Today on the site, we have two reviews for you. First, Tegan O'Neil returns with an assessment of Box Brown's latest comics biography, Is This Guy For Real?

Andy Kaufman was around for just long enough to ensure that people are going to be writing about him for a long time to come. There’s something sticky about his story in the mind, despite (or because of?) its brevity. Box Brown’s new biography of Kaufman, Is This Guy For Real? – The Unbelievable Andy Kaufman is careful to trace the means by which Kaufman’s lifelong obsession with wrestling informed his approach to comedy and performance. Wrestlers adopt larger-than-life personas, complete with accents and backstories – just like Kaufman, who sometimes pretended to be a lounge singer named Tony Clifton, sometimes pretended to be Elvis Presley, and sometimes a raging misogynist. Kaufman plays every role completely straight in the moment, leading to a tendency to be confused with his characters. He played the part of a meathead chauvinist challenging women to live wrestling matches a bit too well. Clips from his wrestling appearances reveal a focused performer who learned to relish negative attention from his audience.

The approach seen here is similar to Brown’s previous comics biography, Andre the Giant: Life and Legend. That book was effective because it focused on the tendency of its titular figure to accrue anecdote and story. Is This Guy For Real? charts more ambitious territory. It attempts to tell the story not merely of Andy Kaufman’s life and career from an early age through to his death, but the story of the Memphis professional wrestling scene in general and Jerry Lawler in particular. Whether or not you think this is an effective book will probably depend on the degree to which you think dozens of pages have to be spent on Lawler’s early career but a few panels spread across the book for Kaufman’s career on Taxi.

And we also have Edwin Turner, proprietor of Biblioklept, who makes his TCJ debut with a review of Paul Kirchner's Awaiting the Collapse.

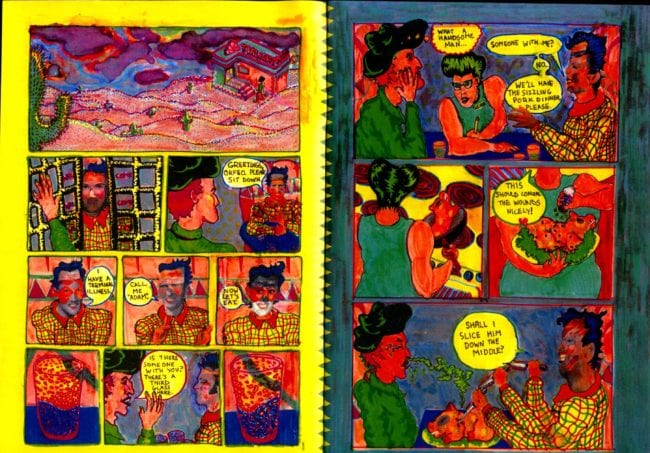

In "Highwire", the opening entry in Paul Kirchner's new collection Awaiting the Collapse, a tightrope walker navigates the skyway of a busy metropolis. The walker's magical high wire takes him over skyscrapers and into offices, dinner parties, supermarkets, and the homes of the gray citizens who, for panel after panel, fail to look up and see the miracle above them. In the comic's final panels, however, a man gazes up at the high-wire walker in a moment of recognition.

The gazer below, stocky, bald, and garbed in a trench coat and tie, bears more than a passing resemblance to the hero of Kirchner's cult classic The Bus. He strips away his business attire to reveal circus garb beneath and launches after the tightrope walker on his own marvelous trapeze. Thus Kirchner ushers us into the ultravivid, kaleidoscopic world of Awaiting the Collapse. Here, the miraculous is always potential, even in our mundane, mechanized workaday world---we simply have to look up to see it.

This insight---that a more colorful, more surreal world is available to us via imaginative perspective---is threaded throughout Kirchner's cult classic strip The Bus, which originally ran in Heavy Metal between 1979 and 1985. The Bus, which centered on a mundane hero's fanciful duel with the banality of everyday existence, found a second life on the internet through pirated copies---grainy, incomplete versions that hipped a new audience to Kirchner's fabulous comics.

Meanwhile, elsewhere:

—Interviews & Profiles. The latest guest on RiYL is Joseph Remnant.

And this isn't comics-related, but Jeannie Vanasco at the Los Angeles Review of Books has a conversation with one of the great writers on comics of our era, Daniel Raeburn.

The story of an essay or a memoir is really the story of thinking, of your own consciousness. Which requires you, as narrator, to be self-conscious, but not too self-conscious. Not completely self-absorbed. You’re walking a tricky balance beam. There are other paradoxes too, like narrative tone. You have to be confident in your telling of what happened, but not too confident about what it means. You have to have confidence in your own doubts, if that makes sense. They’re what propel personal narratives.

That’s why it’s probably best to err on the side of those doubts. A good rule of thumb comes from Kafka, who said, “In the struggle between you and the world, you must side with the world.” Another good line came from my friend Mark Slouka. After he read an earlier draft of Vessels, he called me and said, “Less knowing, more wondering.” As soon as he said it I knew he was right. I’d been trying to sound wise.

—Reviews & Commentary. Sam Ombiri writes about Nick Drnaso's Beverly.

Nick Drnaso gives a very specific amount of detail, and the stories move along rather rapidly – my eyes automatically go from panel to panel, as the story is so clearly laid out. It might even be my hundredth time reading the story, but it keeps me engaged every time. I can jump into any section, and it’s just as easy for me to recapture the essence of each moment as when I read it the first time. It’s clear that Beverly was made to be enjoyable to read, and the success of the comic is, for lack of a better term, almost severe. It’s strengths are obvious when you read it, so I don’t need to go on praising it. You don’t have to believe the stories in the book, because the book believes them for you.

And Jonathan Rosenbaum remembers the man who may have been the most valuable comics critic of the last century, Donald Phelps.

In some ways, the saddest deaths are those we only hear about accidentally. For me, Donald Phelps was one of the very greatest of American critics — not just literary critic and film critic, but comics critic as well — even though only two collections devoted solely to his written work exist (see above). I would love to imagine that many more will follow, because it’s clear that anyone who tracks down obscure journals, including his own (For Now), looking for Phelps’ insightful and highly original prose, will discover an unending bounty. But it seems like he never had much money, and even before the advent of Trump, Phelps appears to have lived his entire life in the shadows.