Blood banks and comics? The topic’s not as arbitrary as you might think. It’s quite a natural pairing, actually, both in Japan and in the United States, though for utterly different reasons.

In manga, one cannot call blood banks a major motif by any standard. But it is an important one that crops up at central moments in the medium’s history, serving as a touchstone in a number of artists’ self-fashioning, and a reference point in kashihon and kashihon-inspired comics’ much-celebrated link with poverty and the underclass. As I will explain in detail in the present article’s sequel, most artists who took up the topic did so within the framework of biography. These stories, whether hagiographic or self-deprecatory, typically present the selling of one’s blood to shady blood banks as an essential part of surviving the 50s before achieving stability or success in the 60s. There is also the unique case of Tsuge Tadao, who worked at a blood bank in Tokyo for ten years between the mid 50s and mid 60s, before creating a number of manga about the punks and down-and-outers who sold their blood there, and about the grisly practices and petty labor disputes that went on behind the scenes in the industry. Despite their variety of perspectives, these artists would probably have agreed with the basic point that baiketsu (“sold blood”) expressed how postwar growth, despite its promises of plenty for all, was marked by widening differences of class.

There is a touch of that in Mizuki as well. But what stands out strongly is his more American approach – “more American” not because he heavily appropriated from American horror and science fiction comics, but in the sense that it resembles what one typically finds in American horror comics, which was the use of current events and issues as a way to update established genre tropes. In Mizuki’s case, these would include: the subversion of scientific rationalism by the supernatural, the interpretation of human fallibility in demonic terms, and the foregrounding of the body as a object of scandal, disgust, and fear. Mizuki’s kamishibai background certainly helped in all of this. But while medical freaks and mad doctors abound in kamishibai, science and medicine do not seem to have been treated in that medium with the detail and specificity they were in American comics or in Mizuki’s manga – though I suspect someone might prove me wrong here.

Anyway, if only to help tease out the particularities of manga, let’s briefly consider American comics, where blood banks, bloodsuckers, and miraculous or horrendous transfusions are not uncommon. As the long roster of examples on the Polite Dissent blogspot shows, such motifs appear regularly in horror comics of the early-mid 1950s and superhero comics of the 60s and early 70s, with some examples dating back to crime, superhero, and fantasy comics of the 30s. The transfusion trope seems to have been the most common and, judging from the illustrated examples at Polite Dissent, has changed very little in seven decades, oscillating between super-powering and super-monsterizing, depending on whether it's a superhero or a horror comic. Most of the stories feature indirect transfusion from one person’s arm to another through tubes and bags. As general transfusion practice, I believe this was rare after the development of reliable blood storage and transportation facilities after World War II. But then again, in most of these stories, getting blood from someone specific in order to put it into someone else specific is the entire reason for introducing the trope.

With their quasi-premodern interest in the magic of transfusion itself, what these stories end up passing over is the intricacies of the modern blood trade and the intrusion of “the other” within that institution. By the 1930s, the norm in transfusions was blood bought from strangers (documented and traceable personages, but nonetheless people personally unknown to the recipient). With the emergence of blood banks in 1939, depersonalization and commodification became even more extensive, premised as the system was upon the storage and distribution of blood originating from anonymous donors. It is this segmented and quasi-industrialized structure that has created, socially and medically, both the greatest promises and the greatest problems for blood in the twentieth century. The conceit of most comic book transfusions – the medical fiction that blood carries attributes of a person’s personality that are replicated when transferred to someone else – was a superstition that the medical industry had to fight hard against in establishing a workable system of blood collection and distribution, especially with regards to overcoming fears about donors’ race and class. Isolated to the surgery room, transfusion looks like a form of reanimation or spirit possession. But when integrated as part of a wider blood industry, more socially complicated figures begin to appear.

It was, of course, very easy for blood banks to be appropriated by the horror genre, thanks to the central figure of the vampire. Across the world, “vampire” has been a common epithet for for-profit blood banks preying on the poor, whether those leeching America’s skid row or, in later years, industrial plasma centers in the Third World. “Bloodsuckers” and its variants were not so common in the Japanese literature on blood banks, but, as Mizuki’s manga shows, it was just as easy for Japanese to make the connection. Granted I haven’t dug very deep, but the earliest comics that I have seen that take up blood banks with a modicum of social commentary were made, not surprisingly, by the artists at EC Comics. With their eyes always open for real life horror, and with their offices in the Bowery at 225 Lafayette Street, it would be more curious had blood banks not appeared in EC titles.

When other horror comics from the 50s took up blood, they did so only to continue with the transfusion trope. See, via the Polite Dissent site, Syd Shores’s “I Prowl at Night!” (1952), where a man is unknowingly transfused with the blood of a werewolf he has accidentally killed with his car, and then passes it on to his own wife, or Lou Cameron’s “One Door From Disaster” (1954), where a whole body transfusion with banked blood fails to cleanse a woman of vampirical contagion. Once a godly miracle, transfusion is now either a false solution or a diabolical disaster, though this shift probably reflected genre conventions more than changing public opinion with regards to the blood supply, which at the time was swiftly going down the tubes (for anyone interested in the topic, I recommend Douglas Starr’s or Kara Swanson’s books, cited below in the comments section).

EC Comics, in contrast, and in full accordance with developing stereotypes, located horror not within medical science itself, but instead within the segmented system of buying, storing, and selling that is blood in the age of banking. The problem with the blood trade, as many people saw it, was that there were too many non-medical people involved and thus too little medical ethics to check market greed. Hence, a horror of blood middlemen.

First is Jack Davis and Al Feldstein’s “The Reluctant Vampire” (Vault of Horror, no. 20, 1951). Its star is a night watchman at a city blood bank. His name is Mr. Drink. As a vampire, he finds the job maximally convenient, for it provides him a supply of sanguine nourishment minus the trouble of going out and murdering innocents. He covers his tracks by doctoring the books at night. But then one night, the books are missing. “What’ll I do?,” screams Mr. Drink. “They’ll find out that blood is missing . . . and I’ll be exposed!”

He does his best to replenish what he’s taken with a spree of killing and bleeding. But it’s not enough. “Ladies and Gentleman,” announces Mr. Cross, the bank’s manager, at a staff meeting, “unless this center takes in twice the amount of blood it has been taking in, the home office is going to close us up.” This worries Mr. Drink, for closure would mean having to go back to bona fide vampiring. So he decides to continue emptying men of their blood, at least until business is stabilized. “I’ll just take little for myself. The rest, I’ll put in the blood bank . . . and change the records.” Mr. Drink so successful that the army (ignorant of the real reason for improved business) awards Mr. Cross a medal for his hard work and patriotism.

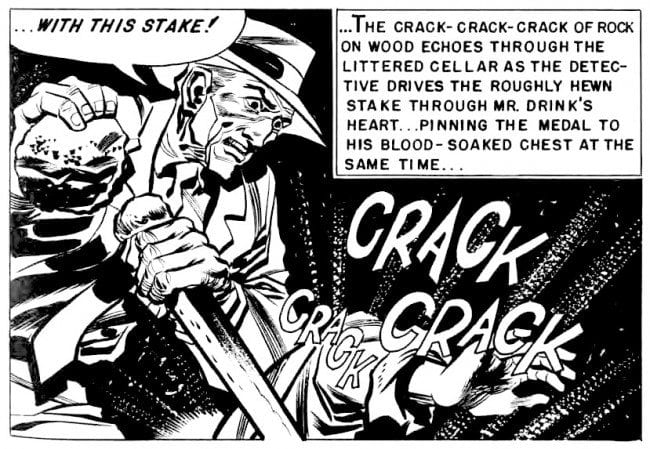

But once again Mr. Drink goes overboard. A company secretary notices that the bank’s inventory inexplicably increases after closing hours. When she hears news reports of vampire-like murders, she puts one and one together. The manager decides to inform the police. “This medal belongs to him. He doubled the blood donor center’s record, not I,” explains the manager as they stand around Mr. Drink’s coffin. “Well, lay it on his chest, Mr. Cross,” says a police detective, and proceeds to, CRACK CRACK CRACK, pin the prize to the diligent watchman’s heart using a fat wooden stake.

If Davis and Feldstein hint indirectly at unethical behavior in urban blood banks, the matter is explicitly treated in Graham Ingels’s “Pickled Pints” (Vault of Horror, no. 29, 1953). It too ends up a vampire tale, but that feature only appears suddenly on the final page. The rest of the story is a dramatized dialogue around the worst abuses of the blood industry, which by the early 50s was beleaguered by medical, legal, and social problems. Ingels apparently thought them gruesome enough to pass as a horror story nearly unadorned.

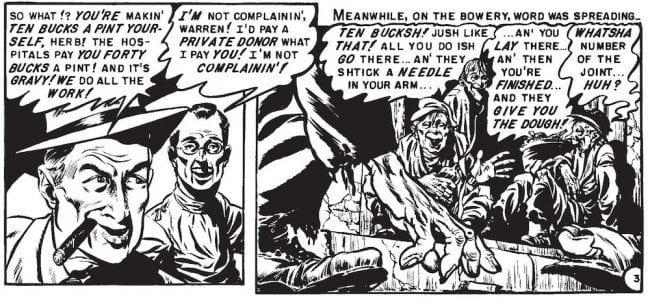

“Pickled Pints” begins with a literal depiction of “ooze-for-booze.” A Bowery bum stands staring into a bar window at someone’s tantalizingly bubbly glass of beer, when suddenly a well-dressed man grabs his shoulder and says, “How’d you like a drink buddy?” He clarifies, “I’m not offerin’ you a drink. I’m offerin’ you the chance t’make ten bucks so you can buy your own. No catch! It only takes a few minutes! All you have to do is become a blood donor.”

Blood-for-beer here, however, is of the lowest kind. Though blood was a relatively organized and respectable trade in the United States in its earliest years in the 1920s, supporting the image of the professional donor as a stalwart and charitable man, things became complicated during the Great Depression. Commercial agencies serving as middlemen between donors and hospitals mushroomed in the early 30s, causing conflicted feelings within the medical establishment. Hospitals and patients needed these agencies to secure an adequately large supply of blood, but they also knew that their business methods could be questionable and their hygienic standards low. This, the blood trade brought low by unmonitored market economics, had by the late 30s begun to ensconce, as the stereotypical image of the “professional blood donor,” the human failure whose only means of survival is selling his blood to medical crooks.

Thus, by Ingels’s time, the blood trade suggested nothing more than opportunities for hypocrisy and exploitation. The story continues: “The Bowery derelict had climbed the rickety stairs of the ancient loft building and knocked on the scarred and battered door.” Behind it, he finds another “alcohol-saturated character” like himself, laid out, exposing the holes in the toes of his shoes, making an easy ten’er by having a pint of his blood siphoned off. The Old Witch, a host akin to EC’s more famous Crypt Keeper, informs us that, as “everyone knows,” ten bucks a pint is a scam, because the private blood banks pay thirty to forty. Those places, however, won’t officially buy from the unhealthy. But in “Pickled Pints,” they are more than happy to get around medical ethics by buying bottled pints at a discount rate from flophouse bleeders in the Bowery. For Ingels, even legitimate blood banks get scare quotes around their “legitimate” status.

The gig begins to unravel when the bleeders get greedy. Another drunk comes in. They agree to buy a pint from him, but when he passes out while giving the first, they squeeze him for a secret freebie second. While they are doing this, the bum dies. Word gets out. No one will sell to these blood buyers anymore. The drunks value their lives more than easy booze. So what do the crooks do? They begin assaulting men on the street, far more eagerly than had Mr. Drink. They knock them cold, then drag them up to their loft to bleed them of a pint or two or three before they come to. As in “The Reluctant Vampire,” the blood trade not only exploits the urban poor, it attacks and kills them.

One night, after a day that saw the voluntary sellers dwindle to one, the crooks see a door open on another floor of their building, which they thought was entirely abandoned. They find inside a ragged man sleeping in a coffin. “We certainly didn’t have to travel far for our first sucker of the evening,” they kid, and lift him out of his cradle and up to their room. But this first sucker is also their last sucker, for he is actually, surprise surprise, a sleeping vampire. The sun sets as they set him on their operating table. When we wakes up, he sucks the metaphorical vampires dry. Serves them right, is the moral of the story.

I’d hazard a guess that, though he worked not a stone’s throw away from the Bowery, Ingels didn’t have a deep understanding of Skid Row economics. When the bums in “Pickled Pints” get addicted to the easy money, Ingels’s evil physician worries that some have starting coming as much as three times in a single month. In real life, that would be nothing. I’d guess ten or twenty pints before a hack doctor started feeling an itch in his conscience. But details aside, the basic picture holds: the blood industry is filled not only with vampires, but lowlife vampires who prey on the poor.

To my knowledge, Mizuki did not know these American blood bank comics. That doesn’t matter. It’s not like a seedy blood trade was an American monopoly. In fact, the situation in Japan was far worse. And it was close enough to many manga author’s lives, including Mizuki’s, for its horrors to be as much personally lived fact as imagined fiction imported, EC style, from society’s other half.

Let’s get into some history. You might find what follows overkill on the non-manga side, but it’s important for context. Before celebrating this or that artist for their representations of Japan’s dark side, one needs to have a feel for what that society was actually like. I want to avoid the Tatsumi effect, where intensity of experience (especially negative or degenerate experience) and extremeness of expression ends up being read as hardcore realism and naked authenticity. There is a difference, after all, between sensationalizing tabloids and gritty nonfiction.

(cont'd)