Bruce Canwell has the highly enviable job of reading and researching comics, and then writing about them for IDW Publishing’s The Library of American Comics imprint.

A comics reader from an early age, Canwell’s letters and those of future LOAC creative director Dean Mullaney appeared frequently in Marvel comics during the 1970s. When Mullaney published Don McGregor's and Paul Gulacy’s groundbreaking comic novel Sabre in 1978 for Eclipse, Canwell was one of the first to order it.

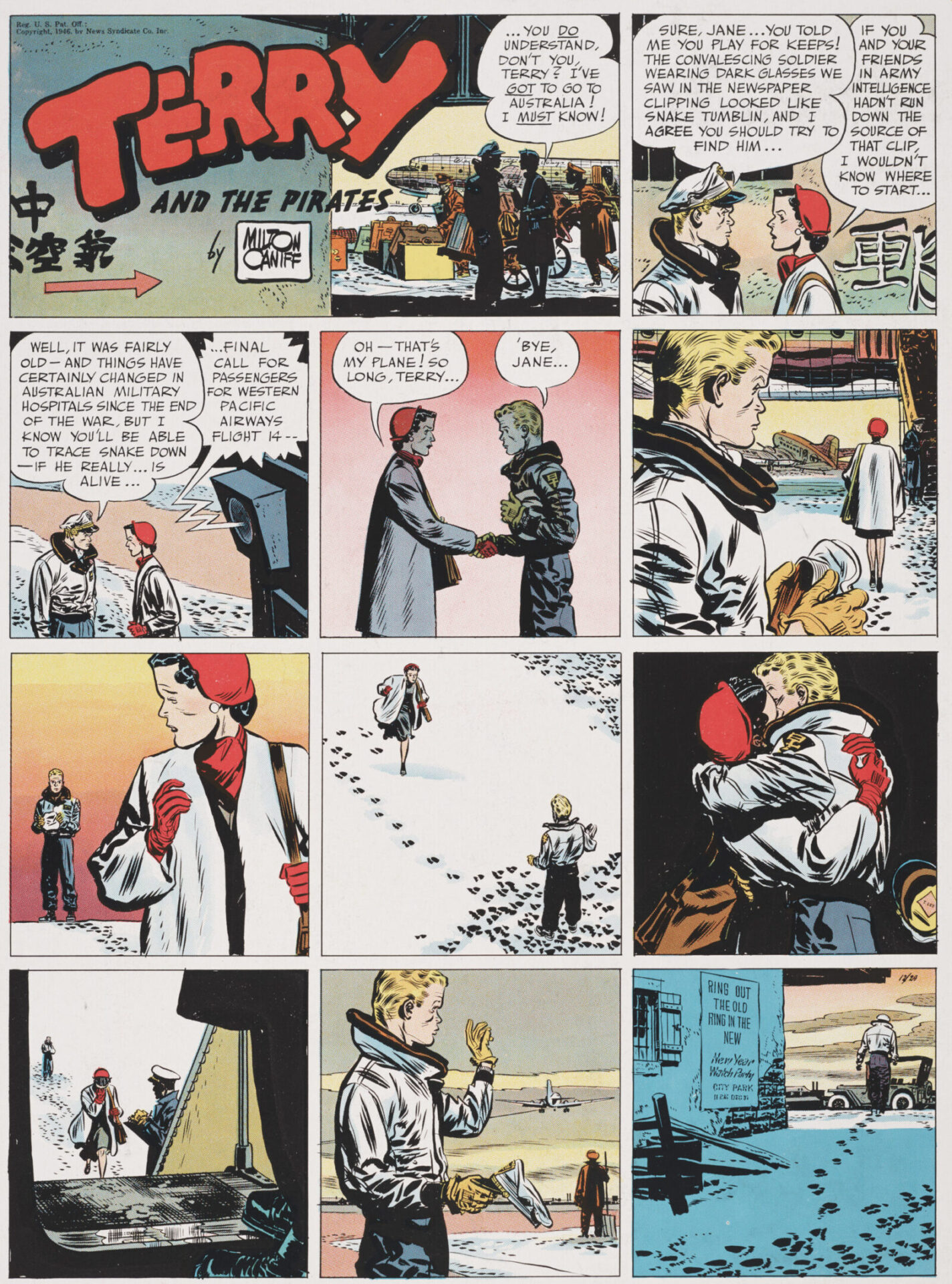

In the early 2000s, Mullaney approached IDW about publishing hardcover volumes of American comics. Canwell came on board as the associate editor. Together they decided to launch LOAC by reprinting the first two years of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates. Since the release of that tome in September of 2007, Canwell estimates LOAC has published a total somewhere in “the low 200s.”

Michael O’Connell, who’s written about Milton Caniff for The Comics Journal, talked to Canwell via Skype about his journey through comics, and what LOAC has in store for 2021.

* * *

Michael O’Connell: When did you get interested in comics and comic strips?

Bruce Canwell: My local paper in the town I grew up in had like an eight-strip comic section. So, a day wouldn't pass where you didn't read Peanuts and Beetle Bailey and The Phantom and Redeye. And I think they had Mark Trail and The Heart of Juliet Jones. It took me a little-- it took me many years before I was willing to [read] The Heart of Juliet Jones.

Which now is considered a very important strip I guess, or a much admired strip.

As we get older, hopefully, we look at material with a more knowing and considered eye, and I can see things in Juliet Jones today that I could not see [at] probably age 6 or 7.

When you've got only eight comics to a section, that’s like a shotgun approach. Here’s what we can do to appeal to the biggest or the widest audience.

It was a big deal if we went and visited relatives. None of our relatives lived close. So, on those times when we'd go visit relatives, you could find newspapers from their local towns and they had different strips than you did. That was something of an eye-opening experience, especially on the Sundays.... My initial exposure to Prince Valiant as a kid, I just found it impenetrable. It wasn't a comic. There were no word balloons and it was all captions under the artwork. It just seemed too static for me. But it was still an eye-opening thing. You always looked forward to the chance to see different newspapers and see what people had for different strips.

How did you become somebody who writes about comics, who's a comics historian?

The Reader's Digest version of it was from comic strips there were also comic books. In the '70s, Dean Mullaney -- the creative director of the Library of American Comics -- and I both appeared regularly in the Marvel comics letters pages. When Dean started Eclipse Comics, I was one of the first persons to order a copy of his inaugural effort, which was the Sabre graphic novel by Don McGregor and Paul Glacey. I got my copy, but we still had no person-to-person. It was a business transaction. I sent him money. He sent me the book. Fast forward to early 2006, Dean had been out of the business for a number of years and was thinking about perhaps getting back in, in some fashion.

He googled Eclipse Comics and it so happened I had written an article for an online publication, and I had mentioned Eclipse, and I had mentioned that Sabre arrived at a time when I was losing interest in comics and it helped revive my interest in comics. So Dean saw this article, he saw my name, he remembered me from [the] Marvel comics letters pages, and reached out to me. We exchanged a batch of emails and we discovered that we were really very simpatico in our tastes and in our approaches. We kind of said, we should do something together. What should we do?

And at that time, the strip reprint business was in its infancy. There had been a flurry in the 1980s between Kitchen Sink and NBM and a number of different publishers, Blackthorne Publishing-- they came and they went, or at least lost their interest in strip reprints. So things were pretty fallow until Fantagraphics revived it with [The Complete] Peanuts, and then they did Dennis The Menace, and IDW at the time started Dick Tracy.

That was at the time we were talking about things, and we both had a love for Milton Caniff and for Terry and the Pirates, and so we said, "We ought to do Terry and try to do it right. You know, do it big and integrate the Sundays and the dailies and do the Sundays in full color.” We agreed that that's what we would launch with, and that's when the Library of American Comics was born. Our planning started in 2006, so really 2021 is our unofficial 15th anniversary.

How many books have you put out since then?

We are in the low 200s. We’ve been busy boys.

In terms of concept and execution, what do you think the library's biggest successes have been?

Everybody always argues about what's the exact number. Nobody pinpoints it. Everyone has a different opinion, but everyone agrees. There are very few art forms that are native to America. But comics, the newspaper comic, is one of them. And nowadays with newspapers really no longer being part of the fabric of everyday life the way they used to be, we are 200-plus volumes strong in preserving this portion of Americana, this portion of this native American art form.

I think we've captured a decent depth and breadth of the material. And certainly, we're very collegial with the other people who plow this ground with us — Fantagraphics and Charlie Pelto over at Classic Comics Press, and Peter Maresca at Sunday Press Books. When you take a look at the totality of what we ourselves and our friendly competitors have done, we've really helped, I believe, preserve material that deserves preservation in a lasting format, so generations to come can at least explore this to the extent that they have an interest in doing so. Certainly, we hope that [there] will be renewed interest with each passing generation.

When you talk about the people who put out the earlier reprints in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, many of them had grown up with the strips or at least were familiar with them, maybe from their parents. The same could be said of their audience. But now, you have readers in their 20s who have no history with these strips. Are you able to grow an audience and grow an awareness with people who may not be familiar with these much older titles?

A qualified yes. The email and social media input that we get indicates that there is a certain slice of our readership that is in fact younger than 50-something or 60-something. I would tell you the numbers for younger readers are probably not what any of us would like them to be. But, I have this discussion with my comics-reading friends, who grew up as I did reading Marvel comics or DC comics or Gold Key comics, and seeing the superheroic sort of things, or the science fictional things that were prevalent at the time. Those things are not prevalent now, but I still believe there are a strong number of comics readers in the younger set, they're just coming at it with things like Dog Man or Diary of a Wimpy Kid. And as they grow older, things like Lumberjanes and other things that are available out there for the younger set. I like to think a number of those people as they grow older will stay interested in comics. Their tastes will mature, and they'll be looking around for other things in comics that will match their growing maturity as readers. I guess I have to believe that that over time there'll be at least a drip feed of new readers who come in and discover this material.

It helps that we have universities like, obviously, the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State, and Michigan State University has extensive collection. Syracuse has Hal Foster's papers and others. Boston College has Harold Gray's papers with Little Orphan Annie. It helps that the colleges have this material as well. Academia has found comics and has embraced them. So there are different tributaries that can feed into this river. And now we just kind of hope that for generations to come there's going to be a certain level of interest that will help this work live on and help our contribution to it live on, and maybe inspire another round of comic scholars to go beyond what we've been able to do as more and more information becomes available.

Terry and the Pirates is widely considered one of the best, if not the best adventure strips in the history of comics. It also represents a milestone in the history of visual storytelling. Do you have concerns when you point a younger audience toward that material, which they may only see outdated concepts and stereotypical representations that may turn them off and cause them to dismiss the work as a whole?

Yes. As a matter of fact, I've been talking about doing some writing along that line. I think one of the very, I won't say dangerous, but one of the unfortunate things that goes on today is the viewing of past material without any historical perspective, and viewing it through a modern day lens and expecting that's the only lens that's applicable. I think that does the material a disservice. To the extent that I'm aware that's out there, yes. I guess I would say that's a concern. But, you also hope that there are a number of people who will understand that the world was different. The world is an evolving place, and you can't get where you are today unless you take steps from a less evolved state.

So, you’re reading work from a less evolved state. Is it that Milton Caniff was an evil person for drawing Connie with big ears and buck teeth and using him for a number of humorous situations? No, he wasn't evil. That was an accepted paradigm [at] the time. And in fact, when you compare what Caniff does to a lot of his contemporaries who are also using Asian stereotypes at the time, his Asian characters are generally more well-rounded. Even someone like Connie, who is used for comedy effect, he's used for more than comedy effect. He has roles to play above getting cheap laughs. That helps transcend the time. And so, does Caniff deserve criticism? Sure. He drew it. But did he try to go beyond the easy route, the basic stereotype that he could've gotten away with, that so many of his contemporaries got away with? I think he deserves credit for saying, "I want to create multi-dimensional characters rather than just rely on simple stereotypes.”

By the time we get to World War II, Connie is an officer in the Chinese Army.... Caniff was not afraid to let his characters grow and change. He just didn't have interest in doing cardboard cutouts. He wanted some added dimensionality and he was smart enough to know, I think, that the more rounded your major characters are the more useful they are, and the more different ways you can pair them together to get interesting results. I like to think that some readers will be able to go beyond looking at things through a 21st century prism and saying, “Oh, it's stereotypical. So therefore it's no good.” There will definitely be people who do that.

How has the COVID pandemic impacted the Library of American Comics? Have you had to change your operations much?

We haven't changed. We definitely slowed. We've always worked virtually. I don't think we made a secret of this. I live in New England. Dean lives in Florida. Kurtis Findlay, who does a lot of our social media work and is helping to edit our For Better or For Worse series, is living in Vancouver. We've always been working in a virtual environment. Email and Dropbox are our friends. So that aspect of it, we haven't been affected but certainly, especially earlier in 2020 in the early days of the pandemic, and really throughout the summer-- entities like the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library were shut down. Most of the universities were shut down. That's the home of a lot of our source material, and suddenly that material was unavailable. You couldn't get the next round of Steve Canyon strips for a while because they were locked up at the Billy Ireland and nobody was there to scan them for us. It affected us in terms of our rate of production. It didn't really affect us in terms of the way we do production.

As far as distribution goes, did you have to slow down or did you have to delay or postpone books?

Not the way that the major publishers did when there was the springtime shutdown and comic stores were disrupted when Diamond shut down. A significant portion of our sales come through Amazon, and certainly Amazon was going gangbusters throughout the earlier part of 2020. We didn't have as many feeders as we normally do, but we still had major feeders that would get us to the audience. So it was more a matter of accessibility of material than it was a disruption in the supply chain.

Let's talk about your new volume of Steve Canyon. What can people expect?

This is volume number 11, which takes us into the 1967 and 1968. Steve goes undercover at one point to try to expose a neo-Nazi group. He meets up with an old friend from a prior story. That's a typical Caniff trope. Take characters and put them into different situations and bring them back in a new and different way.

Steve winds up in some trouble and Caniff trots out a familiar trope. I'll spoil the surprise. Steve winds up amnesiac. Amnesia was a staple of 1960s TV. Mary Ann gets a bump on the head, thinks she's Ginger, and then Gilligan has amnesia and [can't] remember who he is. All sorts of shows did all sorts of things with amnesia. It's probably not unusual that Caniff would trot this out at this stage. Looking back at it, I believe it is the first time that he'd used amnesia as a plot device since back in the war years with Terry and the Pirates and Taffy Tucker. He went a long way before he reused that sort of an idea.

Steve is getting into his usual international trouble. He has a few adventures with Doagie Hogan, who's always interesting and spices things up. The sharpness of their interplay has somewhat mellowed with time, but there's still some prickly moments there.

Stateside, Poteet is now a reporter at a newspaper that was based on one of the Dayton, Ohio newspapers that Caniff used to work at years ago, early in his career. Poteet manages to rub elbows with an Olympic hopeful because the 1968 Olympics were on the horizon. She and her new friend, aviatrix Bitsy Beekman, they both wind up having an interest in the same Olympic hopeful. So that creates some sparks. Poteet and Bitsy later do a storyline in Africa that allowed Caniff to tout a group of aviators -- again from Ohio -- that are sort of an airborne Peace Corps.

What are some of the other books that you guys are working on that you're really excited about?

In 2021, we'll have the last Chester Gould Dick Tracy. Volume 29 will complete his run [EDITOR'S NOTE: The book is now available].... To be able to go from that very early, almost crude Plainclothes Tracy material, all the way up through the glory days of the '40s and early '50s, through the Moon Maid period of the 1960s and the science fictional stuff.... He’s dealing with the same thing Caniff is in the 1970s, smaller strips, shorter stories. He's old man now, and he is out of touch with the youth culture. And yet he's still finding a way to tell interesting stories from within the framework that he is comfortable and knowledgeable about. And so, to have that entire warp and woof of a career available in [a] uniform edition, I just think it's an accomplishment we're justifiably proud of.

We're four volumes into For Better or For Worse, Lynn Johnston's really excellent family strip. Volume five will be out in 2021. [Also available now.]

We're going to have our 17th Little Orphan Annie volume. That will move Little Orphan Annie into 1955, which means that we will have more than 30 years of Harold Gray's Little Orphan Annie that we have put into print. And, again, that's-- I think that's an achievement to be proud of. Everybody knows Annie through the play and the movies, and the comic has sort of become secondary. The tail is wagging the dog, if you will. We've at least made it possible for people to go back to the original source material.

I think Little Orphan Annie is an amazing slice of Americana. It really does embody a certain amount of American can-do and the brash determination that we like to associate with the best days of the country. It's interesting to see that sort of spirit so consistently reflected throughout that strip.

Those are things that are sort of on the near term horizon. We have a couple of other projects that are still in the embryonic stage, so can't talk too much about them because by the time we firm them up, they'll probably look different than I would describe them today.

We definitely will have either toward the very end of 2021 or very, very early at 2022, we will have, believe it or not. Steve Canyon volume 12. We will take Steve Canyon into 1970.

The Comics Journal interviewed you and Dean back in 2013. At that time, you were talking about how you were planning to deal with creators’ rights. When it comes to older comics, where some materials may have fallen into the public domain, how does LOAC approach creators’ rights?

Our Alex Toth books are probably a primary example of the way we try to approach things. If in fact, there is a family or descendants and they have the ownership of a segment, as the Toth children do a certain segment of what Alex produced, we want to work with them. We will do a deal with them, like for the Toth children we did a deal. There was a certain royalty aspect to it as we sold units, that they made some additional money over time as those books sold.

Obviously, for things that are in the public domain and there are no real descendants or lineage, or if the strip itself is owned by King Features, and now a certain segment of the work has fallen into public domain, we still will collaborate with the owners, be it King Features or the Tribune Media Service or whomever, to make sure that we aren't stepping on toes.

One of our LOAC Essentials books was a year's worth of Krazy Kat. Fantagraphics had been doing Krazy Kat Sundays at the time, and had made talk about trying to do something with the dailies. And I think they did do a couple of daily books. I think they did a 1920 panoramic dailies [The Kat Who Walked in Beauty, 2007], I believe they were. We approached them and said, "We've got a year's worth of Krazy Kat. We'd like to do it in this format. Would you object to that?" We have a collegial relationship with the folks from Fantagraphics, so they said, "No, go ahead and play through. We have no plans for that material.” I think the overarching thing I'd say is that we try to understand where the material was coming from and try to make sure that we aren't going to be stepping on anyone's toes as we build our own plans, because fair is fair. The comics industry has a long and checkered history that everybody knows about of not necessarily always being fair to those who create or to those who own. So, we want to try to make sure that we give the appropriate due, you know, as we firm up different plans.

Since you and Dean last spoke to The Comics Journal in 2013, IDW has changed ownership. Has that change affected how you are handling creator’s rights?

The simple answer is no. People just sort of fall into the pattern they know. So over time, people have sort of come to the equation that the Library of American Comics is to IDW what, say, Vertigo used to be to DC, a smaller subset of the larger publisher. And that's not the case. Dean owns the Library of American Comics. There is a deal in place between IDW and LOAC. But if we have a project that we would like to do and IDW is not interested in it, we fully have the ability to do that project outside of IDW. It's just our relationship with IDW has been so good for so long that there's been no real need to do anything overt to change that picture. The relationship has worked so well if it ain't broke, don't fix it.

We continue to chug along as we have. I will honestly tell you, because I'm an LOAC guy, I'm not an employee of IDW. I've never taken a check from them. Dean winds up doing the most — 99.8% of the interface with IDW is done by Dean. And most of what I know about the changes at IDW, I've read the same articles you've read and the audience has read. What they're doing is in their larger plans and the larger amount of books that are put out, that's their business. It's not my business. So I have enough to do managing my business, let alone trying to get involved with either understanding or being involved in theirs. That may be terribly short-sighted of me, but that's the path I've taken.

Is there anything else that we didn't talk about that LOAC is working on that's worth mentioning?

We always have some dream projects that we'd like to do. It probably won't be in 2021, but we would like to do a compilation book of Sunday topper strips. Above Popeye or above Bringing Up Father, or-- above so many of the Sunday strips, the artist would do another smaller strip, entirely different characters, entirely different continuity. There's some really interesting stuff there. We just haven't figured out how to properly package it and what we would put in and what we would leave out, because those would be some, some tough choices.

I would love to do more Bringing Up Father. I would love to do more Li'l Abner, but one of the conclusions that we've seen in our sales figures is that comedy doesn't sell as well as adventure does. I keep hoping against hope there will be a sea change in the audience and that we can find a format that would help make it a better bet to do more comedy type stuff, because I would love to bring more [George] McManus back into print. Li'l Abner and Al Capp remain one of the fascinating strips and personalities in all of comics history. To be able to bring more of that to the fore and to be able to write more about it would be a great opportunity, but we never say never. There's always the possibility that we'll be putting something more along those lines on the schedule and in the years to come, because we may be slowed, but we're not done yet.