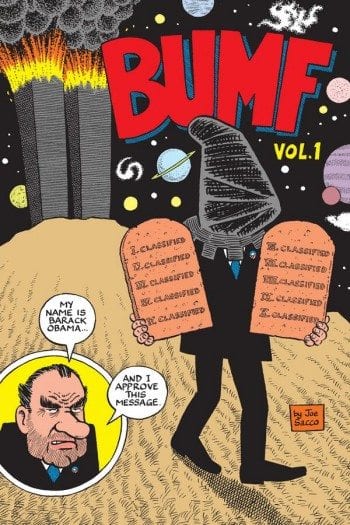

Bumf Vol. 1

Bumf Vol. 1

Joe Sacco

Fantagraphics Books

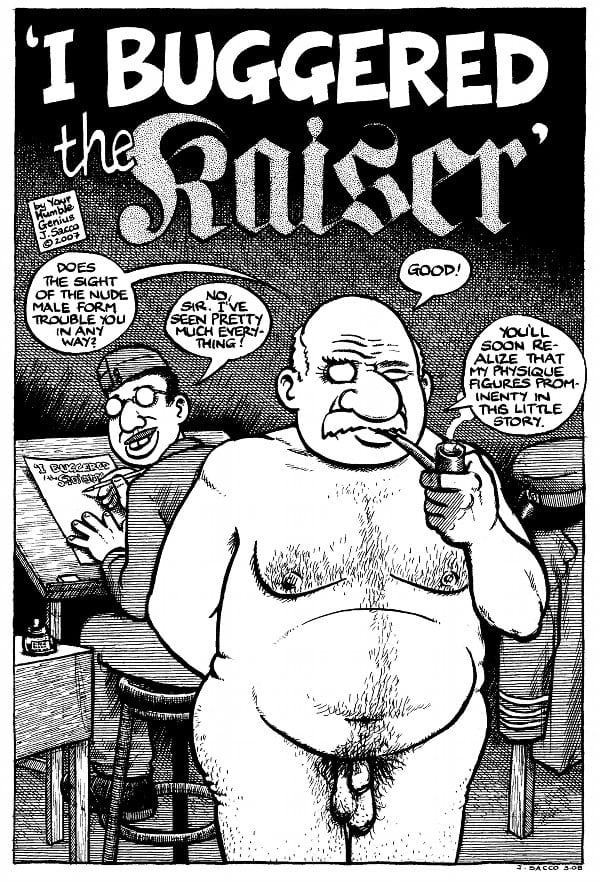

I have no idea to what extent if any Joe Sacco is aware of it, but his return to satire in Bumf is the comic strip equivalent of the methods of the Firesign Theater: A series of surreal vignettes that however much they seem stray from the central theme always revolve back to it. Its imagery is what you might have imagined listening to a Firesign album through headphones in a darkened room. In the process it returns surrealism to its original political aims. It's an odyssey through an inner space where you can open a door and find yourself at the Battle of Verdun.

The spirit of Bumf is not the arrogant disdain typical of satire but a crushing anguish. It's anguish in the first place that his country won't give him the one thing he most wants from it, which is to allow him to be one of the just. This anguish is built on a foundation much deeper than disillusionment with Barack Obama. It's the death of a hope, going back to the days of George McGovern, that the antiwar left might achieve its aims through the Democratic Party.

The central frustration expressed in Bumf's vignettes is in the helplessness of what you might call the genuine left to transfer its revulsion at targeted killing and government metadata collection to the general public. It means to break through public complacency on these issues by creating analogies with images that succeeded in inspiring opposition in other contexts: the Vietnam War photographs of the summary execution of an insurgent and a naked peasant child fleeing a napalm attack; the Iraq War photographs of torture at Abu Ghraib. As is commonplace, it identifies the policy of targeted killing with the weapon used to carry it out. The weaponized drone encapsulates Sacco's dilemma: The characteristics that make it the essence of moral hazard in Sacco's mind are the characteristics that make it popular with the general public.

As an opponent of NSA data collection Sacco is faced with the challenge of convincing a public that surrenders all manner of intimate personal information to private companies in return for free services to be driven to revolt because the government gets into the act. Sacco attempts to overcome this obstacle by manufacturing a tale of an innocent persecuted because her way of life fails to yield enough metadata to convince the government she's innocent. I'm mystified as to why he didn't avail himself of the genuine disclosures he could have used. Sitting on a silver platter was the tale of the NSA gnomes who used their work accounts to investigate people they were interested in romantically. It lends itself to dramatization and has precisely the element of the absurd he's pursuing throughout Bumf. If this was not a sufficiently direct action of the government, then there was the conflict with software companies over back door access to encrypted software, which a genuine instance of the government forcing people to do something they would have preferred not to. These alternatives might not have tempted Sacco to bathos the way the choice he made did.

The government's defense of data collection is that it uses innocent information to identify guilty information. Sacco's implication is that everyone has guilty information. Its opponents see it as circumstantial evidence that the government's true purpose is to spy on its citizenry as a whole. The implied argument is that (a) wide swaths of the population engage in activity the government could persecute them for; (b) the only thing that has protected the public from this threat was its ability to keep these activities private; and (c) now that the government has access to this information, it has only to swing the trap shut and all freedom will be extinguished, which was its goal all along. This possibility is represented by the final image of a King Kong-sized wolf set to pounce, an image that's quite striking regardless of how convincing it is.

The most extended analogy equates Barack Obama with Richard Nixon. Trite as this notion is, it serves Sacco quite well. First, it frees him of the reticence a liberal-minded individual might have about criticizing a Black president. Secondly, Richard Nixon was simply God's gift to satirists. His villainy is so inherently comic, his facial features so ripe for caricature that if you can't make a meal of it you're in the wrong line of business. The problem is that when you associate the policies of Barack Obama with the character of Richard Nixon you've said nothing about the character of Barack Obama. Obama's character may be wicked but it's not Nixon's. To invoke a devil figure is to invite mindlessness.

If Bumf doesn't garner the sort of broad attention and acclaim that Sacco's previous works have it won't be because of any lack of passion, imagination, or artistry, but because it's expressing something that's genuinely painful.

On Not Writing a Column About Ted Rall

Ted Rall is the Rolling Stones of the anti-Obama left. Just as the Stones were never for a moment taken in by Flower Power, Rall never for a moment imagined Obama was on his side. I've spent about six years not writing a follow-up to my earlier column ("Ted Rall's War", from back when the Journal could get ink on your fingers), focused on his Obama cartoons.

Whenever I write a column about political comics, the subject will usually reply that I am using my review to expound my own political beliefs. The reason they say this is because it's true. I am perfectly well aware of the response to commentary such as mine, which is, "When you draw your comic strip you can put your opinions in it." Besides, if you had to interpret the opinions of an opinion journalist the same way you interpret the creative work of an artist, that would be the problem.

Therefore I resolved in my notional column about Rall to restrict myself to the aesthetics of his Obama cartoons. However, as I composed the column in my mind I found my thoughts veering into political issues, like a drunk driver struggling to stay in his lane but inexorably heading into oncoming traffic. On sober reflection, I realized that between Rall and me I was the one whose outlook was being warped by his personal rooting interests. As the 2012 election drew near I also came to realize that the column I was not writing was being motivated less by Rall than my anxiety at the prospect of the country being turned over to what had become an all but explicitly White Supremacist party. (The maneuver Rall presumably had in mind was that he would defeat Obama and then turn around and defeat whoever replaced him, like George S. Patton's postwar wish that he could have rearmed the Germans and gone to war against the Russians.) Again, when reason returned I realized that if Obama were to lose it would be entirely due to things he had done and nothing to do with anything Ted Rall had done. Also, Rall has a blog and a sharp tongue and I'm afraid of him. My only advantage in such an exchange would be that Rall would have to explain to his readers who I am. In any case, my fears were entirely unfounded because in the states that held the balance of power Obama was leading wire to wire.

If I imagined a column that would refrain from attempting to rephrase Rall's opinions to make them look stupid and call it criticism, the only points I had to make were the ones I made in "Ted Rall's War". This was primarily that he had abandoned the idiom that had produced his best work, examining public issues from the point of view of ordinary people rather than the mighty, for an idiom that required skill at caricature, which is not his strong point. The trouble was, I knew the answer to that one too: If you're an ambulance driver and a house is on fire there's no point in looking for an ambulance to drive, you just fight the fire as best you can.

Over the last two administrations Rall has approached his cartoons as a duel between the cartoonist and the head of state. This is a classic strategy of the political cartoonist, guaranteed to draw the ire of people who identify with the head of state. Rall was confronted with the criticizing-a-Black-president problem late last year when the Daily Kos website dropped his cartoons, charging that his Obama caricature was racist. This is demonstrably untrue. Rall's caricature of Obama is measurably less derogatory than his caricature of George Bush. Rall portrayed Bush as an dimwitted, evil gargoyle. Obama he portrays as a moral imbecile. This would be a challenge to the most skilled caricaturist. Imbecile is the easy part. Identifying the imbecility as moral rather than intellectual is tricky. I swear at times Rall was an inch away from portraying Obama in a dunce cap with snot dribbling out of his nose. I can say from personal experience however that accusing Rall of racism is something you do when you want to shut him up. It's a weakness and you ought to lie down and get over it.

The column I never wrote was going to be called "Ted Rall Would Have Hated Abraham Lincoln". The premise imagined a 19th-century Ted Rall as a firebrand cartoonist for The Liberator, which I think is giving exactly the right amount of credit. The point I intended to make was that if this Ted Rall existed then we would have cartoons of Abraham Lincoln beating slaves. I understood that this would involve a false equivalence between Obama and Lincoln. For one thing, Lincoln came to the presidency mentally prepared for a civil war. I like to imagine Hillary Clinton standing at the inauguration with that tight little smile on her face, knowing what was coming and knowing there was no point in telling him because he'd never believe it. Barack Obama has become one of those mordant fables of American history, a Black man raised among White people who concludes from this experience that all conflicts are resolvable. This lifts him to the highest office in the land, where he discovers that to much of the population the only purpose a Black president can serve is to tell Black people to know their place and expect nothing from their country.

I reveal this tendentious and frankly embarrassing concept only because it made me realize something important. I realized that when you are tempted to dismiss someone's political goals as impractical, as I might do with Ted Rall, you have to take into consideration the history of the Abolitionist and Civil Rights movements. Every step along the way to emancipation and racial egalitarianism was impossible. It was impossible that the nation would engage in the apocalyptic war required to free the slaves. It was impossible that the Democratic Party would demolish its bulletproof electoral coalition by writing racial equality into law. What the Abolitionist and Civil Rights movements teach is not that everything is possible. What they teach is that the impossible happens when the alternative is also impossible. It was impossible that the non-slave states were going to allow slavery to be extended into the western territories, impossible that the slave states would be allowed to secede, impossible to continue to forever pretend a brutal segregation was the natural order of things, and suitable for a country that makes freedom its brand name. The proposed impossibility that Ted Rall depends on is that it's impossible for a society to maintain a social order that has injustice built into it. I won't beg the question, except to say that the hidden strength of capitalism is that it doesn't require people to be any better than they are.

Anyway, getting back to the point, what I didn't realize while I was preparing to make a fool of myself was that there was no need to invent a 19th-century Ted Rall who disapproves of Abraham Lincoln, because the one we have now doesn't approve of Lincoln either. This underlines the ultimate reason I had no business writing about Ted Rall: There is such a cognitive dissonance between the way he views the world and the way I view the world that half the time I don't understand what he's saying. For instance, for the longest time the belligerence of his rhetorical style blinded me to how many of his positions are essentially antiwar. For instance, his support for Muammar Gaddafi seemed perverse to me until I realized that it's not that Rall won't make Machiavellian compromises with reality, but that he will do so only for the sake of peace. That is, unless I'm over-thinking things again, and he supported Gaddafi simply because Gaddafi was nominally a socialist.

There is an undercurrent of practicality even in Rall's most ambitious goals that I have a hard time comprehending. For instance, for the longest time I couldn't conceive that he actually thought socialism could be brought about through the ballot. Upon deeper thought I realized that bringing about socialism through elections is a lot more likely than through revolution. It's a somewhat larger snowball in a slightly cooler Hell, but it's measurable. And it addresses a problem. Liberal democracy developed incrementally over centuries of oppression. The initial assumption was that socialism would stand on the shoulders of liberal democracy and produce something more just, more rational and more fruitful. What the history of real existing socialism indicates is not so much that socialism won't work as that it put you back at square one, and you'd had to go through that shit all over again. In pursuing socialism through elections Rall is attempting to put socialism back on the shoulders of liberal democracy.

Another reason for my hesitation is that I wasn't that sure how many people other than me cared about Rall anymore. I hasten to add that I'm really no judge of what people in general care about. For instance, there has been nobody more passionately opposed to targeted killing than Rall, and I've paid fairly close attention to that issue, and I never got the feeling that Rall was on the center of the opposition. (Rall is so enraged at the strategy that he makes only the most schematic arguments against it. This would have been a valid subject for comics criticism, but coming from me it would have been concern trolling.)

The impression I get is that Tom Tomorrow's This Modern Life has a much higher profile among genuine left political cartoons. I must say, though, that when I read them side-by-side Rall is the one who had me defending my own positions in my mind. Tomorrow is not so much a cartoonist as someone who's found another way to get people to read editorials. You could drop the pictures and the balloons would get along fine just by themselves. The problem with an appeal to reason like Tomorrow's is that it's an invitation to agree to disagree, if only because you can only fit so much reason in those little boxes, however text-heavy. Rall's appeal to abstract justice seems better suited to the medium of the cartoon.

In the end I got so aggravated with Rall that I dropped him from my GoComics page. If you want to score it that way, I suppose that means that Rall wins.