Mrthyu. Maranam. Savu. Maut.

These are some of the words representing Death from the hundreds of languages on the Indian subcontinent.

Death is important to us all. Death matters. Death defines and shapes us, now and forever. Death never leaves our side, for it is the ultimate companion of humankind. That which we know and dread from our first breath up to our last.

So how do we define such a companion? How do we give shape to such a figure and force so primal and primordial and yet so intimately familiar?

It’s a question that’s haunted all of humanity since the dawn of time, as the very idea of Death has been granted divine stature across myths and belief systems throughout the world. It’s been viewed and presented in ways both universal and yet also specific via idiosyncratic cultural lenses and context. Death is essential to all our mythologies, for it is the one eternal constant, the absolute that none can escape.

Death is that familiar face and that distant stranger rolled into one. The Greeks saw it as an almighty winged force in the form of Thanatos. The Egyptians saw it as the canine-headed guardian Anpu (or Anubis). The Mesopotamians viewed it as the lion-mace wielding warrior Nergal.

And when the Black Death plagued Europe in the 14th century, people brought forth a now all too well-known image: the Grim Reaper. Our presentations of Death tell us a great deal about us and the worlds we inhabit. Death is a useful symbol of expression.

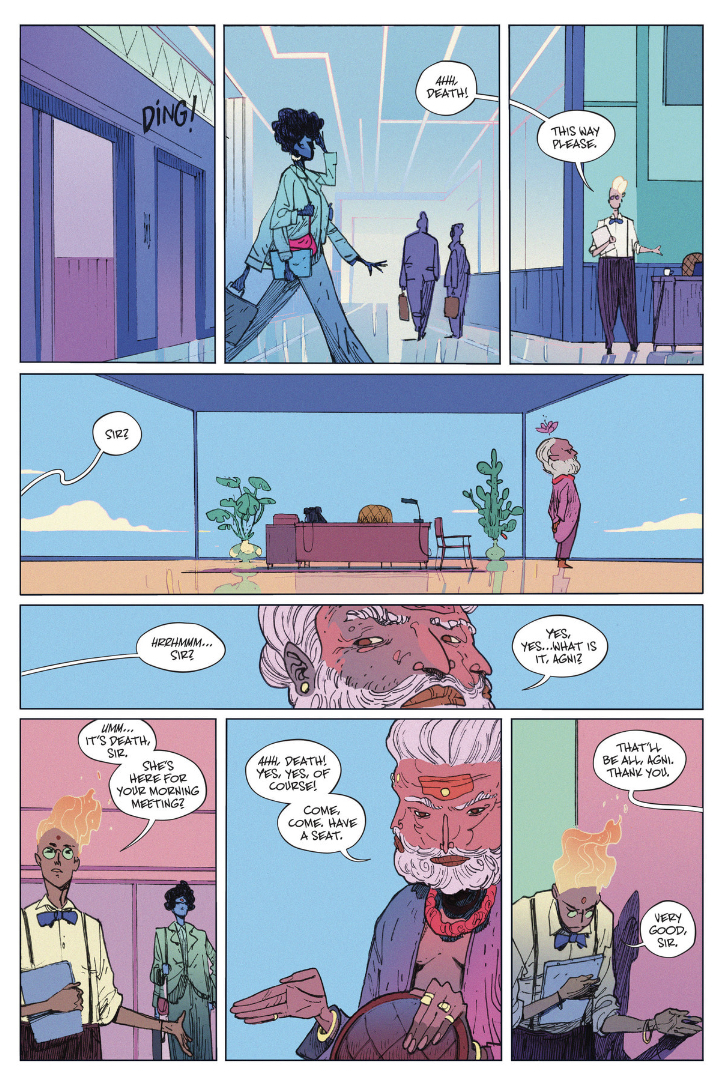

Which brings us to The Many Deaths of Laila Starr, a five-issue miniseries by the creative team of Ram V, Filipe Andrade, Inês Amaro & Deron Bennett's AndWorld Design. Serialized by BOOM! Studios in 2021 and collected in 2022, the book follows Death descending down to Earth to live in mortal form, becoming flesh and blood rather than mythic idea.

The book spans an entire lifetime, charting Death’s various interactions with one man from the beginning of his life to its end, as each issue becomes about a key stage of life. The man is Darius Shah, a child prophesized by the gods to invent immortality, thus eliminating the need for Death and resulting in her mortal descent to begin with. And so the whole book is Death’s pursuit of this boy who is destined to erase her, in order to erase him first. But of course it isn’t so simple.

Life never is.

In the world of Western comics, there have been many visions of Death, from Jim Starlin’s skeletal figure to Jack Kirby’s foreboding Black Racer. But one vision of Death perhaps stands out above all others, subsumes all, and is considered the definitive icon in Western comics.

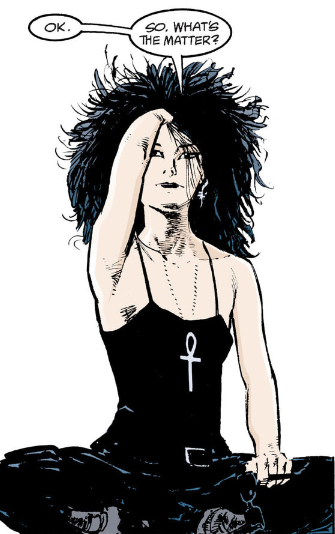

Neil Gaiman’s and Mike Dringenberg’s vision of Death from The Sandman. The standout and star character from the legendary Vertigo series stands tall, towering above all others, perhaps more than ever now given the latest Netflix adaptation, featuring the magnificent Kirby Howell-Baptiste in the iconic role.

And it’s a vision of Death that also tells us something, being so attuned to the creators that brought her to life.

And there’s a touch of wish fulfillment in there too. I didn’t want a Death who agonised over her role, or who took a grim delight in her job, or who didn’t care. I wanted a Death that I’d like to meet, in the end. Someone who would care. Like her.

- Neil Gaiman, from A Death Gallery (DC/Vertigo, 1994)

The Gaiman/Dringenberg Death was very much a specific personal expression of the idea reflecting a period and moment in time. Based on Dringenberg’s personal friend Cinamon Hadley (who sadly is no longer with us), she feels like a vision of Death you could see performing next to Siouxsie Sioux. Death is cool, like a slick musician who could perform like a star, but a second later would sit down and listen to your problems, understanding. It makes sense. She was a perfect avatar for the Goth subculture that emerged in the '80s and was still on the rise in the early '90s when Gaiman co-created the character. She’s a perfect modern Western construct of Death.

It’s a lovely, magnificent take that deserves the stature and adoration it has.

But it’s not all that can be done. It is, in the end, but one way to broach Death. A very good way, and perhaps the end-road of that specific path and way of doing it, but there’s still infinite room. There are yet other ways. You can change the context and lens on the idea, and you’ll end up with drastically different results. You go to Japan and explore manga, and you’ll find the idea of ‘Death’ is a different one there. You’ll find shinigami in a number of comics, the Japanese cultural idea of Death Gods, because the cultural context of places and people and how they vary, the moments in time they’re made, can lead to drastically different results, despite the universality of dying. There’s an endless world of possibility.

The shadow of Neil Gaiman and his Death from The Sandman hang over The Many Deaths of Laila Starr, understandably; there’s just no getting around it. Particularly given writer Ram V is deeply influenced and informed by Gaiman’s The Sandman and Vertigo in general. But what Ram V and Filipe Andrade do is what those classic Vertigo creators themselves would do - they embrace it and then move forward, building something new, by bringing themselves to it, making it utterly inextricably personal to themselves. The way Gaiman and his own collaborators did when they constructed their vision of Death.

So what is Death in a contemporary world of the 2020s to an Indian writer like Ram V? What does making it personal lead to in the case of Ram V’s work? It’s the question animating Laila Starr, a book set in Mumbai, where Ram originally hails from.

And so what you get is very much a post-Gaiman/Vertigo take on Death that is in line with a long tradition of Indian cultural stories about Death.

Specifically, you get the Tale of Yama’s Descent as filtered through a Post-Gaiman lens on Death.

Almost every belief system around the world has its own equivalent of the "psychopomp" - beings who guide the souls of the dead onto what awaits them next. In Hindu mythology, this role is performed by Yamadutas, which roughly translates to ‘Servants of Yama’. And Yama is the Lord of the Dead. He is the King of Naraka (Hell), who supervises them, alongside his assistant god, Chitragupta, who keeps a record of all the dead.

Yama is prideful, powerful, and an almighty ruler, who rides his vahana (vehicle) of the Buffalo. He is the basis for the Buddhist iteration and conception of Yama as well, as both understandings of the legendary Death King co-exist, with many views swarming around the supervisor of all the dead. But in a strictly Indian context, where Hinduism is the religion of the majority, the popular conception and vision of Death and the Death God tends to lean towards Yama.

And there is a long tradition of a certain kind of story with this immortal lord - the tale of his descent down to the mortal realm. It is a fairly common tale in Indian cinema’s history. You can even go all the way back to Prafulla Chakraborty’s Jamalaye Jibanta Manush (1958) starring Kamal Mitra as Yamraj (King Yama) and Bhanu Banerjee as the lead. A Bengali romantic comedy, it was in itself based on Bengali writer Dinabandhu Mitra’s story of the same name.

But perhaps more than anywhere else, the tradition and tale of Yama’s mortal descent is most prominent and popular in South Indian film. Chakraborty’s aforementioned JJM would go onto be remade only two years later in the southern languages and film industries of Telugu in Devanthakudu (1960) and Tamil in Naan Kanda Sorgam (1960) respectively. Both would be directed by the same man: C. Pullayya (among the earliest South Indian filmmakers, going back all the way to the 1930s), an indicator of the two languages and industries’ historic, nigh sibling status that continues to this day. Both films would star iconic Southern actor S. V. Ranga Rao as Yama, him as the commonality amongst two different and separate casts across two different languages. The legendary Tamil comedian K. A. Thangavelu would play the lead against Yama, whilst the legendary Telugu icon and star N. T. Rama Rao (NTR Sr.) would play the lead in the Telugu iteration.

You can even skip almost two decades, and come to NTR Sr.’s second effort in the enterprise with director T. Rama Rao’s seminal Yamagola (1977) starring Kaikala Satyanarayana as Yama. That would go onto be remade into Tamil by D. Yoganand as Yamanukku Yaman (1980) starring the beloved Sivaji Ganesan as both the lead and Yama, whilst even the northern Hindi industry of Bollywood would remake it with its original Telugu director as Lok Parlok (1979) starring the iconic Jeetendra, with star Premnath playing Yama.

Heading closer to the '90s, there’s Ravi Raja Pinisetty’s Yamudiki Mogudu (1988) boasting the legendary Telugu star Chiranjeevi as the lead, with Kaikala Satyanarayana once again as Yama. The pan-Indian icon and legend Rajinikanth would star in its Tamil remake Athisaya Piravi (1990), starring Vinu Chakravarthy as Yama, overseen by director S. P. Muthuraman.

Hell, even in the modern age, S.S. Rajamouli, the director of the recent global phenomenon RRR (2022) and the Baahubali duology did the definitive modern cinematic take on the subject with Yamadonga (2007) starring N. T. Rama Rao Jr. (who plays Bheem in RRR), the grandson of NTR Sr., paying homage to his lead star’s iconic grandfather and his film Yamagola. This would star popular veteran Telugu star Mohan Babu as Yama, and would even feature a whole meta-sequence alluding to the wider, rich history of Yama stories on movie screens.

The thing about each and every one of these films across the decades though? They all feature, essentially, the same common story. They deal with Tricking Death. They usually almost always feature a mortal who has been the victim of some manner of misfortune and ends up dead in Naraka (Hell), the kingdom of King Yama. And then begins to outwit and screw with Death himself, until the mortal finds a way to restore their life, and helps bring Death down to deal with him. And by the end, after all is said and done? Death, who has descended down to wait it out, because he’ll have this mortal in the end? His heart melts, or by some manner of trick or binding law, Death must relent and let the mortal live on, and does so with a grin and a measure of pride. Yama is almost always played by a proven veteran actor who can bring gravitas and weight, being the kind of role that in the West you’d cast serious thespians for.

The tale of Yama’s descent is almost always a sentimental one, a silly one, wherein the cold-hearted, tough and stubborn Death is baffled, confused and annoyed by humanity and their day-to-day; all their rituals and ways of living. Yet by the end Death proves to be a dear softy, who says ‘Alright, you. Go on then, live. Live. You’ve earned it.’ The appeal of this classic, tried-and-true story is of man’s bartering, cheating, and ability to evade Death and rise above the impossible, to accomplish the unthinkable. Man wrestling with primal, universal forces and achieving victory through the most human impulse - the fundamental need to survive. They’re tales that prove even Death has a heart and conscience, or at the very least laws, which you can play by to make it work.

They’re stories that have been performed by icons of South India, from the grandfather of RRR’s Bheem in NTR Sr. to the father of RRR’s Ram in Chiranjeevi, to even Rajinikanth - who it’s impossible to be Indian and not know.

Ram V comes from a Tamil background, and these are stories that are familiar to many with South Indian roots. Laila Starr certainly feels like it draws on this tradition, or at the very least is keenly aware of it, whilst also drawing a ton of influence from the fearsome nature of Kali.

But there is another king, another god who descends down to the earth, who walks among the mortals. Another lord whose tales of descent we know all too well.

You’ve all heard the word ‘Avatar’, whether it be due to the Airbender cartoon or James Cameron’s obsession with Unobtanium. This is the figure it all comes from. Vishnu is the king of Vaikunta, eternal impossible divine plane above even Svarga (Heaven) itself, which is ruled by Indra. Vishnu, aka the Avatar, is one of the Trimurti: Brahma the Creator; Shiva the Destroyer; and Vishnu the Preserver. Brahma creates all. Shiva will destroy all, in his ultimate Dance of Destruction.

But Vishnu? It is his task to preserve and protect all that is until that opportune moment arrives.

And so he descends down in mortal form every time the world requires it, whether it be as a fish during a Great Flood of the world or as a Lion Man to slay an unkillable demon king. But regardless, the fundamental purpose of the Avatar's Descent is said to always be the same - to restore balance to the world.

The Preserver of Life is prophesized to have 10 Avatars, with 9 having already occurred, from Ram in the epic Ramayana (the 7th Avatar) to Krishna in the Mahabharata (the 8th Avatar). The 10th and final Avatar is said to be one that is yet to come, the Avatar of the Apocalypse that will emerge upon the eve of the end on a white horse and help restart the cycle of the universe. Kalki: he who shall arrive before reality reboots, essentially.

So the myth exists at this careful precipice of ‘preserve life’ and ‘end life’ itself, as the majority of these tales are driven by the Avatar coming down to take out one tricky figure in the mortal realm. For instance, Narasimha (the 4th Avatar), Rama (7th Avatar), and Krishna (8th Avatar), which are the three most popular ones by far, are all the Avatar descending down to the mortal realm to deal with demonic tyrant kings of the mortal realm which nobody else can stop. Narasimha and Rama especially were Avatars practically designed in a celestial lab to evade the ‘loopholes’ that made the tyrant kings impossible to harm or kill, as usually these wicked men held divine boons that made it impossible for regular gods or demons to slay them. So Vishnu-in-the-form-of-man is the kind of technicality that let the messes of the divine world get cleaned up.

And this influence is evident in Laila Starr as well, as Laila too descends down in special pursuit of her man, the man who will invent immortality and ruin everything. She arrives via a mortal avatar to take down Darius Shah, that pesky mortal who’s gonna make mankind immortal.

Ram V made no attempt to hide the obvious baked-in influence and DNA from these stories in an interview I had the chance to conduct:

I think I had come up with various versions of that story long before I even started writing comics, to be honest. There were early versions of short stories where it was “Krishna comes down to Earth!” and whatnot, but I suppose it really turned into Laila Starr when I had this kind of need to write about death, even as a teenager.

And it makes sense, particularly as the symmetry of ‘God in human form in pursuit of a pesky mortal’ fits both the Avatar and Yama, albeit in very different ways, and is just a classic mythic story and structural framework.

But it also makes just as much sense that Ram V would in the end abandon the actual specificity or having to deal with the baggage of such explicit mythic repetition with the gods, given the increasingly pernicious situation with Hindutva and how Hindu myth intertwines within that. The myths come with a long, heavy baggage that you just do not need, in all honesty, to tell a smart genre story.

It is better, wiser, to take inspiration and ideas rather than root oneself too strongly and explicitly to these things or make work specifically about them, given the realities at hand.

And it’s what Laila Starr does.

It never specifically tells us that ‘Death’ is ‘Yama’ or ‘Kali’ or what have you, because that’s not the point at all. She has no name, and is instead just referred to as ‘Death’ in the book. And it’s because the specifics don’t matter, all that matters is the rough abstracted idea she represents. It’s less about any specific myths, and more so something that takes and is informed by aspects of all of them to do something completely new. It makes something contemporary from the husks of the past, rather than being too bound up in what came before.

Moving forward is the priority.

Being rooted strongly in myth, but not being about the myth itself is, of course, not new for Ram V works. Instead, using the myths and ideas as metaphors, to interrogate wider, deeper subjects and terrains of people and their existence - that’s always the more consistent fascination. An interest and investment in people, with myth as merely a framework to explore that. V did it to great effect in another five-issue miniseries just a few years ago via These Savage Shores (Vault Comics, 2018-19). TSS was rooted in the myth of the Raakshas, ancient immortal Hindu beings, used as a metaphor of an Old India and as a symbolic construct to talk about changing times and Colonization, as represented by the arrival of British Vampires. The collision of these myths was in service to bigger matters. Laila Starr follows in that path.

But there’s just one major distinction.

If These Savage Shores was about our ultimate nightmare, our greatest horror, our cultural trauma as a people and the eternal gaping wound that hangs over us, Laila Starr is the opposite. These Savage Shores was about our doom, about the inevitability of it, about how it haunts us, an unimaginable tragedy and loss incalculable and impossible to measure the burden of. Laila Starr is not about our doom.

No, it is instead about our dignity in the aftermath of that doom.

It is about how we live on ages after that horror we endured. It is not our nightmare, but so much more. It is not about our historic trauma, but about our lives in all their color and splendor, with all their absurdities, contradictions, laughter, joy, and heartbreak and loss.

It is about our endurance.

It’s a book that feels like it could’ve only been made after Ram V made These Savage Shores, evidently, but it’s a book that feels like it could only exist after another one of his works - Grafity’s Wall (Unbound, 2018; Dark Horse, 2020).

Set in the streets of Mumbai, Grafity’s Wall (art by Anand RK, lettered by Aditya Bidikar) was about a group of young people with all their big, bold, colorful dreams. The book explores their youthful passions and pursuits, and by the end cuts ahead to reveal where they’ve all ended up as adults, contrasting dreams with actualities. It is a book about growing up in Mumbai, about Indian life and youth. It is, above all else, a book about Indian dreams. It is in stark contrast to These Savage Shores, which digs so deep into pain and horror. And Laila Starr reads like a work that comes from the experience of having done both of those, weaving together aspects of both. He’d done the big genre exploration of the ultimate Indian trauma, and he’d also done a pure drama of youth without any genre elements. In Laila Starr, they find synthesis.

Once again, Ram V returns to Mumbai to explore Indian life and dreams, but rooted in genre elements with a mythic, immortal figure - and much more sprawling than either of the prior projects. This is a book about the entirety of life itself, not just one slice or two. It’s the totality of it, a grand statement on Indian life and existence from the first breath to the last.

It’s evident from the very first page, in almost striking contrast to These Savage Shores.

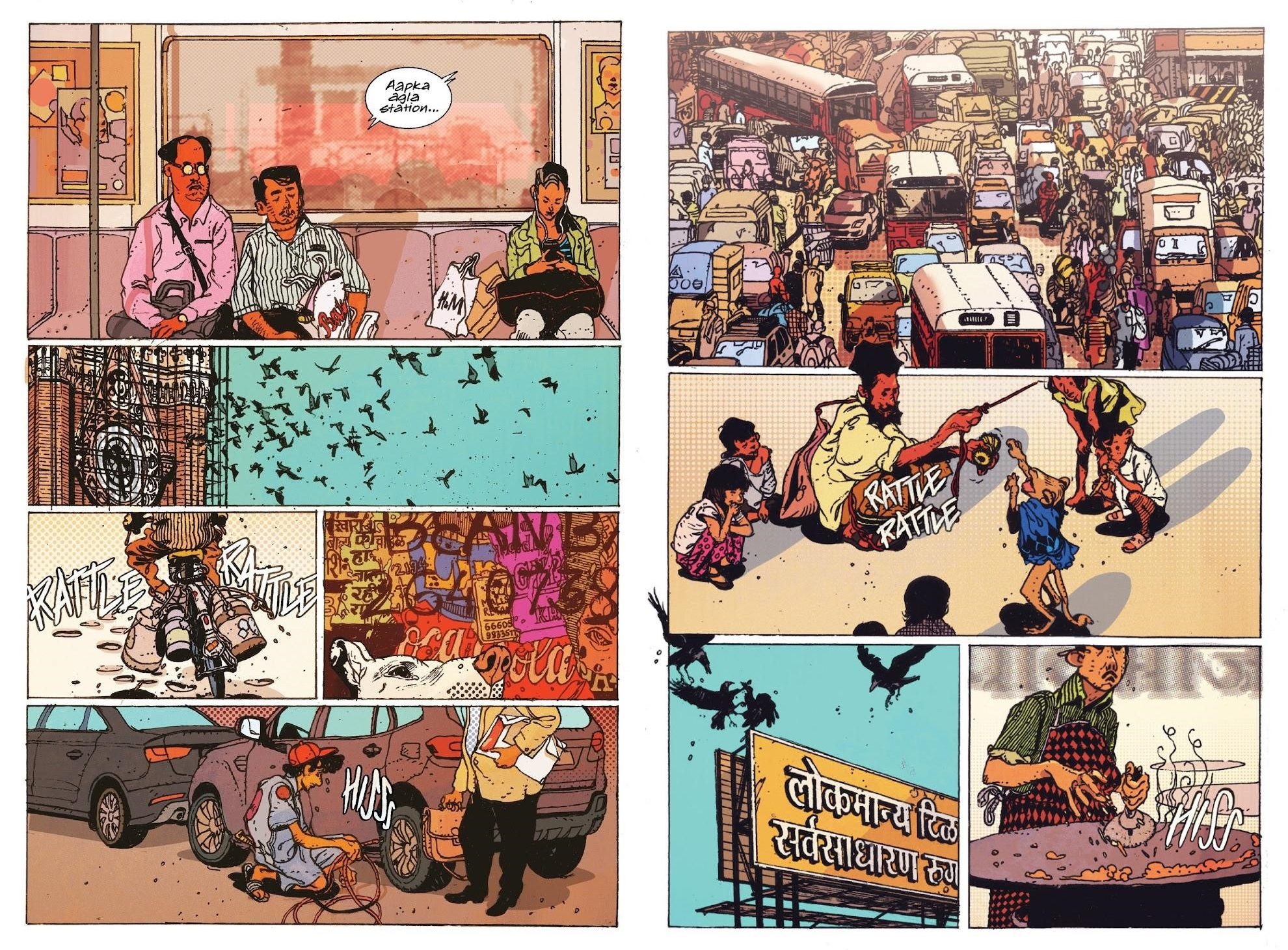

Instead of the confining, rigid structure of the iconic Western grid, Laila Starr opens on an expansive splash page. It’s not people trapped and imprisoned in something, in largely muted gothic tones like TSS. It’s a sprawling canvas of busy activity and possibility, a world that looms large. Unlike the reality of controlled colors in TSS, where the most standout are the purples of the night and shadow, and the blood red of battle and violence, here we see a world and reality exploding with all manner of colors. And it proves true throughout the entire story, as Andrade & Amaro construct a reality of cacophonous hue.

It’s closer to Anand RK’s work on Grafity’s Wall.

It is the hustle and bustle of city life in Mumbai. But at the same time, notice how it differs. RK’s work has a sense of solidity; everything he’s drawing, in the way he is, gives a sort of tangibility and physicality. You can hear the solid RATTLE of those milk canisters, the shaking metal as the man rides his bicycle in the rush of morning. You can hear the HISS of the ingredients cooking on the hot stove, and you can feel the earthy city these people live in. The color palette and aesthetic sensibility present a grounded reality that’s down to the earth, one with grime, dirt, and graffiti, like a street you could pass by.

Laila Starr may lean towards Grafity, but it is also not the same.

Andrade’s art, with Amaro’s color assists, opts for a more abstracted, fluid style that eschews ‘grounded’ reality for a more vivid, fluid one. If Grafity is how Mumbai looks, drawn by an artist who has an intimate sense for it, Laila Starr is much more about how the reality of Mumbai and Indian life feel, drawn an artist who’s only visited the city as a tourist, and beyond that is working from reference. And the abstraction and leaning into the fluidity fits, given it is a genre book drawing upon myths and gods, and reality as seen and experienced from their colorful perspective. It is a world where myth and mortality mix, in a colorful blaze of possibility and power, wherein the earth reaches out to meet the sky.

So what you end up with is a buzzing, breathing, expansive vision of the Indian world. It extends out, free, in loving embrace of Indian life.

But what is Indian life? What does that mean or entail, really?

If Grafity’s Wall was the perspective of a bunch of young Indian kids and their dreams against the backdrop of Mumbai, like children looking upwards into the sky, then Laila Starr is the opposite. It is the perspective of an ancient immortal idea looking down from the heavens, trying to understand us regular people. It is a work about the intersection of myth and mortality in modern Indian life.

And it is why if one observes carefully, they will notice that each chapter is set around a different period of one’s aging and development, and is built amidst the background radiation of something specific to or about Indian culture and life. The work is universal in its exploration of big ideas like Life and Death, certainly, but the actual specifics and contexts upon which it all takes place informs and gives further texture to the story and what it really is expressing.

The first chapter contextualizes Indian existence to us via explicitly Corporate Hindu Gods; we see Death in a business suit, in a capitalistic abode above, wherein Brahma the Creator is effectively a CEO, and Agni, the fire god, is his personal assistant and secretary. This is clearly in line with a number of ‘systematized’ visions of universal forces and impossible concepts, wherein our own capitalistic realities are imposed upon myths themselves. And there’s precedent too, given how much most filmic takes on Yama and Chitragupta are that of a CEO/Boss and his personal assistant or secretary who keeps all his records and schedule. It’s not a far stretch or extrapolation from that to get to this. Besides, it’s all terribly funny because of the sheer absurdity of it all.

But there’s something more going on here. India was colonized and captured and held via imperial power of the East India Company. Though later the United Kingdom would officially take charge and power over India, it wasn’t a nation that conquered India. It was an independent British company, granted power by the Queen in the year 1600. It was a capitalistic enterprise that put us in chains and emptied our riches and destroyed our fates and futures. Capitalism is how we were colonized.

And here are the gods of the country’s majoritarian faith, all dressed up in corporate clothing and steeped in corporate culture, capitalistic as all hell. It’s funny, yes, but it’s also deeply biting:

Look at how we celebrate the very thing that destroyed us to begin with. Even the gods, mythic constructions of universal forces, are fashioned along that destructive system’s likeness.

I think about that a lot, the idea of the Indian embrace of capitalism, when it is what laid waste to us. It’s hard to ignore when looking at, say, the astronomic rise and prominence of Gautam Adani, who now sits among the richest people on the planet right next to Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. We love capitalism, we love capitalists, and we’re the gears that help turn its engines, it seems. We love it even as it kills us, even as so many of our own have so little and keep losing it, as others who already at the top keep gaining more and more.

Perhaps it is right then to have and depict Corporate Gods for a corporate culture like ours. Of course the gods learn that Death will no longer be relevant due to a boy inventing immortality, and they fire Death. They don’t care, because why should they? Death is a pain in the arse. Death is an obstacle. Death gets in the way of work. Death is just sleep you don’t wake up from. And too much rest is bad for corporate, that’s the nightmare for capitalism. The abolition of Death is, if anything, a capitalist dream made manifest, as the workforce can forever keep on. Eternal labor to keep things running. It’s preferable, it’s profitable. It’s more efficient.

Of course a corporate cosmology is the inevitable endpoint.

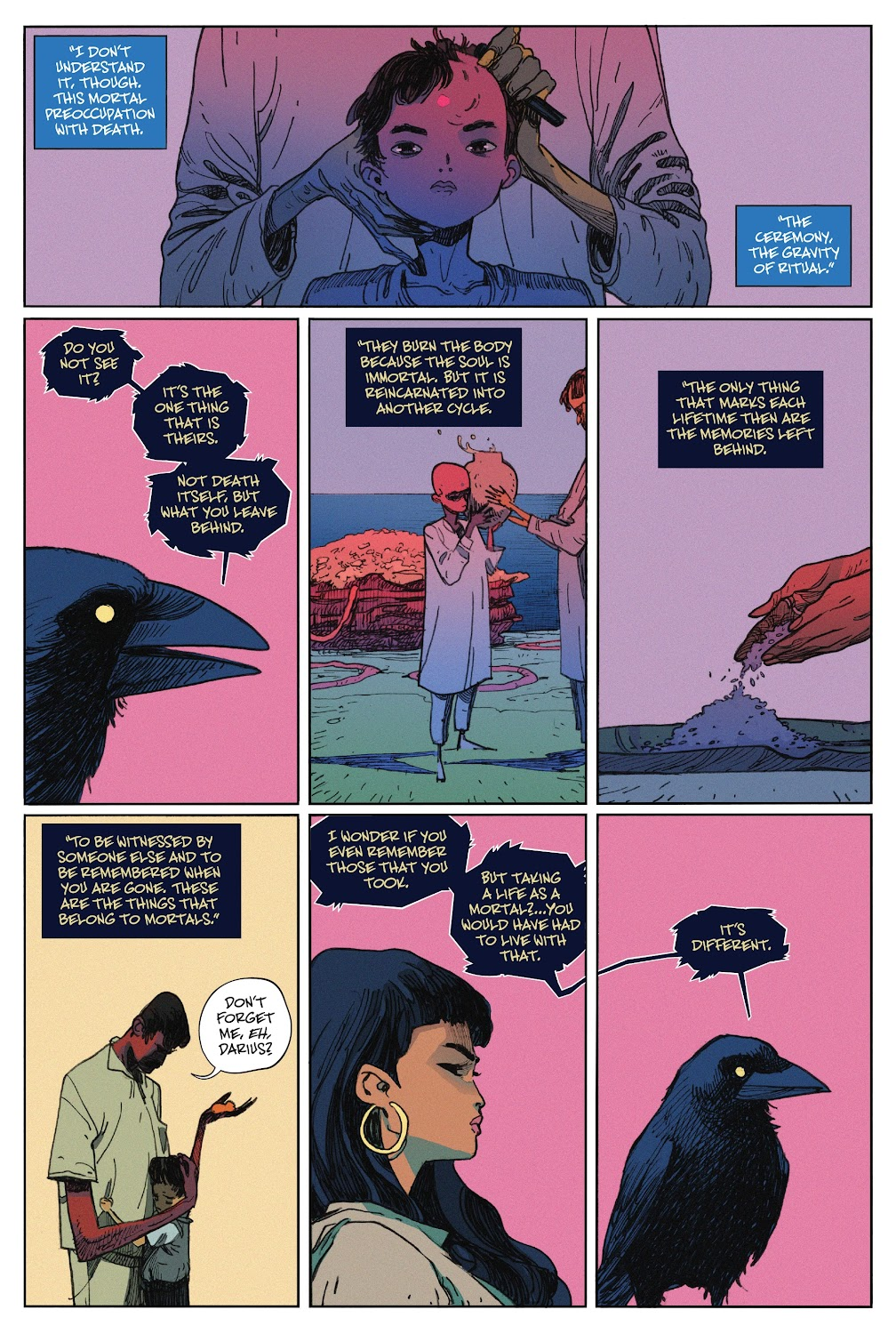

The second chapter dives into Hindu funeral rites and the Casteism that is rife in contemporary Indian life. In an issue dealing with childhood, the boy Darius Shah, said to one day invent immortality, is no older than 8. He’s born into a fairly well-off family, one that clearly had generational wealth of some measure, owning a sizable bungalow on the outskirts of Mumbai, equipped with a whole field of mango, jackfruit and sapodilla trees. It is where Darius’ grandparents lived, while Darius and his own parents would eventually move into a posh gated community full of security squads, elevated views, tennis courts, and other amenities enjoyed by well-off people. But before that move, we get to see young Darius meet a man the Shah family hires to help tend to the fields - a man from the south by the name of Bardhan.

Bardhan grows to be Darius’ dearest friend and companion through his time there, as the boy loves this hard-working man, capable of so much. And every summer when the jackfruit would ripen, Bardhan would spend all day getting them down and preparing them for the family to eat, use, cook, and enjoy. But he was not given any for himself - he was only ever served boiled rice, a stew, and some milk. And neither was Bardhan allowed to step inside the family home or use any of its facilities under any circumstances. He had to keep to a porch in the back, cleaning up outside before he left.

And when young Darius questions his mother why they can’t save some jackfruit for dear Bardhan, she chastises the very thought, telling him they are not meant for Bardhan, and that Darius shouldn’t encourage Bardhan to think they are.

It’s evident as to what’s going on here, because, see, the Shahs are a well-off family and clearly belonging to an upper caste in relation to Bardhan, who has to work tirelessly for very little, only to be treated the way he is. A man who will not even be permitted to use the bathroom because of who he is, in relation to whom the Shahs believe they are. He just has to take and live with whatever they trot out outside to him while he works endlessly. It’s very much a deeply ingrained, baked-in Casteism in play, wherein arbitrary lines are drawn, absurd beliefs are practiced as law, and people are divided up into hierarchies, and humanity seems an absent idea. And it’s all normalized; it’s why the mother doesn’t just say no to Darius’ proposition, she adds that he must never allow Darius to think otherwise. The very idea is forbidden. It is fostering an othering hierarchical poison via numbing normalcy. We are us, he is them. We are not the same. This belongs to us. Why would we share? Why should we share? We own this. We earned this.

It’s insidious thinking disguised as innocence, passed down to children like nothing, like it’s just the laws of reality, of how not only the world works, but should work.

But of course, Darius, young that he is, doesn’t listen. And in one of the book’s most touching and delightfully moving sequences, he runs out to Bardhan bearing jackfruit in defiance of all he’s been told and taught about things. He doesn’t care. He just cares about Bardhan.

And the motif repeats when later on, after the Shah family has moved on to live in a gated community, that Bardhan has passed away. They’re told of a funeral that is being organized, and when Darius asks, he’s told that it would be improper for them, their family, to go and attend.

Darius doesn’t care. He’s devastated and distraught. Bardhan was an impossible, larger than life man he loved and cared for. He thought Bardhan would live forever. But Bardhan is gone. And so Darius runs to his funeral on two tiny little feet, not caring about any customs or rules that dictate how he should act in relation to others.

It’s a beautiful, lovely illustration of how human bonds and connections transcend any and all limits, even imposed insidious ones like Casteism. And all the while, doing that, the book also touches upon the Hindu funeral rites involved when saying goodbye to a loved one.

From the son getting his hair cut to bearing a pot of oil on his shoulder, with which he will walk around his father, down to the rice offered up to the crows. These are all images I’ve known all my life, but have never seen put to the comics page, until this book came along. They’re visuals and motifs and real aspects of the rituals people perform, and as such carry profound weight and power. They hold immense meaning. It’s why Kah, the Funeral Crow, speaks on how and why these rituals matter, because we get to choose how we remember our loved ones, we get to honor and celebrate them and their memory the way we like, and perhaps how they may have wanted.

The soul burns like the primordial flames it was birthed from, and so in flames is the soul revealed, becoming one with fire. The body ceases to be, while the immortal soul lives on, and so the remnants of this life lived are for those remaining to reckon with. It’s beautifully real things to many people and their lives depicted with grace and dignity and understanding.

Of course, the comic isn’t explicitly about Casteism and Caste or Hindu Philosophy or the nitty-gritty of the rituals around Death. It’s not a treatise on that, but rather a potent human story of connection framed around a world full of that. But the work is well aware and understands that to broach the terrain it does, in dealing with the cultural context and realities it does, it has to be honest. It’s why while it is not about Caste, it has to address the reality of Caste, it is why while it doesn’t explain every action and its meaning in the Death Ritual to those unfamiliar, it depicts what it must to get to the truth. It’s considered work that treads a number of territories with care, doing its best, as it tries to weave a portrait of Indian life and culture.

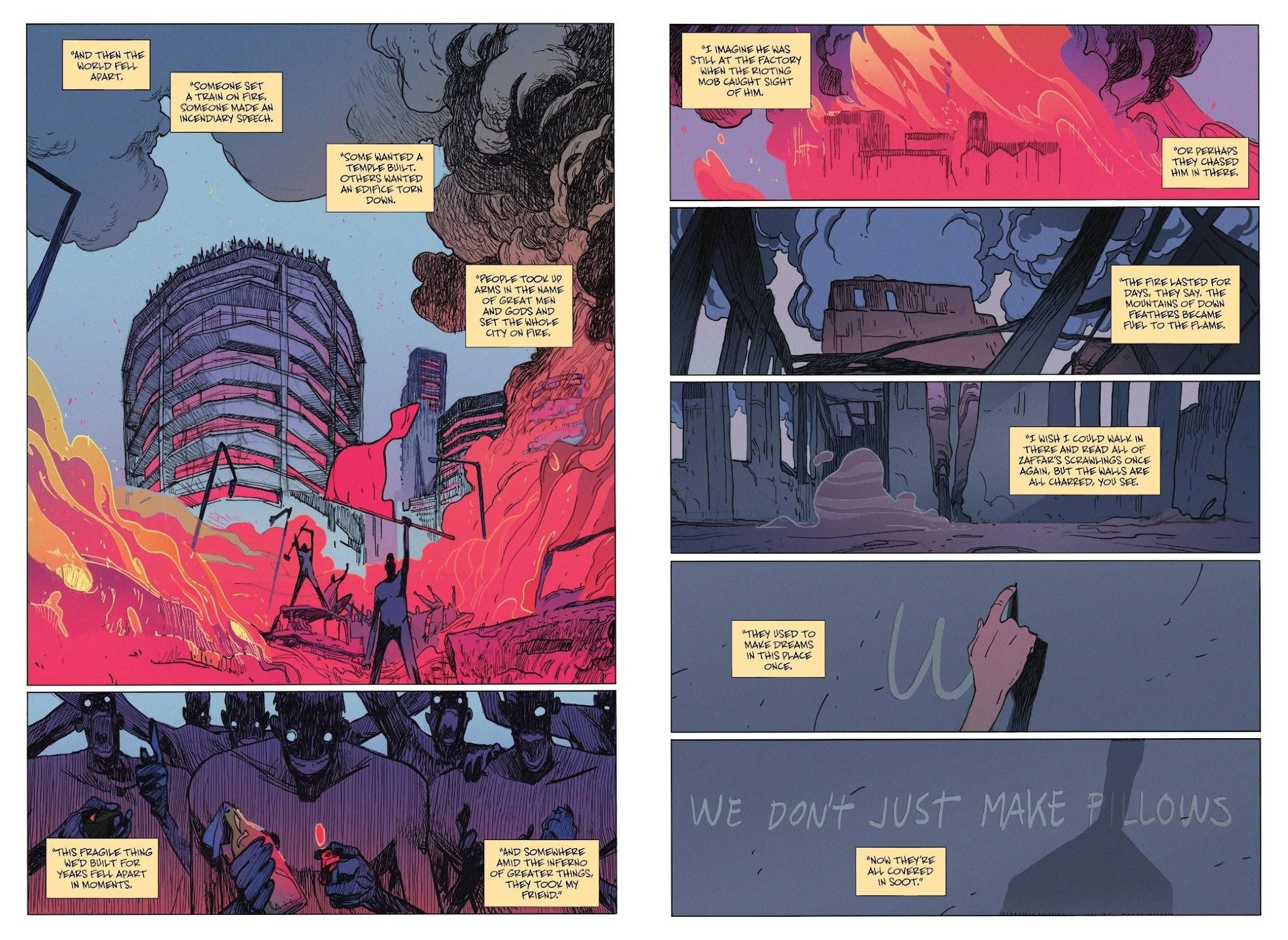

And that, of course, means confronting India's ugly realities and monstrous qualities, which is what chapter three does with its background. In an issue about young 20-year old Darius, we’re given the moment of his first break-up with his first love, Danika, at a party. And then the book cuts back to slightly younger days, wherein we’re introduced to Darius’s best friend, Zaffar. Danika, Darius and Zaffar all used to hang together at the abandoned remnants of a pillow factory built in the 1980s.

WE DON’T JUST MAKE PILLOWS. WE MAKE DREAMS, read the motto of this abandoned Mumbai factory.

Here they all loitered, laughed, argued, fought, drew and cried. Until they didn’t.

The factory was burnt down, until nothing remained, not even the words inscribed in the walls, much less the drawings and art pf these young people. And in the flames, Zaffar was consumed, never living into his 20s. A young life lost and taken away in a horrible, cruel manner. The loss destroys Darius, and leaves him a hollow shell of himself. He’s broken, deeply - no longer is the person he once was. And it’s for this reason that Danika breaks up with him, for while she loves him, she doesn’t think she can continue to be with ‘half a person’, and must move on. The loss of young friendship and a first love is fairly universal as a story, evidently, and those reading chapter three on just that level alone can appreciate the work.

But the crucial context adds a whole layer of extra meaning on top of everything.

The fire? The fire’s source and root was evidently a Communal Riot.

For those unfamiliar with India, Communal Riots have been haunting it for decades, and in recent years have only grown more and more, as India has been swept by a wave of Hindutva madness, with bigots screaming how India is a ‘Hindu nation’ and ‘should be for Hindus’ and taking up arms to ensure Hindu supremacy, all framed in terms of ‘self-defense’ against the imagined boogeyman of Islam and the Muslim citizen.

It’s reached a whole new height under the current regime of the Bharatiya Janata Party (the Indian People’s Party), aka the BJP, which has been ruling the country for almost a decade at this point. The BJP began as the political front of a much, much older organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which is a far-right extremist group advocating for dreadful Hindu Nationalism. It is the organization that the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi was an agent of, and the organization which, in light of that event, was banned. It is a product of Indian right-wingers looking to European Fascism, specifically Italian Fascism under Mussolini, and deciding that was very cool and should have an Indian Hindu equivalent. The RSS is a militaristic organization modeled after those classical fascist groups which armed and trained young men and indoctrinated them, rather like a cult, under the banner of something supposedly benevolent.

The organization made a slow comeback over time, and formed the BJP back in the 1980s, eventually taking more and more power, until it now basically runs a lot of the nation. The current Indian Prime Minister, Narenda Modi, is a member of the RSS, and Hindutva demagogues are all the rage now. Modi and Donald Trump, if you couldn’t guess, got on great. And that’s who India is ruled by now, alongside his nationalistic cultists who accuse any who stand against them as ‘anti-national’ and as an enemy of India itself. You can’t turn anywhere without encountering their vile rhetoric with a special combo pack of Islamophobia to top it all off. Their rhetoric causes real harm; it has repeatedly taken countless lives, and is at the root cause of so many of these Communal Riots.

And it’s the trauma of the Communal Riots that haunts this chapter, even if the book as a whole isn’t devoted to exploring that as its central subject. Its horror and impact is a very real thing in Indian life and culture, and it lingers heavily. It does to us what it does to Darius - it breaks us. It divides a nation, a people should feel whole, into no nation at all. And the lives lost in the feverish fury of these monsters? They’ll never come back. So many siblings lost forever, and all for what? So some zealot feels something resembling happiness somewhere, because they don’t know how to feel anything else? Why? What is the point? What is the bloody point?

To write a book set in India at the intersection of myth and mortality, whilst leaning on Hindu influences? It means you inevitably have to contend with and work the contemporary reality into the story, in some measure or another. It has to be reflected in some capacity in the work, otherwise you’re leaving out something crucial, something real that is so essential to this subject, because what these riots are is the prime intersection of myth and man. Men and their deployment of myth; men and their obsession with one interpretation of myth, wreaking havoc and doing untold damage. So Ram V must deal with it and integrate this truth into his work, if he is to attempt to express truth about life in an Indian context.

And of course, the choice of a factory burning down, an abandoned factory of the 1980s era that is literally inscribed with the words WE MAKE DREAMS? The point couldn’t be blunter. Dreams die here, in abandoned factories, whilst lives burn for the profit and pleasure of powerful monsters. It makes sense, for after all it is the likes of Modi and his BJP who are some of the best backers and supporters of hyper-capitalists and exploitative businessmen like Adani and many of his peers. They are the ones letting his climate-destroying company take over indigenous lands. These are the gang of cronies that would sell everything in sight, including any pretense of their own dignity, if that meant they’d make their money. Profits which could feed millions for generations, but will never make their way over to those people in need.

These are the people that let legions suffer and die and burn during the pandemic with horrible mismanagement and lack of care. They care more about their elections, their money, their name and fame, their power and stature, than about any actual lives of the people they’re meant to care for. They’re corporate stooges and cowards, stoking nationalism and religious division, because it’s just good business for them.

So perhaps as the book framed it in the beginning, Corporate Hindu Gods is just right. Perhaps it was apt and scathingly accurate about these slaves to self-interest.

Jumping from all that, the haunting horror of these zealots and demagogues who preach a certain narrative and construction of ‘Indian identity’, Ram V and his collaborators decide to offer an alternative in the fourth chapter. The vision and perspective of monsters that destroy is best offset with some real truth that such people like to ignore or erase. A vision and perspective that heals and bridges above all else.

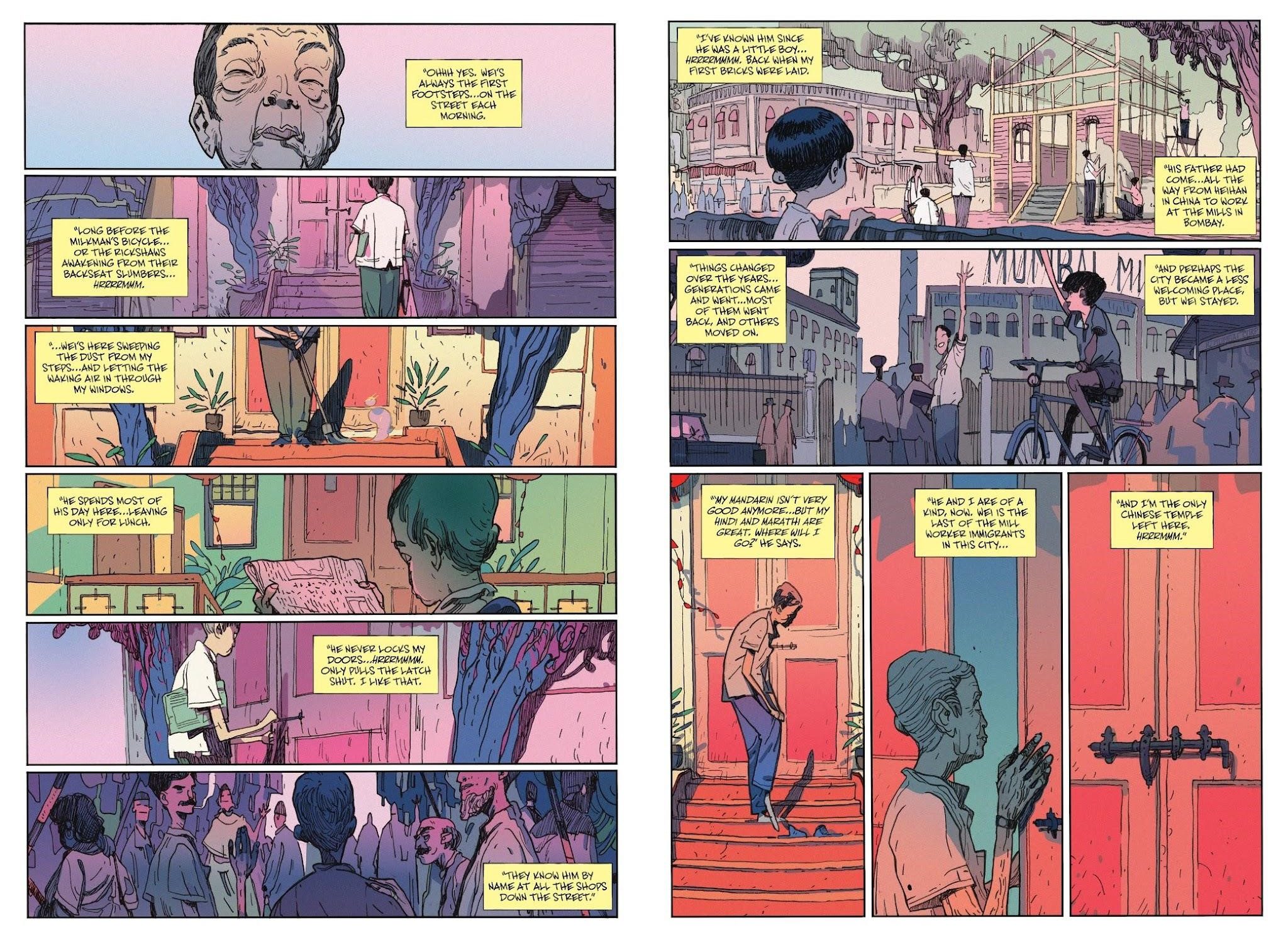

And so in an issue set in Darius’ 30s, with him as a widower with a son, we deal with the ordeal of a life full of burdens that threaten to shatter us. We explore the life of Wei, a Chinese-Indian immigrant, who’s lived in Mumbai all his life, past any peers who are now long gone. The book brings up the oft-ignored, overlooked presence and history of Chinese Indians in the nation, who often don’t fit into its own assumed identity. They don’t easily fit what many think when they think ‘India’, but theirs is a reality you cannot erase. The Chinese-Indian communities may now be a fraction of what they once were in size, particularly after the 1962 Sino-Indian War, but they still exist, as do entire generations who have only known India. Wei is a symbol of that, being the son of Chinese worker immigrants, now standing as the custodian of the last remaining Chinese Temple in Mumbai. And it’s perhaps here that Laila Starr it at its most evident as a work about endurance.

Look at what they don’t teach you; look at what they don’t tell you; look at the truths you may not know. Understand, the work seems to say.

India and ‘being Indian’ have always meant rich diversity, whether it’s ethnic, cultural, or religious. The definitions you know and the ideas you may hold are narrow, far too narrow, for this is a place far bigger, far richer, and more wonderfully varied, the work seems to want to remind the reader.

It’s a truth that brings joy to the soul, that reminds you of how connected people have always been, and always will be, and how in the face of nationalistic attempts to rewrite the history and the past, there are beautiful things that can never be forgotten. That falsehoods cannot compare to the genuine grace and majesty of the truth of the lives that have been led on these lands. Their lies live on, but so do the people who defy and disprove them. And that’s life.

The chapter's primary concern is about the demise of places and how places are defined by people, but at the same time this grants the work a whole extra layer of joyous spirit.

And by the end of the book, in chapter five, after what feels like a whole cultural criticism and thesis has played out just in the background of the work, the book brings us to another Indian specificity to conclude things, after a whole series full of them, whether people notice or not.

We approach a common fantasy and idea of many: the Goan Retirement.

Goa, the once Portuguese-occupied territory of the nation, is a popular tourist spot and also a lovely place many say they’d like to live when they’re old and ready to retire. And it’s where Darius ends up, except the fantasy isn’t so romantic or pretty as it usually sounds. He’s alone, with no one, like a mad scientist, surrounded by a swarm of injured or struggling animals he’s rescued.

Darius is now an old man full of regrets, left with nothing, whose own son wants little to do with him given Darius’ own poor treatment and inability to give the boy time. And Darius is now dying, with very little time left. All he does now is fix up broken animals and creatures on the verge of dying, with little else to do.

It seems bleak. This is not the happy Indian fantasy people like to conjure up at all. It’s more like an Indian nightmare. This is a man who lost the love of his life in his 30s and has since spent his life alone. It feels like a tragedy, and while reading it I’m reminded of something striking. We’ve already discussed South Indian film context and influence above, but it becomes vital here once again. Perhaps more than the Yama stories, more than the Avatar myth influences, maybe the most strikingly obvious and potent baked-in influence here structurally upon Laila Starr as a series might just be Mani Ratnam’s Tamil-language gangster epic Nayakan (1987), starring the legendary Kamal Hassan. Built around an entire lifetime of a boy named Velu, it spans his youth as the son of a union leader who’s murdered by the cops, who then kills his father’s murderers and runs off to Mumbai, to his rise as a gangster, and his eventual fall from prominence and demise as an old man. It is many things, but above all else, a tragedy. And that sense of ‘an entire lifetime encapsulated across sections in one large story’ comes across strongly through a work like Laila Starr.

Darius’ position is dire and even Laila Starr, Death herself, finds it so when he arrives to finally meet him at the end of his life. She confesses that she’s attempted to kill Darius through various stages of life, but she could not find it in her to do so.

And that’s when there is a smile, a grin, a liveliness, leading us to learn that Darius did actually invent a way to do away with dying. He found the secret of immortality on the eve of his 50th birthday. He’d done it, as the gods foretold he would.

And then he took it and put it in a shoebox (which reads VATA, a nod to iconic Indian shoe store BATA), and never looked at it again.

Thus we come to the most striking and powerful sequence in the entire book. Darius lays out how his was a foolish endeavor, and how to act upon it would have only been even more so.

And so the two characters find themselves in a sort of strange stalemate. Laila Starr, having every chance to pursue her desired path, and Darius Shah, having every chance to pursue his desired path. They could both ‘win’. But neither of them wants to. That’s not their desire. This is not the story of a genius mortal playing trickster with Death to get some happily ever after. If anything, the very possibility of a ‘happily ever after’ like in those Yama tales died with Darius’ wife. This is also not the tale of a demon or pesky monster like in an Avatar story. And Laila Starr is not Yama, nor is she the Avatar, who tends to always get his man. Laila lets go of her man, the person she’d intended to slay all this time.

What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object?

They surrender.

This is not a Yama story. This is not an Avatar story. This is a Laila Starr story. This is new. This is something different.

It’s why Laila and Darius sit down at the beach together and relax.

The story subverts and rejects all the expectations of the myths and tales it invokes and draws on, to forge its own conclusion, and what we get isn’t tragic at all. It’s not dire or heartbreaking. It’s delightful. Unlike all those men obsessed with immortality in those Avatar tales or the tricky mortals cheating Death in Yama tales, Darius is neither. He doesn’t want to live forever, and he doesn’t want a happily ever after. He understands a wisdom none of the people in those stories seemed to:

He’s content with what he’s got, he’s happy with whatever limited time he’s granted. He isn’t driven by the need to attain one extra second more. Living in itself is enough for him. He’s content. It doesn’t mean all the mistakes, errors and regrets go away, god no. It doesn’t mean guaranteed happiness. But it does mean acceptance. It means an inner peace and balance. It means relishing existence in a way that is otherwise hard to do. It means truly living: living with Death, laughing, not running away.

It’s a strikingly different story and outcome from Gaiman’s vision of Death, wherein we saw a fully-formed kind and compassionate psychopomp from the jump. Gaiman’s was a Western vision of Death that knew exactly who she was, how she had to act. She was a universal abstract, an immortal idea, yes, but she was also at once deeply human and caring and considerate. Perhaps she maybe needed a day or two in human form every now and then to keep her in touch, but largely, Death just was the way she was. She just was that way because that fits into Gaiman’s cosmology: that the universe may be unfair, and harsh, and wrong, but it is also understanding, caring, gentle, and compassionate, when it comes down to it.

Ram V and his collaborators’ Laila Starr is not quite that. She is cold, harsh, alien, set and determined to murder a child just because, with not a sense of doubt or a moment’s hesitation. Even after she emerges onto the earth, she clings to that ideology and vision, the cold vision of Death, as she boasts of her might and power and how she’s taken the lives of legions, that this all means nothing to her.

And that’s true, because she’s an Idea.

Abstract ideas, ideas on their own, divorced from humanity, become monstrous - this is what Ram’s work and vision seem to argue. Death as abstract cannot automatically just be human, compassionate or kind. She’s just an idea, a force of existence. She just is. And she can’t be truly understanding and loving even after a day or two, or even a week in human form. No, it takes a lifetime. Death as an idea can never automatically be what Gaiman’s Death naturally manifests as. To become anything like that, to become a Death resembling compassion, understanding, kindness and gentleness? It takes ages, it takes her being human and experiencing life in various ways again and again, to really get it. It’s one thing to know and be nice about it. It’s another to have lived it and to understand the experience and thus embrace another being in that shared knowing. It takes time, and it’s an arc.

Laila Starr is the long journey that it takes for a force of the universe, an universal abstract like Death itself, to become humane, in the way that a writer like Gaiman once imagined it could be.

And it’s a journey only possible given that Death herself starts out afraid, fearful of her own survival and endurance - for if Death is eradicated, who is she to be? Just another mortal, in a stinking, frail mortal body; no longer a god, but an immortal human who can never escape the coils of life. There’s a vulnerability and a sense of self-preservation that emerge in Laila from her early human days, which by the end morph into a much more fully fleshed-out humanity that meaningfully defines her.

Only once Death’s own conceptual demise is nearby, is she fully able to embrace her humanity and mortality, which is a fascinating touch. Death must live, for if we are to live with Death ourselves, so must she, no?

It’s a recurring motif in Ram V’s work, as you repeatedly see a fascination with immortal ideas/concepts/myths bound to mortal existences. The idea shapes the mortal, yes, but the mortal shapes the idea just as much. It’s an interest that can be traced back to Gaiman’s work as well, as the British writer put it eloquently in his own opus The Sandman, in the words of Dream:

Without the mortality, the actual humanity, the idea becomes monstrous. It is the tether and experience of humanity that makes it matter, that makes it meaningful. Meaning derives from the observer, from the people that project it onto a cold void of cosmic reactions we call the universe. It’s visible in These Savage Shores and its Raakshas, it’s the heart of Ram’s revival of The Swamp Thing (DC, 2021-22), and you’ll even find it in his Aquaman: Andromeda (DC, 2022), which explores him as the mythic Avatar of the oceans. But it’s also there in musical noirs like Blue in Green (Image, 2020), wherein an artist must give up his humanity to become Great. He must become an idea of himself, the Great Musician, a mythic version of himself, but the price for that is all his human connections, and the mortal life he would otherwise have liked to lead with the woman he loves.

Mortals and their ideas, ideas and their mortals - their dance fascinates Ram V, evidently. And that dance takes place here, once again, in stirring, powerful fashion with Death itself.

For life is meant to be lived that way, not in a haunting fear of Death, but in calming acceptance of it. You don’t run from Death. You walk alongside it. It is our constant companion, and it is because of that that it helps contextualize our lives. It is because our lives end, it is because our time here is limited, it is because we only have so many choices, that we are who we are. Life and Death, these things don’t have meaning on their own, by themselves. Theirs is a meaning that derives from their co-existence, their symbiotic nature and harmony.

The dance with Death is what defines all of our lives. It is what our existence is.

Mrthyu. Maranam. Savu. Maut.

We certainly have a lot of words for Death.

But we have just as many for life, too.

Jivanam. Jivitam. Vāḻkkai. Zindagi.