This letter by Harvey Pekar appeared in The Comics Journal #133 (December 1989):

R. Fiore has written a reply [“Funnybook Roulette,” Journal #132] to my article [“Comics and Genre Literature”, Journal #130] riddled with more mistakes than Swiss cheese is with holes (hurray, a metaphor!). I could fill a book just correcting his misrepresentations of my beliefs. He attributes statements to me that I did not make or come close to making, and don’t believe.

Among them are these: “What I find most offensive is Pekar’s assertion that the (moderate) success the Hernandez brothers have earned must somehow have been gained dishonestly. To accuse them of pandering...” blah blah. He says I assert — not imply but assert — this, when I don’t do anything of the kind, and actually have stated, at the end of my introduction to his The Reticent Heart, that Gilbert is a very ethical guy. Fiore also claimed that I made “the ridiculous assertion that serious cartoonists ought to eschew exaggeration and only draw realistically.” Again, Fiore lies. I merely claimed that realistic drawing is usually more appropriate for my stories. In my other Journal articles, I’ve praised the work of many “cartoony” cartoonists, including R. Crumb, David Boswell, Elzie Segar, Winsor McCay, J.R. Williams, Gene Ahern, Bill Griffith, and Gilbert Shelton, just to begin a list. And I’ve worked with cartoony stylists Crumb, Frank Stack, Chester Brown, and Stephen DeStefeno, among others.

Another lie Fiore tells is that “Pekar is trying to create a definition under which the only true literature is realist and any deviation from realism is acceptable only if it serves explicit (and none too subtle) didactic purpose.” In fact, in my article I refer to “great non-realist fiction.” That means I consider some non-realist fiction great, Fiore, you dolt. I wrote a lot about realistic literature because I was responding to Leon Hunt’s article “Pekar and Realism” (Journal #126). Hunt attacked realism and I reacted by defending it, but I said at the end of my article that I was in favor of “not just realistic comics, but surrealistic, impressionistic, expressionistic [comics], anything as long as it’s not the kidstuff that dominates the market today.” What I really dislike, then, are cliché-ridden comic book stories. It just so happens that in the comics context most cliché-ridden comics are non-realistic comics, so I was critical of them.

Fiore fancies himself as some sort of gunslinging intellectual, but actually he’ll have to learn a lot more to realize he’s ignorant. He also has the reading comprehension ability of a retarded first-grader, and tends to ignore statements that don’t agree with his fixed-in-concrete notion of what my views are. This causes him to believe that the only literature I like is stuff that resembles what I publish. If he hadn’t been so blindly prejudiced against me, he’d have realized that I enjoy and approve of a wide range of writing styles. Actually, I anticipated a great many of his complaints, but he ignored what I said, so anxious was he to complain about what he erroneously thought I said. Fiore gets livid when anyone criticizes his hero, Art Spiegelman, as I did.

I wonder how many times Fiore deliberately didn’t tell the truth. I should be generous, perhaps, and attribute some of his incorrect statements to stupidity. And ignorance.

Let me point out some of Fiore’s glaring errors. He concedes that I am correct when I label Animal Farm an allegory and Maus a biography/ autobiography, but he wants desperately to find some fault with me so he takes umbrage at my statement that Orwell didn’t “explicitly” (that was my word) identify the pigs in it. He then goes on to claim that Napoleon is Stalin and Snowball is Trotsky. To have identified these pigs explicitly then, Orwell would’ve had to call them Stalin and Trotsky, not Napoleon and Snowball. So Fiore is wrong again. Too bad he doesn’t know what “explicit” means. Animal Farm is an allegory based mainly on the Russian Revolution, but does not parallel it in every detail. Napoleon has a lot in common with Stalin, but in certain ways he’s also reminiscent of Lenin. Like Lenin, he leads the Revolution. Stalin did not lead the Bolshevik Revolution. Fiore claims Animal Farm parallels the Russian Revolution so closely that it’s “less an allegory than an expose of it.” However, Orwell biographer J.R. Hammond has stated that “it would be too simplistic to interpret Animal Farm in terms of a satire on the Soviet Union,” and quotes Orwell as writing that “the book was intended as a satire on dictatorships in general.” Fiore, of course, is simplistic. But perhaps he hasn’t read the book lately.

Fiore’s defense of Art Spiegelman’s portrayal of Poles as pigs in Maus is nonsense. He tries to come up with a two-part, cover-your-ass strategy. First, he implies that Spiegelman might have wanted to portray Poles as pigs because pigs are fairly intelligent. He says that’s why Orwell portrayed revolutionary leaders as pigs. Then he turns around and claims that if Art Spiegelman really had it in mind to portray Poles in a bad light, Art would be justified because Jews were treated badly in Poland. He claims I’m unwilling to “truly examine” the position of Jews in Poland.

Hey, Fiore-the-toilet-tongue, I happen to be a first-generation American Jew. My parents, aunts, uncles, and some of my cousins were born in Poland. I was raised on stories of the suffering Jews there. I heard them during the Second World War, before Spiegelman was born. My relatives remaining in Poland were virtually wiped out; only a few survive. Yet here is Fiore lecturing me about Jewish life in Poland. He probably goes to Watts and tells people there what it’s like to be black.

I’m far more aware than Fiore of what Jews had to put up with in Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe, including the Ukraine, where Jews were treated worse than in Poland. (Look up Bogdan Khmielnitsky and Simon Petlyura, Fiore.)

Orwell didn’t portray the leaders of the animal revolution as pigs just to praise their intellects: he wanted people to view them as coarse and greedy, which is what people usually mean when they call each other “pig.” Some Polish Americans, including Bill Sienkiewicz, were offended by Spiegelman’s portrayal of Poles as pigs.

And Spiegelman didn’t want to praise the intelligence of Poles by showing them as pigs any more than he wanted to praise the physical grace of Germans by showing them as cats. If Spiegelman had wanted to compliment Poles he would not have disingenuously told Carole Sobocinski he pictured them as pigs because they ate a lot of pork. Maybe I’ll write an anthropomorphic story and cast Fiore as a pig and leave it to him to figure out what I mean. Perhaps people have been calling him a pig for years and he’s been thanking them for complimenting his intelligence.

There is no excuse for Spiegelman’s stereotyping of Poles. Certainly Jews were persecuted in Poland, but not all Poles hated Jews — some risked their lives for them. As I said earlier, the doctrine of collective guilt, which Fiore justifies, leads to an exacerbation of ethnic hatred. In stereotyping Poles, Spiegelman uses a tactic that’s been turned against Jews, a tactic that cannot be condoned.

The reason, incidentally, that Spiegelman shows Poles hiding Jews from the Germans is because he has no choice. It’s an integral part of his father’s story; Poles sheltered his father and mother for a time. Spiegelman isn’t 100 percent accurate with his metaphors. Thus, he shows Jews who collaborated with Germans in persecuting other Jews as mice, not cats. Spiegelman’s oversimplification in using anthropomorphism works against him in various ways.

Fiore worshipfully accepts everything Spiegelman says. He believes it when Art claims he’s too sensitive to portray humans rather than cats and mice in the Holocaust situation. I don’t believe this claim, though. Art uses human characters in a story about his mother’s suicide. He prints violence-filled stories in RAW. He provides a detailed description of mass cremation in Maus’ eighth chapter.

Fiore spends a lot of words complimenting the Hernandez brothers without really coming to grips with what I said about them. I like their work, but I think their stories are somewhat sugar-coated and some of their women characters idealized. I answered a letter writer (Journal #132) who claimed there were plenty of women walking around just like Maggie and Hopey: “You say you know plenty of women floating around just like Maggie and Hopey? Women as flawlessly good-looking (before Maggie put on the extra pounds)? Women as vivacious? Women who are rocket ship mechanics? Women whose aunts are wrestling champions? Women who play in punk bands? Women who know the richest man in the world? Wow! That’s some neighborhood you live in.” Maggie and Hopey are obviously romanticized characters.

Pipo and Tonantzin also look too good to be true. (Some of Gilbert’s other women characters are also beautiful, although not perfectly so. Thus, Luba’s bust is disproportionately large and Carmen is very short. Both have lovely faces, though.)

The standard of living in Gilbert’s Palomar, based on such things as how the houses are furnished, is more reminiscent of a respectable working class American community than a tiny Mexican or Central American village. Fiore, groping for something to say (as usual), claims that I’m being condescending to the Third World people (!) when I point this out. Does Fiore actually believe the bullshit he writes? Well, assuming he does, I should point out that I went over novels by Latin American authors including Fuentes, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Asturias, Rulfo, and Yanez before writing about Gilbert’s Palomar. Not all of their books were depressing, but the people in all of them seemed to have a much lower standard of living than their rural and working class U.S. counterparts, including the people in the books of magic realists Asturias and Garcia Marquez. Does Fiore consider all of these writers condescending for portraying the lives of their countrymen more accurately, from an economic standpoint, than Gilbert does? I object more to the idealization and sugar-coating in Love & Rockets than to the fantasy. It’s possible to write fantasy and not romanticize or genericize people or places, as Dan Clowes’ recent Eightball comics illustrate.

I mentioned that Luba was a “hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold type, even though she’s a banadora, not a hooker.” Fiore notes that “he [Pekar] catches himself in time to notice she’s not a hooker.” Then, however, he goes on to criticize me, saying, “In the Palomar stories, Luba doesn’t fuck for money and isn’t particularly loving. Other than that it’s a perfect match.” So, he implicitly criticizes me for calling Luba a hooker even though a couple of sentences earlier he concedes that I say she’s not a hooker. What an incompetent Fiore is! He can’t remember what he’s writing from one minute to the next, so anxious is he to bad-mouth people. Veteran Journal staffers tolerate him, unfortunately, partly because most of them, and Journal readers, skim over his writing as carelessly as he’s skimmed mine.

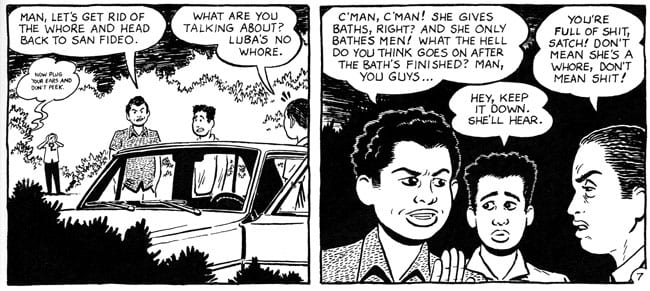

Fiore also claims that Luba’s emotionally distant and a neglectful mother. If you read Gilbert’s The Reticent Heart collection, however, you’ll find Luba repeatedly expressing concern over her kids. And here’s what Heraclio says to Luba one night: “Good old Luba. You’ve probably taken more shit than anyone in this town of Neanderthals. Guys are always bugging you and shit, women with their damn gossip. You’ve got more guts and tolerance of anyone I know, Luba. Why do you stay in Palomar? What’s in it for you?” In the story “The Reticent Heart,” Satch wants to ditch Luba: “Man, let’s get rid of this whore and head back to San Fideo.” Jesus defends her: “What are you talking about? Luba’s no whore.” Satch counters: “She gives baths, right? And she only bathes men! What the hell do you think goes on after the bath’s finished?” Jesus defends her: “You’re full of shit, Satch! Don’t mean she’s a whore, don’t mean shit!”

So, Luba is described as tolerant and brave, rough on the outside, the target of vicious gossip, but, as her defense of the retarded Martin in “Act of Contrition” illustrates, more willing than most Palomar residents to “do the right thing.” In other words, she’s a hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold type. (Type, Fiore, for the umpteenth time, I didn’t say she was literally a hooker.)

Fiore thinks I shouldn’t compare Spain and the Hernandez brothers. But it serves my purpose to do so in order to illustrate areas in which I think the Hernandezes can improve. Fiore tries to give the impression that I’m unaware of the fantasy element in Spain’s work, ignoring the fact that I begin a sentence “Spain doesn’t always write heavyweight realistic stories...” I go on to mention that when Spain does write biographical and autobiographical stories, his characters are more individualized and believable than the Brothers’ because he doesn’t romanticize and idealize them as much. Spain emphasizes action rather than psychological analysis, but his description of working class youth in the 1950s is very accurate in terms of dialogue and graphic content. Spain obviously read and was influenced as a kid by ‘40s and ‘50s adventure comics and genre literature, as have the Hernandez brothers, but now takes them less seriously, as the satirical Trashman and “Wilfred Kreel. Seeker of the Strange” indicate. Like Jack Cole in Plastic Man, Spain makes fun of straight comics. He certainly satirizes them more than the Hernandezes.

Now let’s examine Fiore’s charge that I made the “assertion” the Hernandez brothers are gaining popularity “dishonestly,” that they are “pandering.” Fiore’s charge is totally false; I never talked about pandering. I think, in fact, that there is a lot less literary pandering going on than is generally suspected. Most authors write the kinds of works they like to read. If their taste coincides with a lot of other people’s, they become popular. I said that one reason the Hernandez brothers have the following they do is because their stories are “full of young and pretty women that their readers can fantasize about, full of young people of both sexes having adventures.” Obviously, this is part of the appeal of Love & Rockets. But Gilbert and Jaime just as obviously are trying to write the best stories they can write, and are not primarily concerned with making a lot of money. When discussing Gilbert in my introduction to The Reticent Heart, I say, “The humor and sensuality in his work have been praised, but don’t overlook his compassion, his ethical sense.” I don’t think, despite disliking his work, even Frank Miller sells out. He believes the stuff he’s doing is good; he probably thinks it’s socially beneficial, too. I disagree, but I don’t question his honesty. Similarly, the Hernandezes, like a lot of comics illustrators, enjoy drawing pretty women (and, like a lot of comic book fans, looking at them) and would do so even if Love & Rockets wasn’t popular.

Another example of Fiore’s sloppiness: he tries to prove that Spain Rodriguez was as popular during the ’70s as the Hernandezes are now by claiming that comics like Young Lust and Zap sold a lot. Fiore’s mistake here is in not realizing that I didn’t compare Spain’s popularity in the ’70s to the Hernandezes’ now. I compared the Spain of today to the Hernandezes of today. I wrote, “So why do today’s comics fans praise the Hernandez brothers so much and ignore Spain?” Fiore also conveniently overlooks the fact that Spain was not the most popular cartoonist contributing to Young Lust and Zap — guys like Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, and Bill Griffith were. Also, the Hernandezes have published far more issues of Love & Rockets than Spain has solo books; their overall sales have to be much higher than his. Convention promoters have never knocked themselves out trying to get Spain to attend their affairs like they have the Hernandezes; obviously he’s never been as popular as they are now. I’ve known him since 1972, and he’s always had to scuffle to make a living. Fiore says, “While it can certainly be said that Spain’s work is undervalued, I can hardly see how the Hernandez brothers can be held responsible for that,” as if I were holding them responsible for Spain’s lack of popularity. But I didn‘t hold them responsible for this. I cited my reason for comparing Spain and the Hernandez brothers above; it had nothing to do with the Hernandezes denying Spain popularity. So, again, Fiore is wrong; again he sets up and attacks a straw man. He is obviously desperate to find something to complain about.

Fiore accuses me of incorrectly defining genre fiction, and says that, according to what I’ve written, Moby Dick, Lord Jim, and Pudd’n’head Wilson would all be considered genre fiction. He’s wrong. I claim that genre literature is cliché-ridden, commercial literature, and that among its categories are adventure (science fiction and fantasy, detective, espionage, horror, and cowboy) novels and romance novels. I claim that “genre novels rely for their appeal on contrived tricky plots, idealized protagonists, too-good-to-be-true heroines, and other stereotyped characters.” Fiore says he’s not satisfied with these comments and says that “genre fiction is fiction written according to genre conventions.” Yeah. And baseball is a game played according to baseball conventions. The point is to identify some of those conventions. I do, Fiore doesn’t. Actually, Fiore agrees with me as far as he goes, which isn’t very far. When I use the word “clichés,” I obviously mean the same thing Fiore does when he uses the word “conventions”; the words in this context are synonymous.

Moby Dick, Pudd’n’head Wilson, and Lord Jim are not genre novels because they are not cliché-ridden. Moby Dick and Lord Jim do have adventure elements and Pudd’n‘head Wilson, a humorous novel, has a mystery story element, but I never said genre novels could have nothing in common with fine art literature. Obviously, there are going to be similarities because many genre styles are derived from fine art literature.

Pudd’n’head Wilson deals with Mark Twain’s interest in the extent to which a person’s environment shapes him. Moby Dick is a profound philosophical and psychological novel that can be read on several levels. Lord Jim is primarily concerned with the psychological agony of its protagonist. Melville, Twain, and Conrad are also far too original stylistically to be considered genre writers.

If I described something as “big,” Fiore would scream that I should’ve said “large.” If I used “large,” he’d claim I should’ve said “big.” Fiore tries to nit-pick but he even stinks at that. His comments regarding what I said about the novel We are loaded with mistakes. He claims I should not have called it a science fiction novel. According to him, it’s a “dystopia.” And he says that it was written before the term “science fiction” was coined. Let me correct Fiore. The fact that We is an anti-utopian novel doesn’t mean it can’t be a science fiction novel. We takes place in a city of the future that has advanced technology. The protagonist is a rocket ship engineer. Obviously, We is a science fiction book. Novels can be more than one thing, e.g. they can be humorous science fiction novels. Zamyatin himself calls We a work of science fiction in the introduction to Pre-Revolutionary Russian Science Fiction (Ardis).

I referred to We as a fine art rather than genre science fiction novel because Zamyatin doesn’t employ the clichés that genre writers do today. Therefore it doesn’t matter that the group of clichés sf genre writers currently draw on had not yet been established in the early ’20s, when We was published, because I called it a fine art, not a genre, work.

The term “science fiction” had been coined long before We was published, contrary to what Fiore says. The Oxford English Dictionary cites it being used in 1851, although it did not become popular for some time after that. However, Jules Verne and H.G. Wells wrote what are now called science fiction books in the 19th century. In Harry Shaw’s Dictionary of Literary Terms, Lucian is cited as writing science fiction (about a traveler to the moon) in the second century.

Fiore claims that Zamyatin isn’t taken seriously by literary scholars. How would he know? Actually, Zamyatin is considered one of the greatest of a great group of Russian and Soviet novelists that emerged between 1900 and 1935. It’s possible to verify my opinion by reading Gleb Struve and Marc Slomin, recognized authorities on Modern Russian literature. In a 1946 review, Orwell called We a better book than Brave New World.

Other books by Zamyatin are in print and/or available to the general public, contrary to Fiore’s erroneous claim. Among them are A God Forsaken Hole (which I reviewed not too long ago for The Washington Post) and The Dragon, a short story collection.

Fiore makes the statement, “No great novel will ever be written under genre conditions,” as if that’s news to me. One of the reasons I wrote my article “Comics and Genre Literature” was to point out that most comics are too heavily influenced by genre literature. In other words, Fiore agrees with me, but is too dense to realize it. Nevertheless, he praises genre-derived comic books by Frank Miller and Howard Chaykin in columns he’s written in the past few years, as well as even worse crap. He’s just a fanboy with delusions of grandeur.

Back to We: Fiore claims I think the only “true” literature is realistic. My praise of the sf novel We shows that he misstates my position. Zamyatin’s writing is subtle as well, subtle enough so that, although it’s obvious he’s against totalitarianism, critics aren’t sure whether his target in We was the U.S.S.R. or England, which he considered too regimented.

Maybe the stupidest of all the stupid things Fiore says is that I’ve made a big mistake by mentioning I told illustrators Gary Dumm and Greg Budgett I didn’t care which old movie they put on the screen of a repertoire theater in a panel of one of my stories. Fiore jumps on that to claim that I am not exercising sufficient control on illustrators, that no one knows who’s responsible for what’s in my stories. Think about that, readers. Was Fiore scraping the bottom of the barrel to find something to beef about, or what?

Well, I’ll clear things up. I write my stories using panels and balloons in storyboard style. I include directions to the illustrators regarding what the characters and backgrounds should look like. I talk to the illustrators and keep tabs on the stories as they’re being done to be sure I get what I want. I see roughs and pencil versions. I think those are sufficient safeguards. In the case of the story in question, I had made a decision: I decided that, since I’d worked with Gary and Greg so long and had confidence in them, it would be best to let them draw a scene from a movie that they enjoyed drawing. If they had chosen something inappropriate, there would’ve been time to make a correction. In this regard, Michael Gilbert in a Journal interview [way back in #84!] complained that I was too controlling.

I would not expect Fiore to praise my writing, but he can’t even describe it competently. He says that I describe characters in my stories with “an essay in a thought balloon.” Which characters would those be? I sometimes speak directly to readers about characters, but I don’t give complete descriptions of them in a single thought balloon. I use speech balloons to describe major characters sometimes, but spread them over more than one panel. And I certainly would not call my descriptions of them “essays.” To express political or philosophical ideas, I do use the essay in combination with narrative storytelling. That’s unique in comics, and I’m proud to be doing it. What’s wrong with essays? Doesn’t Fiore write essays? Some great novelists have combined essays and narrative forms, including Melville in Moby Dick, and Dreiser. Sometimes I feel essays are the most effective means to communicate my ideas. Is Fiore claiming essays shouldn’t be used in comics?

However, I very often eliminate the authorial presence and write sparsely-worded, non-didactic stories in which I employ ambiguity, e.g. I eschew punch lines. These pieces, which some people have called “Harvey Pekar stories,” are not liked by most comic book fans, who want stuff that’s more pat. Fiore apparently hasn’t noticed them, though. Even Leon Hunt and Donald Phelps, who I’ve criticized strongly, are sharp enough to notice that I use a wide variety of storytelling techniques. Phelps praises my “wise election to tell many sorts of stories.” A critic who missed such an obvious point might be considered beneath contempt. However, I am charitable; I have contempt for Fiore.

He also claims I don’t write compelling narratives. I think I’ve written compelling stuff, including “An Argument at Work,” “Awakening to the Terror of the New Day,” “Same Old Day,” and “Rip Off Chick.” Of course, if Fiore wants The Count of Monte Cristo or caped crusaders and winged warriors, he’ll have to go elsewhere.

Fiore claims the only reason I criticize Spiegelman and the Hernandez brothers is jealousy, that comic book artists who receive more acclaim than I do become targets of my wrath. Since Spiegelman wrote to Crumb and claimed that I was jealous of him, perhaps I’d better deal with this charge. I’ve already written, “If you detect irritation here because artists and writers I’m not crazy about are getting raves, your mind’s not playing tricks on you.” But that’s about it. I may be a mean guy, but I take pride in my criticism. I’d never write anything I didn’t believe or thought was trivial just to make someone look bad. My primary concern is to do good work. The subjects I’ve dealt with recently — such as the genre vs. fine art issue — are crucial in determining the direction in which comics evolve.

There are all sorts of comic book people who get more acclaim than I do. Why didn’t I criticize Alan Moore or Dave Sim or Crumb or Bill Griffith or Gilbert Shelton or Lynda Barry or Matt Groening? Why have I, in fact, praised some of them in print? I have solid reasons for saying what I do. Spiegelman is just an average writer. His attempts at humor are often strained and lame, e.g. “Ace Hole, Midget Detective.” His stuff is cold and sometimes pretentious. His ear is nothing special (maybe Fiore’s impressed with the way he transcribes dialogue from a tape). If it were, maybe he’d have his wife speak with the French accent she has. As for his sense of pacing or construction, it’s pretty conventional in Maus. All of the book’s chapters are constructed the same way, in fact: contemporary framing sequences begin and end them, with flashbacks in between.

There are a number of comic book writers whose work I like more than Spiegelman’s, but they didn’t write about the Holocaust. Art’s got a big reputation now, and perhaps his future work will sell because of it. But if he’d written a book five times as good as Maus about anything but the Holocaust, it wouldn’t have garnered him nearly the acclaim he’s gotten.

I’ll give him credit for synthesizing 20th century fine art and cartoon styles. He’s a good illustrator. But Maus was one of his most conservative efforts from a graphic standpoint. I’ll also give him credit for pulling together a good publication in RAW. And I’ve said right along that Maus is a good, if flawed and overrated, book, mainly because of Vladek Spiegelman’s compelling reminiscences. O.K.? I’ve never said his work had no merit.

Why have I been so persistent in criticizing his faults, then? Mainly because they are particularly repugnant to me. Spiegelman wants people to treat him with the sympathy Holocaust survivors get. In chapter eight of Maus, Spiegelman tells his shrink — a Holocaust survivor named Pavel — about his problems with his father. Pavel answers: “Maybe your father needed to show that he was always right — that he could survive — because he felt guilty about surviving. And he took his guilt out on you — where it was safe... on the real survivor.” So Art now has Pavel, his shrink, claiming he’s the real survivor — the survivor of Vladek Spiegelman. It’s disgusting to see how Art builds sympathy for Vladek and transfers this sympathy to himself in the contemporary scenes.

I don’t like Spiegelman exploiting his Holocaust-survivor’s-son position this way. But he’s not the only person I’ve been critical of. I don’t like the way I.B. Singer — not an especially good writer but an acclaimed one, in part because of his PR skills — hustles himself with his humble Jewish grandfather act. I’ve put him down in one of my stories and I’ll do it again if I get the opportunity. (I’m doing it here, as a matter of fact.) I’m persistent; I don’t state things and walk away. David Letterman is afraid to have me on his show because I repeatedly criticized his boss, G.E.

Jealous? There’s no reason for me to be jealous. I’m doing exactly what I want to in comics, and no one else is doing anything like it; they don’t want to. Their work owes more to traditional comics stories.

As for the Hernandez brothers, I notice a couple of people have been critical of them in the Journal letters column lately. Do you think they’re jealous of the Hernandezes? Crumb put down Jaime’s work. Is Crumb jealous? The Hernandezes put down some people in their Journal interview. Are they jealous?

Since Fiore’s questioning motives, let me question his. He’s obviously a guy who likes to feel superior by dumping on others. Maybe he’s trying to project his faults on me. When he has a disagreement with someone, he desperately tries to get the last word in, no matter how inane or irrelevant it may be and often is. He’s a know-it-all who assumes all others know nothing unless they’ve gotten their information from him. Unfortunately, he’s been getting away with his bullshit for years because most Journal readers are, in fact, so ignorant they can’t evaluate what he says. On the other hand, Fiore makes himself look stupid with his flippant dismissal of Leon Hunt’s article. I disagreed with a lot of Hunt’s ideas, but I respected him enough to deal with his comments. Hunt’s at least serious about what he does; he doesn’t just shoot off his mouth like Fiore, who didn’t come to grips with what Hunt wrote.

Speaking of wanting more recognition and attention, Fiore certainly does. Like I said, he thinks he’s some kind of gunslinger. He opens his reply to Dennis Worden’s letter [Blood & Thunder, Journal #132] with “Screw you,” and gets insulting with Robert Crumb in their letter exchange [Journal #s 123 and 125].

Well, Fiore, I’m giving you attention here and I hope you appreciate it. If you don’t, then — as you said to Crumb — “Fuck you.”

Continued: R. Fiore's response