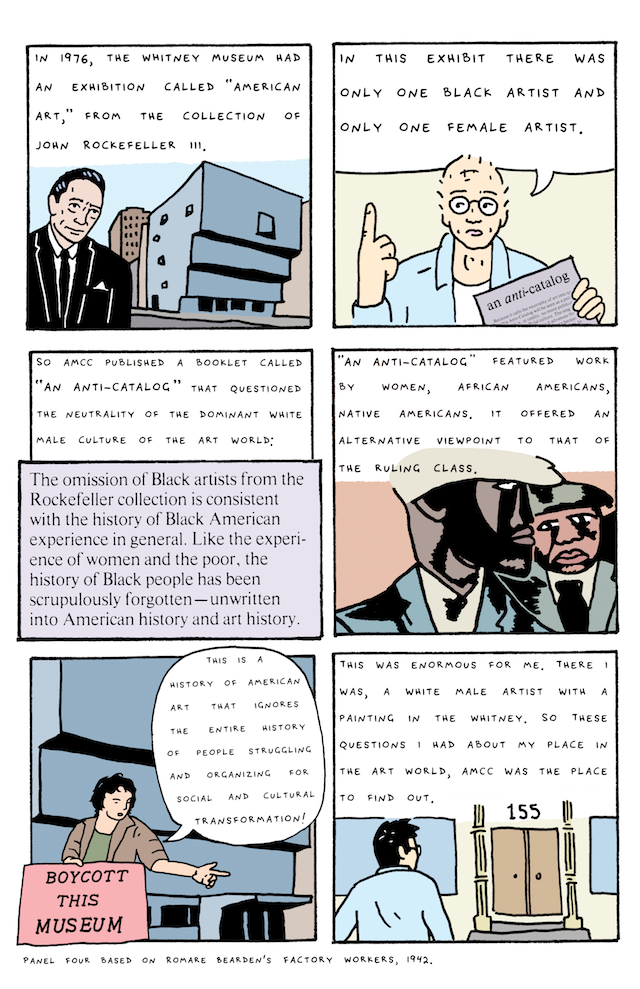

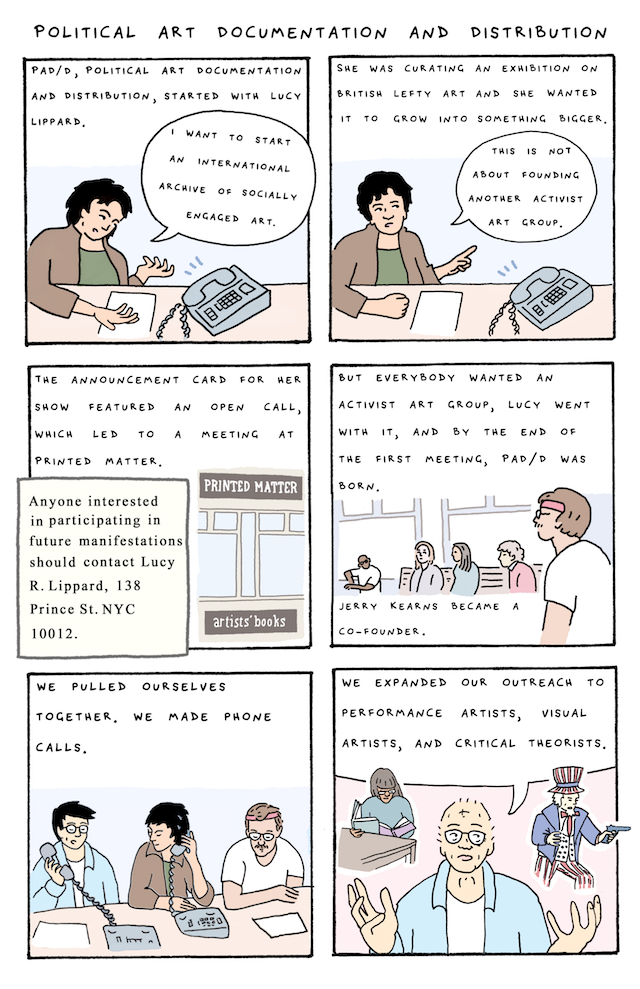

This incident overlapped with Herb joining a group called Artists Meeting For Cultural Change, whose goal was to challenge the status quo of the art world. Herb felt that the gallery scene was too focused on celebrity, and was drawn to the idea of artists taking collective action to change the culture of the art world, as well as the culture at large. AMCC fell apart after a few years, but the experience was so formative for Herb, and that was where he met the artists with whom he would co-found the group Political Art Documentation and Distribution, including the writer and curator Lucy Lippard, who had a particular influence on my dad. PAD/D was intended to be both an archive of political art, and a forum for artists to relate to social movements. So this is where Herb was able to doing work that brought together all the different threads of his life, work that was politically and artistically meaningful. And for the first time in his art, he was encouraged to explore how his fraught upbringing led him to become a leftist and an artist.

Your dad escaped in part thanks to the cheapness of rent and funding for arts education. He doesn’t seem to have nostalgia for Brighton Beach, but did he talk about what he would have done if didn’t have those resources at all?

He even says, “I don’t know what I would have done if I didn’t get a full-scholarship to NYU.” Herb did have a knack for finding people who gave him the support he wasn’t getting at home. The book is full of people who saved my dad’s life: the twenty-five-cent-an-hour therapist he found in the yellow pages, his art teachers, even the local “pederast” who bought my dad winter coats. Once I made the mistake of telling him that it was a little easier back then: he had this full art-scholarship, rent was cheap, and he went from poor to middle class very quickly. But he just stared at me with this face like he’d seen a thousand ghosts and said it wasn’t easy at all. He never thought it was easy, despite his optimism, which really served him well and endeared him to people. He never got over his childhood. So we can say, there was a lot more funding for the arts at that time, rent was so much cheaper, but that given the circumstances of his childhood, it wasn’t a given that my dad would make it out. His younger siblings did not do as well as he did: his sister became a prostitute and a drug-addict, his younger brother has dealt with addiction his whole life, and Herb felt a lot of guilt around his own success relative to theirs.

In the beginning there are panels of Herb saying, “I don’t know if you want to put this in there” and “Next time I’ll tell you about your great-grandfather’s Seders.” That editorializing is distinct in the beginning and then disappears. Was that a conscious choice, or did that happen because the reader now understood the beat and rhythm of your dad?

A combination. Every story in part one of the book Herb prefaced with, “I don’t think you are going to want to use this, but I’ll tell you anyway.” Because the early stories were painful and difficult for him, he didn’t see how they might appeal to anyone else. But when I left him an early version of the first section, my mom called to say that he was reading it on the couch and laughing out loud. He didn’t tell these stories in a linear way, he didn’t see the narrative I saw until I arranged it for him. So the disclaimers sort of stopped when he saw what I was doing. The second section of the book was probably more painful for him to talk about because it was about his siblings’ drug abuse. However, by that point we had gotten into the flow enough that he just trusted I was going to pull something out of it.

Did his nostalgia ever kick in?

Herb wasn’t sentimental, and he had no nostalgia about his childhood. But he had a great sense of humor about his childhood. If you have survived a thing, you can make it funny. He was eager to tell me a funny story about his uncle Pete’s suicide. Pete’s suicide was a tragedy for the family, but Herb wanted to tell me about the one thing that made him laugh: his aunt Chippie was a neat freak and had vinyl all over the furniture. Whenever my dad would come in from the beach she would go, “Hands up Herbie! Let me see those hands!” and inspect them. One day, uncle Pete comes in, goes upstairs, and shoots himself in the head in the bedroom. And what goes through my dad’s head is “Wow, that must have been really messy, there wasn't any vinyl on the bed or anything!” Incidentally, when I repeated that story to my uncle Harvey, he wanted to share another funny story about Pete’s suicide, that whenever he would sleep over, Chippie would put him in their old bedroom, which still had a big blood stain on the wall! The Perrs were not a nostalgic family.

Herb wasn’t sentimental or nostalgic, but he wasn’t ashamed either. Any one of his childhood memories could be considered shameful for a family. People don’t know how to talk about a suicide in a family, it’s hard to talk about a relative in jail, a gambling problem, or an abusive father. Herb was able to talk about it with no shame. But he worried that I might be! Once he said to me, “What are you going to say, “that this was your father? That this is your family?” I said, “Of course.” He said, “Then everyone’s going to know.” But I asked him if he cared, and he said, “No!”

Talk about the process of making the comic. You would interview your dad, then you would transcribe it, how would you then take that transcription, edit it, and lay out text over drawings?

Talk about the process of making the comic. You would interview your dad, then you would transcribe it, how would you then take that transcription, edit it, and lay out text over drawings?

Editing the text was the best part for me. Some of the book’s chronology is thematic, it will bring you up to a point, and then the next section will go back in time a bit. I would figure out which section a story belonged in, then where it should be in the narrative of that section. I always got the script of each section together before drawing it. I would lay out the text across panels, and that was where I would see if a piece of text was redundant or if I needed Herb to say something more. A lot got shaved down when I laid the text into panels. I always laid out the text before drawing.

Why did you take yourself out of most of this book? Both the conversations with your dad and then the work of transcribing it are not here.

That would be another book. When I put together the transcripts of these interviews, I didn’t know that I was going to illustrate them. I wanted these stories recorded. I had Studs Terkel's interviews in mind, where he would remove himself entirely and create these monologues of his interviewees. I wanted a document of Herb’s life, in Herb’s words I still think that his life is interesting enough without me as a character me figuring it out, like Maus or Jeffrey Lewis’ interviews with his dad in Fluff. And I liked writing as my dad. I really identified with his voice. I felt comfortable writing stuff that I couldn’t get him to say, and so was he. He was always telling me to “make it sound better.”

The way this book changed our relationship, which it did, I couldn’t translate into the comic as I was making it. We became so close working on this book. Our way of relating to each other changed. He started to open up to me not just about all these stories, but about everything. Things just got a lot easier between us. ‘

You are drawn as him and he is drawn as you in the book. Was that conscious?

You are drawn as him and he is drawn as you in the book. Was that conscious?

That’s partially because I’m identifying with him and partially because we look so similar in our thirties. There are only so many ways to draw a dark-haired person with glasses.

There are very few panels without anyone talking or no people. Is that a reflection of your own style or Herb’s style of talking?

A little of both. I got more comfortable later in the book with letting the pictures do more than the words. I started this over six years ago. If I were to start now, it would look very different. I learned how to make this book while making it. Throughout the book I kept finding my style naturally changing, and having to rein that in, a little. You can’t change your drawing style halfway through illustrating a two hundred page book.

Why not?

You want your characters to be somewhat recognizable throughout. And the reader gets used to the pacing of the story. It’s a straightforward narrative, I didn’t feel like there was room to change the pace or the style without explaining it, and the only explanation would be that I’m better now than when I started. I learned how to do this while making it.

Both Frank Santoro’s Pittsburgh and Jerry Moriarty’s Whatsa Paintoonist? are about coming to terms with a familial past and both use painting, full page spreads, collage, and they both feel a little like scrapbooks. Your book is almost a pure movement through time.

My drawings and layouts are pretty simple because I was so new to making comics when I started this book. It really helped to have a simple structure. I learned from reading Lynda Barry and Gabrielle Bell—although what they do isn’t simple at all—that it was okay to fill the top third of a square panel with text. In this book, to me at least, the text is far more important than my drawings. Towards the end I knew what I was doing within this structure, and I felt a little constrained by the structure.

I love the scrapbook aspect of Nora Krug’s Belonging, which moves between photos, drawings, and letters. I wish I had given myself more leeway to experiment in that way. In the last third of the Herbie I do start including a lot of his paintings, some Helen Frankenthaler’s work, and the work he did with PAD/D as collage. But it’s within this very rigid structure.

There is a long history of Jewish graphic novelists writing books growing up in New York City or their relationship with their father. How do you want this book to reflect that tradition?

There is a long history of Jewish graphic novelists writing books growing up in New York City or their relationship with their father. How do you want this book to reflect that tradition?

I don’t know how it fits into the world of Jewish graphic novelists exploring their history, making “pop art,” as Art Spiegelman calls it, except I guess that that’s what I am in making this book.

But this story fall outside the Fiddler On the Roof immigration narrative. This is not a story of immigrants coming to America and having a great time. It’s a story of immigrants coming to America and their children becoming gangsters, which was a tragedy for my great-grandfather. One of his sons ends up in prison with a life sentence, the other son kills himself, my grandfather was always in and out of jail and on the run. My dad had to immigrate out of his family. His family does not have that upward trajectory of the standard immigration story of American Jews, so he leaves them behind.

But this isn’t an atypical story. This kind of story is far more common than what is reflected in Jewish-American literature. I’ve heard back from a number of people in my dad’s generation who said, “Oh my God, my family was involved in the Jewish mob. They were petty criminals. They were gamblers.”

Did you feel a catharsis at the end of this project?

I completed a version of Hands Up, Herbie! two years ago, read the whole thing, and put it in a drawer. I didn’t know what to do with it. It was the beginning of Herb’s illness when I finished, and it had become much harder to work together on the project. But when he died two years later, I had this document of his life. So I applied myself to editing it and making it as good as it could be without re-writing and re-drawing the entire book. Working on the book in the months after he died was was a part of grieving, and of staying connected to him. I was still writing in his voice, I was still identifying with him, he was still here encouraging me to finish it. And when there was no more to re-work, when I had a finished version of the book, I didn’t have an outlet anymore. I came down with shingles the week I finished. It’s satisfying to hold the book, but I have a hard time reading it now.

Have the stories you tell about your family changed now that you have finished the book?

Now I have a context for my family. I have an explanation for why my dad was the way he was. He was crazy in the ways he was crazy because of the way he grew up. This helped out relationship enormously while he was alive. Behavior that would have once bothered me, it no longer bothered me. I had a lot more empathy for him. It gave me a sense of where I fit into my family. Since this book has come out, friends keep telling me that they are eager to interview their family as well, for the same reason. To know what made their parents, to have a sense of where they fit into their family, the culture, history. I highly recommend it. Go interview your family.