While Dharavi is bang in the middle of Mumbai, this is not the main reason that the neighborhood is considered one of the city’s vital organs. One hears Dharavi described as the city’s heart. But it was more as Mumbai’s liver that Dharavi rose to power.

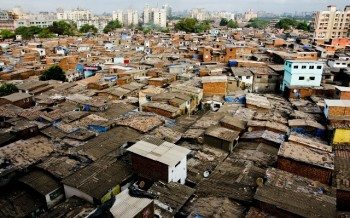

Originating as a Koli fishing village along the south bank of Mahim Creek, Dharavi in its modern incarnation as “Asia’s largest slum” emerged in response to Mumbai’s rapid growth in the mid nineteenth century. As the booming textile industry swallowed up the city’s south and central regions, Dharavi, whose northern location was then considered far-flung, served as a multifaceted dumping ground. Immigrant laborers poured into the area, leading to a rapid increase in substandard and oftentimes illegal residential arrangements, with no infrastructural planning to speak of. Dirty and heavily polluting industries congregated there: first slaughterhouses and tanneries, later pottery kilns and noxious recycling operations. While the acreage of the rest of Mumbai increased thanks to organized land reclamation projects, Dharavi’s did so as the swampy banks of Mahim Creek solidified with waste from the city’s many construction sites. During Mumbai’s era of prohibition (the 50s and 60s), Dharavi kept drinkers happy with its illegal, rotgut distilleries. If you are a politician or gangster and wished to fashion an empire, traditionally Dharavi was an ideal place to establish a voting bloc, recruit minions, and launder money. Real estate wolves (a.k.a. developers) also patrol these woods.

Politicians and planners were keenly aware of the growing mess as early as the 1940s. But as Liza Weinstein explains in her book, The Durable Slum: Dharavi and the Right to Stay Put in Globalizing Mumbai (2014), they had good reasons for doing essentially nothing about it. Not only was government focused on other parts of the city; they considered Dharavi’s “informality” a solution rather than a problem. “Slums proliferated and spaces like Dharavi grew,” explains Weinstein, “because they helped address the city’s growing need for industrial spaces and worker housing, with minimal public- or private-sector expenditure.” In this, Dharavi became a model for Mumbai. “Through a strategy of ‘supportive neglect,’ the local state allowed illegal businesses and housing to proliferate and become the norm across the industrial metropolis.”

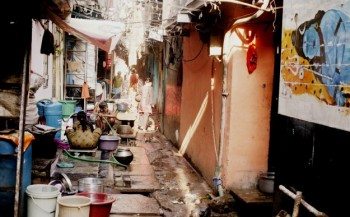

The novel ways in which Mumbaikars have responded to this situation have provided extensive fodder for PhD research and university think tanks, especially under headings like “the right to the city” and “spontaneous urbanism.” A more pedestrian term regularly applied to Dharavi is “microcosm,” with an emphasis on diversity and compression. Though less than one square mile in size, Dharavi is home to an estimated 500,000 to 700,000 people, representing every state in India. Resident industries and trades are mind-bogglingly various. With just a little effort, you can find a baker’s oven surrounded by sweaty men, butchers selling every part of the goat down to the hooves and eyeballs, drying papads down an alley from drying terracotta pots, men crammed in a room making leather handbags above women crammed in a room packaging them for shipping, or a ten-by-ten space housing a small metal foundry casting buckles and badges. Every category of waste is salvaged, sorted, and resold in Dharavi. Welders work in the street. There is no zoning in Dharavi. In many cases, the separation between residential, commercial, and industrial space simply does not exist. That could be said for a large swatch of Mumbai. The difference in Dharavi is the degree of intensity.

While Dharavi may be sexy as an object of study, daily life there is decidedly not. Negotiating informality means having to frequently bend the law, invest in graft, and weather petty power politics. Access to water is highly restricted, and until recently required kilometers of trekking and hours-long wait in a queue, unless you could afford to have a pipe illegally linked to the city’s water mains and snaked to your home. The infamous open sewers are now largely covered, but still the canals and the creek are choked with trash and have that syrupy green consistency that breeding dengue mosquitoes love, never mind the smell. Overcrowding not only means little privacy, but a high rate of infectiousness, most problematic these days being tuberculosis and swine flu. Pollution from Kumbhar kilns and plastic recycling guarantee a high rate of respiratory problems. Lack of toilets not only force women to uncomfortably hold it in during the day, but also leave them vulnerable to peepers and physical assault. Men here can be as conservative as anywhere in India. In some cases, wives and daughters are not allowed to leave the house without the man’s permission. Alcoholism and domestic abuse often go hand in hand. Things are slowly improving and there are many success stories. But even the uninformed skeptic probably assumes (correctly) that the happy ending of Slumdog Millionaire (2008), shot largely in Dharavi, is a pretty little lie. The poverty, the scrappy industriousness, and the underworld links have become clichés through the many Hindi films set in Dharavi, but at least that mythology is based on common realities.

Why am I telling you about this place? Because recently Dharavi midwifed an interesting comics project. There are more than a hundred NGOs active in Mumbai’s slums, engaged in issues ranging from tenancy rights and access to potable water to literacy and social tolerance. The one that concerns us is SNEHA (Society for Nutrition, Education, and Health Action), based primarily in Dharavi and dedicated to women’s and children’s health. According to the organization’s website, “SNEHA targets four large public health areas - Maternal and Newborn Health, Child Health and Nutrition, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Prevention of Violence against Women and Children. It recognizes that in order to improve urban health standards, its initiatives must target both care seekers and care providers. It works at the community level to empower women and slum communities to be catalysts of change in their own right and collaborate with existing public health systems and health care providers to create sustainable improvements in urban health.”

As part of its programming, SNEHA has conducted a large number of art workshops. These Art Boxes, as they call them, typically pair “mentor-artists” with local women, children, and young adults, with additional guidance from health professionals and social workers. The first major public presentation of the products of these workshops was Dekha Undekha (Seen Unseen), held in a small space in Dharavi in 2012. More recent, and much larger, was the Alley Galli Biennale, which was spread across multiple venues in Dharavi for three weeks this February and March. Its nickname, the Dharavi Biennale, seems to have been intended as a cheeky jab at the art world, which in India, more totally than most places in the world, is defined by class. While the Biennale’s ostensible primary aim was to raise awareness about public health amongst Dharavi’s residents, for an art world outsider it offered a demonstration of what the democratization of art (which the art world has paid lip service to for decades) looks like if seriously pursued.

Funded by The Wellcome Trust in London and curated by Dr. Nayreen Daruwalla and Professor David Osrin, two health professionals working for SNEHA, the Dharavi Biennale set as its task the following: “to combine art and science, to highlight the contribution of the people of Dharavi to India’s economic and cultural life, and to share information on urban health. The Biennale invites Dharavi residents to meet, educate themselves on urban health, learn new skills, and produce challenging artworks. It is a collaboration between artists of all kinds, scientists and activists to develop locally resonant artworks that are authentic, honest and relevant.”

The Biennale compromised more than fifteen workshops and involved more than three hundred Dharavi residents. The mentor-artists who led the workshops included writers, filmmakers, painters, and designers. Here’s a taste of the work produced. The Art Box “Hope and Hazard,” led by Nitant Hirlekar and addressing occupational hazards, resulted in a sculptural installation of stacked empty cooking oil canisters, on which were pasted digital print-outs of pottery, glass recycling, and plastic recyclers. “Immunity Wall,” guided by sculptor Fatema Jaliwala, presented mildly grotesque wall-hangings constructed out of scrap fabric and plastic on the theme of germs and the body’s immune system. They made me think of the recycled junk assemblages from the famous Yomiuri Independent exhibitions (Tokyo, 1957-63), which were likewise premised on the democratization of art practice (in a limited way), and whose participants were in many cases responding to the fallout of development and urban environmental pollution.

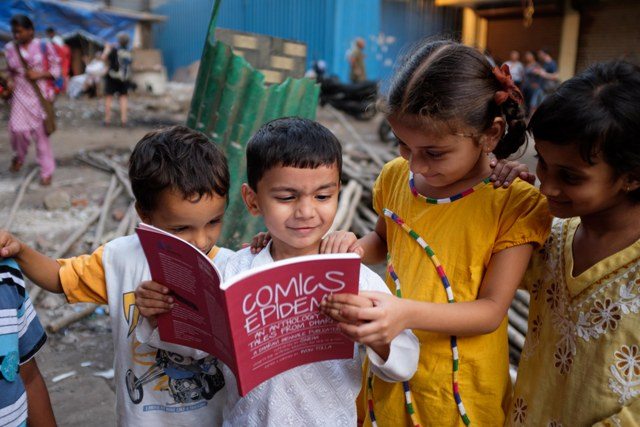

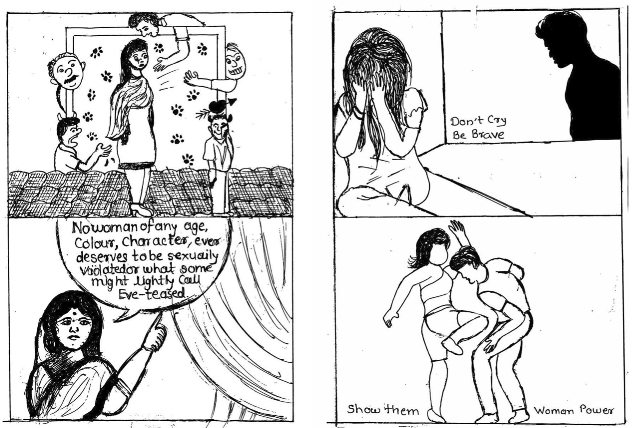

Susie Vickery and Nika Feldman’s Art Box was titled “Provoke/Protect,” in which participants decorated hand-me-down saris with applique designs and stitching responding to the Nirbaya rape and India’s struggle with violence against women. Filmmaker Manish Sharma taught women how to use video cameras, with the purpose of making a movie addressing the menace of public urination and lack of public toilets for women. Writer Prajna Desai, who has contributed reviews of Indian graphic novels to TCJ, organized a workshop exploring how women’s sense of self develops through their personal relationships to food and cooking, resulting in a cookbook titled The Indecisive Chicken: Stories and Recipes from Eight Dharavi Cooks. And, the occasion of the present article, designer, filmmaker, and cartoonist Chaitanya Modak worked with a group of sixty-five, mainly teenagers and young adults, to create short comics about life in Dharavi. These have been collected in Comics Epidemic: An Anthology of Tales From Dharavi. Chaintanya was kind enough to submit to the interview below, where he talks about his career as an artist and activist and his collaboration with SNEHA. There was also a second comics-related project, Ram Devineni’s “Priya’s Shakti,” in which Dharavi residents collaborated in the creation of a comic, murals, posters, and animation around the story of a woman who “takes on the fight against gender-based sexual violence in India with the help of the Goddess Parvati.”

It would be worth writing an essay surveying the many ways comics have been employed in India to social ends. To me, this is one of the most interesting and historically important features of contemporary Indian comics. It is the flipside and wellspring of the heavily touted “rise of the Indian graphic novel,” which has noticeably faltered since its hillock-sized peak of 2007-2012. Between professional graphic novels tackling discrimination and displacement in historical or contemporary perspective, NGO-sponsored anthologies of comics on specific social issues drawn by professional cartoonists, and NGO-organized comics workshops like Comics Epidemic, “social comics” must account for a good fourth of comics production in India.

Granted, one reason the ratio is so high is that the commercial comics industry in India is fairly small. Nonetheless, the volume and variety also testifies to the extensiveness of NGO-related cultural activities in the country, as well as the political and moral orientation of many Indian cartoonists. Many of the top names in graphic novels split their time between market work and activist work. Vishwajyoti Ghosh, for example, author of Delhi Calm (2010) and editor of This Side That Side: Restorying Partition (2013), has spearheaded at least two projects dedicated to social causes: Inverted Commas and the Gurgaon Mapping Project. Navayana in Delhi has published a few graphic novels and comics-like adult storybooks on untouchability and other forms of ingrained social discrimination, like A Gardener in the Wasteland: Jotiba Phule’s Fight For Liberty (2011) and Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability (2011). Orijit Sen, while overseeing People Tree Studio in Delhi and Goa, has been involved in various NGO initiatives around the country. His River of Stories (1994) tackles the displacement of rural communities caused by the construction of the Narmada Dam in Madhya Pradesh. As purportedly the first Indian graphic novel, it practically impressed social engagement on the medium like a birthmark.

Then there is Sharad Sharma’s World Comics India (WCI), the mother of all NGO-based, activist comics initiatives. It is probably the largest such in the world, even without its global extension through the World Comics Network. Since its beginnings in the early 90s, World Comics has comprised over 1000 workshops, involving over 50,000 artist-participants, in countries spanning the globe from Tanzania to Finland, and in almost every state in India. The core concept is simply and effectively called “grassroots comics.” The idea is explained as follows in the informative Grassroots Comics: A Development Communication Tool (2007): “Grassroots comics, i.e. comics that are made by socially active people themselves, rather than by campaign and art professionals, are genuine voices which encourage local debate in the society. Furthermore, they are inexpensive and the technology is not complicated – pens, papers and access to a copying machine are usually enough.”

Usually, World Comics India, wherever it goes, collaborates with local activist groups. A trained “comics tutor” will be sent to conduct a workshop, the composition of which, in terms of age and sex, differing widely according to locale. The tutor first gets workshop participants to speak about social and political issues important to their daily lives. The participants are then instructed in the basics of how to make short four panel comics, from step one of conceiving a story idea, to breaking the story down in panels, and finally inking the drawings. The finished comic is then photocopied and pasted onto walls. Other formats like eight-page booklets are also produced. The range of topics depends on the locality, and the nature of the collaborating NGO: from concerns with water shortages in states like Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, to illegal deforestation in Mizoram. Political corruption, male alcoholism, discrimination against women, and health problems due to bad sanitation have been treated in workshops in many states, giving you a sense of how extensive these problems are in India.

As the Grassroots Comics handbook explains, “What makes these comics different from professional material is the fact that they are made mainly for local distribution. The comics are pasted up in meeting places, bus stops, shops, offices, schools, on notice-boards and electricity poles, etc. The readers usually know the organization which has put up the comics. Proximity is important, the source of the communication as well as the readers are not very far apart.” Because of this intimacy, wall posters and comics have been adapted for publication in local newspapers, which in turn has succeeded in bettering local society in concrete ways. In newspapers, they have convinced local government authorities to better attend to their constituencies by installing, for example, long-promised hand pumps. Pasted on walls, they have facilitated the exchange of advice between farmers about how to better grow and sell their produce.

If grassroots comics have democratized artistic production, it was not mainly so that everyone might enjoy the pleasures of creation. That has been an added benefit, while the primary goal, judging from the organization’s publications, was to improve upon what the NGO world calls “development communication tools.” The contrast between humble grassroots comics and newsstand comics entertainment is, therefore, less relevant than how “user-generated” material potentially improves on the ways the comics medium has been used within social activism. “A usual practice of Delhi-based development agencies,” explains Sharma in a recent article for Marg: A Magazine of the Arts (December 2014), in a special issue on comics, “was to engage artists to develop materials or any new social campaign. The content would be printed on expensive glossy paper in colour, and smaller agencies spread out across the country that could not afford to employ professionals relied on such materials. But India’s culturally and linguistically diverse population was looking for locally relevant content, as that supplied from the capital did not address local problems, and people could not identify with the characters and ambience portrayed in these materials.” Sharma believes his method to be much more effective in addressing “the issues of the silent majority” and effecting change on the ground. I wonder what someone like Vishwajyoti Ghosh, whose activist work has often been the kind of glossy outsider-produced work that Sharma criticizes here, thinks of this assessment.

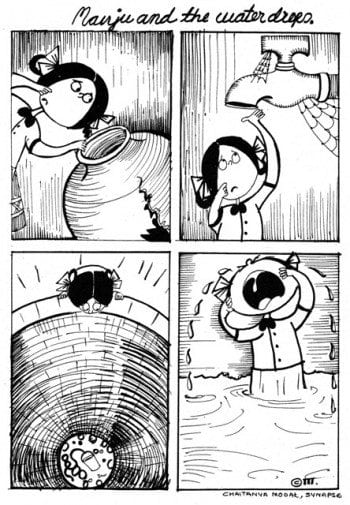

If one wants to get a sense of what Sharma’s organization does, the easiest thing to do is visit the World Comics India website. I had first come across their work years ago, but thought I should re-familiarize myself for the present article, considering that, even though SNEHA and the Dharavi Biennale have no direct connection with WCI, the style and content of Comics Epidemic was clearly in the Sharma vein. So I reached into a musty back corner of my bookcase to fish out one of WCI’s earliest publications, a compilation of grassroots comics from across the country titled Voices from the Field: People’s Comics (2004). After turning through pages of embattled stories in generally wonky draftsmanship, I came to the Maharashtra section (Maharashtra is the massive and largely rural state of which Mumbai is the capital) where there was a four-panel comic of uncharacteristic competence titled “Manju and the Water Drops,” showing a little girl looking disconcertedly into an empty terracotta jug, into an empty well, and at an unused tap, before she breaks into tears. The caption reads: “Conserve water today to avoid getting flooded by tears tomorrow.” It was only on a second pass through the book that I noticed the signature: Chaitanya Modak, the mentor-artist for Comics Epidemic.

Chaitanya’s connection with World Comics India will be addressed in the interview below. As you will see, in his case the grassroots comics model fits into a wider interest in using various media to empower local communities, as much as it does into an interest in comics per se. But before hearing from Chaitanya about this and more, let me provide a capsule review of Comics Epidemic: An Anthology of Tales From Dharavi.

“In the beginning, there was no epidemic of comics,” writes Chaitanya in the book’s introduction. “There was just the simple art of creating a black-and-white narrative out of paper, pencils, and pens.” The result is a collection of forty-three comics by just as many people, split roughly evenly between male and female, ranging in age from thirteen to fifty-six, but mostly young adults in their late teens and early twenties. Subjects cover such issues as nutrition, public safety, mental health, domestic violence, female empowerment, and adolescent sexuality. The vast majority of the comics are in Hindi, peppered with some colorful English phrases. There are a few wordless comics, but most of the contributions are powered by frank and emphatic speech balloons. Length varies from three to sixteen panels. The stories come from the artists’ daily lives in Dharavi. They feel honest, and quite a few are downright raw. Here is a horrifying one in English, Nirant Kondave’s “70%.”

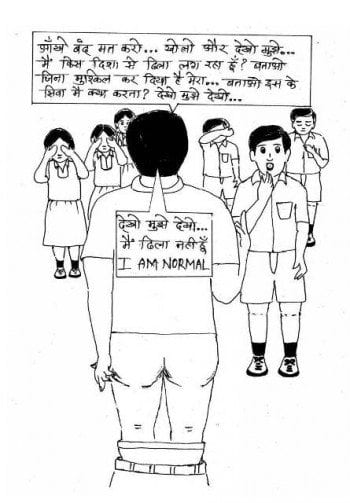

“The comics in this anthology are all made by first-time creators,” explains Chaitanya in the introduction. “They started off by saying, ‘I have never read comics . . .’ To which they have now added, ‘but . . . I can make them.’ Everything is here. Everyone can draw.” That said, the power of the contributions also depends on the reader’s knowledge of context. Many of the comics read like standard adolescent reflections on hanging out, troubles at school, conflicts with family, romantic longing, and sexual desire. One might as well be in the middle-class suburbs.

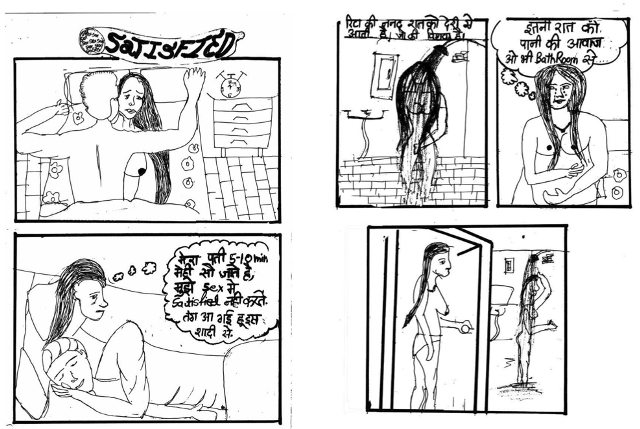

But then, turn the page, and suddenly alcoholism, prostitution, and brutal acts of domestic violence appear to remind the reader that these are episodes from a specific world. Not that these problems don’t exist outside slums. But their frequency and intensity in Comics Epidemic suggests a society in which they are all-too-frequently part of daily life.

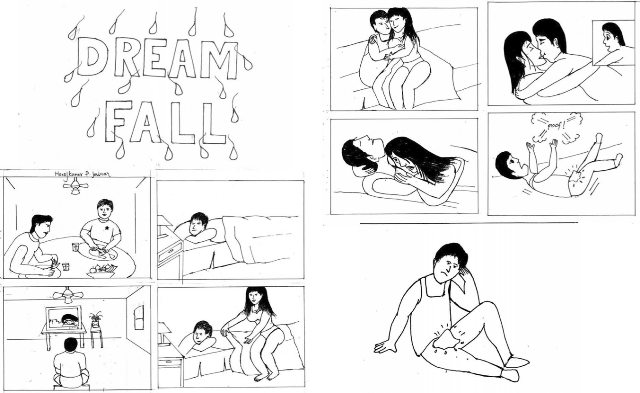

It has been pointed out to me that it is rare to find in India (in print at least) such explicit expressions of sexuality as one sees in Manojkumar Jaiswar’s “Dream Fall” (depicted above) or Rupesh Sable’s “Satisfied.” This might be less an expression of Dharavi per se than the open nature of SNEHA’s Art Boxes, which in many cases addressed sexuality with a directness fairly uncommon in India. Aggressive engagement with female sexuality and empowerment is probably the anthology's most timley contribution.

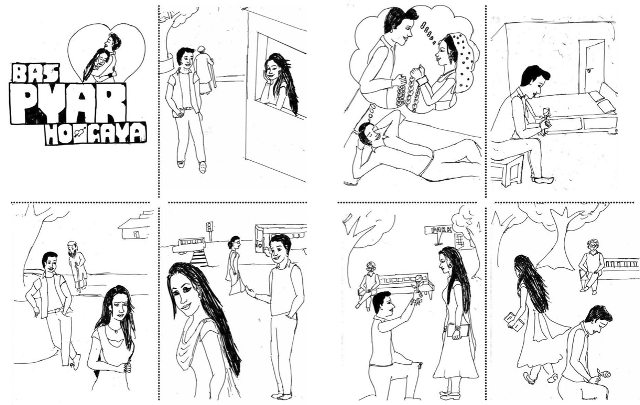

Difference manifests in Comics Epidemic also in less dramatic ways. For example, if you know the dusty and jumbled landscape of Dharavi, it is the verdant park in which two lovers meet in Saraswati Bhandare’s “Bas Pyaar Ho Gaya,” rather than the tears and kisses between them, that appears as the real fantasy element of the story. Or, when a boy dreams of being Superman after watching the hero on television in Raghavendra Pol’s “Pratibimb,” and then climbs to the top of a building and falls to his death, one suspects that suicide is a reality close to the artist’s home. Even pizza parties, which appear in a number of the comics and are not a cheap thing in India, come to have special significance.

Go to a bookstore in Mumbai and you will find many portraits of Dharavi and its people. They usually focus on adults from different regions working in different trades. Yet there is nothing, to my knowledge, on Dharavi’s youth, whose lives in most cases are a far cry from the street urchin image popularized in film. I am in no position to judge Comics Epidemic as a “development communications tool.” But I can say that it has provided me a glimpse into the present-tense of life in Dharavi from a perspective that I have not come across in the standard articles and books. Most valuable, I think, is their frank expression of fantasy. Given how rapidly Dharavi is changing – takeover by developers is constantly in the offing – I suspect Comics Epidemic has captured a transitional moment when the imaginary of “slum-dwelling” has crossed with that of relative affluence and consumer culture. It would be interesting to see how these young artists look back on their work and the world it represents in ten or fifteen years, by which point Dharavi might have ceased being an “informal settlement." The popular "mega-slum" is already misleading.

That, anyway, is my non-specialist outsider reading of Comics Epidemic. I have been to Dharavi no more than a half dozen times, spending no more than a couple of hours wandering around on each excursion, guided intellectually by a handful of articles, a couple of books, and brief chats with the Biennale people.

Better that you learn about Comics Epidemic from the artist that made it happen. So here’s Chaitanya Modak, who not only has years of experience with NGOs, but also a wide-ranging professional practice as a filmmaker, designer, and indie-comics author and publisher.

Can you start by telling me about your background as an artist?

I don’t have a background in art as far as my schooling is concerned. I came into contact with Balbharati textbooks in early school and remember in vivid detail the illustrations by Mario Miranda. He was a big influence later. My mother got a subscription for us to Misha, an illustrated children’s monthly from the USSR. It was full-color and lovely to read. A cousin who collected Garfield, Beetle Bailey and Dennis the Menace in a scrapbook junked them and I inherited them from the heap. The same cousin introduced me to MAD Magazine; it was my first love. Later in school, a friend from my colony introduced me to Target, an illustrated monthly meant for young teenagers. In the 1990s, with the advent of STAR TV, I got to watch Garfield and The Simpsons.

I never really got interested in thinking of art or comics as a profession. You had elementary and intermediate exams in drawing as a matter of course in school. But I chose to do a Bachelors in Commerce, which was the least taxing studying-wise, and got into the Brihan Maharashtra College of Commerce (BMCC), Pune, after first joining their amateur theatre group. Soon I started preparing for my chartered accountancy exams, which I was pursuing more because everyone else was doing it. I wasn't too keen about it myself. I was also toying with the idea of an MBA.

So when did you start drawing?

Things started changing at the start of 1998, when I put up some twenty-odd sketches of animals in the college exhibition. I also used to draw a lot of women from magazines and stuff, but of course, I couldn’t put those up in a college exhibition. The night before the exhibition, a friend helped me paste the sketches inside cardboard frames. Leaving them to dry overnight, I went next morning to collect them. As I saw them scattered across the room in the morning light, a funny idea dawned upon me, “Hey, these are not so bad… maybe I should do something with art.” A few days later, I also won the college ‘Best Personality’ contest and was given the title of Mr. BMCC. Consequently, I received a noticeable mention for my work in a local newspaper.

As luck would have it, one of the judges for the event was Suchairit Rajadhyaksha, a film reviewer for the Times of India. Seeing my sketches, he suggested I meet a sub-editor he knew at the newspaper’s office. At the time, I didn’t even know what “illustration” was, until I saw the word in print!

My first assignment was to illustrate this David-and-Goliath type concept about small mushrooming IT firms fighting the might of large corporations. I cycled to the University of Pune where there is a marble copy of Michelangelo’s David, and I sat and sketched him for a whole day. The sub-editor liked what he saw. Computers were new at that time and for the first time I saw a scanning machine and watched it create a soft copy of my drawing. When the newspaper came out the next day, I paraded it around in front of my family and friends, who were all very impressed.

Then I started freelancing for the Times of India, India Express, Mid-Day, the Marathi-language daily Loksatta in Marathi, and the women’s magazine Chatura.

So you were working full-time as an editorial cartoonist?

I was a freelancer at that point, but there was enough happening every day that I would just hang out at the newspaper office and they would tell me come at a certain time and we will have lots for you to draw. There were features, a women’s section, a kids’ section. I had to do illustrations for all sorts of things. This started in 1998 and continued doing this until about 2002. In that period, I probably drew something like 3500 images. After that, I shipped myself off to Goa and got into corporate communications projects.

Were you paid by the piece?

Yes, at that time, I got one hundred rupees [1.7 USD] per illustration. Other places, like Kishore, a children’s magazine, gave you 25 rupees, 50 rupees, or 75 rupees, depending on how large they printed your illustration. It didn’t matter how large the original drawing was. It depended on if your illustration filled a quarter-page, half-page, or full-page. Covers fetched 400 rupees [7 USD].

How much were you making a day?

Just pocket money actually. But I still felt that maybe if I drew a lot, then eventually it would add up to something.

Did you have any opportunities to do four-panel strips, or other narrative work?

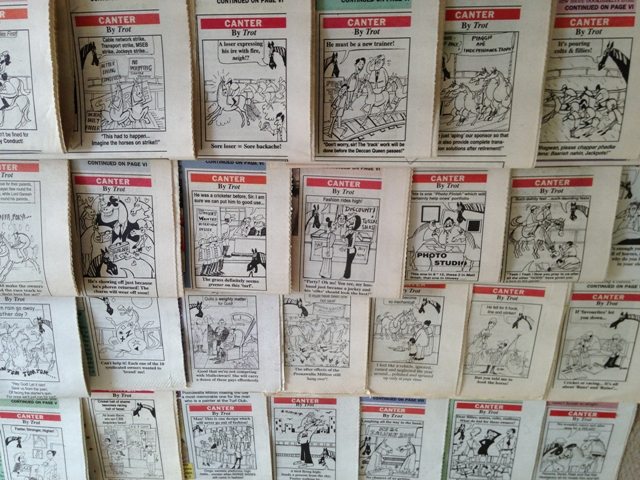

Yes, first for Riding High, a weekly tabloid on horseracing published by the Indian Express Group. It covered the circuits in Mahalaxmi in Mumbai as well as in Pune. I contributed a single panel cartoon slot titled Canter by Trot. It was about a horse named Trot and what he saw around the racecourse. The tabloid’s correspondents and marketing people went around the circuit and reported on what they saw and heard. My job was to come up with a cartoon based on their observations. Say there’s been a rigging or a jockey who has been suspended, they relayed that news to you and you have to figure out what could be done with it.

That kind of reminds me of the early Mutt and Jeff strips, which were often set at the racetrack, with betting tips embedded in the strip. After a while it moved into a continuous narrative and became a family drama.

That’s funny, because punters were always looking for hints, so they thought the tabloid might be hiding clues somewhere. They used to think that maybe the cartoon was pushing for this filly or that jockey, which it wasn’t, but they would really pay attention to anything we said.

After that, what kind of work did you do?

In 1999, after completing my graduation, I joined a famous art college in Pune, because everyone said you should do formal training. But after three months, I quit and joined a publication house in Pune as a layout and design intern. This was run by Nana Joshi, a famous artist and illustrator, who was publishing mainly books on agriculture at the time.

As a child, I remembered my father would cutout and keep paintings by Joshi. I was also exposed to works by other illustrators like Dinanath Dalal, and the cartoonist S.D. Phadnis. While with Joshi, I got to see how they create an issue of a Diwali Ank, a type of yearly magazine published during Diwali, the festival of lights. Typically it carries literary works with naughty double meanings as well as adult humor cartoons. In his later years, Joshi started painting in Photoshop. It was lovely just sitting and watching him work. He used to make these beautiful semi-nude images of women. He worked in a very realistic style.

After six months interning with Joshi, I moved on to Pune Newsline, which belongs to the Indian Express Group as a layout artist. While there, Ram Pandit, a manager in the circulation department and I, struck on an idea for a daily cartoon strip in Loksatta - a sister publication and the then top Marathi newspaper in Maharashtra. The strip was titled Bhopu. Bhopu is a huge and gregarious rickshaw-wallah [a motorized rickshaw driver], and the jokes happened as he rides around town, interacting with his passengers or with the police, or these three school kids he would drop off. The response was great! People really liked the main character, since dealing with rickshaw-wallahs is a common experience.

Were you paid extra for doing the strip?

Yes, but we really had to move heaven and earth. We also owned the copyright.

What happens after this?

I moved to Goa and started doing corporate communications through Synapse. As a graphic designer and illustrator, I did a lot of caricatures for companies like Hewlett Packard. Through some miracle, I even got to spend a half-day with Mario Miranda at his ancestral house in Loutolim!

Then I went off to NID, the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, to do a postgraduate diploma in Film Direction and Visual Communication. Here, I did the first draft of my first comic in an elective class on comics. It was called the Parrot’s Tale. It’s a visual reconstruction of Rabindranath Tagore’s poem, “Tota-Nama.”

While at NID, I was working with an organization in Ahmedabad called Drishti. They had this community radio initiative called “Radio Ujjas” in Kutch, in Gujarat. They trained a group of about sixteen youngsters from all over Kutch to act as radio reporters. They used to include songs, features on local artists, and radio dramas. Their goal was creating media access for people who would normally not have that.

That’s where my interest in that kind of work began. I ended-up making a film about community radio as my diploma project. I spent six months researching the topic, meeting the people involved, interviewing them. The film is called Voices of Kutch (2006). It is a documentary about community radio programming and the universals that come into play, when you want to get communities involved in media. It looks at the whole set of what the organization does, from training people to teaching them interview skills. India has public radio, which is called All India Radio. They should be doing these things. But really only a small section of society is served by it. Hence, people feel the need for their own community station.

Parallel to this, Drishti got involved in the same thing but in video through another organization called Video Volunteers, a New York-based charity, training communities in video. They started working for various NGOs in Ahmedabad, giving people training in video reporting, how to do interviews with simple handheld cameras, filming techniques, post-production, scripting for a documentary. So I gained exposure on how communities can use media such as radio and video to get their voices heard. My intention was to understand how do you get people into media, what are the specifics of that media that people have to be trained to understand, and then how to hand it over to them, so that they can claim it for themselves.

At what point did this interest in social communications cross over into comics for you?

For me, the interest in all of this was less in comics per se than the empowering of communities through media, whether that was radio, video, or comics. I was also experimenting with what happens to a content idea when the medium changes from print to audio/visual. For example, in 2003, I made a comic for World Comics India, run by Sharad Sharma at a workshop in Bangalore. The comic, “Manju and the Water Drops,” is devised as a subconscious reminder of how we take our natural resources for granted. Very simply, it is a girl crying over lack of water. Later, it served as a storyboard for a film I made at NID called Sparrow’s Tears (2004). You can view it online. It won a silver in the public service campaign category for the Indian Documentary Producers Association.

I found the workshop and its idea that anyone has the ability to draw to be very enlightening. Since I am a self-taught artist, I found that to have a lot of resonance. I think art schools and art teachers make too much hue and cry over something that is really a simple matter of seeing. The grassroots comics concept was a great antidote to this.

The style of “Manju and the Water Drops,” the comic, reminds me a bit of Mario Miranda, who you said you were a fan of.

Yes, that comic does have the sense of expression which Mario’s characters embody. The comic works because it is wordless and speechless.

How did you get involved in comics mentorship programs?

Teaching is a great form of learning. All the queries you have for yourself resonate with the people you are teaching. I started by conducting small summer workshops for a Mumbai based organization called the Pomegranate workshop. Also, Sharad Sharma had referred me to the Aliyavar Jung National Institute of Hearing Handicapped, (AYJNIHH) which is in Bandra Reclamation in Mumbai. I worked as a visiting faculty there, conducting sessions about understanding comics, how to use comics to understand disabilities, and also how to use comics to help disabled people communicate.

Tell me about the new project, Comics Epidemic.

Since 2011, I had been working with SNEHA on their communication collaterals. This included designing the report for Dekha Undekha (Seen Unseen), the prototype of the recent Dharavi Biennale. That was in 2013. When I saw all the images of the exhibition and the local people who had attended it, I thought it would be interesting to propose a comics project with them. So I got really interested in what an Art Box, as they called a workshop, is, how it functions, and what it might be capable of. After my proposal was accepted, we did four Art Boxes over the past two years. And eventually this became Comics Epidemic.

Can you describe Comics Epidemic for me?

SNEHA’s Dharavi Biennale is an art, health and recycling project. We were trying to understand what are the connections between the people who live in Dharavi and the kind of things they experience on a daily basis, from the moment they get up to when they go to bed, what do they encounter. We had four specific themes, which we explored through separate Art Boxes. These were Food and Nutrition, How Safe is Your World (where we looked at road accidents, animal –human conflicts, street fights and so on) and sexuality and relationships. There was also one about gender based violence we did for "Priya’s Shakti." We were looking at emotional health as well as physical health. The name, Comics Epidemic, was meant to express the idea that maybe comics will catch on and spread like a virus, while also dealing with health issues.

How many people participated?

We had a total of about sixty-five participants. There were seventy-six comics produced, from which we chose forty-three to be included in the anthology. The boy to girl ratio was about even. In terms of age, I specified that I wished them to be at least twelve. The youngest participant was thirteen, I think.

The participants I saw at the opening were all in their high teens or early twenties.

Yes, that’s right. But in the workshop, we had elderly people as well. One person was fifty-six. There was no upper age limit, only a lower age limit.

In general, how did the boys’ comics differ from the girls’ comics?

I wouldn’t claim that there was too much difference in thinking about comics between the male and female participants. Except for comics on sexuality and relationships. Here, the guys made comics that were more “revealing” on the topic. For the girls, if they made comics on sexuality and put it out in public, people assume they are “like that.” There’s also the fear of your parents or a family member seeing it.

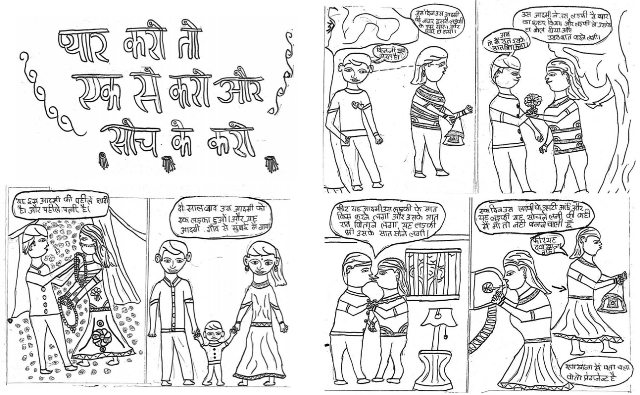

But there was one 14 year old girl who broke these rules. Her name is Gudiya Pande and she did a very beautiful work called “Pyar Karo toh ek se karo, Aur soch ke karo” (If you fall in love, let it be long-lasting and well thought out) It’s about a guy whose married in his home village, but then he comes to the city and gets involved with another woman, who he leaves once she gets pregnant. That's the story; I really wondered how she came up with it at her age. She did a fantastic job with the illustration and capturing people’s expressions.

I heard that you had one case in which a girl got in trouble for her work.

She had done a comic about a local gangster in her area who would hit his wife and visit prostitutes. This comic got featured in a Mumbai tabloid while the workshops were going on, along with her name and a description of the piece. Apparently a friend of her brother saw the article, but didn’t understand English very well. So he mistook her to be featured as a prostitute. When the participant’s brother heard the gossip, he slapped her badly. But the girl came in the next day to the workshop very cool about the whole thing, saying, “He slapped me once or twice, but whatever no big deal.” And we had just been talking about doing comics treating domestic violence, and here you had a case of comics creating domestic violence!

In Comics Epidemic, there are a number of comics about pizza, strangely enough. Why is that?

We were under the impression that kids would become health-conscious if they made comics on nutrition. Funnily, they went in a completely opposite direction, narrating their own experiences. Instead of showing how junk food was unhealthy, they depicted their group outings for a “pizza party.” The thing is that pizza outlets won’t deliver to Dharavi; pizza companies think Dharavi is unsafe or socially backwards, a problem area. But, for the kids, pizza is an aspirational thing. Dharavi is like any other community in many ways. The public facilities might be horrible, but people do work hard and have money, so it’s not like pizza is beyond their means.

Describe what happened in a typical workshop, from the first session to the finishing of a comic.

Broadly there were two sections. First you deal with the subject matter, through experts, books, films, or any other available media. The experts could be counselors from SNEHA, doctors from the hospitals, or health experts. You have to learn the content quickly, have a quick but well-rounded understanding of the subject matter so that you can do a comic that is informed. After they chose the subject they wish to explore, they talk about their own experiences or stories they have heard from other people. And from there they craft their own stories for the comic. It’s like a fast pill.

Parallel to this is developing the observation, drawing skills and the visual grammar required for handling of the comics form. Most people think, when it comes to drawing, that either you are naturally good at it or you cannot do it at all. Nothing in between. The philosophy of Comics Epidemic is that everyone can draw, that everyone has their own style. This creates a space for people to think of their drawing, however it looks, as a kind of expression, rather than reducing everything to degrees of artistic excellence. Expression was the important thing, especially self-expression, capturing your own story.

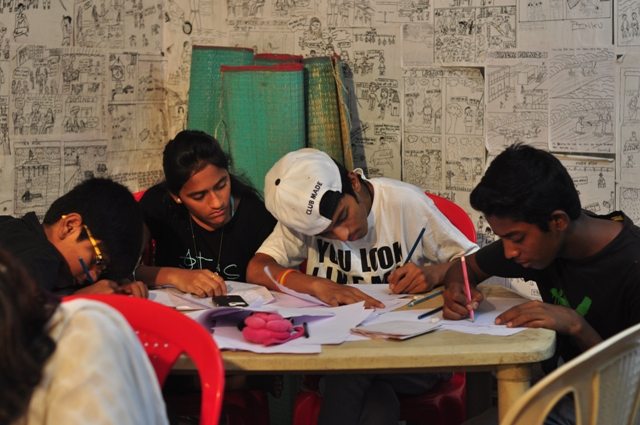

The best thing about these workshops was that anything you do, it happens within a community. Normally one thinks of drawing, writing or any creative endeavour as a solitary activity. At these workshops, however, everyone sits together at a table, they are making fun of one another, pulling pranks on one another, playing loud music from their phones, and constantly talking. A lot of them were helping one another also. In that sense, they learned how to “outsource,” getting someone else to do the drawing for them. But we put a stop to that very quickly!

What was the most difficult thing for the participants?

The most important thing is patience. It’s not about taking more time with the drawing, but just sitting for five minutes to think about how to do it.

Had any of them read comics previously?

No, that was the craziest thing. I brought in a lot of popular Indian comics like Chacha Chaudhary, Tinkle, Amar Chitra Katha, thinking that maybe they wouldn’t all be into Marvel, DC, or Vertigo. But none of them had seen any of it. Their visual imagination was mainly coming from the movies, but what we really wanted to get out of them was their personal visual memories.

After they create the comics, then what happens?

Then they put them up! We pasted them on public walls, outside public toilets, outside shops, outside someone’s house. This was a nice way to get immediate audience reaction. It’s not like when you publish something and someone might review it later. It’s immediate. The moment the participants see their comic in public and people looking it, they become artists…like an artist in a gallery, only their gallery is the road.

What kind of public responses did you get?

Again, even with the public, no one had read comics. A lot of people didn’t understand how to read the comic. Whether you start top to bottom, whether you should go left to right, or right to left. Kahan se shuru karoon? Where do you start, they would often ask? The artists didn’t read comics, the public didn’t read comics, so you got this challenging interaction.

Finishing up, tell me about your own professional practice.

Since 2010, I have been living in Bandra, where I have a branding and design label called Inhouse Design. Over the past four years, I have worked on a diverse range of projects: branding (for restaurants, retail, apparel), interfaces (mobile/touchscreen devices/ web applications), layout and print design (magazines, newsletters, annual reports), as well as illustrations (my first love).

For comics, I have Won-Tolla, which is a moniker for myself, but also the name of my own publishing outfit. Won-Tolla first appeared as a wolf in Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book. Wolves are pack animals, but Won-Tolla is an outlier. He doesn’t hunt with the pack, he fends for himself and his family. As a publisher, I am looking for stories that are true to themselves. Not that they have to rebel against anything, but like Comics Epidemic, they need to be true to the place and to the individual who made them. That’s one working philosophy. The comics also have to be well researched. Most of my titles are based on urban experiences. In terms of audience, they are targeted at a mature audience, but of any age, even if they are children. Best if they have a dash of wit, wry humor, slices of life, and stunning visual spreads.

What is your personal favorite?

They are all very dear to me. They come from personal experiences. Et Tu Brut (2012) is one of my favorites. It was first published in Comix India, but a revised version is now available as its own booklet from Won-Tolla. It’s the story of a dog that wants to befriend a man, but the man doesn’t really like the dog. He likes animals and is sympathetic towards living creatures, but he doesn’t like this particular dog. But the dog really wants to stay with him and become part of his family. Unfortunately his friendly overtures are repeatedly ignored. Honestly, I lived with a dog like that for some time.

The Oracle of Tripe (2013) was the first collaborative comic I had done. It was with Benita Fernando, a Mumbai-based writer and journalist. We were looking at ideas of non-violence, vegetarianism, non-vegetarianism, which then morphed into this story about fate and human destiny. What was nice was that I got to read a lot for that project from the Rig-Veda about sacrifices and texts like the manusmriti about the caste system. The comic tells the story of a man who wants to know when he’s going to die. He meets The Oracle of Tripe, and she tells him when he’s going to die. He wants to escape this fate, but doesn’t know how.

How do you sell these comics?

They have been available in stores, like in Kitab Khana in south Mumbai, and Either/Or and Loose Ends in Bandra. But sadly many of the stores that carried them have shut down. They are available now on Amazon. I have also sold them at the Mumbai Comic-Con and The Hive community market in Bandra. Comics Epidemic will also be available on Amazon, and also on the Won-Tolla site.

What comics projects are you working on now, or have planned for the near future?

Since Comics Epidemic, I have gotten interested in the idea of an anthology. I have been considering different scripts, but a lot of them are mythological - superhero things, which I want to steer away from. I am looking for more realistic stories, and maybe do an anthology through Won-Tolla. Everyone wants to get into comics, and right now my main concern is creating a platform to help comic creators get material out into the world.