Several cartoonists who drew Superman over the years migrated to Connecticut. Usually they settled in Fairfield County, which is the closest county to Manhattan. Among them were Wayne Boring, Curt Swan and Jerry Ordway.

Boring had been Joe Shuster’s assistant and sometime-ghost since the late '30s. He had answered an ad that Siegel and Shuster had placed in Writer’s Digest and got the job. Moving to Cleveland, where the young partners had a studio, he began working on several features they were producing for the recently born DC comics—Federal Men, Spy, Slam Bradley and Superman. “We had an office about twelve by twelve with four drawing boards set up there,” he once said. “It was the smallest office in Cleveland.”

He rapidly modified his style to more closely resemble Shuster’s diagrammatic cartoony style, which was much influenced by what Roy Crane's Captain Easy Sunday pages. The Man of Steel’s popularity grew impressively after his arrival from Krypton and publication in the first issue of Action Comics (dated June 1938). Siegel and Shuster soon moved their studio to Manhattan and hired several new hands. In 1939 a comic book featuring only the adventures of Superman appeared, as well as a daily and Sunday newspaper strip. By the early 1940s, Boring was drawing several sequences of the strip in addition to his comic book chores. By the middle '40s he was responsible for illustrating most of the newspaper strip continuities. Gradually leaving Shuster’s Crane-derived look, he adopted a slicker, more muscular way of drawing. He beefed up both Superman and Clark Kent and made Lois Lane a great deal sexier. When I once asked him how he came up with this new look for Superman, he told me he had been greatly influenced by cartoonist/illustrator Frank Godwin, whose best-known comic strips were Rusty Riley and Connie. I’ve never been able to see any resemblance between his stuff and Godwin’s, but possibly Godwin’s influence was by example rather than by style. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were put out to pasture in the later 1940s, triggering a decades long period of struggling for them.

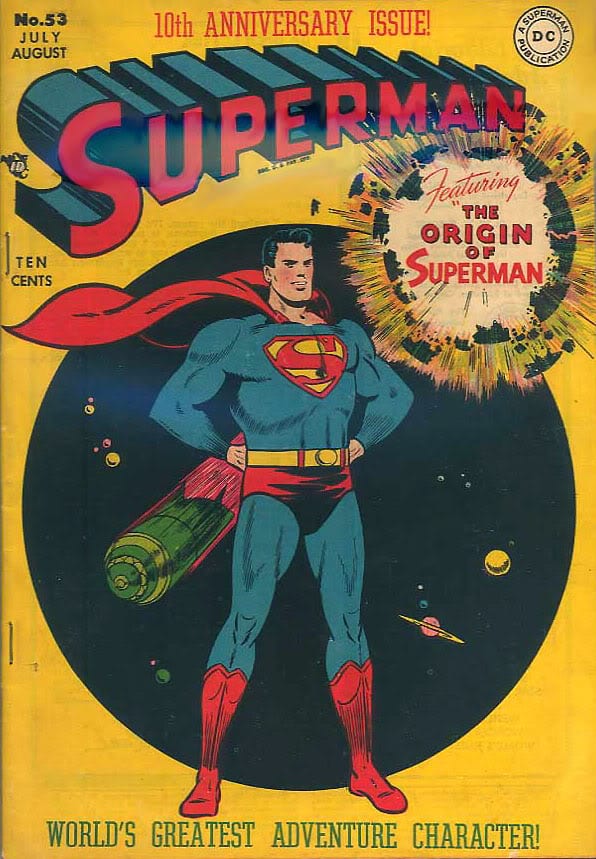

Boring stayed on and became the chief artist on Superman. By the 1950s, he was allowed to sign his work. He drew many covers, did about half the comic book stories (with Al Plastino imitating him on quite a few others) and also did the newspaper strip until the late '60s. Editor-in-Chief Mort Weisinger, a man not especially well-liked by many of his employees, was in charge of all things Superman. Boring told me that one day Weisinger called him into his office and fired him on the spot. A bit later, Stan Kaye, who was his primary inker, was also let go. Boring was one of the artists who initiated the trend for superheroes who looked like they worked out at the gym and certainly did a lot of weight lifting. Jim Steranko praised him in his history of comic books.

Boring stayed on and became the chief artist on Superman. By the 1950s, he was allowed to sign his work. He drew many covers, did about half the comic book stories (with Al Plastino imitating him on quite a few others) and also did the newspaper strip until the late '60s. Editor-in-Chief Mort Weisinger, a man not especially well-liked by many of his employees, was in charge of all things Superman. Boring told me that one day Weisinger called him into his office and fired him on the spot. A bit later, Stan Kaye, who was his primary inker, was also let go. Boring was one of the artists who initiated the trend for superheroes who looked like they worked out at the gym and certainly did a lot of weight lifting. Jim Steranko praised him in his history of comic books.

Boring then became a non-person as far as the then administration of DC was concerned. A hardcover book, Superman: From the 30s to the 70s, was published in 1971 and his well-known hands-on-hips portrait of Superman was used on the cover. There were also over eighty pages of his work in the compilation. But he was not mentioned at all, however, and neither were Siegel and Shuster. A rather strange omission. At a lunch with some Connecticut cartoonist, I brought my copy of the book to show Wayne. He never even knew about it. He went through it, talking about the cartoonists whose work was also included—Paul Cassidy, Leo Nowak and John Sikela. That evening he phoned to say that he was very upset about the fact that he got no credit for his work and nothing in the way of compensation. I suggested he might want to talk to a lawyer.

Eventually he found out that because of the way things were during his days with DC, he was basically an artist-for-hire and had no rights. A while later he did some work for Marvel, chiefly on their Captain Marvel. His last cartooning work was assisting on such newspaper strips as Prince Valiant and Rip Kirby. He drew, for a relatively short time, Davy Jones for the United Feature syndicate.

He and his wife moved to Florida and he gave up comics and did some painting. For a new DC administration, he drew Superman twice more, once for an anniversary issue. Then, for the last time, in 1985. Roy Thomas, who was then editing for DC Comics, was renovating the Secret Origins comic book. Instead of simply reprinting origin stories he decided to commission new tellings of the "classic" tales. This would made for a “new, exciting, collectible item.” He chose Jerry Ordway to do the inking. A fellow with a great fondness for the artists of the Golden Age, Thomas hired Wayne Boring to do the pencils.

The origin of Superman from Action #1 was redone and expanded into 21 pages. The new, improved magazine was renumbered No.1. It had a cover by Ordway and Roy Thomas, Wayne Boring and Jerry Ordway got a credit on the cover. Boring proved that he could still draw Superman and Clark Kent just about as well as ever. But he was earning his living working as a security guard. “This is a mild job I’ve got,” he said in a letter. “And they pay me well.” He died in 1986.

Fresh out of World War II service, Curt Swan got himself hired by DC Comics in 1945. One of his first assignment was drawing The Boy Commandos, the creation of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, a hard act to follow. Swann’s early efforts were a bit shaky and ill at ease. But he was a good example of the learning-by-doing approach and he continued to improve. “I was getting $18 a page. It didn’t sound bad at first until I discovered how long it took me to draw a single page,” he said in this unpublished autobiography. By starting to handle only pencils and speeding up his pace, he was able to earn a salary of $10,000 a year. Not bad at the time. By 1948, Swan was drawing Tommy Tomorrow, a science fiction adventure. Eventually Tommy was a colonel in an interplanetary law and order agency, sort of intergalactic commandos, called The Planeteers. A TV show with a similar attitude to space travel was Tom Corbett, Space Cadet, which began in 1950. Tommy began roving the spaceways in Action Comics #127 and Swan remained onboard until #171. Over forty issues of six and then eight pages.

What solidified his career and boosted his reputation was getting the job of drawing DC’s major star, Superman himself. He began penciling the feature in the middle 1950s and stayed with the Man of Steel for three decades. His favorite inker, and the best one he ever worked with, was the gifted and amiable Murphy Anderson. He seemed to inspire Swan to keep improving. Comics historians Will Jacobs and Gerard Jones say, “The art was the best of Superman’s long career. With Anderson’s precise finishing, Swan was able to display his new facility for bold, dynamic ‘modern’ layouts.”

The main roadblock on his road to happiness was the same one that caused Wayne Boring such a bumpy trip. Namely, Mort Weisinger, who was still in charge of Superman. Swan began getting migraine headaches, palpitations and spells of depression because of the editor’s tirades and criticisms. But instead of giving up, he stood up to Weisinger and wasn’t fired or forced to walk out, writer. All in all Curt Swan penciled nearly 600 Superman stories for Action and for The Adventures of Superman another 200 or more. There were also many covers for both the magazines.

In 1986 artist/writer John Byrne, a longtime Marvel hotshot, who had been lured over to DC, in hopes he could do for the ailing Superman what he had done for Marvel’s massive sales hits The Uncanny X-Men and The Fantastic Four. Swan was given a pink slip as far as Superman was concerned. Wayne Boring’s advice to him at the time was, “Just hang in there and don’t take any shit.” A typical reaction to his ouster was from a critic, who said, “They closed the door on the creator that had defined their whole line. With no thanks, no pomp nor circumstance, DC simply relieved Curt of his artistic duties on Superman.”

In the early spring of 1988, DC decided to pep up Action’s sales by converting it into a weekly. The maiden issue of Action Comics Weekly was dated May 4 1988 and had continued adventures of such characters as Green Lantern, Black Canary, Secret Six and Blackhawk. Swan, who was still doing odd jobs for other DC titles, was asked to contribute 2 pages of Superman per issue. These appeared in the centerfold and were actually laid out as Sunday pages. In that autobiography, Curt Swan commented on his career. “It still surprises me sometimes when I think about it. It was never something I set out to do. It just happened the way a lot of good things do in fact.” He was found dead in his studio a victim of a sudden heart attack, surrounded by comic books, on June 17, 1996.

When Wayne Boring commenced working in comic books, there were but a handful of a titles and a handful of publishers. By Curt Swan’s time comic books were big business. Although the lion’s share of the profits were going to the publishers.

Jerry Ordway grew up in an era when comics fandom was flourishing, comics conventions, large and small, were rampant across the country and the profession of comic book artist was considered so legitimate that you could major in it at some colleges. As a teenager, the Marvel superheroes were Ordway’s favorites. He was inventing and drawing his own superheroes and his work began appearing in fanzines. His own fanzine, entitled Okay Comics, a bimonthly, started in 1975. He segued into real comic books in 1980, after he showed samples of his work to a DC representative at the Chicago comic-con that year. That summer he inked stories for such titles as Mystery in Space and Weird War Tales. Also for All-Star Squadron, a title that revived some of the heroes from the Golden Age All-Star Comics and added Plastic Man, who didn’t belong to DC in the '40s.

Editor Roy Thomas, whose nostalgic bent was mentioned earlier, brought the gang of 40s heroes back from the dead and scripted the stories that Ordway drew. “It was a great learning experience for me, as I had to draw a lot more stuff than the average starting artist is asked to do,” he’s said. “I built models of Japanese Zeroes, as well as US warplanes, and even an aircraft carrier.” In the next few years, with Thomas, co-created Infinity, Inc, that depicted another justice-seeking over-the-hill-hero groups that included Hourman, Star-Spangled Kid, Starman and Dr. Midnite.

The 1986 ousting of Curt Swan, brought Ordway onto the Superman team, as a writer at first and then as an artist. The original Captain Marvel, the red-clad superhero, the one DC sued Fawcett for plagiarism over, was now being published by DC under the title Shazam! Original co-creator C.C. Beck drew the adventures for a while, but decided that none of the writers given the job were even half as good as Otto Binder, who’d supplied most of the Big Red Cheese’s scripts during his Golden Age run. The title expired in 1994. Ordway, who’d been lobbying for a revival for some time, finally got his way and was assigned the writing and drawing of a graphic novel---The Power of Shazam! (There’s that exclamation again.) The success of that led to a monthly comic book of the same title that he wrote and drew. That lasted until the end of the 90s. His scripting and drawing was now among the best in the business.

Among the later projects he was involved with were Wonder Woman, The Brave and the Bold, The Justice Society of America and Black Adam, a one-shot using a notorious Captain Marvel villain. As the second decade of the 21st Decade progressed, Ordway began to sense that he might be going the way of Wayne Boring and Curt Swan. He posted a letter online titled Life Over Fifty. It began “I want to list a few things that have been bothering me lately.” After listing some of his idols---Jack Kirby, John Buscema, Gil Kane, John Romita, Don Heck and Gray Morrow, he pointed out that most, if not all, worked steadily into their 70s or until they passed away. Ordway reminded that he had worked on some of the company’s lucrative properties, particularly the comic book adaptation of the 1989 Batman movie that was “one of the best-selling comic book movie adaptions ever.” He went on to say, I seemed to suffer from the canceling of Shazam and being fired from Superman books I had been invited to do again.”

He went to Marvel for a few years to work on The Avengers, Captain America and Thor. When he worked again for DC, he worked on Wonder Woman and then fell into being a “fill-in” artist, jumping from title to title whenever the regular artists were behind deadlines or unavailable. “After 9 years of being the guy who was thrown at deadline material, I was no closer to regular work nor was I treated as a valued employee.”

He ended up his letter by saying, “I am thrilled to be remembered, and respected in the comic book community…I still feel vital, and still want to be at the table, I’m not retired, I’m not financially independent, I’m a working guy with a family, working for a flat page rate that hasn’t changed substantially since 1995… My work is still sharp, my mind is still full of stories to tell, and I’m still willing to work all hours to meet my deadlines. I don’t want to be a nostalgia act, remembered for what I did 20, 30 years ago.”

A couple of hundred responses came in responding to Ordway’s situation. Among the less sympathetic was this one, and I quote some lines, “I love Ordway and wish he were working on more prominent books, but I also accept that his style is resolutely old-fashioned (for better or worse) like Perez, Dan Jurgens, etc….I also understand why it doesn’t appeal to teenagers and twenty-somethings.” Could it be that some of the younger editors at DC had similar thoughts?

While working on this piece, I visited my local comics shop to browse its large selection of current comic book titles. I came across only two magazines that had his name on the cover—the first two, and only, issues of the briefly revived Infinity Inc. for which he provided just the scripts.