So let’s talk a little bit about Crisis on Infinite Earths!

In the first place I should probably say that when I was younger and getting sporadically published in The Journal during roughly the last quarter of its initial print incarnation – a healthy run by any stretch as a semi-regular contributor – I never imagined I would be published one day in those same pages (albeit virtual), singing the praises of Crisis on Infinite Earths! I thought for sure and for certain I’d spend the rest of my life publishing sober analyses of all the latest impenetrably minimalist monographs produced by extraordinarily talented but also minutely obsessive middle-aged craftsmen with the time, resources, and patience available to design a single book to within three tenths of a micron of its life. But alas.

(Could probably have done a lot more at the time had I not flamed out and almost completely destroyed my life during roughly that same period. My [old] name was on the masthead for a year or two after I was foolhardy enough to accept the position of webcomics columnists. I needed the money. I couldn’t find an angle that made the subject open up – I admit, I was a bit more ambitious about what my workload would be in the year leading up to my divorce when I didn’t know it was the year leading up to my divorce. Hey, it’s been a really wild ride, let me tell you! I mean seriously, let me tell you.)

Crisis on Infinite Earths is a book that many people have read, many more people have discussed, but apparently few people have ever actually enjoyed. I’ve seen younger fans approach the idea of reading Crisis for the first time as if it were some sort of chore or obligatory duty – yeah, yeah, if I like DC comics or want to understand Final Crisis or maybe just check another one off the proverbial “1001 Comics To Read Before You Die,” I have to at some point wade through this monster. And I have never understood that attitude, I find it completely alien. Incomprehensible!

Let’s stop for a moment and talk about what that means and doesn’t mean: I’m not here to make an argument about whether or not Crisis of Infinite Earths belongs in the great canon of western comics literature. That’s a boring, incredibly awful and pedantic argument to have, I mean, if you really care we can go back in time right now and slip Crisis back into the running order of the Journal’s old “100 Best Comics of the Century” list right where it should have been all this time, at #672, right behind Will Eisner’s strips for P.S. The Preventative Maintenance Monthly.

I suppose the question is interesting as much for my sake as a writer as for yours as a reader: why did I like Crisis so much all those years ago? I loved that comic. Still do. Not just the parts that most people still do seem to enjoy – the death scenes, specifically those of Supergirl in Crisis #7 and the Barry Allen Flash in #8 – I loved the weird parts where the Monitor is talking to people and you just get to see random assholes wandering off panel during an infodump, or you get a one panel cut-in so some schmuck who appeared in an issue of First Issue Special in 1976 can wave to the crowd, “Hey kids, remember me? No? God fucking dammit.” It’s the kind of book where multiple rereadings are necessary to bring little details into relief, because it’s the kind of book that’s built on nothing but details, a sea of details, an ocean of exacting George Perez details. There’s no way to actually read the book for the first time because it’s impossible to understand anything in the book until you understand the plot backwards and forwards.

I suppose the question is interesting as much for my sake as a writer as for yours as a reader: why did I like Crisis so much all those years ago? I loved that comic. Still do. Not just the parts that most people still do seem to enjoy – the death scenes, specifically those of Supergirl in Crisis #7 and the Barry Allen Flash in #8 – I loved the weird parts where the Monitor is talking to people and you just get to see random assholes wandering off panel during an infodump, or you get a one panel cut-in so some schmuck who appeared in an issue of First Issue Special in 1976 can wave to the crowd, “Hey kids, remember me? No? God fucking dammit.” It’s the kind of book where multiple rereadings are necessary to bring little details into relief, because it’s the kind of book that’s built on nothing but details, a sea of details, an ocean of exacting George Perez details. There’s no way to actually read the book for the first time because it’s impossible to understand anything in the book until you understand the plot backwards and forwards.

It’s the kind of book where absolutely everything in the plot makes so much sense that nothing makes sense, if that makes sense.

(Probably while I’m on the subject I should mention that there was one exception to the general malaise I was feeling about my comics reading in the mid-00s: Fort Thunder. If you’ve never heard of them that was the name of a warehouse in Providence, Rhode Island that served as a living and working space from 1995 through 2001 and oh my goodness, that was already twenty-three years ago. The Fort had already been torn down to build a parking lot [true story] by the time I first heard about them in 2003 in The Comics Journal #256. Over the next few years I tracked down whatever I could from every artist profiled in that issue . . . which was not as hard as it sounds, seeing that most of them appear to treat comics as a side gig, which, well. The only artist from whom I’ve collected multiple prints – from whom I’ve collected any prints, actually, because I’ve never had the space or set-up or money to collect artwork – is still Mat Brinkman. I’d hang them in my house if I could afford the frames. Completely unique talent.)

I loved Crisis even though I wasn’t really paying attention to DC at the time. My comics reading at that period was limited by two guiding beliefs. The first guiding belief was that Marvel’s Transformers comic was terrible – a belief that was not at all affected in one bit by the fact that it was also my favorite comic. That’s a very interesting lesson to learn as a small child, your favorite thing is kind of terrible! Because I was a kid I had no problem with the fact that these two ideas can exist independently as both completely and absolutely true and also of no great consequence to each other. I liked the Transformers comic because it had the Transformers in it, that’s about as simple as it got.

My second guiding belief was that Carl Barks was the greatest cartoonist who ever lived, an opinion which I adopted pretty much the moment I discovered Gladstone’s line of Disney reprints in the mid-80s and have never shaken for a single day in all the ensuing years, sorry Jack and Charles and R. and whomever else is not as good as Carl.

But a bit later when I decided superheroes weren’t awful (an opinion I held at a young age simply because I was a child and didn’t understand that superheroes were Serious Business For Serious People, which, I mean, what can I say. I was a kid, I probably also thought manmade climate change was real) I went back and discovered the book after I decided that comics like Crisis were my favorite kind of comics. And this came as a bit of a surprise because my favorite kind of comics were actually no kind of comic at all but the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe, which captured my imagination in every format except for the loose-leaf binder pages. (Which I nonetheless bought because your favorite thing is kind of terrible!)

DC didn’t have an Official Handbook, what they had was Who’s Who. That was a swing and a miss for many fans in its first incarnation partly because it purposefully avoided what made the OHOTMU so compelling – it’s pretense at precision and objectivity in its catalog of the fantastic and made up. The OHOTMU was a definite and formidable aesthetic in its own right, all the more so because it’s aesthetic was garbed in the facelessness of authority. This was official. It said so in the title! It looks kind of like a government document, what fun!

DC didn’t have an Official Handbook, what they had was Who’s Who. That was a swing and a miss for many fans in its first incarnation partly because it purposefully avoided what made the OHOTMU so compelling – it’s pretense at precision and objectivity in its catalog of the fantastic and made up. The OHOTMU was a definite and formidable aesthetic in its own right, all the more so because it’s aesthetic was garbed in the facelessness of authority. This was official. It said so in the title! It looks kind of like a government document, what fun!

Crisis in Infinite Earths began at the same period as the genesis for Who’s Who, and came from the same people – Marv Wolfman wrote Crisis as well as parts of Who’s Who, alongside Len Wein. Perez provided the covers for Who’s Who as well as everything for Crisis. It was designed to streamline DC’s massive continuity, but perhaps just as importantly it was designed as a celebration of DC’s massive continuity. And perhaps if the idea of “continuity” seems like a terrible thing on the face of it, an odd thing to celebrate, or at least alien and superfluous to the values that you enjoy in comics, think about it this way: continuity itself is really quite imaginary, too. It’s all various ways of dressing up and making sense of things that are not real.

You can choose to look at that like it’s drowning everything, squeezing all the life out of its lungs. I see that, as well as the argument that this kind of obsessive minutia acts as a huge obstacle. There’s no doubt that it does in many instances, and there’s just as little doubt that it’s used as a cudgel by those on the perceived “inside” of a fandom to keep out those whose knowledge is incomplete and, therefore, unclean. You know, the kind of asshole who can’t even begin to take seriously any opinion you have on the subject of comic books until you prove that you have read every comic book.

Spoiler warning: those people can never be satisfied. I suspect they are also quite dissatisfied with themselves, but that’s just between you and me.

Open your eyes and look around you: Everyone loves continuity. Everyone’s a fan of something, these days. People like remembering things and obsessing over things and geeking out over who that guy is in the back of that one episode of Game of Thrones, what’s his name when did he show up before . . . half of everyone you know plays D&D casually and the whole point of that game is to be able to look at a piece of paper with disembodied stats and figures and see infinite storytelling possibility. It works because people like stories, not because people like dice and numbers (please don’t burn me in the comments, I know people love dice and numbers too). Game of Thrones doesn’t have an Official Handbook but it has an atlas sourcebook thing, which my mom keeps next to her bed in case she’s lying awake at night and needs to know the capital of Dorne. (It’s Sunspear. I had to look it up, don’t worry.)

What else are the OHOTMU – and Who’s Who, obviously, if we can look past the question of aesthetics – but just different ways of organizing and therefore playing with stories? Some people like to break them into little itty bitty cubes, at which point you can then piece them back together in random interesting formulations for the rest of eternity.

The most compelling explanation I can offer as to why I like Crisis is that it’s a series that manifestly did not need to exist, and yet it does. And the reason it exists despite the fact that it was nothing but a massive complication in the lives of every single person involved in its creation is that they really wanted to make it. Marv Wolfman and George Perez willingly signed up to produce one of the most brutally labor-intensive projects in comic book history simply because they wanted it done right. You would never, ever sign up to make Crisis – certainly never pitch Crisis in the first place – unless you were sure, deep down in the pit of your soul, that it was something you really wanted to do.

The most compelling explanation I can offer as to why I like Crisis is that it’s a series that manifestly did not need to exist, and yet it does. And the reason it exists despite the fact that it was nothing but a massive complication in the lives of every single person involved in its creation is that they really wanted to make it. Marv Wolfman and George Perez willingly signed up to produce one of the most brutally labor-intensive projects in comic book history simply because they wanted it done right. You would never, ever sign up to make Crisis – certainly never pitch Crisis in the first place – unless you were sure, deep down in the pit of your soul, that it was something you really wanted to do.

Why is that such an important point? People take Crisis for granted because it’s important. It’s a dividing line. There’s pre- and post-Crisis – you don’t need to specify which Crisis. But think about just how much easier every single person at DC would have had it in the 80s if, when Wolfman pitched the concept of the series, the company had accepted the suggestion but not the pitch? That’s essentially what they did later with the New 52: they announced an end date for every series, wrapped things up rather abruptly, and started all over again literally from scratch. Except for the series that picked up where they left off because they were already selling well and there’s no way that’ll create problems except and oh god they made all the same mistakes. Hey, I know how to fix it – moar Watchmen!

There’s no reason why DC editorial in the early 1980s couldn’t have just said – you know, maybe things do need to be streamlined, but the solution you’re proposing, what is this, Crisis? You mean like the JLA/JSA team-ups? Nah, seems like a lot of work. But I think the streamlining is necessary. The problem with a big crossover is that it’ll step all over where the attention should be: the creators getting to wrap up the stories in their books before an arbitrary end date of, say, June 1986, and the new guys taking over right after. Everything ends cleanly, then everything starts up cleanly with brand new #1s in July. Except for Action & Detective, we’ll keep the numbering there because there’s no way we’d ever be foolish enough to mess with our two flagships. Why, that’s crazy talk!

For some reason I will never understand DC chose to do Crisis. And I love it because it’s weird and intense and completely hermetic in its pleasures, and the kind of comic that really can’t be anything else but a comic book. It’s not a comic that I love despite all the little details, it’s a comic I love because all the little details. It’s a passion project of a very specific type of passion, an incredible effort that could only have been the fruit of years and years of monkish devotion and research on the part of every single person involved. When I came along after the fact to piece together a run of Crisis and all its important crossovers from quarter boxes across the West Coast I wasn’t fascinated because as a kid I magically knew all the continuity bullshit, or even a small part of it. I was fascinated because I recognized the exigence here. It wasn’t to streamline continuity. It was to read and obsess over a pile of comic books.

Crisis was made so that the men who made Crisis could experience the pleasure of making Crisis, and then show off having made Crisis. Same as the real point of making OHOTMU for the men who made it was undoubtedly getting an excuse to read all those wonderful, terrible comics again and bitch about them with their friends at the office. Mark Gruenwald almost certainly had more fun making that book with his collaborators than anyone had reading it, even those who loved it. George Perez, bless his heart, loves drawing all those tiny little dudes standing in the corner. And that’s a wonderful thing.

Even though Crisis is a very heavy story (worlds live and worlds die, y’know) it’s still a celebration. A peculiar kind of celebration, but one designed to appeal to a certain peculiar kind of fan – and dear reader, I was that fan.

II.

The reason why Fort Thunder appealed to me so strongly in a period of my life when I really wasn’t connecting to much else in comics is that there was a passion and willingness to be weird that seemed free of the increasingly suffocating sterility that jumped out as the important movement from the previous decade of “serious” comics. There’s a lot of good and important comics – a few of the greatest comics ever made, even – that emerge from that essentially defensive place, aesthetically speaking. Comics were still disreputable, after all. In order to be taken seriously as art comics needed to be good, and good comics had to be serious comics, and serious comics tended to be intimidating, impenetrably minimalist monographs produced by extraordinarily talented but also minutely obsessive middle-aged craftsmen. Which was only natural, after all, these were the same kind of virtues that tended to attract critical approbation in other genres at the time.

Sometime in the 00's there was a seismic shift in the writing about comics as the generation who had fought hard for decades to pull comics out of the ghetto of kids stuff and licensed adventure books, to get graphic literature reviewed in the right papers and stocked on the right shelves at Borders, turned around just in time to see the next generation come up lionizing G.I. Joe #21 as a milestone book. Fort Thunder was a forerunner for that movement, a delayed lightning bolt that arrived in our hearts somewhere alongside the advent of Kramers Ergot as the most important anthology of the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Their collected oeuvre went off like a delayed time bomb in my brain when I found them. They didn’t do minutely observed depictions of aching ennui and angst, they did weird things like draw stick figures fighting over 350 pages of a Japanese book catalog. Why? There’s no context, there’s no point where it makes sense as something that represents a recognizable view of the world. It’s noise and movement and life and the absolute final word on the subject of comic books as art objects: you can only design something so completely and thoroughly before you realize it’s all just obsessive scribbling. Why do you do it? Because it’s fun and cool why the fuckety hump not?

I mean, it’s not like you were you using comics as some roundabout scheme to get backhanded compliments from the (sclerotic and teetering) American literary establishment, were you?

I dropped out of grad school last year. Saying “I left of my own volition peacefully after completing the requirements necessary for a terminal masters degree” doesn’t have the same ring to it even if it’s more accurate. I consider myself a dropout partly to register my disgust for the whole enterprise. And that’s nothing against the people there or even the act of literary criticism at all, even the really cramped stuff with all the footnotes. I think it’s very important, even the stuff that isn’t important at all. It’s difficult writing. I know how to do it enough to know how to do it moderately well, but I’m absolutely certain every single teacher who worked with me could tell I was stymied by the form.

My disgust stemmed from my own vexatious nature. I’m disgusted with myself for not feeling like I can hack it, but in my defense I’ve had a weird few years. But I’m also disgusted with myself for feeling like I needed to have that kind of authority. Honestly, I say I have a Masters but I need to finish the paperwork, one last bit of which remains to be done and I can’t even bring myself to do it. The idea that I used to think it would fill some kind of hole inside of me to have a few more letters after my name – just highlights how big a hole I had.

But I learned a lot, lessons of both of the intentional and unintentional variety. I learned about different kinds of styles of reading – paranoid and reparative reading, courtesy Eve Kosofky Sedgwick. I encountered that distinction my first year in grad school and I don’t think I encountered a more powerful idea in terms of my own understanding of the purpose of critical writing. The problem is that this idea of reading reparatively was presented as the context merely of being another idea in the panoply of academic ideas open for our consideration as budding scholars. It struck me as problematic inasmuch as if you took it seriously, it rather argued against much else of what we were doing.

Academia is a paranoid field. Many of the tools in the critical toolbox are built on the presumption of a de facto adversarial relationship between the reader and the text. It’s never about what the text actually says, it’s about what the text says when it isn’t trying to say anything at all. All very Freudian (especially if they hate Freud). When it works well it places the critic in the position of uncovering hidden truths or accumulating unseen connections between seemingly disparate but in fact related phenomena. When it works it can do wonderful things, can open up new ways to understand very complicated ideas.

It’s the critic in the role of private investigator, sifting through the effects of a work of art like picking the pockets of the recently deceased. I could never find a question, in that context, enough to interest me more than I was interested in the texts themselves. I don’t think I ever really figured out how it was all supposed to go. But throughout this period where I strained mightily to learn how to rip and tear texts to shreds I would go home and spend hours watching cartoons or sitcoms or Star Wars – lots of fucking Star Wars, believe me – trying to numb myself out of feeling the worst of the severe depression that hung over me throughout the entirety of my time there. And I couldn’t read anymore, because reading was work, reading was looking at books like a vampire looks at a discotheque, constantly thinking, am I gonna be able to find enough quotes to fill my bibliography so it doesn’t look like I read more than one book because I promise you I only plan on reading one book?

The only stuff in my life I still enjoyed was stuff that I purposely and actively excluded from study. I think that was a necessary defensive move. Why didn’t I write a dissertation on Star Wars? There would have been absolutely nothing stopping me from writing a dissertation about Star Wars. I probably could have written a good one. But it honestly didn’t occur to me, and I think the reason why is that I wanted to still be able to enjoy watching Star Wars once I left graduate school, whereas reading books for me now is so far kind of becoming a PTSD thing which only sounds like a joke if you’ve never dropped out of graduate school.

I had to go to graduate school for six years to figure out that there’s no moral component to the act of reading. You can read Middlemarch or you can read The Turner Diaries, both acts require precisely the same fine motor skills. What matters is how you learn to think, and you can do that with or without books or formal education. I mean, yeah, I can sit here and tell you that it doesn’t fucking matter how many books you’ve read, I mean, I’ve read Moby Dick twice and only one of those times was for work. I acknowledge that it’s an argument from a place of privilege. But I feel like I had to actually achieve that privileged position to convince myself that it didn’t matter to me, if that makes sense. It didn’t surprise me when it felt hollow, but it did mean I’d ruined my ability to read books for pleasure for not a whole lot in return. Actually kind of ruined my life to learn that lesson. Surprise, your favorite thing is kind of terrible!

I had to go to graduate school for six years to figure out that there’s no moral component to the act of reading. You can read Middlemarch or you can read The Turner Diaries, both acts require precisely the same fine motor skills. What matters is how you learn to think, and you can do that with or without books or formal education. I mean, yeah, I can sit here and tell you that it doesn’t fucking matter how many books you’ve read, I mean, I’ve read Moby Dick twice and only one of those times was for work. I acknowledge that it’s an argument from a place of privilege. But I feel like I had to actually achieve that privileged position to convince myself that it didn’t matter to me, if that makes sense. It didn’t surprise me when it felt hollow, but it did mean I’d ruined my ability to read books for pleasure for not a whole lot in return. Actually kind of ruined my life to learn that lesson. Surprise, your favorite thing is kind of terrible!

So what does any of that mean? It means going back and looking at something like Crisis on Infinite Earths is really kind of a pointless exercise if you’re just going to bash it over the head again with a guitar like some kind of obsolete cartoon horse. Because it seriously, and I completely promise you, matters not one bit whether or not Crisis on Infinite Earths will ever land anywhere near the great canon of western comics literature. The book matters a lot to me because I recognized at an early age that a book like that could only come from a place of deep love. There is simply no other word for the kind of devotion. And there is no rational explanation for the existence of this book other than that these kinds of stories and projects are how nerds build monuments to great achievements in the fields of nerddom. And that’s a wonderful thing.

That’s also why I’ve been waiting a long time to draw a line between George Perez and Brian Chippendale. Because there’s a similar energy. There’s a similar approach to composition based around trying to draw a bunch of cool things all at once and worrying about how it’s going to fit after the fact. This isn’t the kind of work that you produce because you’re anxious about whether or not what you’re doing is going to be perceived as Serious Personal Expression. It’s what you produce when you just want to sit down and express something really cool.

III

So of course they pulled a sequel out of their asses less than a decade later.

Zero Hour was a story that existed for the sake of crossovers and spinoffs. It was a weekly book – weekly! – five issues dedicated to remaking the whole DC Universe. What that meant in practice was five issues filled with a lot of white space, which meant a whole lot of panels without backgrounds. There’s a bad energy to the book. It doesn’t feel like a story that anyone involved wanted to tell for the simple reason that no one seems to enjoy any part of telling it. Literally the only part of the series that appears to engage the creative team on any level is the periodic shots of super-heroines looking pedantically sexy. Put Throwing Copper on the Discman and relive the nineties with me, baby.

There’s an art to crossovers and the key ingredient is enthusiasm. It seems like a really basic thing to say, considering how often we’re used to judging corporate comics on a very generous scale. If we’re considering the aesthetics of crossovers in and of themselves – something I know not a lot of people really want to do, but if you’ve held on for this long we can certainly go a bit further – most people really despise them. People read them because you have to read them. But people generally really resent being frogmarched through a joyless recitation of, “Hey, here’s my new best friend DAMAGE, he’s going to be really important for the future beginning next month and hopefully for many subsequent months afterwards. I mean, it would be terrible if this sequel to a very important comic book in the history of DC Comics depended on a character who disappears more or less when his very weird series ironically implodes just a couple years later . . .”

. . . and wait a minute, you realize, coming up for breath, Damage still lasted twenty-one issues, running from April of 1994 to January of 1996 and including one #0 issue the month after Zero Hour. And that was a failure. In the 1990's even in the middle of a serious and sustained period of industry contraction, Damage still ran for over a year and a half. And it was a failure. WHAT PART OF THIS IS A DYING INDUSTRY DON’T YOU UNDERSTAND I MEAN.

So they pull the trigger on the formal sequel to one of the most important stories in the company’s history and the result is – well. It’s a series that existed to enable a handful of clever crossovers. The series with the oldest characters – the Batman and Superman titles and families – were able to capitalize on the various series’ very long histories and produce some fun one-offs. It may seem very quaint now but the idea of actually putting pre-and post-Crisis versions of characters together formally was a really fucking big deal. Big enough for them to premise an entire crossover on the fact in the mid-90's.

So they pull the trigger on the formal sequel to one of the most important stories in the company’s history and the result is – well. It’s a series that existed to enable a handful of clever crossovers. The series with the oldest characters – the Batman and Superman titles and families – were able to capitalize on the various series’ very long histories and produce some fun one-offs. It may seem very quaint now but the idea of actually putting pre-and post-Crisis versions of characters together formally was a really fucking big deal. Big enough for them to premise an entire crossover on the fact in the mid-90's.

And I was a lonely kid, an easy mark for a crossover that peddled in cheap nostalgia. I liked Crisis enough, and held enough fondness for that kind of story, that I convinced myself that its sequel wasn’t terrible even though it looks like every single person involved in the making of this comic book probably now wishes they weren’t. And do not fucking get me wrong: I loved this comic. I bought every single fucking issue and every single fucking crossover off the stands and I read those sons of bitches backwards and forwards even though by then I was really getting way too old to fool myself into believing that I was still getting anything out of huffing someone else’s madeleine farts.

The weird thing about comics, though, is that nostalgic events usually (not always, but usually) have one under-discussed ace-in-the-hole: creators sometimes get excited for nostalgic themes in ways that they don’t for any old random kind of crossover bullshit. It’s probably really nice to write something with those themes if you’re trapped in the middle of the usual death blood whatever bullshit monthly grind, oh hell, I get to write about Xeen Arrow for a month WEEEEEEEE.

(OK, I don’t think anyone’s actually done a nostalgia showcase about Xeen Arrow but I am totally volunteering to do that right here. I will outline twelve fucking monthly issues that will change everything you have ever believed about the Xeen Arrow. With Mopee as my witness it’ll make Camelot 3000 look like Spanner’s Galaxy. DC, you know how to find me. It’s what the kids want.)

But I loved crossovers, you see. It’s a dirty shame that I don’t actually do a very good job hiding. I fucking love the hideous things. Even the terrible ones. Especially the terrible ones. I own the hardcover of Civil War because even though I loathe that story it’s still a good crossover, a paradox I have never been able to unravel. How can I possibly love such hideous and awful things? What is there to love?

Good crossovers have been put together by people with an actual desire to tell a really, really big story using all the toys at once. Good crossovers have massive moments that you carry with you longer than you think because the size of the story did a lot of work to sell the scale. I mean, you know that bit where Captain America stands up to Thanos is from a crossover, right? This is one of the most iconic Captain America moments ever, manufactured in a couple pages – a complete throwaway, other than it being a really good moment – of an otherwise massively cosmic story that has everyone from Wolverine to Nebula to ALF. (LOOK AGAIN HE IS THERE I PROMISE YOU.)

Good crossovers have been put together by people with an actual desire to tell a really, really big story using all the toys at once. Good crossovers have massive moments that you carry with you longer than you think because the size of the story did a lot of work to sell the scale. I mean, you know that bit where Captain America stands up to Thanos is from a crossover, right? This is one of the most iconic Captain America moments ever, manufactured in a couple pages – a complete throwaway, other than it being a really good moment – of an otherwise massively cosmic story that has everyone from Wolverine to Nebula to ALF. (LOOK AGAIN HE IS THERE I PROMISE YOU.)

And that’s cool. That’s something I recognized immediately, I mean, absolutely from the get-go, as being the definition of inside baseball. The more you learned about all the history the more everything meant. Because characters are like people. They carry history. That history means something, communicates character.

That’s what I loved. It didn’t exclude me. I mean – look. I had a rough childhood in some parts. It was OK in some others. But I was bookish and living up in the mountains meant that I never really had any other kids in the neighborhoods where I lived. Everything was very diffuse. So I spent a lot of time putting this shit together in my head based on what little resources I had. Pre-internet. You learn to read a lot from inference and to savor the recap passages whenever they occur. And whenever any issue numbers recur put them on a shopping list for the next trip to town.

It’s a familiar story. Maybe you’ve got some variant in your past. It’s not really a sad story unless you choose to look at it that way. It certainly wasn’t misfortune that left me exiled from other kids, I just didn’t live in the right neighborhood. I actually did have some very beautiful scenery, which isn’t nothing, if not quite the same as having enough kids around to play a game of pick-up. So I watched a lot of TV, ran around outside with my dog, and read the same comics over and over again. Part of the value of the experience of reading comics was the density imparted by having to pore over and exegete a dragon’s horde of contextless minutia from a world before my birth. Kills a lot of time.

I suspect a lot of kids who have lonely childhoods get over it by growing up and creating things that can really only be appreciated by kids with similarly lonely childhoods. I don’t know. Maybe it’s just me. But that kind of willful and enthusiastic attention to detail – not the cramped and precise detail of a monograph, or the cramped and exhaustive detail of an academic essay, but the frenetic, devoted, absolutely, positively, madly committed detail that is the sole province of the truly smitten . . . it’s cramped because his hand is sore from drawing all day, or because there’s just too much shit that needs to go in this panel because boy fucking howdy is this a big story, boys and girls let me tell you!

Crossovers are stories that only fans can tell because they’re only for fans. If they aren’t always just objects of absolute and total commercial calculation – and do not doubt me in any way, they are also always that as well – they can also be artifacts of enthusiasm. The proof here is one of the best crossovers of all time: DC One Million, written and spearheaded by none other than Grant Morrison. DC One Million was a story told in the exact same format as Zero Hour: a weekly mini series into which every book in the main line crossed over for that month. The difference in execution between Morrison’s book in 1998 and Zero Hour in 1994 is that Morrison looked at the idea of having literally the entire month of a major comic book publisher at his disposal as an opportunity to think of the biggest fucking story he’d ever be able to tell in his entire life, and the people who made Zero Hero – Dan Jurgens and Jerry Ordway – really struggle to make it apparent what is happening at any given time on the page. Honestly, rereading Zero Hour after all these years without the context of any of the crossovers is completely bewildering. The only thing that the absence of context makes clear is how little, in a vacuum, anything in the comic matters.

Because of the lead time and precision necessary to create Crisis it mostly avoids the pitfall a lot of the more cynical crossovers do of simply serving as a showcase for whatever books are getting a big push coming out of the seasonal catalo– er, crossover, sorry. The point of Crisis was that everyone was getting a walk-on, whether the company was just then trying to push them or whether they had appeared in one issue of Showcase when Dwight David Eisenhower was doing his part in the grand historical effort to keep the Oval Office tidy in fevered prophetic anticipation of its current occupant. Because literally the entire comic was a form of hardcore fan service it could actually think about how to tell a story that was composed of nothing but fan service.

When you put it that way it’s remarkable that Marvel has somehow figured out how to bottle and sell even just a whiff of that real and genuine monkish fan high of a good crossover to movie audiences around the world. It’s a strange thing to have that power over the collective imaginations of the world, to make people who buy movie tickets in the millions feel like wry insiders.

The one bit of interest in the plot for Zero Hour comes in the form of the book’s use of the company’s recent slew of traumatic bullshit for its marquee heroes. The villain of the book – and I’m sorry if this is a spoiler that impacts you in 2018 – is Hal Jordan. And what’s curious after all these years is just how much Hal Jordan’s rationale for destroying the universe and recreating it in his own image is identical to the rationale for the invasion of Iraq. (This was when Hal was going around quite sullen because one of Superman’s enemies accidentally on purpose destroyed Coast City, which seems like it would be an event to render many folks quite sullen indeed.)

The one bit of interest in the plot for Zero Hour comes in the form of the book’s use of the company’s recent slew of traumatic bullshit for its marquee heroes. The villain of the book – and I’m sorry if this is a spoiler that impacts you in 2018 – is Hal Jordan. And what’s curious after all these years is just how much Hal Jordan’s rationale for destroying the universe and recreating it in his own image is identical to the rationale for the invasion of Iraq. (This was when Hal was going around quite sullen because one of Superman’s enemies accidentally on purpose destroyed Coast City, which seems like it would be an event to render many folks quite sullen indeed.)

But because this is comics he simply wants to turn back the clock to when everything was fine, you know, make the DC Universe great again. But then Green Arrow gets all huffy about him having become a frothing reactionary when, you know, he always was a frothing reactionary even though he drove around with you in a pick-up for a week once and doesn’t call the cops anymore when he smells those “special” cigarettes. It has always been a strange thing to me that Green Lantern was an idea that had absolutely limitless potential wedded to the most thunderously boring reactionary shithead of a character and mythos. Everyone likes Hal Jordan despite him having been, and I think I’ve made this point before, the only man square enough to figure out how to be in the military and be a cop at the same time without actually being a military cop. Hal Jordan is a narc, end of.

They stop Hal from putting the big rewind on the universe, worlds live, worlds die, I mean, seriously, these were five weekly issues, is that how long they had to make them?

Crisis on Infinite Earths is a story so big it took them years of research and preparation to be able to communicate the scale and grandeur they were going for. And the effort shows, because it reads like the people involved knew they were getting the chance to create something weird and dense and absolutely fucking bananas in the very best way. Zero Hour is a story so small Damage saves the day by glowing.

I don’t want to beat up on the book. It thought the best way to sell the audience on new directions for Hawkman and the Legion of Superheroes was to highlight those franchise’s best features, random and arbitrary plot contrivances. All the book can do in the face of trying to clean up the mess Crisis made is gesture vaguely in the direction of weak resolution to decades-old mysteries before pivoting to try to sell next week’s relaunch. Maybe not a good idea to use the crossover to shine a giant klieg light on the fact that those characters’ continuity has become so dense it’s a featureless gray mush and any attempt to make sense of all this bullshit is only ever just going to be more screaming.

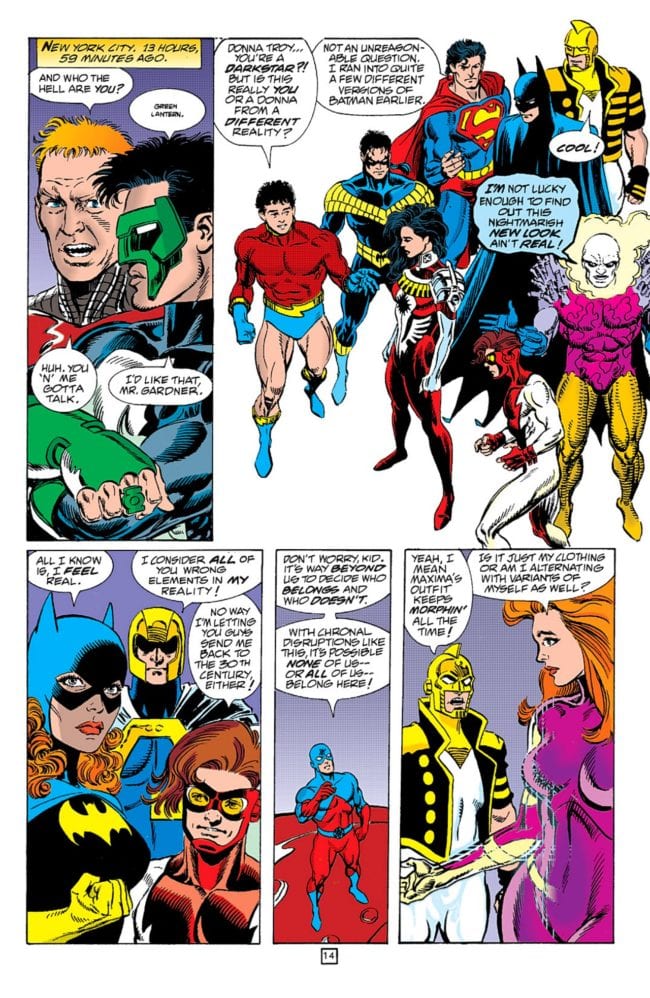

It gave me one moment of genuine mirth. There’s a bit where some of the usual assholes are sitting around jawing and Aqualad posits a very important question: “Donna Troy . . . you’re a Darkstar?! But is this really you or a Donna from a different reality?” “Not an unreasonable question,” Superman replies. “I ran into quite a few different versions of Batman earlier.” (He did, in a crossover, and its one of the better ones.) The Ray, you know, the 90s guy, pipes up with, “Cool!”

It gave me one moment of genuine mirth. There’s a bit where some of the usual assholes are sitting around jawing and Aqualad posits a very important question: “Donna Troy . . . you’re a Darkstar?! But is this really you or a Donna from a different reality?” “Not an unreasonable question,” Superman replies. “I ran into quite a few different versions of Batman earlier.” (He did, in a crossover, and its one of the better ones.) The Ray, you know, the 90s guy, pipes up with, “Cool!”

But the real money is the next line where, unprompted, after hearing that exchange, Metamorpho says, “I’m not lucky enough to find out this nightmarish new look ain’t real!”

Um. OK? Like, no one was probably going to say anything, bud. I promise. It’s cool.

But, you know – total same.