Creeping Death From Neptune: The Life and Comics of Basil Wolverton Volume One 1901-1941 by Greg Sadowski (Fantagraphics Books, 2014)

Creeping Death From Neptune: The Life and Comics of Basil Wolverton Volume One 1901-1941 by Greg Sadowski (Fantagraphics Books, 2014)

Who knew, or could ever have imagined, that Basil Wolverton, perpetrator of some of the weirdest and most grotesque eyeball kicks in mid-century American pop culture, once made a serious and concentrated effort to draw Mickey Mouse comics for Walt Disney?

Wolverton sent Mickey and Pluto to the surface of Venus, which he populated with his signature weird plants and creatures. The story is compelling, creepy, and a little bit dirty; what you might get if Charles Bukowski wrote Family Circus. The work is clearly not in the Disney mold, but it anticipates the early 1970s underground Disney-inspired work of Dan O’Neill and the Air Pirates, and is a lot of fun to read. It’s a shame that the Disney folks rejected Wolverton back in 1936, telling him that his work did not “measure up,” to their standards -- although they do get kudos for embracing the work of another comics master a few years later who, like Wolverton, hailed from Oregon: Carl Barks.

Wolverton’s science fiction version of Mickey Mouse is just one of the plethora of startling discoveries to be found in the just-released Creeping Death From Neptune: The Life and Comics of Basil Wolverton Volume One 1901-1941.This thick, 300-page art-packed hardcover is the latest work from comics historian Greg Sadowski, author of notable books on Bernie Krigstein, Alex Toth, 1950s horror comics, and primordial super hero comics, among others. Basil Wolverton’s son, the artist, syndicated editorial cartoonist and writer Monte Wolverton (Chasing 120, Spacehawk, The Wolverton Bible) apparently gave Sadowski full access to his father’s papers. The result is a book rich with heretofore unknown material that will fascinate not only Basil Wolverton fans, but anyone interested in comics history and pop culture.

For example: it is 1926 and a 17-year old “Bay” Wolverton gets wind of a film being made twenty miles south of Eugene, Oregon -- where he was living at the time. He takes a ride, Clyde, and finds himself in the middle of the location shooting for Buster Keaton’s The General. Creeping Death has Wolverton’s photos of Keaton on the set, and even one of Wolverton himself leaning on a tripod movie camera that filmed Keaton’s masterpiece. For certain aficionados of a certain pocket of culture, it doesn't get any better than stuff like this previously unknown record of two great artists crossing tracks.

The Keaton episode is just one one many fascinating parts of Wolverton's young life recounted in Creeping Death From Neptune, all arranged in biographical framework. In what appears to be a fetching outgrowth direct from Wolverton’s imagination, Creeping Death appears to have mutated from a one-volume art book into a serious, comprehensive, multi-volume biography that will stand as the definitive work on Basil Wolverton, one of the twentieth century’s most singular artists.

Wolverton, like many of the older comic book greats, was a one-man band: writing, penciling, inking, lettering, and providing color guides for his comics.

He was born, raised, and lived his life in woodsy Oregon and Southern Washington State, where the skies are often cloudy, the air often misty with light rain, and where the mind often slips into a dream state during the day. Wolverton’s territory is not far from where Bigfoot sightings have been reported for decades, a creature that could easily have stepped out the pages of a Basil Wolverton comic book story. Wolverton’s gross, distorted figures and characteristic shapes and textures have led some to call his work the “Spaghetti and Meatball School” of comic art.

Over the years, other comic artists living in this sleepy part of the country have created work that appears to be connected to or inspired by Wolverton’s approach, including Peter Bagge, Charles Burns, and Pat Moriarty, to name a few.

Among the emerging new crop of Seattle cartoonists is a group that might be called the “Goop School” and which includes Max Clotfelter, Tom Van Deusen, John Ohanessian, and James Stanton -- a group whose work appears to be in direct lineage with Wolverton’s.

This ambitious multi-volume work on Wolverton is published by Fantagraphics, headquartered in Wolverton’s neck of the woods and responsible for several previously released books on Wolverton, including: Spacehawk (2012), Culture Corner (2010), and The Wolverton Bible (2009).

This volume, the first of two, or perhaps three, in an art-filled biography, covers Wolverton’s life from birth and childhood up to the first few years of Spacehawk and the first shakings of Powerhouse Pepper, landmarks in Wolverton’s career and features that will be familiar to any fan. The book is roughly eighty-percent art and twenty-percent text. Sadowski’s well-written, densely detailed narrative is organized into chapters of illustrated biography separated by generous chunks of “art pages,” which have their notes. This is a thoughtful and successful design.

This volume, the first of two, or perhaps three, in an art-filled biography, covers Wolverton’s life from birth and childhood up to the first few years of Spacehawk and the first shakings of Powerhouse Pepper, landmarks in Wolverton’s career and features that will be familiar to any fan. The book is roughly eighty-percent art and twenty-percent text. Sadowski’s well-written, densely detailed narrative is organized into chapters of illustrated biography separated by generous chunks of “art pages,” which have their notes. This is a thoughtful and successful design.

One of the interesting things about Sadowski’s books is that he manages to find a way to showcase reprints of carefully selected and restored comic art without sacrificing detailed narrative and notes. In his 2009 book, Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes 1936-1941 (which includes some Wolverton comics), Sadowski hit upon the scheme of presenting his selected stories up front as a thick portfolio, with a second section of detailed commentary on the stories and their contexts in the back. One can read these books just for the comics, or for the full experience offered. It works well both ways.

As a comics historian and writer, I appreciate Sadowski’s and Fantagraphic’s accomplishment with volumes like Creeping Death and Supermen! because they create a precedent for including more information and writing about comics in future reprint volumes – which is something that has been missing from many modern comics reprint books. Understandably, publishers want to shy away from stale academic treatises that will only appeal to a few people and hurt sales. However, it is not enough to merely reprint cool comics; it is important to understand and articulate in a detailed fashion why anyone should care about reprints of very old comics, and that includes presenting well-researched historical information and context in a way that makes the book marketable to folks who primarily want to read and enjoy the comics.

By quoting extensively from Wolverton’s own diaries, letters, and a key 1971 interview, Sadowski lets Wolverton tell his own story as much as possible. For example, here is 16-year old Basil Wolverton recounting an early effort to find work as a professional cartoonist in 1925:

“I am sixteen years old now. Mom wanted to take her trip back East this summer but there is not enough money. I thought sure we were going to get to take it but I guess now we are not. I worked a little over a month now in the cannery, right after school and earned $96.88, which helps a bit. I am now trying to sell my cartoons to some syndicates. I made a few strips and called them Simple Simon and These Modern Inventions, and sent them to the King Features Syndicate at New York. The King Features Syndicate sent them to the International Feature Syndicate, just a block away. They both had no use for the cartoons, so sent them back and I made some more…”

What emerges is the portrait of a gifted, hard-working artist-cartoonist in the first half of the 20th century who was indefatigable and simply would not quit. We see some of Wolverton’s earliest drawings and cartoons. We see photos of him as he matures from a young boy into a young man who looks striking like his character, Powerhouse Pepper. We learn about his vaudeville act and are treated to lots of early unpublished art.

It’s not long in the narrative before Wolverton’s science fiction art appears, meticulous and strange. Very early, Wolverton established the dual strategy of creating serious science fiction art and screwball humor comics as a way of diversifying his offerings and keeping himself afloat. Even so, as his letters and journals detail, Wolverton’s early years were pretty lean as he pitched comic strips to syndicates unwilling to gamble on the new, oddball artist.

In 1936, Wolverton, flat broke, took a train to New York to try to sell some work, and that’s where – like Jack Cole who also arrived in town around the same time – he discovered comic books as a source of desperately needed income. Sadowski has a good grasp of comics history from this period – especially the publishers – and he uses that to help tell Wolverton’s story. For perhaps the first time in print, the full details of Monte Bourjaily and his ill-fated comic book scheme are laid out. Bourjaily, as Sadowski explains, was a noted figure in the publishing world at the time. He became general manager of the large United Features Syndicate and had developed and guided several successful features to stardom, including Al Capp’s Li’l Abner.

Wolverton crossed paths with Bourjaily as he made the rounds of various syndicate offices during his short New York tour. This led to Bourjaily recruiting Wolverton for his new comic book venture, Circus The Comic Riot, which published three issues before closing and published early work by Jack Cole, Will Eisner, Bob Kane, and Basil Wolverton.

At this point in the book, about a third of the way through, the narrative becomes something bigger and even more important than Wolverton’s story. It’s a lost piece of comics history recovered.

Because most of the writers and artists who contributed to American comic books in the 1930s and 1940s lived in the vicinity of the publishers in New York City, there is very little of a written record that remains of their day-to-day dealings. Few – if anyone – involved in making comic books at that time felt a sense of history. Only scraps of documentation have survived – a ledger here, a few notes there and some original art that usually sells for a lot of money and disappears into a collection.

Basil Wolverton was one of the very few prolific, major comic book artists of the 1930s and 1940s in America who did not live in New York City. He conducted his business by mail from his home in Vancouver, Washington. Because Wolverton – a meticulous and organized person – saved his correspondences with comic book editors and publishers, and then his son Monte also preserved this material, we now have in these documents a precious glimpse of the comic book business in America in the 1930s and 1940s.

For example, we discover that while Monte Bourjaily didn’t give Wolverton’s career the publishing and income boost he promised, he did provide a lot of valuable professional development training to Wolverton. Because he also worked with Cole, Eisner, and Kane in their formative years, Bourjaily emerges as a major influence on early comic books, despite the fact that he published very little. His comments to Wolverton are detailed, encouraging, and almost fatherly:

“Thanks for the autobiographical notes, I will have a better picture of you now. One reason I asked for them was to know where your experience lay so that I could make suggestions from time to time that would grow out of your experience.”

Bourjaily coached Wolverton over several months, teaching the young artist methods for producing and delivering his art to meet the specific needs of the market:

“It’s a good thing that you have gone to the trouble of finishing the drawing in both cases because it enables me to point out to you that you have overdone your black. Perhaps my specifications were not clear enough, but we plan to use all these pages in color. That means you should plan your finished drawing to carry such black lines as you want to appear in black in your key plate… Then get a positive photostat of each feature and color the Photostat as a guide to the engraver to lay his colors.”

Later, Bourjaily has apparently learned a new method for indicating color that is much easier, and he passes that on to Wolverton. One wonders how many times this sort of important information was discussed among editors and artists in the 1930s and 1940s? Did Bourjaily also school Jack Cole in indicating color?

In any case, it’s clear that Monte Bourjaily played a large role in the life of Basil Wolverton, who named his son "Monte." In addition to quoting extensively from Wolverton’s correspondence with Bourjaily, many other editors and publishers are given voice in Creeping Neptune, making this a valuable source -- one of the very few -- for understanding a little something about the actual business of comic books in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Creeping Death is resplendent with about 240 pages worth of rare photos, tear sheets, cartoons, unpublished art, manuscript pages, journals, letters, sketches, rare comics, covers, and more. Several complete stories are reprinted in restored color, which makes it worth the price of admission alone.

It would be hard to imagine a more satisfying book for a culture vulture. On nearly all levels, the book delivers: selection, presentation, scholarship, writing, design and production. If there is one dimension to this project that is lacking, it is Sadowski’s reluctance to offer much of his own critical assessment and synthesis of the work he presents.

In his summer 2014 essay in Artforum, “Eye of Doom, Hand of Glory,” Art Spiegelman offers the kind of critical commentary that drags old comics out of the past and makes them vibrate with relevance in our time: “Basil Wolverton’s all-seeing Eye of Doom will absorb and eat you unless you see it before it sees you.” Later, Spiegelman writes that Wolverton’s work “leaps out and rescues you from a sea of anonymous drawing.” It’s this sort of trenchant commentary on the impact of the art itself that is missing from Creeping Death.

However, given certain other comics historians who tend to put themselves in front of their subjects to the detriment of their projects, it seems better to go towards restraint. Any author of such a book has a monumental job on their hands, to sift through the artifacts of a life and shape a clear narrative in a format that will appeal to a broad audience. While more critical insight is needed to grasp Basil Wolverton’s unsettling and provocative art, it is a book like Creeping Death From Neptune that lays the most solid foundation imaginable for such work to come.

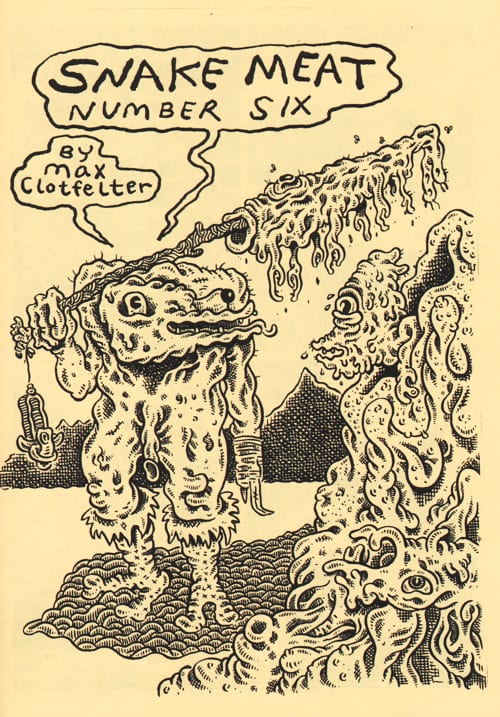

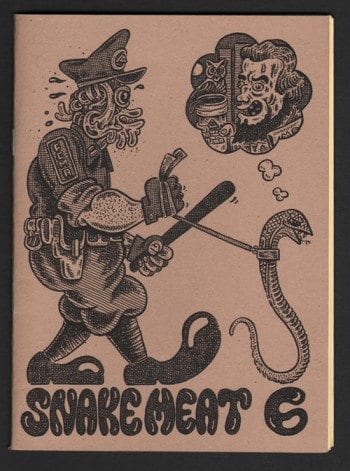

Snake Meat #6 by Max Clotfelter

Snake Meat #6 by Max Clotfelter

(Self-published, November 2014)

There’s a mesmerizing Youtube video in which a soft spoken comics fan reverently thumbs through his copy of Mystic Comics #6, published in 1952 and containing “Eye of Doom” by Basil Wolverton.

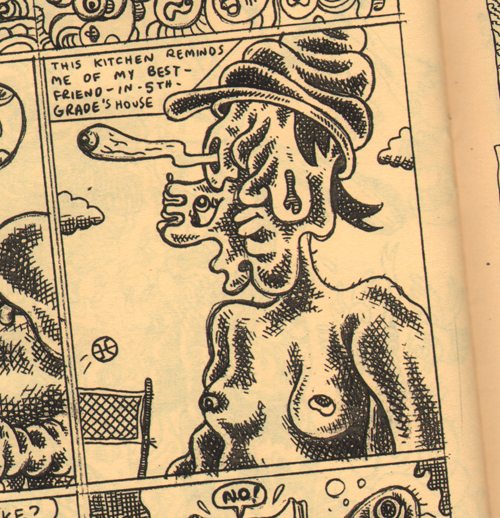

When he gets to the classic Wolverton image of a giant floating eye gooping up humans, the YouTuber is dumbstruck and can only utter: “trippy, very trippy.” That’s just the sort of reaction the dripping, gelatinous and fleshy creatures and landscapes drawn by Seattle "Goop School" artist Max Clotfelter in Snake Meat #6 elicits: trippy, man… very trippy.

In Clotfelter’s 40 page, 5.5” x 7.5” self-published comic – one of at least 20 or 30 he has so far produced – our eyes are assaulted by images from a 21st century bio-nightmare. This particular effort is skimpy on narrative, but no matter. Clotfelter, who won a $1,000 cash award from a Seattle arts organization in July 2014 for his comic, "Rough Things I've Seen On My Daily Walk to Work," has plenty of stories to tell in other books. Here, we are mostly concerned with surrendering to ever higher levels of weirdness.

Part post-apocalyptic and part bigfoot screwball, the pen-and-ink images in Snakemeat are as unsettling, distressing, and as absurd to contemplate as fresh roadkill.

Clotfelter and Wolverton have some common ground in their love for creating dense textures with pen strokes. Both artists seem driven to lay down acres of cross-hatching. Eventually, all the fury and passion in these zillions of tiny marks adds up to a powerful effect. Clotfelter's fractal fleshy folds ripple across bodies and landscapes like cancer cells gone wild on spring break, and the result is a brief shift in reality. Take in the images in Snake Meat #6 long enough and, if you weren't already, you’ll start to become fascinated by earfolds and skin tags, acne and wounds.

Wounds seem to be an integral part of Clotfelter’s work, both physical and psychic. It’s the sense of a dark undercurrent in this artist’s work, that he is working out some kind of demon, which elevates what could be well-executed stoner art to higher levels of resonance with the reader. Clotfelter’s mangled victims have brave smiles, and his more or less normal appearing people inevitably carry frozen expressions of dread.

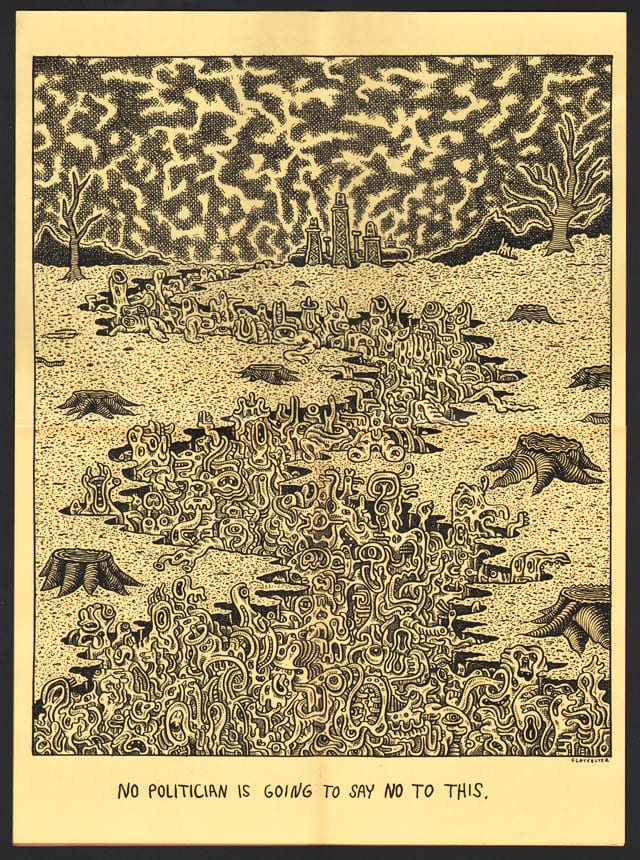

In a fold-out centerfold, “No Politician is Going to Say No to This,” Clotfelter creates a blighted landscape with a science fiction chemical factory on the distant horizon, pumping out toxins.

The ground is ruptured (again, a wound), and in the fissure are zillions of nightmare organisms, all eyes and pseudo pods, slimy and interlocking like a pie full of maggots. The vision of hell is streaming through the crack in the world towards the reader as surely as Wolverton’s Eye of Doom preys on those who fail to see it first. The concept is hardly fresh, but the dark vision has something compelling to offer – and Clotfelter has found his way around a pen nib and a brush. Clotfelter is one to, unh, keep your eye on.

________________________________________________________________

Paul C. Tumey is a writer, artist, and cartoonist in Seattle, WA. He co-edited and wrote for THE ART OF RUBE GOLDBERG (Abrams ComicArts 2013), and wrote the introduction to THE BUNGLE FAMILY 1930 (IDW Library of American Comics, 2014).