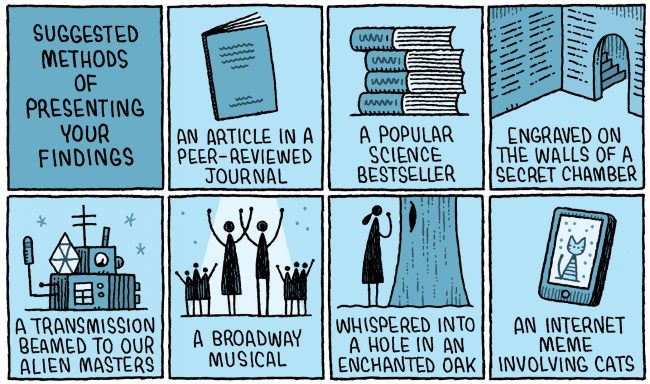

Tom Gauld’s transformation of the humble stick figure is perhaps the most impressive sleight of hand you will witness. Gauld’s iconic style, visual clarity, and playful incongruities lend his narratives with a depth of insight and feeling that perhaps unanticipated from a simple approach. This approach, however, has become a signature of Gauld’s illustration work (The New Yorker), strip work (The Guardian and New Scientist Magazine), and original graphic novels (Goliath and Mooncop). Gauld seems to delight in overturning generic tropes, character archetypes, and reader expectations in his work. His diagrammatic cartooning adds layers of meaning to even single-panel narratives and injects the ordinary with a bit of the fantastic. Charming and unassuming, there’s something for every reader to admire in Gauld’s work. Gauld takes a moment away from the tight deadlines of weekly comic strip creation to talk about his artistic development, his home library, and his latest book with Drawn and Quarterly, Department of Mind-Blowing Theories. Gauld also reflects on comics as artistic objects, how different formats impact visual storytelling, how political themes infiltrate his work or don’t, and the reader’s role in creating meaning.

The following interview was conducted in July 2020. This interview has been edited and condensed from its original form for the purposes of clarity.

Portrait of an Artist

Irene Velentzas: The first thing I’m curious to know is: What were you like as a child?

Tom Gauld: I think I was a pretty normal kid in lots of ways. I lived in the countryside, I liked playing outside in the woods with my friends, but I did love to draw. I just spent hours filling notebooks and papers. I make comics now and that came definitely from drawing rather than writing. I made stories, but for me, it was always more about drawing the pictures. I was quiet, but not exceptionally so, and I liked to read, but probably not as much as you’d imagine from somebody who now makes a living doing a lot of literary cartoons.

I was definitely picturing somebody who would doodle a lot of monsters in battle as a child.

Yes. I was lucky when I was in primary school I used to draw in the margins of all my books, and my teacher said to me one day: ‘I’ll give you an extra book and you can just draw in that when you’re finished your work, and as long as you’re finishing the work, you can fill that with as many doodles as you want.’ From about the age of seven or eight, I had a sketch book, which I was allowed to use. Because I was generally keeping up with the work, it didn’t seem to matter that I was doodling at the same time, in fact sometimes it probably helped my thinking process. It was very kind of [my teacher] Mrs. Horrocks to give me that when I was young.

A lot of your comics focus on time travel. So, tell me, if you could travel to any when or where, past or future, when/where would you go to, and what would you do once you got there?

There are a lot of places. It would be kind of crazy just to go to one. But, if I could just really go to one, I’d probably go to the Medieval Times. I think going back to London in the time of Henry VIII would be so totally fascinating. But also, I’ve always loved P.G. Wodehouse’s books – funny books about upper class life in 20s and 30s London. So I’d [also] want to wander around there. In both cases, as long as I was a very rich important person, or I could bring back lots of diamonds and sell them, I’d go there.

If we transposed “My Library” (Baking with Kafka p.16) onto your home library what’s one book that would fall under each of the following categories?

Read: The Fields Beneath: The History of One London Village [by Gillian Tindall], it’s more or less about the part of London I live in. Weirdly, I was listening to a podcast interview with Dylan Horrocks, a New Zealand cartoonist whose work I like a lot, and he was talking about this book. I just thought it was a weird coincidence that I was listening to the podcast because I like his work, and there he is in New Zealand, reading a book about the history of the area that I live in. So, on his recommendation, I read it. A bit like the time-travel question, it’s fascinating somewhere as old as London, to walk down the streets and imagine the cow sheds that would have been there 200 years ago, so I really enjoyed that book.

Intending to Read: Well, the book that’s permanently on my “Intending to Read” pile is Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace. I think I bought it 20 years ago, and I tried starting it twice. Both times, I didn’t hate it, but somehow lost interest and put it down. I think one day I will read it.

Half Read: More often, the books I’ve half-read are books of short stories, because I love reading short stories, but I don’t like feeling that you have to go from one story to the next one and sometimes, I think the best way to read short stories of comics and of [prose], is in issues like The New Yorker where the story stands alone. I love John Cheever’s short stories, but if you read too many, they all just kind of blend into one big story, which is kind of interesting, but loses the individual greatness of each one. So, I’ve got lots of books of short stories where I’ve read two of them; I will come back and read those others, but I haven’t gotten around to them.

Pretend I’ve Read: Well, with a cartoon like this, what I’m often doing is picking a bad quality of myself or something you can see as negative, and kind of turning it up to 12, or 20, or 100, to make it funny. So, even though I am as vain as the next person, I don’t think there’s any books I regularly pretend to have read. But I have made cartoons about both Ulysses and Moby Dick, and I’ve read neither of them. I guess that is a sort of pretending to have read a book.

Saving for when I have more time: I think both Ulysses and Moby Dick I would one day like to read. I had the same thing [with] a handful of cartoons [I wrote] about Jane Austen [which] I based on the general cultural version of Jane Austen, having only seen television programs and having never read any of her books. Then, I started to feel bad, so I read a couple and they’re brilliant. Maybe, Ulysses and Moby Dick will turn out to be brilliant and inspire lots of new cartoons.

Will never read again: Well I would say that the only book I have on my shelf is The Complete Works of Shakespeare, as one rather elegant big volume, it’s so large [that] I don’t think I’m ever going to read it all. I do dip into it sometimes and look things up, and flick through looking for inspiration. But I’d be very surprised if that book is ever read cover to cover.

Purely for show – well this might also be The Complete Works of Shakespeare: Well, I am a bit of a sucker for a beautifully designed book…But I would say none of my books are there purely for show, that’s the particularly vain cartoon version of me; but I’ve probably got about 20 volumes of McSweeney’s literary magazine, and I have read some brilliant things in there, but it was the beauty of the design [that] suckered me into buying the complete set.

So, you can judge a book by it’s cover, is what you’re saying.

I think when it comes to comics and cartooning, the design of the object of the book, and the cover, does generally tie in more than with fiction where you can read a book with a terrible cover and it doesn’t badly [affect the story]. In fact, with fiction you can read a badly printed, in a terrible font, and it still pretty much works. Whereas with a comic book, the object of the book is tied to the story in ways that fiction isn’t. That’s one of the things I love about comic books. You get to write a story, but you also get to design an object and make a thing as well.

Read, but can’t remember a single thing about it: I’ve got lots of Graham Greene books. I went through stage in my late teens, thinking he was great – which he probably is – but I haven’t reread any of them for years. Some of them, I can’t imagine as an 18-year-old, I was getting very much out of. So, I don’t recall a lot about those books, but I’m looking forward to revisiting them at some point. [Also,] when you have to read something – there are some books I’ve drawn covers for where I’ve read fishing for interesting stuff to draw on the cover – reading them was work rather than pleasure. Those ones slip away as well.

Wish I hadn’t read: That one came to me quite easy. There’s a book called Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett. Weirdly, the BBC did a list of The Greatest Books of All Time, and I think it was voted for by the public and it came out on top. So, I thought, ‘Well, if everybody thinks it’s great, I should give it a try,’ and it was so dull and boring – and not even boring like something that’s good for you. So yeah, I think I got about three quarters of the way through it and gave up on that.

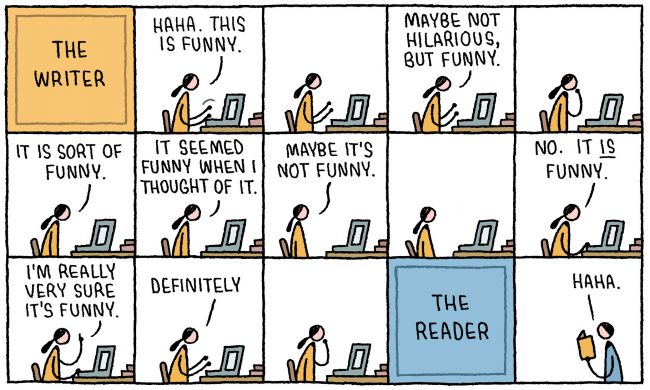

Do you have any of the writerly misgivings you depict in your comics when it comes to creating and developing your own ideas?

Yeah. I think that most of the feelings the characters in the cartoons have some element in my personality just turned up to 11. So, I’m not constantly wracked with misgivings, but I’m always trying to think carefully; especially with jokes, you don’t want them to misfire or be misunderstood. Creating anything, I think all art is about thinking more carefully about what you’re doing that you do in everyday life and making something more carefully prepared. So, it is a sort of recipe for misgivings and overthinking and perfectionism. All of those things are sort of necessary – you kind of need to be aiming for perfection, but you also need to be forgiving that you’re not going to make it perfect. So, there’s a lot of crazy stuff that goes on in your head when you’re trying to make art.

Tell me about your studies and artistic focus at Edinburgh College of Art and the Royal College of Art. What was your main focus in school and at what point did you begin to develop the iconic style readers know from your strips and original graphic novels?

Well, I went to art school, because as I was saying, I love drawing. In Edinburgh you do a foundation year [studying] all the arts and general drawing classes. Then you specialize. I knew by the end of the first year that I either wanted to study illustration or animation. I thought I wanted to tell stories with pictures either children’s books, or illustrating other people’s things, or maybe drawing comics. At the time, I didn’t feel confident in my own writing. Animation, I realized, just took too long. This was in 1996-1997 – computers were pretty new for animation, so it was even slower then than it is now. I wasn’t sure enough that I wanted to do it to commit to three years making a film. So, I did illustration. The head of department, Jonathan Gibbs encouraged my visual storytelling. He wasn’t one of those tutors who some of my contemporaries ran across who disapproved of comics. He was entirely encouraging and showed me Edward Gorey’s work, which was a big influence on my work, and I remember showing him Chris Ware’s work, which he thought was wonderful.

By the end of Edinburgh, I realized that much as I liked doing illustrations of other people’s work – which I still do – telling my own stories with comics and pictures was what most fascinated me. [That] was why I applied to the Royal College of Art; you’re encouraged to follow your own path. I told them that I was interested in visual storytelling and the head of the department is a guy called Andrzej Klimowski who – at the time hadn’t written any comics though he has written some now – had written a wordless graphic novel. This [was] in 1999. In Britain, there weren’t that many cartoonists teaching in art schools – so it was good to go somewhere with someone who was interested in [visual] storytelling.

I was [also] encouraged by my contemporaries. I shared a studio with Simone Lia, who I worked with to make our first comics. [We] collaborated to publish a collection together. So, between Simone and the tutors and the other students, I had a nice helpful audience and that’s where I started. That’s where I first started drawing very simple stickman-like illustrations.

When you first started creating comics, was it challenging to find a niche or appreciation for your unique voice in the industry? Did you have any setbacks as a new creator, and if so, how did you overcome them?

We were pretty lucky I think, Simone and I. [There] was a bit of a lull [in British comics] around 2000. We published our first book in 2001 and didn’t feel like British comics was terribly alive at the point. There were some really good people making comics, but not many. There wasn’t a lot of a scene of young cartoonists. So, it did feel like there was a kind of empty stage for us to come out onto. Our [self-published] comics did pretty well in the shops, [but] I didn’t expect to make a living as a cartoonist. I was very happy making a living as an illustrator and treating cartooning very much as a kind of hobby that made a little bit of money, and where I could express myself.

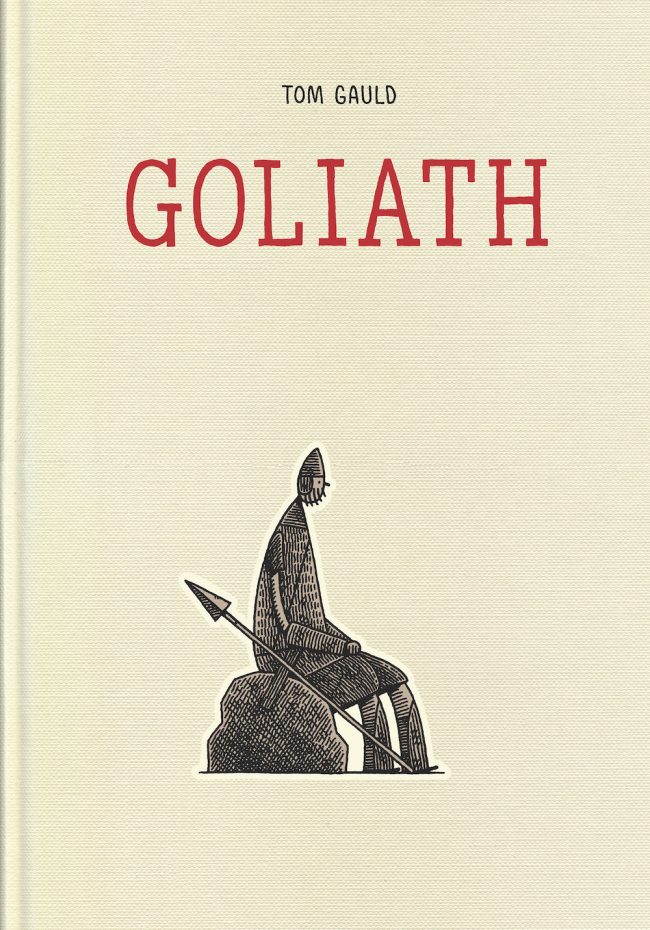

The only real setback I really felt I had in my career, was a kind of writer’s block in terms of trying to write a graphic novel – which I knew after a while is what I ought to do. [It’s also] what the market wants from you, it doesn’t want mini comics. Well, it does in a way. It’s fun to do mini comics, but a graphic novel is a way to get to a larger audience. Eventually, I managed to write my first short graphic novel, Goliath.

I really love getting a comic from you each day. It’s something I look forward to. I know it’s going to brighten my day. It’s one of the things that’s interesting about the comics industry– this push pull between strips and OGNs. But to circle around to an earlier point: you spoke about how sometimes it’s too much reading one short story after another, especially if they blend together over a longer narrative. So, to put that idea back to you, would it be worthwhile to develop a set of characters that started in strip and became a longer narrative over time? Or, do you feel that getting to do these one-shot strips allows you to be creative in any way you choose at any time, rather than having to stick to the same type of narrative arc?

The good thing that happened after I did Goliath, is that I felt like that [writing] block was gone. I had done a graphic novel. I do enjoy writing short stories, and I do enjoy writing the weekly short jokes; they’re more pleasurable and easier than writing longer stories. I’ve never been able to write characters who reappear in multiple stories. I don’t know why. It would make it a lot easier each week when I came back to my drawing board and the deadline was coming, if I had something to start from. I think maybe I’m more interested in ideas than characters in a way. The cartoons often start with an idea and the characters come second. So, that may be the reason.

Visualization and Narrative Process

Despite the visual simplicity of your storyworlds and character creation, your works produce impactful emotional responses, without even relying on such typical communicative staples as facial expression. What storytelling techniques do you use to create the greatest emotional impact?

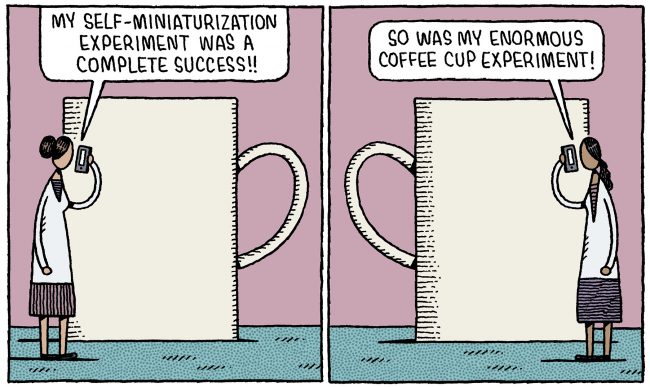

I read something quite early on saying how a simple cartoon face – I think the example used was Tintin’s face, which is just two dots a nose and a mouth – allows the reader to project their own emotions onto simple iconic face [Note: This idea can be found in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics]. So, [Tintin] will be standing in a very realistic world and yet somehow, we’re willing to accept this very simple face. It’s easier to read the emotions on that simple face than a beautifully rendered, realistic drawing. I like that idea, that with comics you can leave gaps for the readers to project into. I think the emotions that readers project into a gap are almost better than what you could put in there, as a writer. Obviously, you have to nudge them, persuade them, to put the right things into that hole. I like the idea of not saying things, and yet having them happen in the reader’s mind.

So, one reason is that – the technical reason. The second reason is that I can’t seem to draw faces very well or in a way that satisfies me to draw that character’s face 150 times in a book or even a handful of times in a short strip. When I started, I was drawing these little stick figures, partly because I was learning. I thought ‘It’s so hard to learn to draw comics and to tell stories.’ So, I thought, ‘I’ll start to draw very simply like this, and then, perhaps later, I’ll improve the drawing in some way or make it more complicated.’ Then I just found that the simple figures worked. Having a stick figure, someone can imagine ‘That’s me.’ You’re not saying, ‘Oh, it’s a blond person with white skin and blue eyes.’ It’s this more universal character, which I think can elicit more sympathy from the reader.

As you are well-known for both your strip work and your original graphic novels, tell me a little bit about the creative processes behind each of these types of narrative: Is your approach to each type of narrative similar or different? How? Why?

Well, in a way, it’s exactly the same process, which is: me sitting with my sketch book and doodling in there until an idea comes together and is interesting enough that I feel it’s worth taking further. Then I’ll keep working on it in my notebook until it’s pretty much ready as an idea. The easy thing about the short cartoons is that you can do that in a notebook, you can come up with an idea and in an hour, or two hours, or three hours – with enough coffee – something will come together. Then, I can move to the drawing board, and in a more careful way, make a drawing of this idea that works for the space in a newspaper or the magazine. I quite enjoy that process for the weekly cartoons. I like the fact that there’s a deadline, and I’ve really just got one day. If I don’t have a great idea, I have to take a mediocre idea, polish it as much as I can, and make it as presentable as I can. I like the finiteness of that, and the fact that if it’s not great then the next week I can just try to make it better and that sort of suits my personality in some way.

[With] graphic novels, the problem is that first step of coming up with an idea. I think a lot of the work is persuading yourself that the idea is worth doing. You need to persuade yourself to keep going and make it better, but it’s a sort of Catch-22: It’s not going to be good because you haven’t worked on it yet, but you have to sort of trick yourself into working on it long enough that it starts becoming good. Eventually, it turns into a snowball and keeps going, because then it’s getting good and it’s easy to work on. But, that first step of coming up with an idea and talking yourself into it, is the thing I find hard. With a graphic novel, you’re thinking to yourself ‘I’m going to work on this for a year, and it’s going to be a book that people are going to pay for and read for half an hour, an hour, or two hours.’ So, it’s harder to get started. Whereas, with the short comics, I say to myself, ‘It’s in a newspaper, so if someone doesn’t like it, they can read a different bit of the newspaper.’ [That’s] kind of easier.

Tell me about the different types of pacing you set up in your strip work versus in your original graphic novel works like Goliath and Mooncop. How do you approach the pacing of your narratives in each of these formats and use pacing to the story’s best advantage?

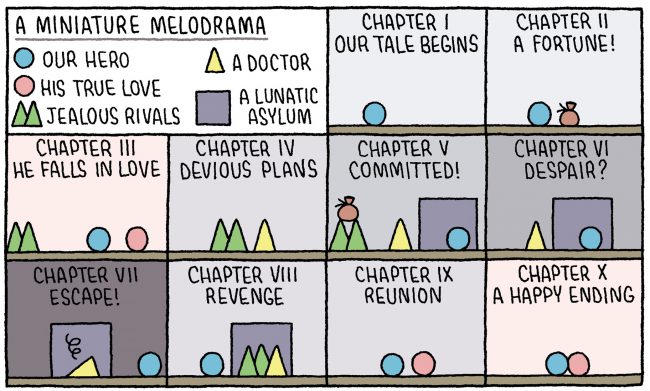

Pacing and laying out images on the page is almost my favourite part of being a cartoonist. If I really had to, if someone handed me a pile of drawings, I could enjoy laying out somebody else’s drawings in a comic and telling someone else’s stories. It’s almost like that’s the most fun bit. I guess it’s another reason why I work with quite simple drawings, it makes it easier to play around with the pacing. The great thing about a graphic novel, as opposed to the short cartoons, is just having more space. If you want to draw something out over ten pages, you can. Or, if you want to compress a gigantic event into one panel, you can do that. That’s one of the things that I think comics are quite brilliant at. You can play with time in a way which the reader isn’t trapped in it. If you’re watching a movie and things are going slowly, you kind of have to sit there, and things are going slowly for you. Whereas, in a comic, where your eyes can move over the page at your own pace, you can almost depict boredom in a way that isn’t boring and lots of other interesting things. So, I think one of the most fascinating aspects of comics for me is laying out things on a page.

That’s interesting. Yeah, there’s a lot of breathing room in your OGNs, which is something I really, really like. It just gets to sit with you long enough for you to fill in all of these gaps as you’ve been talking about. That’s a lot of where that question comes from.

And with the short cartoons it can be a bit frustrating sometimes, because I have these rather small spaces to fill. There are some jokes where I would have loved to have a pause, a silent panel, just before the punch line or after the punchline – but that’s also one of the interesting things about having a space that you play with differently every week is the restrictions of the shape is part of the interest.

Yes, constraints do seem to lead to their own form of creativity, for example, much of your work has a diagrammatic quality to it; you often use legends, symbols, maps, numbered lists, giving your comics an extra element that requires deciphering. Tell us about creating diagrammatic forms of visualization in your comics and their appeal.

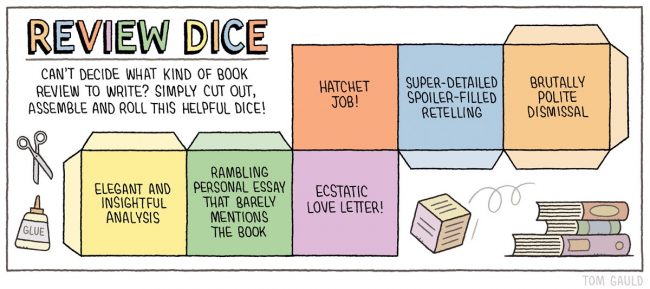

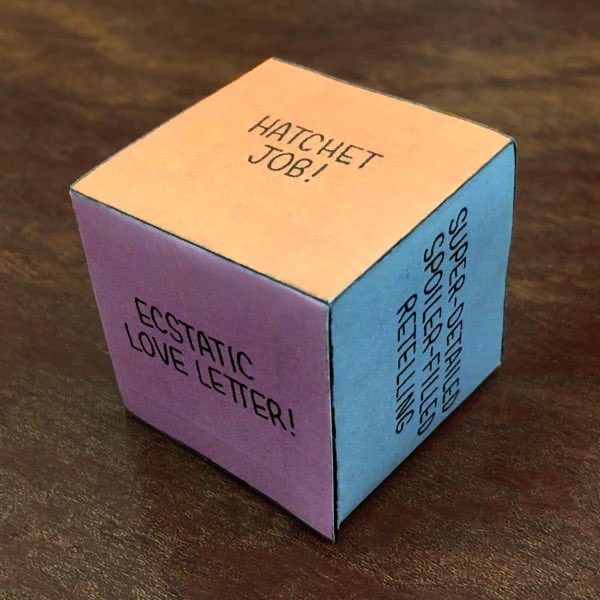

I love doing them and I think there’s a nerdy part of me that likes books with puzzles in them, and books like The Hobbit with a map or a message written in runes. I like those kind of puzzle aspects. I’m doing these cartoons every single week and I don’t want every week to be a four-panel comic strip with a punchline on the fourth panel. Sometimes it is, and that’s fun to do, but at other times, thinking: ‘Oh, it would be fun to do a word search or a diagram.’ The form can inspire the cartoons as well. Sometimes, what might be a very simple idea, as you try to figure out how to make it work, correctly, as a maze or a something else, it gains another level which makes it more interesting. I like making those nerdy diagrams. I kind of pride myself on the fact that they work. I did a cartoon for The Guardian, which was a fold up dice that you could roll to decide what sort of book review to write. I did this last week. I actually made it because, even though I knew nobody was going to cut it out of The Guardian, I wanted it to be workable. And of course, when I posed it on Twitter, someone said “I think you’ll find this doesn’t fold up into a dice.” So, I could immediately send that person a photograph showing that they could! So, I like that nerdy technical aspect of making sure that the things work, even though I know nobody’s ever going to check.

It is ‘art as object’ again, and I definitely understand that. The more you can play with what the form is, it goes form a 2D strip to a 3D object you can have in space. On a very small level, not like a book, but from a page. It’s a transformation.

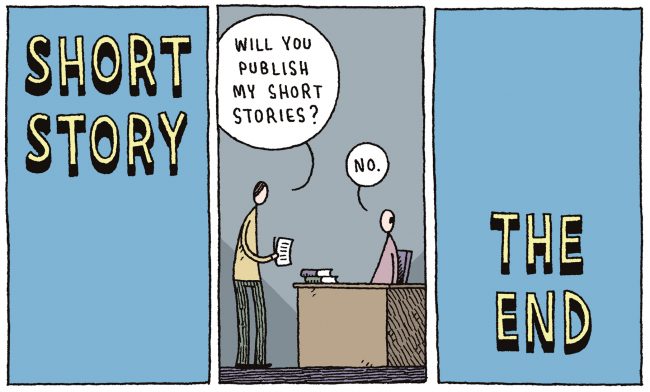

The strip, “Short Story” in You’re All Just Jealous of My Jetpack, reminds me of Ernest Hemingway’s “Six Word Memoir.” With this example in mind, I’d like to ask you: What exactly do you think constitutes “a story” and how do you think the comics form is changing the idea of what a story is or can be?

Literature has these very formal ideas, doesn’t it? They’ll talk about a long short story, or a short novella, or a novel, and it’s all about word counts and about formal ideas that we don’t have in comics. You don’t really have a panel count and ‘graphic novel’ is sort of a useless term. Even the fact that when you make a comic you have to think about, ‘Will this be a square book or a tall book?’ The physical form is much more present. Very few prose writers are going to be thinking about things like that on day one of making a project. So, I think comics open up the idea of what a story can be and that’s [why] in my very short comedy comics, a diagram can be a story. I don’t want to get into arguing semantics, but in those short cartoons I’m trying to tell a story with a diagram or tell a story with a fold up dice. I also like to set these silly rules for myself for as long as they work, for one single cartoon or for a story – but they’re not [hard] rules – as soon as they don’t work, I throw them away. So, my comics are quite formal, but I don’t have many ideas about form that go outside of those individual stories.

Thematic Considerations

In this same vein, I find your comic strip, “Once There Was An Incomplete Crossword,” Jetpack, p. 52, to be quite an sharp reflection of cultural ideologies that are placed on art’s definition and value, so I’d like to ask: What is art? What constitutes good art? What constitutes valuable art? Moreover, are these questions completely pointless?

When I started making cartoons for The Guardian, they used to first appear on the letters page, and the cartoon had to relate to one of the letters on the page. So, I think that one was something to do with crosswords. I don’t really know anything about crosswords, but I do like fairy tales, so I thought it would be funny to do an Ugly Duckling type story with a crossword. Again, there’s a deadline, and there’s only an afternoon to do it, so I don’t overthink it. It’s just ‘Oh that works’ and ‘I need to get on with it.’ So, there’s less thinking behind the cartoon than there might appear. In a way, I don’t worry myself about whether or not [something’s ‘art’]. I think the question of whether or not something’s art is important if you run an art gallery and you have to decide what goes into it. But I think, aside from that, it’s not that important. I don’t think about it. Having been to art school, there was a lot of talk about it then and I’ve sort of realized that it’s not a question I have any interest in solving.

I think what your comic brings to the forefront, in that regard, is really that it’s all a matter of perspective. Anything can become art based on who contextualizes it.

I suppose for me, it matters much more whether you’re interested by it, whether you’re moved by it, whether you are offended by it, or like it. Those are all much more important and interesting questions than whether or not it’s art. I don’t care if cartoons are considered art or not, and I don’t think it’s helpful when cartoonists think it would be better if we were considered more like fine art. Cartoons and comics are what they are and we should just, I think, try to make them as good as they can be and not go looking for approval from the fine arts.

The Art of Politics/The Politics of Art

In light of the previous question regarding the value of art, I’d like to bend the conversation towards some of the underlying political themes in your comic strips.

In our current cultural situation, we are seeing public sculptures of historical figures being defaced during political protests or taken down by governmental and institutional bodies. What do you think should happen to these artworks when a society has found them detrimental to their culture or no longer representative of their culture?

I haven’t given it a huge amount of thought, but I have heard people say that the correct place for these things is in a museum where they become an artifact, where we can explain what they mean. Somewhere they are not presented as ‘Hey, this is our culture, and this is what’s important to us,’ [but as] ‘This is what our history was, and this meant something to these people in the past.’ I think destroying these things isn’t necessary, I think you can contextualize them properly in a museum and explain both sides there in a way that you can’t with just a big statue in a park.

I tend to agree, I think providing context is very important for these historical figures.

The thing is, in London, for example, there are statues everywhere and I would guess 90% of these men – and they almost all are men – have something unpleasant in their life. They were important people centuries ago – and important men centuries ago generally did things that [by today’s standard] we think are awful. I guess on some level you do have to balance out how awful does somebody have to be [to be removed from public spaces]? That [balance] is tricky and it isn’t for me to decide – you’d need some kind of committee to figure these things out.

Sometimes, I’m amazed at how you sum up a relevant political issue like gender equality so succinctly but also so humorously within the space of a panel or two. How do you manage visualizing political issues in a more nuanced way without resorting to outright political satire?

Well, I don’t make political satire at all. It doesn’t appeal to me. I can admire some of the – especially in Britain – political newspaper cartoonists [as] wonderful draughtsmen. But, I’m not that interested in their work and I certainly don’t have the type of personality where I could do that for a living, or where I’d be good at it. When [one of my] cartoons does go into the political world it usually sort of sidles in, in a sort of silly way. I’ll have some absurdity in there, or I’ll try to open it up to a more general human point than a kind of party-political or news-political sort of point. I’m wary of foisting my opinions on people. I think of those political cartoons that are labelled – you know, “The Politician, Riding The Bus of Change, Into Chasm of Recession.” I’m so wary of that, I’m so allergic to that idea, that I go it at a more oblique version. I’m often unsure exactly what I think and can’t necessarily put my point of view successfully across. So, I’m often saying ‘This is the world and it’s weird,’ rather than ‘This is the world and this is how we can fix it.”

Maybe that’s one of the aspects that makes your strips so pleasant and enjoyable.

Well, I do want to be pleasant and enjoyable. I’m a bit of a coward, I don’t want to get into arguments with people or even upset people. Most often the cartoons are teasing people I like: making fun of pretentious writers, who in the end, I actually respect. Rather than angry political cartoons aimed at politicians I hate, which I wouldn’t be good at.

Sciart vs. Artience

I wanted to talk a little bit about “Sciart” or “Artience” the blending of science and art together. You create weekly cartoons for The Guardian, which takes on a literary bent, and for New Scientist Magazine, which typically takes on scientific subject-matter. However, there is a fair amount of cross-over between artistic and scientific subject matter in sets of work, so I’d like to talk to you about the blending of both of these disciplines.

How do you think comics lends itself to the blending of artistic and scientific subject-matter?

Well, when I started making the weekly cartoons for New Scientist Magazine (NSM) I was worried that I didn’t know much about science. I mean, I’d been doing literary cartoons for years, I read for pleasure, and I’m interested in books, so I felt like I was on home turf. Even though I am relatively interested in science, I’m certainly not educated in it. I was concerned with the science cartoons that I’d be out of my depth. [I was concerned that] I wouldn’t ‘click’ with the scientific mindset and I wouldn’t know enough about it to make decent cartoons.

As I’ve done it, I’ve realized that actually, the scientific mindset isn’t as different from the artistic mindset as I thought. Sometimes, I’ll make a literary cartoon – and now, because I have followers on Twitter who are scientists – they’ll say ‘Ooh! It’s exactly the same for us in science!’ about being published, being disappointed with people’s reaction to your work, and having a block. All those things I guess are human things as much as writer/scientist things. They’re certainly for people who create things, which scientists, and writers, and artists do. So, I think I’ve realized that scientists aren’t this other species who I need to make work for and who will be furious at me for not understanding their discipline. I’m more like them than I thought.

And why are comics good [for blending artistic and scientific subjects]? I think in both cases, what’s nice about being in those magazines – in The Guardian Review and in New Scientist – is that most of it is very clever people being thoughtful and careful in what they write. It’s quite important stuff. Then, I have this sort of space where I’m allowed to be stupid. I have to be stupid in a way that isn’t insulting to them or insultingly stupid. So, I feel like my job is to be silly about intelligent subjects. It’s not for me to be as clever as those scientists or as well-informed on their subjects. But it’s also not to make a cartoon that totally understands what they do. So, I try and tease them respectfully. And sometimes, weirdly, that does involve spending an afternoon reading articles and trying to understand an aspect of science, in order to make a very silly joke about it, in a way that works. In both cases, it’s being an outsider who respects and understands their world enough to make jokes in it. So, the fact that comics are this other thing, sort of helps.

I think that comes back to this aspect of political cartooning we’ve been talking about. It takes a certain amount of respect not to caricaturize someone – not to portray the individual or situation badly – but rather, that everything can be reduced to its ironic or silly properties. If we don’t see that, we lose sight of the overall context that we’re in.

Yes, and I find that writers and scientists have a much better sense of humour about being teased than I might have thought before I did it. If I make a cartoon that makes fun of botanists, they enjoy that, rather than being furious at me. That’s been a nice thing I’ve learned over the years.

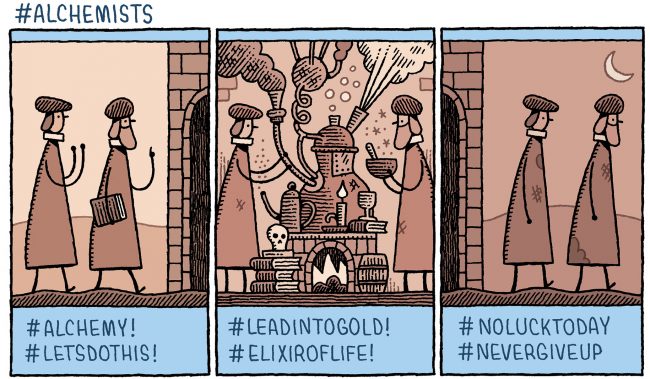

It feels like the anti-intellectualist, post-facts world is a contemporary problem, but, as your comic (“CharlesRobertDarwin Has Posted a Theory…” Dept. of Mind, p. 15) highlights, there has been pushback regarding scientific theories nearly since the beginning of scientific thought. What do you think accounts for this pushback and how does looking at science through an artistic lens, perhaps help or hinder our understanding of scientific knowledge?

In the end, the purpose of these cartoons is to be amusing. I don’t really go into them with much of an aim apart from that. One thing I’ve realized they can do, is they can humanize, and they can show that scientists aren’t sort of weird, emotionless robots who are doing weird science unconnected to the world or don’t care about anything. I think perhaps [these cartoons] can make people realize that [scientists] are humans who fail, fail by accident and want to do better, and aren’t living in an ivory tower. They’re people [who] are connected to the world. So, if there’s one thing I try to do, or hope cartoons can do, is stop that idea that science is unconnected to us, or unconnected to our lives, or that scientists are a different species. That’s something I think about occasionally.

So, Wizard vs. Scientist. Same Difference?

Kind of, yeah. I mean, that’s one of the ways to make things funny that I’ve found. I’ll think, ‘What is the opposite of this thing?’ and then put the two together in a cartoon. So, when I do literary cartoons, I often put scientists and robots and machines because that world felt very different from the creative world of writing. With the science cartoons, I think a fun opposite of science is magic, so I put in fairy tales, witches and wizards, and all these things that science has really disproved and is the opposite of. But, bringing them together in a cartoon can be kind of amusing and maybe pleasant.

Like, everything seems magical until you figure out what it is, and then it’s science?

But I think when you get too deeply into the science, and quantum science, and parallel universes you’re as much back into the world of magic or into anything I could understand really.

Technology and Literature

To push a little bit past science into the realm of technology. Do you think our relationship with books/literature is changing in the digital age, or has our relationship books/literature always included changing ways of accessing or interacting with literature?

I think it always has, but I certainly find for myself that there are a lot of things that distract me from sitting down and reading a book. Having a phone in my pocket that could be pinging. The idea that ‘Ooh, somebody could be liking one of my cartoons now!’ I might have an email, or this or that. I think the distraction from being able to sit down with a book is something that I have to fight against, and I imagine most people do. So, reading is, in a way, slightly under threat from all those other things demanding our attention. But I still think, there is nothing that beats – especially with a comic book – buying a beautiful comic book and putting your phone away. Not reading on a screen, but reading on a paper, this real-word object, which every part of has been carefully considered. So that commitment for a specific amount of time with this object is something I love about books on paper and comic books especially. I think we’ll hopefully be able to keep that magical aspect of reading.

Is it possible, that after all this time, the most revolutionary technology still remains the humble paper and pencil?

Well I still think it is. I still draw on paper with pencil. I love the fact those marks I make on the page can be printed almost exactly as they were on the page and find themselves all around the world and people reading them. I love that. I love that idea, even if you’re seeing it on a screen, you can see the little imperfections, the wobbles of my hand as I try to draw a straight line. I still love that; it stops me moving into working digitally. I still like that interaction with physical paper and pencil.

What kinds of questions or insights do you hope your work raises in readers and what’s coming up next for you?

In a way I try not to think too much about raising questions. My aim is usually to tell the story well. Sometimes, I look at it later and see then what I meant. Or, I do an interview about a book and I realize, ‘Oh that book does kind of say that.’ I usually try and tell an interesting story and all that other stuff seems to sort of happen while I’m focusing on the text.

And what’s next for me is I want to do a new graphic novel. Since I’ve finished the book of science cartoons, I’ve also finished a picture book for children. It was a fun experiment in using words and pictures to tell a different story in a different way and I really enjoyed that. But now, I’m itching to write another graphic novel.

I think my question about what insights does you work raise comes to mind because you have such a fresh perspective and your comics are very much about perspective. It’s always quite refreshing to read your long form and shorting strips. I feel that just encountering a different perspective is enough of an insight that readers can get from your work.

That is lovely to hear, and it is very nice when people respond to the comics well. Sometimes it’s surprising what somebody gets from it, and I realize that ‘Well, yes, that was working its way through there somewhere,’ but because I was trapped within the world of making the comic, I wasn’t seeing it from the outside. It’s sometimes rather pleasurable to send comics into the world and understand them better yourself later when you’re out of the panic and the flurry of making them.