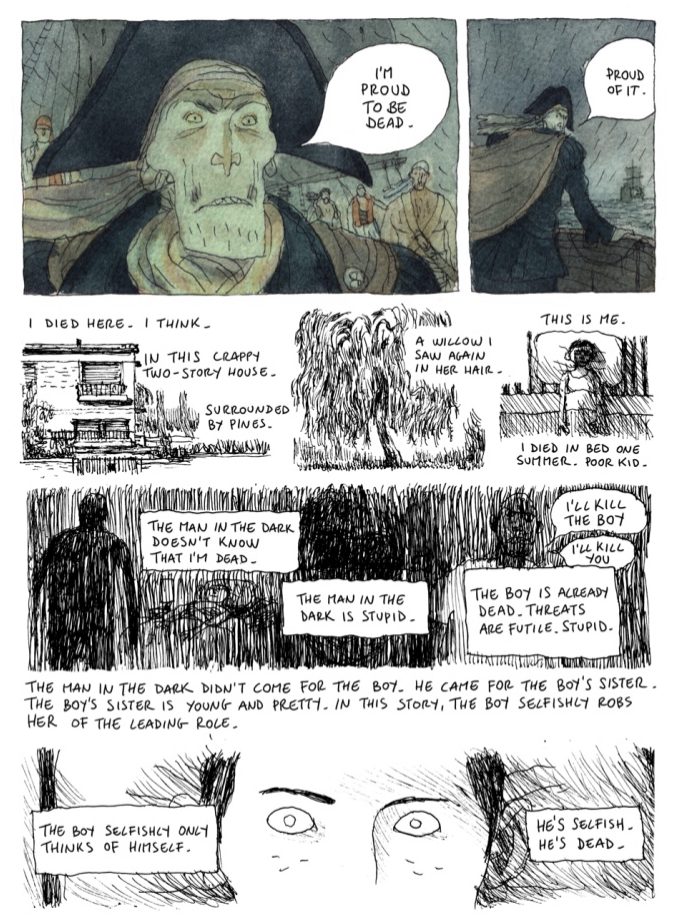

Gipi’s My Badly Drawn Life was originally published by Coconino Press in Italy in 2008, and at the time it had a huge impact both on the Italian comics scene and on Gipi’s career.

Already considered one of the most influential talents in both Italy and Europe as a whole, Gipi made a significant statement with this book: this is my life, I am not afraid to show myself, naked as I am. It was not the first time Gipi had filled a book with his own experiences, but this time there was something different. MBDL came right after S. (Coconino Press, 2006; still unavailable in English), a graphic novel full of memories and emotions, inspired by the death of his father. Yet, in MBDL there was no filter between the artist and the reader. This was not Gipi’s usual passionate fiction; this book was the kind of memoir that the Italian reader was not accustomed to. It was the first time such a direct approach was seen on the page since the 1970s, when Andrea Pazienza penned his improvised and caustic underground comics. In MBDL Gipi shows his anxieties, his health problems, his frustrations, while telling stories from his youth that often lead him to find the reasons behind those issues that afflicted him at the time he was working on the book

MBDL was a great success. It sold tens of thousands of copies—more than any other graphic novel could sell at the time in Italy—and exposed Gipi to the interest of the world of entertainment, opening him the doors of TV shows, with interviews and collaborations.

Now that the book is finally available in English (published by Fantagraphics, translated by Jamie Richards), I spoke with Gianni Gipi Pacinotti to look back at the time he worked on MBDF and see what has changed in him after all these years. The interview was conducted in Italian, via Zoom; the English translation is my own.

-Valerio Stivé

* * *

VALERIO: It’s been almost 15 years since My Badly Drawn Life was first published in Italy. The book was crucial for your career and can be considered a turning point for the Italian comics scene...

GIPI: It feels so weird to talk about that book now, after almost 15 years. The book feels so old to me, and holy shit, it makes me feel so old.

How was MBDL born? What were you doing at the time? Where were you?

How was MBDL born? What were you doing at the time? Where were you?

I was living in Paris at the time. It was a good time for my career. I had moved to Paris after winning the award at [the] festival in Angoulême [Notes for a War Story won the Prize for Best Album in 2006], and I was treated like a prince in the comics scene, but as far as I remember, I was never completely satisfied with what I was doing, because I had the feeling there was a discrepancy between the stories I was doing and the person I was in real life. I’ll try to explain--

My stories were bleak, and some were tragic, but all of them were bleak, and sad. Yet I assure you I am a total jerk in real life. I mean, I love fooling around, making jokes, hanging with my friends just being stupid. But I was not able to put this vitality in my books. I remember how frustrating it was. It was as if when I started working on a book, a dark part of myself ended up getting the best of me.

Thinking about it right now in retrospect I think it was probably all about technical reasons. Dealing with comedy is much more difficult than dealing with drama, at least to me. However, I had this urge to show with my art what I was and what I am in real life. Besides, I was longing for my old friends so much. I was longing for them and for the life I had when I was younger.

One last thing. At the time, I was also feeling responsible for a lot of sentimental train wrecks. So, I started asking myself why. But I’m not that good at looking inside myself, concentrating and actually thinking about my issues. I can’t get anywhere, and I had learned that if something’s nagging me I need to put it in a story to really understand it. So, I said to myself just try and draw a funny story, if you’re actually able to do that, and ask yourself why at over 40 years old you haven’t built anything in your personal life and you’ve left a graveyard of failed love stories behind your back.

In a way, the book was the product of a mid-life crisis.

I can have crises at basically all ages, and they can be equally ridiculous in retrospect and tragic while I live them. Yes, I wasn’t a kid anymore, I had a girlfriend, she was much younger than me; that was leading me to all kind of questions, and most importantly there were times when I was feeling deeply sad.

I still feel that way, sometimes, but at the time I wasn’t aware that those moments were playing a huge role in my existence, and they still do. I do not call them by a medical term because I’ve never used any medication for them, I just call it melancholy. And this melancholy as well was in striking contrast with how I love to laugh and joke with my friends.

I think I understand those books—and I mean S. as well, which was about the death of your father—much better now that I am 40 and I’ve lost a few loved ones.

Sure. If there’s one thing I don’t complain about myself—and I promise you there are plenty—is that I’ve never tried to be something different than what I am. I’ve never sat at the table saying this time I’ll work on this or that kind of story, for this or that specific readership. I’ve always worked on what I actually felt I needed to address, on the specific issues I was actually struggling against.

MBDL is the book of a 40-year old man who speaks about being 40 years old, and also about being young, but from the perspective of someone who isn’t young anymore. So, I understand that it can resonate much less to someone younger. And S. as well. If you haven’t smashed your face against it, you probably won’t even understand why someone has the need to do a book about what S. is about. Why the fuck would you write a book about your father who isn’t there anymore? Because you fucking have to.

He is inside everything I’ve done since that day.

You just mentioned those times of melancholy and the unwillingness to give them a medical definition... that reminds me of all the doctors you visit in MBDL. I couldn’t help but wonder if all of them were real or if your doctor was the book itself?

They were all real. And I know it sounds weird but, exception made for some tiny details I created for the sake of a few gags, almost everything you see in the book was real.

I had the impression your therapy was the book itself.

Art has always been my therapy. Always. I’ve met doctors who deal with the brain, but all the time it feels so weird to be aware that there is something in me that they cannot grasp, you know? I remember one of them who once told me I was deep in the shit, pardon my French, that I was a suicide risk. Yet there was one thing he didn’t know. As soon as I was home, I could translate that shit [into] stories and music. Yes, music is my other passion. I love writing stupid songs that make me laugh, song that luckily nobody else has the chance to listen. [During our Zoom call, behind his back in the studio, I could see keyboards, synths and a guitar.] I’ve always translated all my miseries in art, and I think I’ve been able to do that because those miseries were ridiculous. Because when miseries are serious it’s a whole different kind of shit.

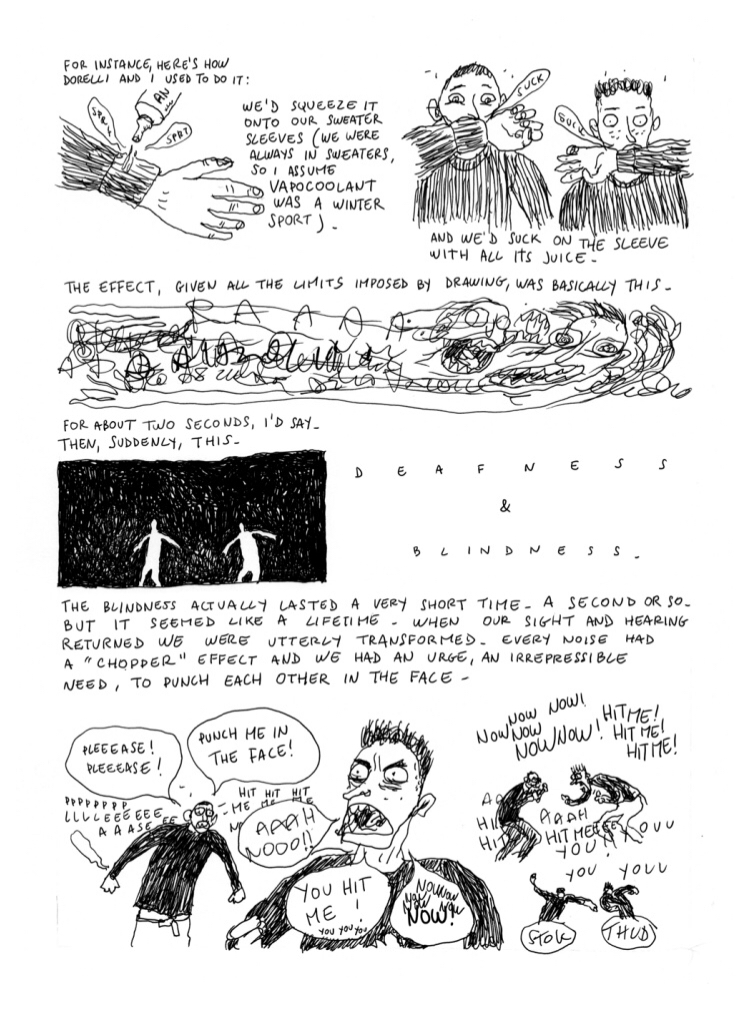

Yeah, I must say that another reason behind MBDL is that once I looked back at my life I realized how incredibly ridiculous it has always been, even in the most tragic moments. Some readers wrote me to telling me whoa, in MBDL there are some seriously tragic moments. While to me nothing there is tragic at all. Actually, there is only one tragic event, and I mean when my sister was sexually abused. That one only. Everything else is just comedy.

The book is actually all about teenagers doing what teenagers do.

Exactly. It was fueled by nostalgia for the time I spent with my friends, living in total freedom, even risking our lives in more than one occasion. But the air I breathed was blessed, there was something amazing in it that won’t be here anymore. But I will never forget it. It was a time of great energy that won’t come back anymore.

At the time, during the '80s, how was Pisa, the city where you grew up?

I don’t know, actually. In my books you can see the places where I grew up, because for many years I gave myself this one rule: only speak about the things you actually know. So, I couldn’t set a story in a place I had never seen before in real life. Now I’m older and things have changed. I’m working on a western story and a sci-fi story.

In the French edition of Notes for a War Story I asked for every place name to be changed with names of actual places in France. My intention was not to tell a story about my places, I was just trying to be true to myself. When the book was published in the U.S., some kids wrote me telling me wow, this is really my hometown. It was great. It was the most amazing thing one could tell me. I’ve never even been in America.

But the real Pisa, the one from the '80s, I have no idea how it was. For one simple reason: the only thing I was interested [in] at the time was drugs. And the Pisa I know was a place where drugs were. It felt so normal to me. I’ve never asked myself why there were so many junkies around me or why in the bar on the main square of the city, where we used to hang out all day, all the spoons had a hole drilled in. That didn’t look weird to me at all. We used to do drugs, all my friends used to do drugs; some of them died back then and some died later [from] the consequences of drug abuse. I got myself a serious disease, chronic hepatitis, just recently cured here in Rome. Everyone from my gang of friends still bear some scars, but at the time it all felt right to me, and things like police beating us were business as usual. Those things were part of a game with a set of rules we all agreed on.

Then, once you grow up, if you think of 18-year old drug-using kids, it doesn’t feel right to you anymore. It gives me the creeps, you know? And now I can’t help but think, why didn't anybody give us a different example or advice to set us on a better path?

And as far as culture goes, the only thing I had access to was music; my punk rock bands and my friends’ punk rock bands. That’s it. That was all I cared about. I didn’t go to university, I attended two weeks at the Academy of Fine Arts of Florence [Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze], then I punched a teacher and got kicked out of school. Pisa is a university town, me and my friends used to look students from a distance, with great hostility. Existence to us was a high-speed race towards a wall. People who were trying to build something in their lives weren’t worth shit to us. Think how stupid we were! I don’t want my nostalgia to be mistaken with some sort of praise [for] what I used to do back then. But that’s how I was...

So that was my city, the Pisa I remember. And it was a disaster. The only place outside Italy I used to visit at the time was Amsterdam, for obvious reasons. And when it came to drugs, Pisa didn’t seem much different to me, actually.

How did you work on MBDL? Was it improvised?

Yes, and I don’t think it’s hard to improvise if you are dealing with real life, you know? You are not working on the script of a Netflix TV series where everything has to fall in the right place, with the right kicker, etc. No, you just have to surrender yourself to the truth and to all the things that were already there. You just need to dig into memories, trying to be honest with the things you remember. Then you have to be good at choosing what you are going to put on the page, or what you are going to leave out.

Did you cut and paste or was it one single flow?

A single flow. But there is a batch of pages I had to throw away. I have an anecdote here. There was a chapter about the time I spent in jail. I had some strong and interesting experiences there. As soon as that part of the book was done I showed it to Igort—who was my publisher at the time—and he was like, these pages are amazing, the most important chapter of the whole book, it shows a part of society from that time-- So, in a split second, I thought no, I’m throwing this away. [Laughs] Not because he told me so, but because I needed to be honest, especially with the people I met there. Some of them were still in jail. You spent 10 days there, Gianni, you don’t know shit about it. So I threw those pages away, and I wrote a note in a page where basically I apologize with those people and I give a short written version of that story.

I don’t consider it a universal rule, you know, but at the time it just felt better to have some strict moral rule about what I can and can’t tell in my stories. And the fucking basic rule is: only speak about the things you actually know.

When did you realize you could stop and the book was done?

I just felt it was over. I was doing four or five pages a day, but at some point it was just done. There were other stories to tell. If I was smarter, I could have done one or two sequels, as my publisher at the time asked me to. There was enough material to do that. But the important issues were already there: my sister’s abuse, my relationship with women, etc. I remember one day on the subway in Paris I actually saw the final scene of the book: the kid who mimics eyeglasses with his hands. And when I came back home I said to myself this is the end.

And then you found peace.

Yes, yes. One of the effects of working on my personal issues through art is that when I can finally untangle the knots, I find peace and balance, at least for some time. Same as what happened with S. At the end of the book I made peace with my trauma, even if the pain [is] still there right now, but I least it took a different color, it felt sweeter.

War is a steady presence in your work; it is in almost all your books. Where does it come from?

Firstly, I need to make clear that I have no sympathy at all for war. But I am interested in every situation that puts human beings on that thin line between life and death. And I have a huge interest in what can happen to a person under those fucked up situations. I love stories about veterans and about the kind of fellowship that people can experience during a war. I think it all comes down to my teenage years, with their great bonds of friendship that still resonate to my ears in all their beauty.

And there is one more reason. My father’s stories of wartime were my family’s epic tales, and he used to tell them at the dinner table so often. To me, a man born in our consumer society, those tales were so distant. My father was an anti-fascist, he had been through a lot, he was beaten, he had to face the Nazis-- but every time he told those stories there was a spark in his eyes. Maybe, same as for me, it was because those were the tales of his youth, and his youth coincided with seriously hard times.

I’m quite convinced people need to experience hard times in their lives. People need to get up and face hard times, to confront themselves and with harshness. I’m not a sadistic person, I’m just sure that life is hard for everyone. New generations deserve the opportunity to strengthen their backbone. I’d love to see a world where there is no such thing as pain. But that is simply impossible. Everyone now wants to be protected and to protect others from words and actions that can hurt them. I understand that. But it’s impossible to avoid pain, so you’d better get prepared, and if you don’t do that when you’re young you won’t have the chance to do that anymore.

My father’s tales did set an example, the warning of a person who really risked his life and had to make life-and-death decisions. That is probably the reason why when I was young, despite growing up in a wealthy family, I choose to live with people coming from a less privileged background than mine.

I think young people need to question themselves. I feel lucky for growing up without social media, having to confront myself only with reality. I had no way to be appreciated, I didn’t have some hundred strangers telling me how they love what I do. Thank God I didn’t, because that appreciation is not true, but it can lead you to think otherwise.

Looks like working on MBDL, you were also fighting with art - with your own ability to draw in a beautiful way, and along the path of research you’d followed so far.

When I asked myself why there was such a difference between the funny stupid person I was and the bleak and sad stories I was telling, one of the answers I gave was that my stories were bleak and sad because my art process was slow. I mean, in my opinion comedy requires speed of execution. So the first thing I realized was that I needed to be faster in order to [concentrate] on the lines I was writing.

Besides, at the time I was coming from two years spent drawing weekly cartoons for Internazionale magazine, with a simple and sketchy style, and I never had the courage to use that style for a whole book. I was feeling like I needed to show how good I was. It’s a close-minded idea, I know. That’s the reason why I was always changing techniques, I was never satisfied. I’ve always felt the need to push forward. Drawing in a simple sketched style felt easy at first, and only then I realized how hard it was to have a “brut” style that was coherent and didn’t look like shit.

After MBDL you walked away from comics for a few years--

That book brought a kind of attention on me I wasn’t prepared for at all. Now that I’m older, I’m almost sure that success, even a small success like mine-- it’s bad for people. Really bad. It can give you good things as well, but I think that it can be deeply bad.

That book brought a kind of attention on me I wasn’t prepared for at all. Now that I’m older, I’m almost sure that success, even a small success like mine-- it’s bad for people. Really bad. It can give you good things as well, but I think that it can be deeply bad.

After MBDL, all the time I tried to start a new story, I was hearing people’s voices. Voices of the readers. And those voices were asking me to work in the same way I worked on MBDL. I was repeating myself, and I wasn’t feeling true to myself. I was stuck for a long time. And lucky for me, one day Domenico Procacci [Film producer, owner of the production company Fandango] asked me to write and direct a movie, which has always been my dream, because working on a movie is just amazing, something truly amazing. So I dove right into that new project.

My first movie, L’ultimo terrestre [“The Last Earthling” or “The Last Man on Earth”, 2011] was based on someone else’s graphic novel, Nessuno mi farà del male [“No One Will Hurt Me” by Giacomo Monti. I wasn’t able to write a story of my own. Procacci was sure I was going to make a movie based on MBDL, but I couldn’t put my hands on a book I was done with and exploit it in order for it to be more successful. My brain just doesn’t work like that.

How does it feel to see MBDL published now in English after all these years? Things has changed and the book is still a great part of your life.

I’m kind of afraid because I don’t want MBDL to fall into the self-pity genre and into the whole self-pity culture that is pretty dominant right now in western society. I would never ever do a book like that right now, even under torture, now that weaknesses seem to me to be often fabricated, and sometimes are just a way to stand out and attack others. No, that’s not me anymore.

You started the book saying “nothing interests me anymore”, but now what interest you? What has changed?

What interests me? Maybe even less, now. For a few years I made satire and I worked for television as well. I’ve fought ideological battles against ghosts on Twitter, and I used to have quite a lot of followers back then. I was appreciated by people who had the same ideas as mine. I was part of a tribe, a left-wing tribe. All this was easy and dangerously gratifying. Now I am ashamed [of] how I gave myself to that system, and for how I embraced such harmless battles.

I left the world of TV and Twitter and Facebook. I have such low regard for that kind of social media now.

Now I care about the people I love, people in flesh and blood, and nothing more.