Nothing appeals to artist François Boucq more than a marginal character. Angouleme's 1998 Grand Prize winner, Boucq is famous for his prolific output. But he's especially popular for creating Jerôme Moucherot. Moucherot, a character who sells insurance door-to-door, wears a leopardskin suit and sports a pen through his nose. His everyday world is, literally, a jungle.

"My taste in bandes dessinées," says his inventor, "is to create a kind of relief, a landscape whose forms are as varied as possible. I like to mix dwarves, bodybuilders, giant women… every kind of character. People call it cinematic but, to me, BD are the inverse of cinema. They're a set of still images the artist sets in motion – through his knowledge of rhythm, form and movement… It's like that moving line which carries along a symphony."

Boucq was talking about New York Cannibals, his fourth collaboration with the Bronx-born novelist Jerôme Charyn. The story, a sequel to the pair's Little Tulip (2014), bursts with those eccentrics the artist loves to draw. Its heroes are a gulag survivor called Pavel and his Japanese ward Azami, a female cop and bodybuilder. Their supporting cast includes a double amputee, an albino matron called Mama Paradise, a pitiless lesbian sorceress, a black transvestite pimp and a vampiric crew who sell blood taken from infants. The dark and steamy tale is flying out of bookstores.

By the time it appeared, though, Boucq was tackling a different challenge – a 'landscape' of characters he could not have imagined. At the request of Charlie Hebdo, he spent from last September 2 through December 16 inside a courtroom. He was drawing a terror trial: prosecutions for the murders at Charlie Hebdo, in Montrouge and at the Hyper Cacher ("Super Kosher") supermarket. Over three days, the events cost seventeen lives.

Their perpetrators – Chérif Kouachi, Saïd Kouachi and Amédy Coulibaly – were dead. But fourteen people were being judged as accomplices (three of whom, having fled, were tried in absentia). The charges varied from providing weapons and assisting terrorism to participation in a criminal network.

The court heard from survivors of the slaughter but also from neighbors, guards, hostages, police, bereaved families and bystanders. Not to mention the accused plus their own families, friends and associates.

This gamut of criminality lacked the glamour Boucq brings fiction. As he explained on French radio, "These were personalities from crime's lower levels. There was the guy with a smalltime bar, an old compulsive gambler, a long parade of drug dealers. But whether they knew it or not, all of them were involved in terrorism. What especially interested me was their rapport with religion… because their mentors bet on that. Yet the guys they were manipulating … They lacked the slightest relation to anything sacred. They were just people who had despaired of life, people who used crime to give themselves some standing."

The whole thing took place in Paris' High Court, at the heart of a new judicial complex. Opened in 2018, the Cité Judiciaire is one of the capital's few high-rise buildings. Just like the Centre Pompidou, it's a special project designed by Renzo Piano. Although it has landscaped roofs and a photovoltaic skin, the compound resembles a stack of big glass blocks. The space inside is open and airy and yet the High Court's tribunal lacks a single window. Unless they are at the bar, defendants are confined within a stark glass box.

Boucq had a partner for his daily trek to the site. This was Yannick Haenel, a writer, novelist and (since the 2015 attacks) a columnist at Charlie. Haenel is well-known to literary circles and, in addition to awards like the Prix Medicis, his work has several times given rise to polemics. But he had never set foot in a court.

In reports published every day in Charlie's website, Haenel and Boucq logged the proceedings in court. To create their rapid bulletins, Haenel rose at four a.m. and wrote until seven. The trial was expected to last two months but, with repeated delays from Covid, ran for 55 days. Under the title Janvier 2015, Boucq and Haenel have now produced a book about it.

It arose from a request. Charlie Hebdo editor Riss (Laurent Sourisseau) felt the trial deserved "a monument". Sourisseau had penned a book of his own. But, having survived the killings, he was also a witness. So he commissioned Boucq and Haenel.

Janvier 2015 turns out to be a compelling read. The trial's slow progress is captured and pondered, in page after page of dynamic, well-deployed drawings. Despite the enormous complexity of the case, text and images are so well-integrated that it's easy to follow. Details are given the space to resonate with one another even as, day by day, countless personalities emerge, take centre stage and then recede. Almost every snapshot, however, proves arresting.

Despite the unanimity of the verdicts – everyone is found guilty – the trial is hardly definitive. Yet the book transforms the incompleteness into something bigger. It's an eloquent creation and never remotely glib.

It's also the third exceptional work to arise from the trauma, the others being Catherine Meurisse's La Légèreté (2016) and Philippe Lançon's 2018 Le Lambeau ("The Shred of Skin"). Each of these is proof that art can hold out against horror and, to do so, each reshapes a conventional form. All vindicate the creativity Charlie nurtures – offbeat, improvised, impossible to encapsulate.

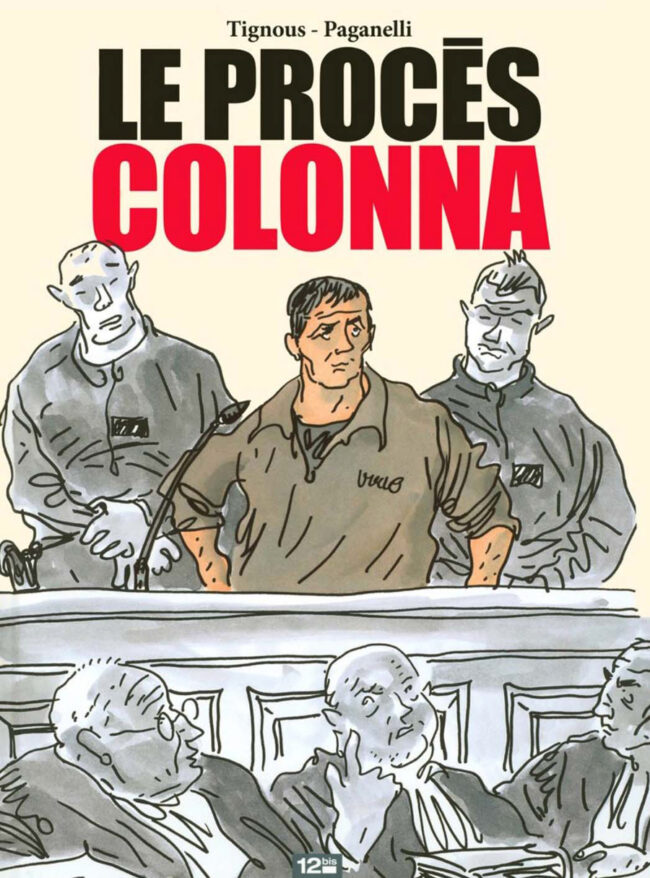

Charlie has a long history in the courtroom and many of its artists have made what are known in France as dessins d'audience. Two of the slain cartoonists, Cabu and Tignous (Bernard Verlhac), were especially famous for their judicial art. Riss too has long combined court art and court reporting. One of his bandes dessinées, Le Procès Papon, is a classic. It covers the 1998 trial that saw Vichy's Maurice Papon judged for crimes against humanity. On the verdict's 20th anniversary in 2018, it was re-issued.

Cabu began drawing in court in 1966, at the Mehdi Ben Barka trial. That trial featured French police among those charged with kidnapping and killing the Moroccan radical. Tignous' judicial art debuted with his own prosecution – at which right-wing Catholics fought Charlie's anti-clerical jibes. But Verlhac soon began to cover the trials of politicians, corrupt businessman, the National Front and the Church of Scientology. (He also investigated life behind bars and, at the time of his death, was at work on a BD about those in prison.) His best-known dessins d'audience appear in 2008's Le Procès Colonna. A record of Corsican militant Yvan Colonna's trial for murder, this received the Prix France Info – an award for each year's best graphic journalism.

Charlie's work in the courtroom is so respected that French Justice Minister Christiane Taubira spoke at Verlhac's funeral. Taubira (whose Charlie caricatures have been cited as proof the journal is racist) used her eulogy to name and praise each of the slain. "Policeman, Algerian, Jew, cartoonist," she said, "They were killed not for what they did but who they were."

As for Tignous, Taubira was unequivocal. "He is part of our great lineage of courtroom artists… the visual witnesses who gave us images such as those of [Paul] Renouard at the Dreyfus trial, those of Émile Zola on trial for publishing his J'Accuse.… Of course Tignous was impertinent and, clearly, he was funny. But he was also part of the Judicial Press Guild… He possessed a charmed pencil, one that managed to capture every emotion at a trial."

In other words, François Boucq's task was hardly small.

The terror trial was not Boucq's first time at court. In 2015, for Le Monde, the artist had drawn Dominique Strauss Kahn in the dock. (Charged with pimping, the former IMF chief was acquitted in only thirteen days.)

This trial, however, was radically different. It was closer to the landmarks Taubira had cited, historic moments that shook French society. The most important of these remain the (six) trials of the Dreyfus Affair, held between 1894 and 1906. Until the rise of Nazism, the 'Affair' was Europe's worst outbreak of anti-Semitism and Zola's 1898 trial for libel was part of it. Yet there were modern examples, too: the prosecution of Nazi Klaus Barbie in 1987, that of Vichy Militia chief Paul Touvier in 1994 and the conviction of Maurice Papon in 1997.

French courtroom art has a multi-faceted past. Here, long before the Terror trials of the French Revolution, big judicial moments were part of popular graphics. They can be dated back to the Middle Ages but their depictions blossomed in the 1770s – thanks to trials such as that of Antoine François Derues. Convicted of a double murder, Derues was burned alive on the spot where Paris' City Hall now sits. In prints that look to modern eyes like crude bandes dessinées, artists of the time portrayed his crimes, pursuit and fate. As print technology changed and improved, such visuals proliferated.

By 1825, La Gazette des Tribunaux ("The Court Gazette") was feeding the French court reports every day. Although the Gazette carried no images, others soon took up the slack – paving the way for a crime-obsessed petite presse. By the late 19th century, law courts were seen as an echo of the stage, with a complementary range of principals and supporting players. (Open seven days a week, on Saturday and Sunday the Paris courts were more crowded than theatres.) During the Belle Epoque, humor publications went mainstream and mockery started to play a central role in judicial coverage. The era's caricaturists drew a bead on egos and vanities – sometimes those of criminals but, equally often, of lawyers and judges.

The greatest such satirist was Honoré Daumier (1808-1879), whose first job was working for a bailiff. "No other artist," writes historian Colta Ives, "has ever been quite so fascinated by the legal profession or has proclaimed its endemic weaknesses so vividly." Daumier's cartoon series Les Gens de Justice ("People of the Court") ran almost every week between 1845 and 1848 and it remains as singular as Goya's Caprichos. Today, its original prints are highly prized and collected by many in the legal profession. At exhibitions such as 1999's La Justice ("Justice") or 2010's Traits de Justice ("The Art of the Courts"), Daumier is court art's benchmark.

But he wasn't the only one to see the courtroom as a social mirror. As visual coverage evolved, even the venue's topography became significant. Cartoonists such as Jean-Louis Forain and Charles Léandre paid attention to its details – from the isolation of the witness box to the elevated perch of the judge. (Both lampooned the way judges literally look down on defendants.) If the meat of such judicial art was spectacle, courts were also shown as what historian Frédéric Chauvaud calls "a theatre of social oppositions and of confrontations between the public and private spheres."

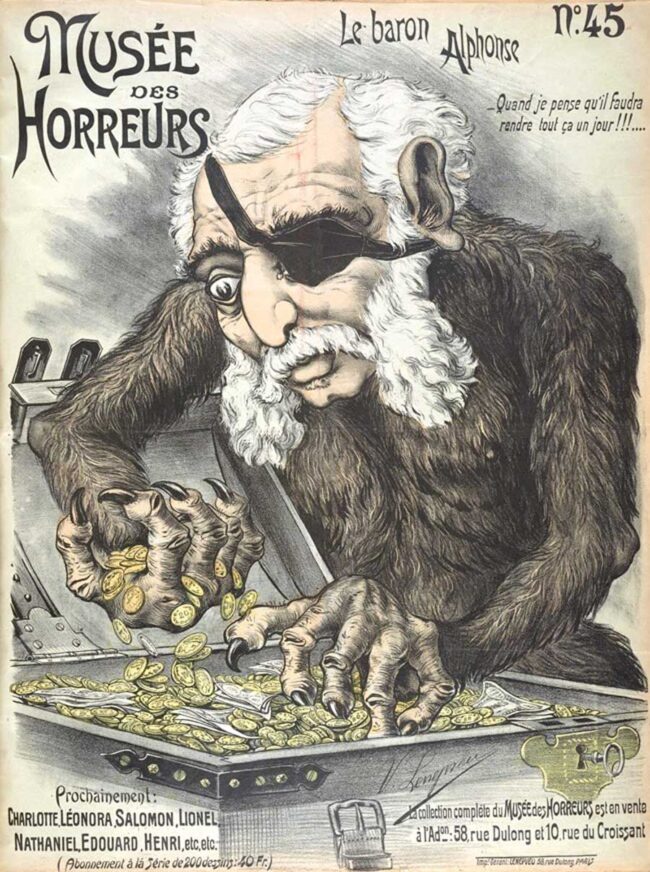

Not all judicial satirists, however, were laudable. Between 1889 and World War I, some of the most popular were also anti-Semites. The most aggressive of them were Adolphe Willette, Caran d'Ache (Emmanuel Poiré) and Jean-Louis Forain.[1] All three founded anti-Jewish satirical journals, with Forain and Poiré uniting on the repugnant Pssst! (1888-1889). Like cartoonists such as Charles Léandre, they helped visualize and spread what critic Marie-Anne Matard-Bonucci calls "antisemyths".[2]

At the time of the Dreyfus trials, newsstands were papered with journals, each one of which blared forth its cover image. Covers were also widely reproduced as posters. Thus, simply by virtue of being published and sold, cartoons depicting Jews as uniquely mendacious and traitorous were widely seen.

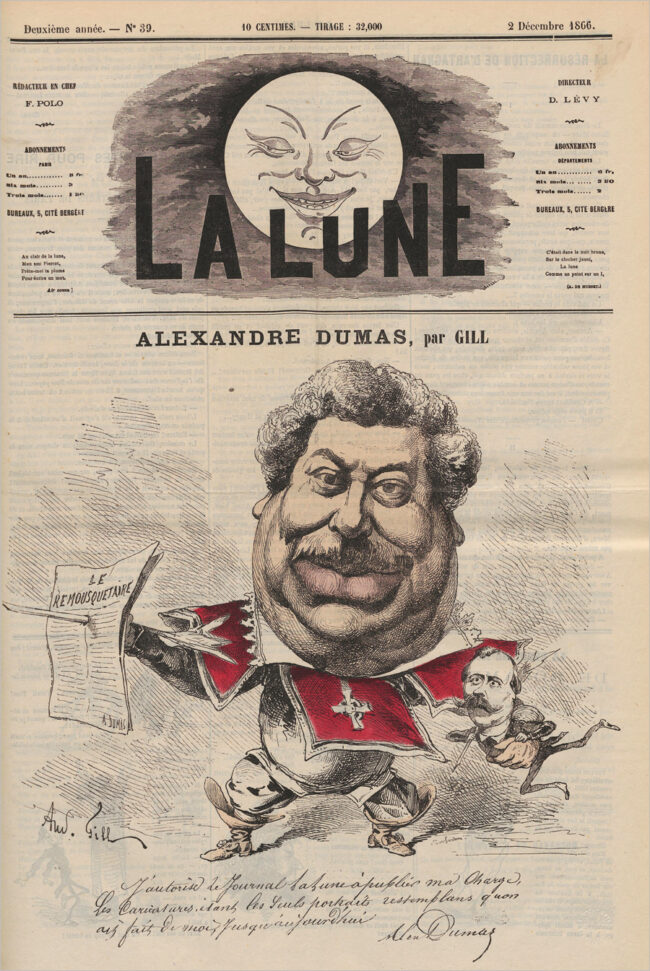

French cartoonists have never been gentle. But much anti-Semitic satire from the Dreyfus era has a fixation and hysteria all its own. Their uses of "Jewish characteristics" differ from, for example, racist caricatures of Alexandre Dumas. During the 1850s and 1860s, the author of The Three Musketeers is always drawn with "black features": i.e. wild, frizzled hair, large lips and bulging eyes. But, Dumas' grandmother having been a slave in what is now Haiti, the tropes were clear jibes at his heritage. But they had another, very specific, subtext. That was Dumas' exploitation of ghostwriters, the lowly profession then known as "négres". Here was a rich celebrity, they implied, descended from a slave – yet he was perfectly happy to go on enslaving others.[3]

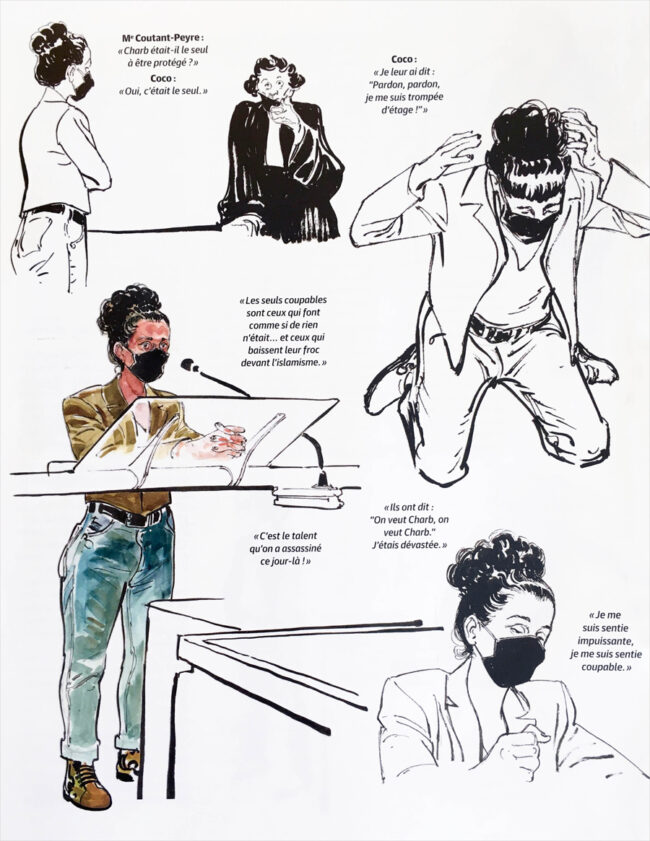

François Boucq is well aware of all this history. A close friend of the murdered Cabu, he began his own career as a press cartoonist. At the start of the Charlie Hebdo trial, he says, "I decided I needed to be as respectful as I could. Not just because there's such a long tradition of French courtroom art but also because so much of it took the path of caricature. I thought that, especially when it came to this trial, I should be respectful of whatever I saw … including the accused. For me, that really mattered."

In fact, Boucq's central problem turned out to be more modern: how could he draw with everyone in a mask? (Masks are legally required everywhere in France.) "I complained a lot about that but I came to terms with it. In terms of drawing, there are really two aspects. There's the totality of a body and its disposition. Then, there's the gaze. The gaze, the regard, is critical and, in a sense, everything else is peripheral. But what underlines someone's interiority is the way he holds his hands, how he approaches the bar, how he moves his feet. All those explicit things … I paid close attention to them."

After his first day, Boucq told Le Point, "You have to interpret the moment, capture in a single drawing many things that are happening simultaneously. You have to synthesize, including the way you interpret characters… All day I was thinking of Daumier. Because, even when he showed some lawyer asleep, everything he produced was so alive."

In the end, the masks proved oddly helpful. With defendant Ali Riza Polat, for instance (Polat, 35, faced the heaviest charges)."As long as he had the mask," Boucq told radio's Guillaume Erner, "Polat had a very intense, rather handsome gaze… something almost flamboyant. But the moment he took it off he became indifferent-looking, almost a bit of a hick or a Neanderthal. The mask revealed all that intensity he carried inside."

Boucq found the masks helped him grasp "what went on internally". But masks offered no protection from the trial's images – especially those shown during the second week. In calling Commandant Christian Deau to the bar, court Président Regis de Jorna gave all attendees who wished to leave permission to do so. First using only words, Deau described all the events of January 7, 8 and 9. He took his listeners from the first fusillade through the two Kouachis' flight, superimposing Amédy Coulibaly's Montrouge killing, the Hyper Cacher hostage crisis, the Kouachis' final shootout and the supermarket storming. He spoke for four hours.

Then, after a ten-minute pause, a giant screen was lowered. The bailiff unsealed a set of CD-ROMs and Deau began projecting the visual evidence. "Step-by-step," wrote Henri Seckel in Le Monde, "his voice brought us closer and closer to horror." Clicking his mouse on individual cavaliers (those yellow numbers propped beside corpses or cartridges), Deau guided viewers through the rooms at Charlie. He kept his voice, writes Haenel, flat and methodical.

This time, the version was one of statistics. Thirty-four empty cartridge casings at the scene. The first body shown, that of Charlie's sub-editor Mustapha Ourrad…four bullets. "Advancing, we see a second corpse, that of Franck Brinsolaro… four, perhaps five, bullets. Monsieur Brinsolaro was the bodyguard of Monsieur Charbonnier… This brings us to the main room; here, the first corpse is that of Monsieur Verlhac… two bullets." Bernard Verlhac, Tignous, who was still holding his pen. Cavalier F, economist Bernard Maris; Cavalier D, columnist Elsa Cayat. Cavalier H, the body of Cabu; Cavalier C, that of Georges Wolinski. E, Philippe Honoré.

For each one, Deau enumerates the bullet count. "Cavalier B indicates the body of Monsieur Charbonnier.… seven shots from a Kalashnikov, three at head level; all fired from less than ten centimeters away. As we zoom in, we see that blood has reached the ceiling."

"We obeyed," wrote Seckel. "We zoomed… and we saw." So did Boucq and Haenel. Although Haenel includes just a few of Deau's words, he says he scribbled all of them down compulsively. Boucq, however, set aside his pencils. "I made just a single drawing, for myself."

There was also a Cavalier A: the body of invited guest Michel Renaud. Renaud had come to Paris by train from Clermont-Ferrand, lugging along a ham as a present for his friends. He is usually forgotten in accounts of the day, as are the building's maintenance chief Frédéric Boisseau and the police officer Ahmed Merabet. Boisseau, however, was the first person killed. Merabet, who rushed to the scene, was shot in the street and then executed. Filmed from a rooftop, his death became a snuff film – exploited by media all over the world.

The reality behind Deau's statistics was stark. At Charlie, 12 corpses and 11 wounded, four of those critically. In Montrouge, Coulibaly killed a policewoman, Clarissa-Jean Philippe; he sent a bullet through her partner's face. By dawn on January 9, the two Kouachis were barricaded in a suburban print works. They were holding the owner hostage. Unbeknownst to them, however, one of his employees was hiding under the sink – where he remained, terrified, for more than eight hours. That same day, in the Hyper Cacher, Coulibaly murdered four people and held seventeen others for four hours. Some of them spent that time face-to-face with him and the dead. Others were hiding in the basement's walk-in freezer.

Haenel and Boucq already knew much of this. But, as the days passed, other statistics surprised them. Saïd Kouachi, they learned, had just "a tenth" of normal vision. Ali Riza Polat possessed six telephone numbers, Amédy Coulibaly thirty. Between the end of 2014 and 1:30 am on January 7, 475 calls were made between them.

Haenel and Boucq were also stunned when a lawyer pointed out that his attacks had cost Coulibaly €12,500. "The number froze us, not because of its amount, but because it was such a brutal proof that crime can be quantified, that killing is an expenditure just like any other and that the death of seventeen people cost money."

The observers discover that, with few common interests and fewer loyalties, what unites the defendants is not religion but money. In the end, their tale turns out to be one of "people under pressure, small time mechanics who find themselves at bay, implacable drug dealers, truly pitiful swindlers. A tale of little gangs and groups who tear one another apart even as they make their money poisoning everyone around them."

Yet that money is never, can never, be enough as fifty-year-old Metin Karasular reveals on the stand. Karasular, a Kurd, runs yet another "garage", also one that serves a front for trafficking.

Coulibaly shows up there with a car as 'security', a car Metin Karasular claims he sold to "a Greek". But, whatever sale took place possibly also involved drugs, arms or explosives. All Karasular's stories are wild, convoluted and incompatible. The more he hears, writes Haenel, the more he comes to realize that "hell has a special dimension all its own, one which slowly soaks up all the lesser depravities and feeds even on the tiniest of crimes."

Hundreds of telephone calls are logged and explicated. A list of Coulibaly's arsenal turns up in Karasular's garbage. (It seems to have been written by Riza Polat.) The saga mounts towards an operatic apogee: now Metin Karasular owes €2,000, money that Coulibaly shows up in person to claim. Since he enforces his payments with beatings, the Kurd reluctantly forks it over.

"But that damn black," Karasular suddenly cries, "All he did was throw it on the floor! He was vicious!" This, Haenel realizes, is the actual blasphemy. "He who can treat money like shit reigns over all who respect it."

Janvier 2015 could have been just a string of such narratives. For, between their petty quarrels and endless bouts of PlayStation, their juxtaposition of prayers with prostitutes, these are lives of a stunningly banality. Confronted with a hundred and fifty witnesses, however, Haenel and Boucq stick with their métier. Everyone gets their attention and appears as an individual. Boucq's illustrations are a tour-de-force of drawing from life.

Not infrequently, there are bombshells, many of which originate from women. For, rife as proceedings are with loving mothers and dutiful wives, violence against females permeates the evidence. Some who experience this are clearly cowed. But others point an accusing finger. "I can't say more because they'll rip me apart"; "They're going to bleed me to death"; "I wasn't there to open the door of the toilet so he beat me"; "He hit me just because I hadn't bought his daughter Nesquik ".

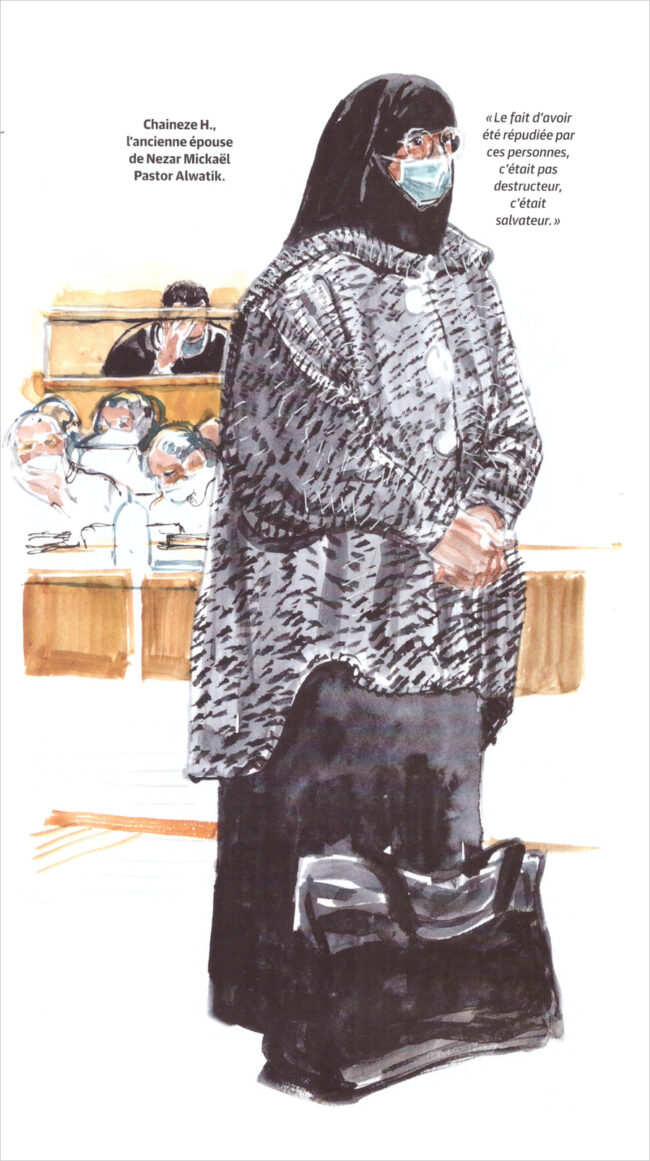

Key revelations come totally out of left field – as in the case of Nezar Mickaël Pastor Alwatik. Alwatik, who is a Moroccan Muslim, celebrates Shabbat every week with his Jewish sister. In order to please the mother he claims to adore, he says he solicited Coulibaly to find him a wife. Unhappily, Coulibaly's choice turned out to be a fundamentalist. Thus, concludes Pastor Alwatik, he is no jihadi. Quite the opposite: he's a man denied his video games and television by a "ninja" wife he doesn't like. ("She's the religious nut, her in that Quechua tent.")

Except that his wife, Chaïneze Hamouche, also appears. She indeed appears devout, veiled from head to foot. But once she begins to speak, the tables are quickly turned. Point by point, Hamouche paints the very portrait every defendant has denied. She describes – in detail – that "Islam" her husband, Coulibaly and their associates promote. It's a maverick, anti-Semitic "sect" that exhorts violence and entertains itself at home with bloody videos. "That I could ever have rubbed shoulders with such people," says Hamouche bluntly, "totally disgusts me. Especially since I am someone who displays my belief. These are people who dishonor Islam, drag it into the dirt."

Another woman who disconcerts the court is Sonia Mejri. Mejri, 31, speaks by video link not because of Covid but because she is in jail. After six years in Syria as an ISIS wife, she returned to Europe in 2020. Mejri recounts those years in the desert, her marriage arranged through Facebook, a daily life limited to childcare and household drudgery. She had two husbands but never really knew their names. She says the first one – who was killed – told her "he organized Charlie and the Hyper Cacher". The life she relates was interspersed by rapes "including those of the kind forbidden by Islam."

Her testimony finished, Mejri asks for a few more seconds. Given the time, she leans forward. "I want to say something to Charlie Hebdo … It's important for you to continue. What they want is to create social disorder. You represent that liberty they hate the most. So don't stop, don't give up."

The response to this admonition is mixed. Yet Haenel and Boucq have already had a similar jolt. One afternoon, while the court is taking a pause, they notice three defendants huddled together, laughing. They are poring over the latest copy of Charlie.

Both reporters are astonished. But, as Boucq later tells French radio, "Essentially, they discovered Charlie just by being there, by appearing in a trial for which Charlie was one of the reasons. Many of them arrived without knowing Charlie existed – or, in fact, knowing what it really was."

As Riss has pointed out, this is not really about cartoons.

Some of the book's finest drawings deal with the siege at the Hyper Cacher. There, Amédy Coulibaly filmed his own murders himself. But – unlike the surveillance film taken from Charlie – no video from the Hyper Cacher is ever screened. This time, the cavaliers pass by in stills, video captures from the store's sixteen cameras. Coulibaly bursts in at 1:06 pm; he fires immediately on employee Yohan Cohen. Thirty-six minutes later, he has all the cameras unplugged. But, by then, there are four bodies.

The Hyper Cacher murders are tied to those at Charlie – but the carnage Coulibaly sought was greater. While demanding freedom for the two Kouachis (then surrounded by police outside Paris), he paraded an arsenal of guns and explosives. With them, police confirm, he could have obliterated the building.

Haenel and Boucq exert care depicting the siege. Yohan Cohen, who was 20, lay groaning on the floor for almost an hour. But within fifteen minutes, Coulibaly found and killed three other people. Philippe Braham was 45 and had done his Shabbat shopping. But, having forgotten bread, he returned that Friday. Michel Saada, 63, arrived at the door after Coulibaly's entrance. Zarie Sibony, one of two cashiers, was there – already struggling to lower the security shutter. She tried to signal that something was amiss, but the dapper retiree slipped under her gate. He only needed, smiled Saada, "to grab a couple of things". Seconds later he was dead.

Like other customers, Yoav Hattab ran to the basement. But the 21-year-old had seen Coulibaly prop one gun against a sack of flour. He re-ascended, grabbed the weapon and tried to fire – but nothing happened. Coulibaly shot him.

Just like 28-year-old Zarie Sibony, several other workers were trapped. One was of them was Lassana Bathily, 24. Just like Coulibaly, Bathily was a Muslim immigrant from Mali. The pair's respective families lived 12 miles apart.

Bathily was downstairs unpacking frozen food when the terrified clients pelted into his basement. He proposed using the back elevator to flee, but the group were too afraid. So he disconnected the cold room and hid them inside. He then grabbed the keys and determined to take his chances. Bathily gained the lift, escaping Coulibaly's gaze. But, as he raced out of the store's back entrance, all the police surrounding it tackled him. Thrown into handcuffs, he was questioned for more than an hour-and-a-half. During that time, Coulibaly ordered Sibony to check the storeroom. If she didn't find and bring him every hostage, he snarled, he would shoot her fellow cashier. Then, he would kill her.

Every time she descended, Sibony spoke with the hidden clients. Each time she re-emerged, terrified, and swore no one was present.

Sibony obeyed Coulibaly's every order. She put him in in touch with the police, helped him get a computer going, mopped up when a terrified toddler vomited. After each "assignment", she returned to her cashier's till – reflexively crouching underneath to pray that her death would be quick. But Coulibaly harassed her. 'You Jews love life too much," he said at one point. "You think that it's life that matters. But all that matters is death.'

Haenel found what he was hearing almost mythological. Sibony, he writes, seemed like a modern Persephone. "She was moving back and forth between the upstairs and the down, actively uniting the world of the living with that of the dead". Meanwhile, outside, Bathily had given his keys to police, explained how to open the steel security shutters and created a map of the store's interior. By 5:00 pm, a massive counter-terror force was assembled; ten minutes later, they stormed the premises. Although six people were wounded, no-one else died.

Lassana Bathily was there for the trial's opening day. He had waited five years, he told reporters, so he could speak about his friend Yohan Cohen. Twenty days later, he took the stand and did.

The pair worked side-by-side for two years, he said, "Cohen in his kippah and me with my prayer rug. Yohan was more than my friend, he was my brother". But, added Bathily, in the street Cohen tucked his kippah under a baseball cap. He also turned sacks from the Hyper Cacher inside-out. "He was afraid someone might see the logo and cause him trouble. I tried to tell him, 'This country is laïque; here, we respect each other'."

Président de Jorna questioned Bathily himself. What was it really like to be a Muslim and work for a kosher store? "There are ten Hyper Cachers in the Paris region," Bathily told him, "and seven or eight of those are being run by Muslims. For us as Muslims, Jews are our brothers.… At work, I fasted for Ramadan, I always had my prayer mat. All of it was fine with my colleagues. We never needed to talk about religion."

At the time of the siege, Bathily was waiting for his residence paper. But for his role in ending the standoff, President François Hollande made him a citizen. However, he told the court, "I was French before I received French nationality. The Republic, it's given me everything… So for me it's important to be here, it's important I serve as a witness for the victims at Charlie, at Montrouge, at the Hyper Cacher... Before any of us is an atheist, a Jew, a Muslim or a Christian, all of us are humans. Humanity comes first. "

In Janvier 2015, relief from overwhelming malevolence is – against all odds – found at the Hyper Cacher. "What Zarie Sibony and Lassana Bathily gave us, what I tried to convey," says Yannick Haenel, "is that there is something in us which always persists intact. Something that exists beyond the reach or power of the most destructive forces. There's something in us stronger than infamy, than barbarity… something irreducible. It's a capacity that evades domination and, for me, that's the 'truth' we finally heard."

For Boucq, the trial was a drama like he had never encountered. "We saw the worst kinds of cruelty and the very blackest tragedy. But, at the same time, we saw the most sublime responses. There were so many people who had aided others, who had risked their lives, performed heroically … it was the entire gamut human beings are capable of. In the end, that offered us something quite magnificent. Here we are in this sealed room, where there isn't even daylight. Yet we're presented with the synthesis of humanity."

That's exactly what the pair's book contains: those countless tiny specifics that, assembled, make up our lives. Whether it's the outsize glasses on Chaïneze Hamouche, the crumbs from a snack which covered Cabu's dead body or the poem a plaintiff's lawyer suddenly declaims;[4] all these details are life's connective tissue. Janvier 2015 doesn't offer a binary world, one that opposes the faithless and the believer, the unlucky and the privileged, the mocker and his target. It records the far less knowable world we all inhabit, one redeemed by our stubborn commonalities.

That's our world – every bit as horrific as it is glorious. Our world, the place where a Tout est pardonné is possible.

- Janvier 2015 by Yannick Haenel and François Boucq (Les Echappés) is available now from bookstores, newsagents and the publisher; subscribers to Charlie Hebdo can read the trial reports (also translated in English) on Charlie's web site; New York Cannibals by Boucq and Jerôme Charyn is out now from Le Lombard

[1] Such cartoonists were not isolated cranks but well-known figures of Belle Epoque bohemia. Active in its creative events, their art was published almost daily. Jean-Louis Forain was close with Edgar Dégas, Rodin, Renoir and Cézanne – all of whom were also anti-Semitic. While Le Charivari rejected him, his work did well in publications from Le Figaro to Le Journal amusant. It helped put caricature at the centre of Belle Epoque politics.

[2] Many caricaturists, such as Theodore Steinlen and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, made sinister use of such tropes in ways that stood apart from their usual cartooning. Lautrec became, as curator Norman Kleebatt writes in The Dreyfus Affair: Art, Truth and Justice, "almost the dominant illustrator of softcore anti-Semitic literature".

[3] Alexandre Dumas was unfazed by scorn of his racial heritage. He is famous for his reply to the jibe "Au fait, cher Maître, vous devez bien vous y connaître en nègres ?" ("Of course, dear Master, you recognize yourself in the Negroes…"), which was: "Mais très certainement. Mon père était un mulâtre, mon grand-père était un nègre et mon arrière-grand-père était un singe. Vous voyez, Monsieur : ma famille commence où la vôtre finit." ("Why certainly. My father was a mulatto, my grandfather a Negro and my great-grandfather a monkey. You see, Monsieur, my family started out where yours has ended.")

[4] Maître Jean Reinhart, representing Frédéric Boisseau's partner Catherine Gervasoni, finished his closing arguments with Rimbaud's famous Le Dormeur du val ("The Sleeper of the Valley")