In 1940, publisher Everett M. “Busy” Arnold moved his Quality Comics line (Crack Comics, Smash Comics and other percussive titles) from New York City to Stamford, Connecticut and brought a band of cartoonists with him. Among them were Jack Cole, Will Eisner, Reed Crandall and Gill Fox. The major characters that his magazines would deliver to the nation’s newsstands were Plastic Man, Blackhawk, The Spirit, The Human Bomb and, eventually Torchy.

In 1940, publisher Everett M. “Busy” Arnold moved his Quality Comics line (Crack Comics, Smash Comics and other percussive titles) from New York City to Stamford, Connecticut and brought a band of cartoonists with him. Among them were Jack Cole, Will Eisner, Reed Crandall and Gill Fox. The major characters that his magazines would deliver to the nation’s newsstands were Plastic Man, Blackhawk, The Spirit, The Human Bomb and, eventually Torchy.

Arnold had worked in printing since graduating from college. He was involved in printing the comic books that Cook and Mahon had begun since leaving the fold of the pioneering Major Malcolm-Wheeler Nicholson. This line included such winning titles as Funny Pages, Funny Picture Stories and Keen Detective Funnies. Busy had been following the lack of success of these comics, so he decided to start his own line and hook up with some affluent partners. He made a deal with The Register & Tribune Syndicate, owned by the affluent Cowles family, and acquired two more well-connected partners. He started with Feature Funnies, a simulacrum of the pioneering Famous Funnies, which reprinted newspaper comic strips. Soon after the advent and impressive sales of Superman, Busy realized that superheroes were selling better than reprints of Joe Palooka and Dixie Dugan. Changing the name of the magazine to Feature Comics, Arnold set about acquiring his own stable of super humans.

Born in New Castle, PA, Jack Cole had originally come to New York to sell gag cartoons to slick weekly magazines like Collier’s. He graduated from high school in 1933 and married his high school sweetheart, Dorothy Mahoney, the following year. He got a job with the American Can Company and “started mailing out cartoons to magazines.” His first sale was to Boy’s Life in 1935. Cole was well-liked in his home town, the kind of boy just about everybody knew was going to make good. So the local merchants loaned him $500 so he and Dot could take Manhattan. Settled in their small apartment for some months and unable to sell very many gag cartoons or to get paid for the few he managed to sell, Cole decided to try the newly born comic book business. He found employment with the Harry “A” Chesler shop, one of the first to supply art and editorial for the adventurous publishers trying to launch comic book lines.

Among the artists who were toiling in the Chesler sweatshop at the time were Charles Biro, Bob Wood, Jack Binder, Fred Schwab, Ken Ernst, Fred Guardineer and Gill Fox, who became a close friend of Cole. As Fox remembered the layout at the shop on Lexington around 29th Street, there were three rows of drawing boards, two aisles between them. “Jack sat on the left side in the back.” Most of the artists were between 18 and 23. At first, sitting at his drawing board in the Chesler funnies factory, Cole drew mostly one- and two-page humor features---Joe Ticket (The Picket), Smart Alec, Ima Sphinx, Slim Pickens, etc. Screwball stuff in the manner of such newspaper comic strips as Smokey Stover and Salesman Sam.

In 1939 Cole began to really branch out and attempt more straight adventure pages. Superman had come along in Action Comics the year before, followed by Batman in Detective Comics in the spring of '39. Their rapid and conspicuous success convinced publishers that adventure and fantasy definitely sold better than humor and whimsy. Cole, still eager to achieve a secure income, must have realized that if he limited himself to a couple of funny filler pages comic book, he’d never make it. Adventure cartoonists selling stories up to 11 pages long for $5 to $10 per page could earn up to $110.

One of Chesler’s clients was MLJ. Less formal than MGM, these initials stood for the first name initials of the comic book line's three partners---Morris Coyne, Louis Silberkeit and John Goldwater. The artwork and scripts for the earliest issues of their new titles were provided by the Chesler shop. The MLJ magazines were Blue Ribbon, Top-Notch and Pep and the initial contents were an uncertain mix of fresh material and what looked like old items out of Chesler’s trunk. Morris, Louis and John came to their senses fairly soon. They fired Chesler and hired some of his better employees to work directly for them. Biro was put in charge and Cole also made the switch. Unlike many of his 1930s contemporaries, he’d already discovered that the comic book page was not a newspaper Sunday page. He created imaginative splash panels, broke up each page into unconventional size and shapes and he was bringing movie techniques like close-ups, down shots and long shots into his work.

Cole’s first costumed superhero was the Comet, who began his violent career in Pep Comics #1 (January 1940). Cole’s splash panel shows the brightly costumed hero whizzing across the night sky and nearly flying right off the page. Cole also provided his own blurb: “Smash adventures of the most astonishing man on the Earth,” In those days, when superheroes were proliferating like mushrooms in a damp cellar, the Comet was exceptional. For one thing, he killed people, lots of them, and usually with glee. He disintegrated them with powerful beams from his eyes, dropped them from great heights.

Late in 1939, Jack Cole got a comic book of his own to edit. The first issue of Silver Streak Comics (cover dated December 1939) was published by a company that later became Lev Gleason’s Comic House, Inc. The first two issues of Editor Cole’s comic book lead off with his own work, namely The Claw. The quintessential sinister Oriental, The Claw was “a monster of miraculous powers who is out to dominate the universe” and had all the attributes of the better known Dr. Fu Manchu. What gave him the edge, for young readers who doted on his early misdeeds, was the fact that he could grow several stories high at will. Seeing The Claw swelling up out of the midnight ocean in the path of an unsuspecting ocean liner or watching squeeze a disloyal minion to death in one huge fist while chuckling. “Die, swine!” were awesome experiences.”

Joining the cast in the third issue was The Silver Streak, missing from the magazine named after him until then. Joe Simon did the introductory adventure. The next month Cole was drawing an entirely new Streak, a costumed super guy, billed as “the fastest man imaginable.” Cole was obviously having fun with this one, stuffing it with action, violence, explosions, monsters, pretty girls and humor.

On the back cover of the sixth issue, Cole ran this announcement---THE MONSTER GIANT OF TERROR RETURNS TO THE PAGES OF SILVER STREAK.” Yes, the Claw, who’d been on a few issue vacation, was coming back and, much to the surprise of readers, he was battling Daredevil. The character had only shown up in the magazine in that sixth issue, drawn in clunky style by Jack Binder. Cole took over the character and drew a long story, He managed to throw in the Second World War, introduce Daredevil’s girlfriend Toni, take readers to the Claw’s mountain stronghold in far-off Tibet, show his invasion army heading for America via their own private tunnel and popping up in the streets of New York. The epic battle between Daredevil and the Claw was the biggest thing to hit the town since King Kong.

The next issue Cole started drawing the character and did something audacious. He pretends that he’s working with an old established character and not another Chesler clunk and that the fellow in the crimson and blue costume is the star. He proclaims DAREDEVIL BATTLES THE CLAW. The long story commences with a socko splash page that shows the Daredevil, the Claw and a sparsely clad young woman about to be burned at the stake while a half dozen sinister Orientals look on. There is also a disclaimer—WARNING! You are about to read one of the most astounding tales ever portrayed in a comic magazine! If you have a weak heart. We advise you NOT to venture further!” When Charles Biro began working for Gleason, he adapted some of Cole’s exuberant techniques on the covers and splash pages he used when he was turning out his Daredevil stories.

By late in 1940, Cole was installed with Quality and his first creation was Midnight, debuting in Smash Comics #18 (January, 1941). This was a fellow who fought crime in a business suit, snap-brim hat and a mask and he was something of a Spirit surrogate. But since Cole and Eisner were original and inventive, the two features developed in different directions. While both men refused to take the profession of masked crimefighter completely seriously. While Eisner became more interested in urban melodramas, Cole pursued fantasy and science fiction and, on occasion, a somewhat unsettling approach to violence.

Midnight began his career as an even bigger loner than the Spirit. Working without benefit of sidekick, police contact or lady friend. He was fond of gadgets, inventing “his secret vacuum gun, an automatic that throws a suction cup which is connected to a self-winding reel of fine silk cord strong enough to hold a man’s weight.

The first two cases he cracked involved graft and corruption in the construction business and an orphanage. In his third foray, though, Midnight “slashes out against the supernatural” and combats a turbaned no-good named Chango. This bewhiskered wizard can make safes sprout legs and can cause buildings to rise up and fly away and could change Midnight into a puff of smoke. The masked hero uses a hypnotic dart, shot into Chango’s backside to subdue him.

As the series progressed, Midnight took on a small crew. Whereas some costumed heroes at the time were taking on teenage lads for sidekicks, Midnight teamed up with a monkey. A talking monkey named Gabby. And next came a white-bearded mad scientist known as Doc Wackey. Cole’s artwork reached a new plateau on the feature. His line became finer and more assured and the layouts and staging more inventive and bold. One area in which he competed with Eisner was with logos and splash panels. The Midnight logo, new each issue, was almost always a part of an elaborate design. The time and effort he was lavishing on his Quality work eventually caused him deadline problems.

In autumn of 1942, in order to concentrate on Plastic Man, Cole was forced to abandon Midnight. His penultimate continuity, a two-parter he titled The Death of Midnight and prefaced with a warning—“We hope you don’t really believe this bizarre adventure.” And it truly was bizarre.

As the result of a rough and tumble bout with a baldheaded crook, Cyclops Ceylon, Midnight falls from a cliff and is killed. When his soul reaches St. Peter, he asks if he can go to Hell instead of Heaven, explaining, “You see, being a crimefighter, I’d like nothing better than to have a crack at the worst criminal of all!...The DEVIL!” He gets his wish and goes sliding down and down to meet not only with Satan himself but a sexy redhaired lady who turns out to be the devil’s spouse. While a resident of the fiery kingdom, Midnight leads a revolt of the other lost souls. Midway through that, he is snatched back to life.

Seems a mistake has been made and he wasn’t meant to die at all.

Cole bid him farewell with the story in Smash #38 (December 1942) and Paul Gustavson took over. Cole didn’t resume working on the masked crimebuster until 1946.

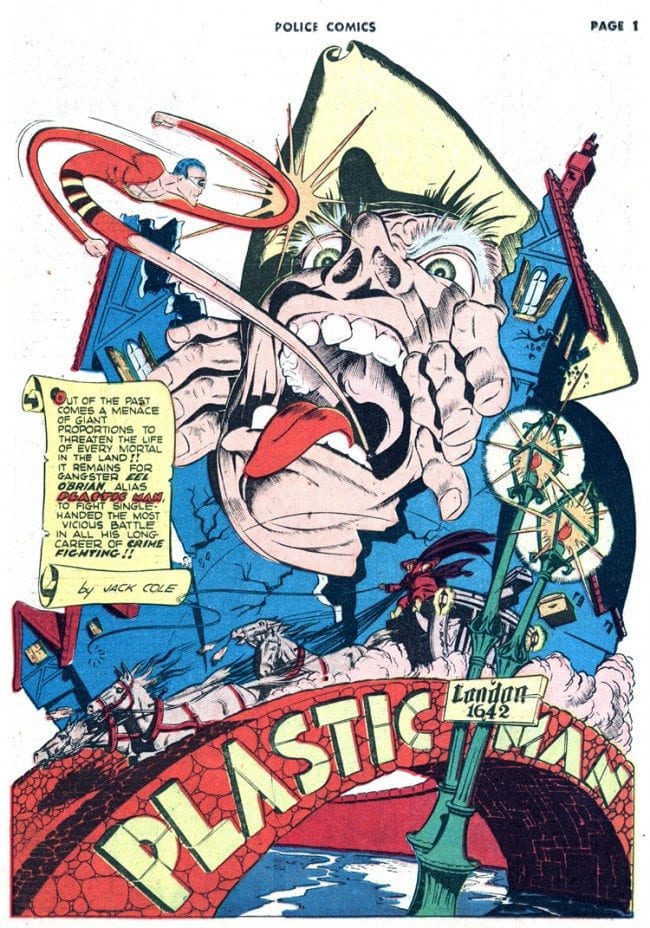

Jack Cole’s magnum opus was Plastic Man who bounced into view in Police Comics #1 (August, 1941) Again, Cole wrote his out blurb, proclaiming, “From time to time the comic book world welcomes a new sensation! Such is PLASTIC MAN!! The Most fantastic man alive!” Cole had here a feature where he could make use of all the skills he’d been developing. His drawing style, a blend of the straight approach and the exaggerated and the distortions and exaggerations of animated cartoons, was ideally suited to depicting Plas’s adventures.

Cole had a fondness for making heroes out of reformed crooks and in this case it was Eel O’Brien, “the toughest gangster afoot…wanted by the police of eight states,” who went straight and became Plastic Man. While taking part in a safecracking job at a chemical works, acid spilled on Eel. Left to fend for himself by his gang, he wandered out of the city, “through swamps, then up a mountain side.” He passed out and awakened to find he’d been cared for by a kindly monk who ran a peaceful mountain retreat. The monk’s faith caused Eel to reform on the spot, and shortly after his reformation he realized that the acid bath had given him the ability to stretch his body into all kind of shapes. Another fine example of funny book science. Eel realizes, “What a powerful weapon this would be…AGAINST CRIME!”

Within a year or so Cole grew tired of the dual identity notion and Plas was just plain Plas from then on---when he wasn’t being a chair, a snake, an umbrella stand, a beautiful actress, or a throw rug. In issue #13 Woozy Winks, who looked something like the movie comedian Lou Costello, came along. After using his gift of invulnerability to commit a few crimes, Woozy also reformed and joined Plastic Man as his sidekick. Their subsequent adventures mixed crime, violence, fantasy and satire in the Midnight manner.

Among the criminal problems that were handled was the Crime School for Delinquent Girls, It was run by Madam Brawn, a strong, hefty lady who wore overalls and smoked cigars. Quite obviously meant to be a lesbian. It took two episodes to settle her. Then there was a gigantic eight ball, as big as juggernaut that knocked over buildings and a strange small creature who was just arms and legs known as Hairy Arms.

One of the most disturbing narratives during the first year was in the 11th issue (Sept 1942). It opens with a mad scientist in 17th century London, who has learned how to create a gigantic monster. But his creation kills him. The scientist, Cyrus Smthe, who also practices black magic, is buried but his brain lives on. Now in London 1n 1942 an American flyer is felled by a Nazi bomb near the gravesite. In a wonderful example of funny book science, the 17th century madman’s brain gets put into the pilot's head and he returns home controlled by the scientist’s brain. He grows to a great height and first kills his fiancée and then crushes both his father and his mother. At this point Plastic Man destroys him. But buried again, the brain promises, “the BRAIN of CYRUS SMYTHE WILL RISE AGAIN TO PLAGUE ALL MANKIND!!!”

Later stories became a bit milder and gradually lightened. Throughout the '40s, Jack Cole stuck with his hero. He was also drawing a good deal of funny stuff for Quality, most of it in the one page filler category. Wun Cloo, Don Tootin, Windy Breeze and Burp the Twerp. Burp, billed as the Super So-and-So, was bald, had a shaggy white moustache, wore a peppermint-stripe bathing and had a figure like an over-ripe balloon.

Jack Cole, in the middle 1950s submitted a batch on gag cartoons to Playboy and came to the attention of Hugh Hefner, who had grown up reading comic books and was a fan of Plastic Man. His full page gags, done in bright watercolors, soon became a staple of the magazine. Cole’s lifelong ambition to become a very successful gag cartoonists was being fulfilled. But when, 1955, when Hefner suggested that he relocate to the Chicago area Cole was less than enthusiastic. But the money was compelling. He wrote to his friend Gill Fox, explaining, “Middle of January the boss is moving us to Chicago. Swore I would never leave these old hills. But he is offering so much green bait what’re you going to do? The saddest part is leaving old friends…But it’s the biggest pile of eagle-shit that ever landed on us, so I’m gonna grab a fork and wade in.”

In 1956, his report to Fox said, “After near-month of hotels, house-hunting…Bought a place about 40 miles from Chicago---that’s as near as I want to be to the joint. Hef offered me a staff job but I prefer to work at home.” His success with Playboy continued. The Females By Cole were collected into a book, reprinted on cocktail napkins and otherwise merchandised, Cole was also assigned four and five page full-color spreads. He didn’t miss his days with Quality. In fact, when Arnold had tried to hire him back, Cole told him “that I was going to be the best damn cartoonist in the gag field.”

1958 saw another of his lifelong dreams come true when he sold a comic strip to the Chicago Sun Times Syndicate, part of the Marshall Field empire. Betsy and Me was drawn in simple UPA animation style and the gags were built mostly around the stupidity of its central character, a department store floorwalker, Chester Tibbets, and his wife Betsy. The syndicate loved it, offering Cole a contract with in a few days of his submission. Dorothy Portugais was an editor at there and she told me theirs was the first syndicate Cole had shown the strip to. He’d just walked in off the street one day after a visit to Playboy with about four or five weeks of penciled dailies and two or three inked sheets as well. Nobody up there had ever heard of him and they didn’t find out until after he was signed up that he was a veteran of nearly 20 years in comic books and one of Hefner’s favorite cartoonists. According to Portugais the new strip was successful from the start and picked up newspapers throughout its run. She saw Cole every week and had lunch with often. She liked him, says he was a pleasant, easygoing man.

On the afternoon of August 15th that year, Cole went to a sport shop in nearby Crystal Lake to buy himself a .22 single-shot Marlin rifle. Getting back into his station wagon, he drove for a while. Then he pulled over and shot himself in the head. He left two notes, one to “Whom it may concern," In this one he requested that his wife be notified and to make sure a neighbor was with her when she got the news. The last line was “Please forgive me, hon.”

When Gill Fox heard about this, he said, “That was typical of Jack. Not blaming anyone but himself.”

Fox, a Brooklyn boy, was a professional cartoonist for most of his adult life. After working for the Fleisher animation studio in Manhattan, he switched to the Chesler shop and then moved up to Busy Arnold’s operation. He once told me how he accomplished that bit of upward mobility. “I was there at Chesler and then I went through a period of about six months of no work,” he said. “I was riding on Lexington Avenue bus. I knew Arnold’s address and, instinctively, something told me to get off the bus and go up there with no appointment. And I did, and saw Ed Cronin, who was editing. That’s how the whole thing started.” He sold two filler pages for $8 each.

When Arnold was getting ready to move the company to Stamford, Cronin invited Fox to come along and be his assistant for a salary of $25 a week. “I say, my God, I can get married.” Once settled in the Gurley Building, Fox “had to keep things going---in addition copy editing, there was production. If a new artist came in, I could look at his stuff, but I couldn’t buy a feature. I’d have to go to Arnold.” Fox rose in the Quality office and when Police Comics was added, Fox was made editor. And in that capacity he got to know Jack Cole, who had settled in Connecticut with his wife.

He considered Cole one of the only true geniuses he ever encountered. But as the number of pages devoted to Plastic Man increased, a problem arose. Cole became a notorious for missing deadlines. On one occasion, Fox decided to pay a call at the Cole residence. He was certain that Cole was there in his studio and had the distinct impression that his friend was hiding from him. In addition to editing and working with such artists as Lou Fine, who also became a close friend, Paul Gustavson and Alex Kotzky, another friend, Fox drew covers and turned out filler pages—Wun Cloo, Slaphappy Pappy, Poison Ivy.

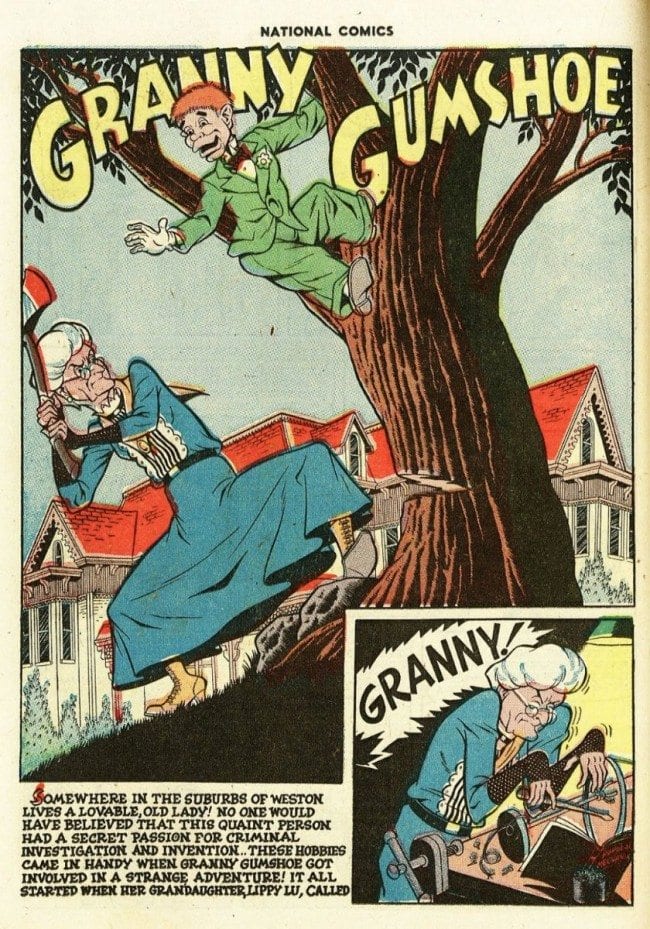

He was drafted in 1942 and served with the 63rd Infantry Division. And worked as a cartoonist in the Paris office of the Army magazine Stars and Stripes. Back with Arnold in 1946, Fox drew more humor features, including Granny Gumshoe, about a little old lady detective.

Fox left comics to go into the army, serving in the 63rd Infantry Division. He eventually served as a cartoonist on the service Stars and Stripes in Paris. Back home in 1946, drawing more humor features and taking a turn drawing the sexy blonde Torchy. She was the creation of Bill Ward, the breast fetishist, and Fox was needed to supply extra stories when Torchy got a book of her own. “Now, I was still very conservative in my thinking,” Fox told me, “but I loved drawing pretty girls.”

He left comic books in 1950 and joined the staff of Johnstone & Cushing to draw advertising comics and strips. Among his coworkers were Dik Browne, Stan Drake and Lou Fine. While there he displayed an ability to work in a variety of styles. This ability served him well when he collaborated with writer Selma Diamond on a moderately realistic called Jeanie in the early 50s. He did a Sunday page for the New York News called Bumper to Bumper.

In 1961 Fox became the artist on the long-running NEA panel Side Glances. This called for the mastering of yet another style. He felt he had achieved another of his major goals, to draw a successful syndicated feature. That success allowed him to achieve yet another goal, a home in rural Connecticut. Like some of the cartoonists we’ve met in earlier installments, Fox was abruptly fired in 1980.

He next ghosted some children’s books and became a political cartoonist for two Connecticut newspapers The Connecticut Post and The Fairfield Citizen. In his later bios he always put “Nominated twice for the Pulitzer Prize.” He’d discovered that anybody working on a newspaper could submit a nomination. So he did, twice.

Fox was a matchmaker for fellow artists. He got Stan Drake the job of drawing The Heart of Juliet Jones soap opera strip by touting him to the writer Elliot Caplin. He suggested that Ramona Fradon take over the Brenda Starr, Reporter strip and he introduced me to the NEA feature editor who hired me to co-create Star Hawks.

Gill Fox became ill in 2003 and spent his last days in a Connecticut hospice. He passed away on May 15th of the following year at the age of eighty eight.