A cursory scan of comic book history reveals case after case of creators getting screwed by editors, publishers, and distributors. From Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s exploitation by National Periodical (DC) to publisher Victor Fox’s non-payment of artists and writers to the travails of Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and others at 1960s Marvel Comics (to name some of the more prominent episodes), the industry has been brutal to its creators.

For each of these well-known events, there are hundreds of unknown sob stories. Creators routinely signed away the rights to their original concepts, had their work butchered by heavy-handed editors, and suffered as the comics industry weathered financial upheavals.

That’s comic books. Newspaper comics are another thing. Until newspapers began to wither in the late 1990s, a syndicated comic strip was a cushy gig. Unless a creator consistently blew deadlines, fussed about the syndicate’s treatment of their work or otherwise made waves, a strip represented a secure income—for established and successful creators.

Strips could be cancelled, due to a lack of subscribing newspapers, or given to new creators—they were largely owned by the syndicates, as comic book features were by their publishers. Comic strip artists were more respectable—Charles Schulz, Al Capp, and Milton Caniff were celebrities in their heyday, while ________________ (place your favorite comic book creator here) seldom got positive media coverage—if any at all.

In mid-20th century America, any syndicated comic strip had a receptive audience. There might be more call for Dick Tracy, Li'l Abner, and Blondie than for Priscilla's Pop, Boots and her Buddies, or Jeff Cobb, but any feature had a fighting chance. No matter how good or bad a strip was, it had the potential for some degree of success. A popular strip was circulation-building for competitive papers. Despite decreased page space in the post-war period, comics still had clout.

Vic Flint was typical of the unpretentious, reliable narrative comic strips that filled the pages of post-War papers. It debuted on January 6th, 1946 as a daily and Sunday series. The strip was part of Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA)’s package of features. NEA, like the Associated Press, was a service rather than a syndicate. They offered small-town dailies and urban evening papers access to a full package of comics, columns, and other features. For a flat fee, subscribing papers could use as much—or as little—as they wanted. Due to the service’s appeal to small-town newspapers (and urban evening dailies) across America, NEA strips were ubiquitous.

NEA’s roster of strips held to a fixed number until the later 1960s. If NEA wanted to launch a new comic feature in the 1940s or ‘50s, they had to kill one of their existing strips. They seem to have ignored that rule when they introduced Flint to their line-up.

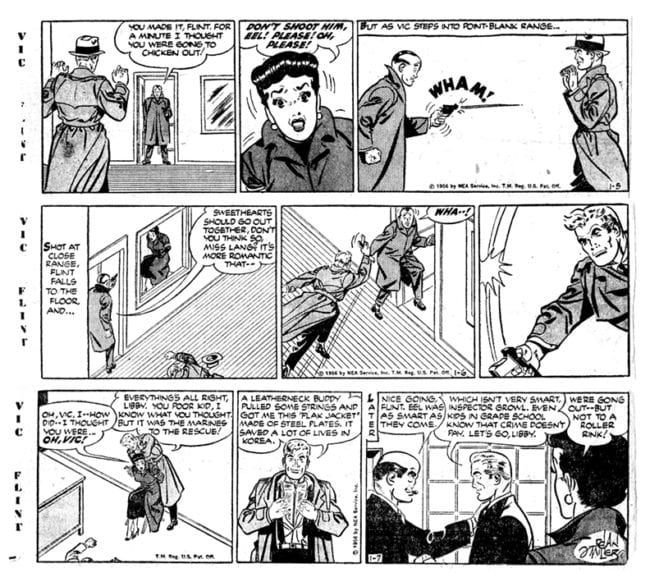

Vic Flint was scripted by Ernest Lynn (as "Michael O'Malley") and drawn by Ralph Lane, Roy Crane’s first assistant on Buz Sawyer. It was clearly devised to horn in on Dick Tracy and Kerry Drake’s territory, but with a new wrinkle for comics. Flint was a private eye—chain-smoking, world-weary, and the narrator of his own adventures. Comics had plenty of G-men and police detectives, but this tough-talking gumshoe was a newspaper first. Flint was a precursor to Blake Edwards's TV P.I., Peter Gunn: he had a love-hate relationship with a police inspector and, especially in the 1950s episodes, a certain cool and style.

Lane’s artwork on the strip’s first four years is attractive, clean-lined cartooning that sometimes shows a hint of his former boss’s influence. Lane left the strip, in mid-storyline, in 1950. Why he left the strip remains unclear. He continued to work for NEA, doing short-run topical or seasonal comic

strips and feature artwork, according to a career profile posted on Allan Holtz’ Stripper’s Guide blog in 2017.

Lane’s replacement was Dean Miller, an ambitious young cartoonist who took over George Merkel’s strip, Mighty O’Malley, Ex-Marine, for the Chicago Tribune’s syndicate in 1948. The Trib apparently chose to run the strip only in their higher-priced edition for out-of-town subscribers. The one existing example in the files of Cheryl Moore, Dean Miller’s daughter, is in a tabloid format—not the Tribune’s typical style—and has, on its reverse, generic filler articles. Allan Holtz did a piece on this mystery episode for his Stripper’s Guide blog.

Born in 1924 in Springfield, Missouri, Dean Miller was an eager artist from early childhood. His cartooning career began at age 16 in the Houston, Texas area where he grew up. World War II interrupted his comics work; he spent four years in the Air Force, where he was stationed in Fort Myers and Miami, Florida. He was a gunnery instructor and taught aboard a B-52 bomber. There, he developed a love for boxing.

After WWII, Miller moved to Chicago, where he found work grinding prescription lenses for eye-glasses—a trade he learned from his father, who was an ophthalmologist. Around this time, he also considered a career as a minister. These work options were dropped when he was hired by the Chicago Tribune to continue Merkel’s strip.

After WWII, Miller moved to Chicago, where he found work grinding prescription lenses for eye-glasses—a trade he learned from his father, who was an ophthalmologist. Around this time, he also considered a career as a minister. These work options were dropped when he was hired by the Chicago Tribune to continue Merkel’s strip.

At age 24, Miller was perhaps the youngest syndicated cartoonist in America. A photograph taken at the Trib’s 1948 Christmas party shows Miller beaming with youthful confidence, his slight frame dwarfed in a big-shouldered, double-breasted suit coat. He points backward to a Christmas tree decorated with original drawings by the Tribune cartoonists. A Chester Gould drawing of Dick Tracy hangs over Miller’s head.

Though Mighty O’Malley never became a major strip (a fate shared by other intriguing minor Tribune features of the era), it caught the eye of Ernest Lynn at NEA. After the strip’s 1949 demise, Dean Miller moved to Cleveland to work for NEA as staff artist. Thus, he was handy when Lane left Vic Flint. Lane’s last daily strip appeared on July 29, 1950; his final Sunday ran on October 8th. Miller first signed the daily on October 7th, over two months after he began his run. His first signed Sunday was the second he did, on October 22nd.

By this time, Flint was written by Jay Heavilin (rhymes with javelin), a former police reporter who wrote whatever needed writing for NEA—columns, boiler-plate promo copy, and other comic strips. Heavilin brought a blunter, darker vision to Vic Flint—ideal for Miller’s bolder cartooning style.

Cheryl Moore retains two Ralph Lane originals sent by Ernest Lynn, with scrawled pencil instructions to emulate the look and feel of Lane’s work. Miller did a commendable job of simulating Lane’s style, which had gone from delicate pen lines to bold brush strokes by 1950.

Within a year, Miller developed a more crisp, concise look for the strip—a bridge between the Milton Caniff school of cartooning (a defining look for 1940s and ‘50s adventure comics art) and the diagrammatic look of his former syndicate-mate Chester Gould. Ralph Lane’s Vic looked like a college boy on a sleuthing lark. Miller’s Flint was more modern and hard-edged. If Heavilin’s narratives tended toward the formulaic, they delivered the goods. Flint’s villains often bore resemblance to Chester Gould’s grotesque baddies—but less so than Alfred Andriola’s Kerry Drake, which shamelessly mimicked the Dick Tracy rogues’ gallery.

Thanks to NEA’s network of subscribers, Miller’s work had a wide, captive audience. An early 1950s advertisement in the Zanesville, Ohio Times-Signal claimed that the strip ran in “more than 650 newspapers.” With a weekly salary of $375 ($3500 in 2018 dollars), the young cartoonist seemed set on the path to professional success. He didn’t own any part of Vic Flint; he was work-for-hire. And though he signed his work, most newspapers credited the strip to Heavilin, or never bothered to change the original O’Malley/Lane byline.

Through December 1955, Miller lived in the Cleveland metro area, and went into NEA’s offices to do his cartooning work. He was in daily contact with NEA’s head comics honcho, Ernest “East” Lynn, whose hands-on approach didn’t sit well with Miller.

“My father didn’t like Ernest Lynn that much,” recalls Cheryl Moore. “I never heard him say anything good about him.” Miller’s decision to move to Fort Lauderdale, Florida at the end of 1955 seemed to cause serious enmity between the cartoonist and his employer. “When we left the Cleveland area in 1955, my father never saw Lynn again. I really don’t think that Lynn liked that my father was mailing his work in and wasn’t coming into the NEA offices anymore. He liked everyone to be where he could scrutinize them.”

Surviving correspondence between Lynn and another NEA cartoonist, Kreigh Collins, who did the successful Kevin the Bold Sunday feature, bears Cheryl’s comments out. In a typical letter, Lynn shifts from a tone of breezy micro-management to making jokes at his own expense about his nit-picking.

Miller’s decision to move from Cleveland and work in Florida wasn’t radical. At least three NEA cartoonists lived and worked in central and southern Florida: V. T. Hamlin, the creator of Alley Oop; Leslie Turner (who continued Roy Crane’s Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy); and Wilson Scruggs, artist of NEA’s soap-opera strip The Story of Martha Wayne. Kreigh Collins lived and worked in the Grand Rapids, Michigan area—closer, but not Cleveland.

As Miller moved his family to Fort Lauderdale, NEA cancelled the daily Vic Flint. Its final episode ran on Saturday, January 7, 1956.

This wasn’t a deliberately malicious act towards Miller. It was strictly business, cold and impersonal. NEA wanted to introduce a new humor strip. Just as Mort Walker transitioned from slick-magazine gag cartoonist to top syndicate earner with Beetle Bailey, NEA hoped that another hot artist, Dick Cavalli, would make a similar impact on the comics pages.

As an instructor for the Famous Artists School cartooning correspondence course, Cavalli was something of a comics celebrity. His Morty Meekle, later called Winthrop, ran until 1994, but never came close to the popularity of Beetle Bailey, Hi and Lois, or other humor strips.

If thought of at all today, Morty is known due to cartoonist Bill Griffith’s satirical and absurd references in his daily Zippy the Pinhead comic-strip. “Morty had absolutely no impact on American society,” the cartoonist’s alter-ego Griffy states in an August 1987 daily.

Meekle’s biggest impact was on Dean Miller. Vic Flint was now Sunday-only.

His $375 salary shrank to $90 (roughly $800 in 2018 dollars). A bachelor on a budget could have hacked it, but Miller was a family man with a mortgage. Recalls Cheryl Moore: “We had a new home in Ft. Lauderdale, and my father had me and my brother [Dean Jr.] and my mother. My mother didn’t work.” Miller found other sources of income—he taught cartooning, watercolor technique and life drawing, did odd jobs of commercial art, including logo design and work for a Miami-based museum of medieval art and relics.

The Miller clan moved to Kansas City, Missouri in May 1959. Miller’s son remained in Florida, where he would soon join the Navy. Miller continued teaching art and mailing in the Sunday-only Vic Flint. By this time, Cheryl became the strip’s occasional colorist. Using a printer’s color chart as a guide, she would watercolor a proof copy and then color-code it with the guide’s numbers. Miller otherwise did everything on the strip.

Though the storylines of the later Flint are so-so, despite the potential appeal of its noir-ish plots and incidents, Miller’s concise, expressive artwork, which chooses aerial points of view, stark diagonals, stylized backgrounds, and a tendency towards caricature, betrays no signs of the artist phoning it in.

Miller’s skills might have been better-served on an original strip. According to Cheryl Moore, he submitted at least two humor concepts to “East” Lynn—one called Tumbleweed, in anticipation of T. K. Ryan’s similarly-named strip. NEA passed on these ideas.

Miller kept busy, with the meager income from Flint still an anchor for his family. In the fall of 1961, as Cheryl recalls, “he got a ‘Dear John’ letter from NEA saying that Art Sansom was taking over Vic Flint. They didn’t call him; they just sent him a letter When that happened, my father was quite devastated. I think I took it worse than he did. I swore I’d never read another comic, and I haven’t since 1961. I was that upset.”

Dean Miller’s last published comic strip ran on January 21, 1962. Sansom, a longtime NEA staffer who illustrated the syndicate’s SF strip Chris Welkin, Planeteer and would create the runaway hit The Born Loser in 1965, added Flint to his workload for about two years. The son of the original artist, John Lane, took over the strip in 1964. His rough-hewn, caricatural style saw Vic Flint to the end of its days. It changed title to The Good Guys in 1965 and was retired in 1967.

By this time, Miller was deep into a new career in the field of animation. He first worked for the Calvin Company, a major producer of industrial and educational films in post-War America. When they cut back their staff in the later 1960s, Miller landed with Bay State Films in Agawam, Massachusetts. There, he worked on classified films for the military, including work for the Atomic Energy Commission. “He used to take train trips to the naval bases in California,” Cheryl Moore recalls. “He did the animation for a lot of training films. He wasn’t allowed to talk about it.”

Was this a good move for Dean Miller? “My father was paid well doing animation and was very comfortable,” recalls Cheryl Moore. Miller invested in real estate and found another revenue stream in rental properties, which he managed to the end of his life. At age 52, Miller took a trip to Hollywood, where he sought work at the Hanna-Barbera TV animation studios. He was offered a job but didn’t live to take it.

On New Year’s Day 1977, Dean Miller died of a coronary occlusion. Clogged arteries were the culprit. Like many men of his generation, Miller was also a chain-smoker. “I never saw my father without a cigarette.”

Dean Miller lived large and enjoyed life. He painted watercolors, did wood sculpture, built model ships, and collected coins and stamps. He enjoyed traveling and, along the way, learned to roll with life’s punches. Had NEA treated him like an asset, and not a disposable cog, he might have stayed in the comics field and developed an original feature. Getting dumped from a decade-long comics gig may have been an initial blow, but it’s doubtful that Miller looked back in anger or regret from his better-paid, more respectable animation career.

Is there a moral to this story? It demonstrates that cartooning is, and has always been, a potentially perilous career choice in America. As with the other lively arts, there is little room at the top. To get (and remain) there requires talent, intelligence and a stiff upper lip.

At this moment, millennial Dean Millers are at work in animation, cartooning, advertising and other forms of mass media. Their gigs are shaky by nature; they knew that when they walked in the door. Job security is a quaint notion of the 20th century; it wasn’t perfect at its best.

Nothing lasts forever. Perhaps the takeaway here is how to deal with the potential of failure: to learn to be flexible and to remain open to new avenues.

Thanks to Cheryl Moore for her interview and for supplying rare photos.