On the site today: Leslie Stein brings it with Day 2 of her diary; Joe McCulloch takes us into the Week in Comics; and Sean T. Collins reviews Kramers Ergot 8.

No links today, just blathering:

If I was going to pinpoint something I’ve been interested in comics lately it’s something along the lines of sensuality and regularity. This is not a category of thing I’m looking to fill, but rather a tendentious link between different books. Last month I read, for the first time, Milo Manara (The Manara Library 1: Indian Summer and Other Stories, Dark Horse, 2011). Manara, as written by Hugo Pratt in "Indian Summer" is a kind exploitation fetish cartooning monster. He is both filmic in his attention to elemental detail (grass, dunes, fire) and some sort of classicist in his staging (Piero della Francesca with a sense of humor). Everything important seems to play out across a wide expanse, figures posed just-so to convey maximum narrative per panel. But it’s Manara’s line that counts the most It’s erotic in and of itself. There’s a frisson to it that is unmistakable – it functions like the literal air in a film, enhancing the mood. Everything in a Manara drawings is fluttering ever so much. This also extends to the ugliness of violence, sexual or otherwise. The women being raped by lithe youths or decrepit old men are always in some state of ecstasy. There’s no consequence, no horror at work underneath that shimmering beauty. And that’s where Manara and Pratt perform a kind of tripling. On the one hand, they are inviting you to participate in the crime, to get off on it and implicate yourself. On another they’re satirizing your revulsion at being aroused, and on another they’re simply tweaking 1970s Italian Catholic culture, fitting in just right with Dario Argento on the “Ok, just how serious is this” scale. Manara’s almost uncannily beautiful artwork raises it up to such an immaculate level of craft that it confuses the matter even further. It’s all so perfect, so un-comic book like, in the American sense.

If I was going to pinpoint something I’ve been interested in comics lately it’s something along the lines of sensuality and regularity. This is not a category of thing I’m looking to fill, but rather a tendentious link between different books. Last month I read, for the first time, Milo Manara (The Manara Library 1: Indian Summer and Other Stories, Dark Horse, 2011). Manara, as written by Hugo Pratt in "Indian Summer" is a kind exploitation fetish cartooning monster. He is both filmic in his attention to elemental detail (grass, dunes, fire) and some sort of classicist in his staging (Piero della Francesca with a sense of humor). Everything important seems to play out across a wide expanse, figures posed just-so to convey maximum narrative per panel. But it’s Manara’s line that counts the most It’s erotic in and of itself. There’s a frisson to it that is unmistakable – it functions like the literal air in a film, enhancing the mood. Everything in a Manara drawings is fluttering ever so much. This also extends to the ugliness of violence, sexual or otherwise. The women being raped by lithe youths or decrepit old men are always in some state of ecstasy. There’s no consequence, no horror at work underneath that shimmering beauty. And that’s where Manara and Pratt perform a kind of tripling. On the one hand, they are inviting you to participate in the crime, to get off on it and implicate yourself. On another they’re satirizing your revulsion at being aroused, and on another they’re simply tweaking 1970s Italian Catholic culture, fitting in just right with Dario Argento on the “Ok, just how serious is this” scale. Manara’s almost uncannily beautiful artwork raises it up to such an immaculate level of craft that it confuses the matter even further. It’s all so perfect, so un-comic book like, in the American sense.

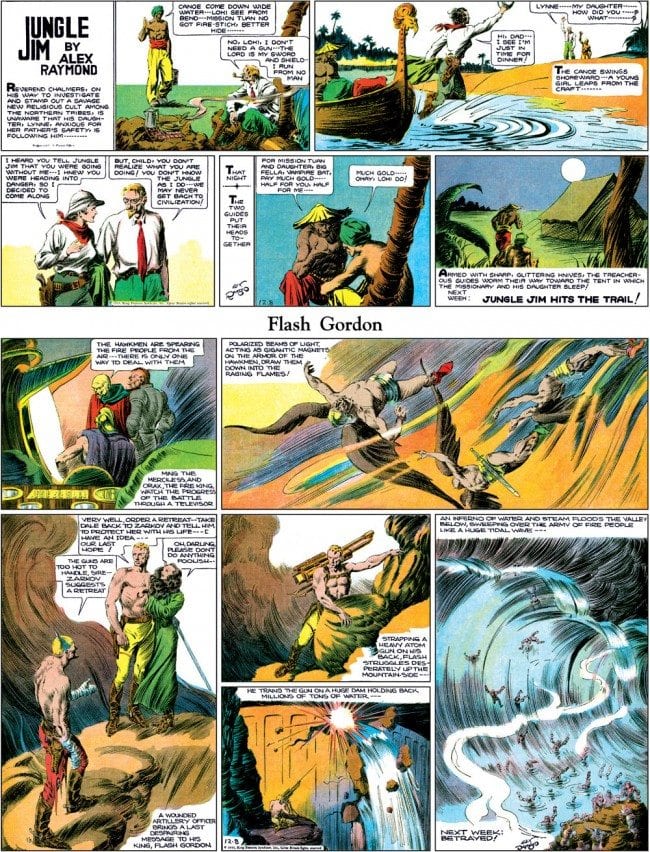

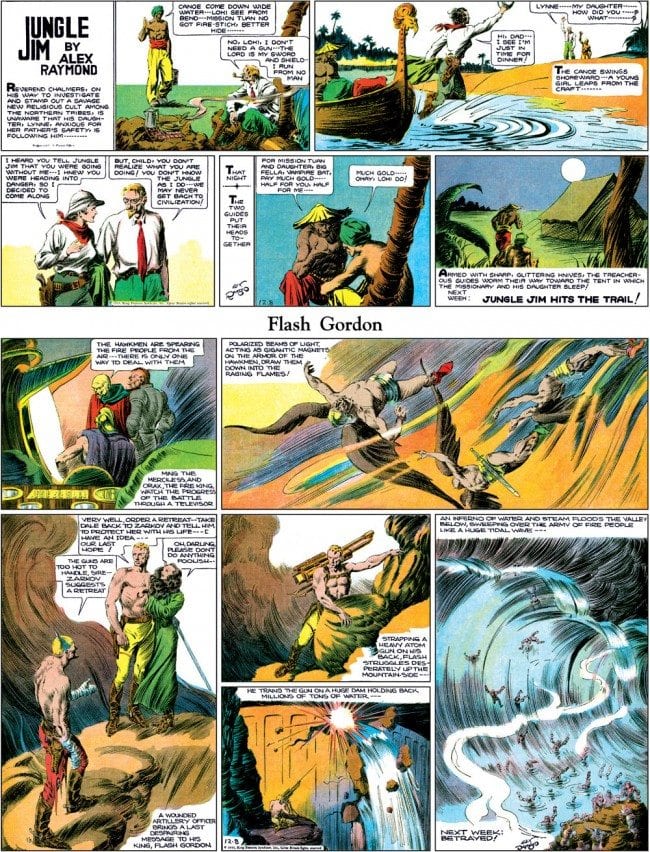

Speaking of which, I’ve also been spending some with Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon and Jungle Jim, 1934 to 1936 (IDW, 2011), which arrives with an introduction by Bruce Canwell that takes a startling weird turn very early on; he rightly assumes that most readers can do with just a gloss on Raymond’s life, which has been extensively detailed elsewhere. So instead he goes in depth on the life, writings, and contributions of Don Moore, who wrote Flash Gordon (usually uncredited) from sometime in the 1930s through the 1950s. Moore is one of those pulp-era characters about whom the more your read the shakier your standing might seem. Canwell does a great job of sussing out the very murky origins of comics, showing all the various factors at work, from genre-popularity to syndicate edicts to artistic ambition. It's a great and holistic examination. Canwell also gets at one of the primary frustrations of studying this stuff: For a lot of it we simply don’t know, and probably never will, for reasons of records, relative egos, and the status of the material itself.

The book begins with the first Flash strip, with Raymond still in a more standard adventure-comics mode: crude, muscular, a little cramped. We watch Raymond learn quickly on the job as he figures out how to make the fantasy work for him. During 1934 he goes from a cramped 12 panel grid, packing in far too much information per panel, to a 9 panel grid in which he seems to find his scale. By autumn he stops going for big scenes in each panel, and instead opens up the panel to focusing on figures alone. And in 1935 he’s using dynamic figures offset by well-composed plays of shadows and shapes; then in the summer the famously sensual Raymond lines come in (As an aside, I wonder what triggered all those lines? A chance discovery of William Blake? Virgil Finlay is more likely. Maybe Franklin Booth?) By the end of the year he’s down to as few as five panels per strip, each a full-fledged narrative illustration, and by 1936 he’s there, in his prime. The lines stand in for water, shadow, air, fire… anything elemental. There are few concretely delineated shapes – just forms described by swirling lines. Raymond can’t put a line down on the page without sexing it up. All those swooping lines, long, vivacious strokes.

No one would ever accuse him of subtlety, but more than anyone else he understood the sheer fleshiness of fantasy. Buck Rogers was more graphically inventive and schematically precise, but Raymond had sex on his side. He kinda had to make it that way, because he wasn’t much of a designer. The costumes, guns, creatures and planets are generic pulp stuff, with none of the sophistication of Calkins and later Keaton on Buck Rogers. Raymond’s Flash is the idea that it’s basically space-age Tarzan, or medieval space-age. Our hero is usually just in a swimsuit and a cape. Raymond makes no real attempt to invent – it’s all in the drawing. I like that, of course, and I can see why so many others did, too. In a lot of ways, Raymond is the crude version of Hal Foster, who was all restraint and, even when cutting loose, is classy. Not Raymond. When a damsel collapses at the villain’s feet, she falls into a vulnerable pose. She awaits ravishing. Every figure in a Raymond comic is doing something to another. No one just stands there. And in these strips lurks most of Frank Frazetta, all of Al Williamson, a chunk of Wally Wood, Bill Everett, and so many others.

This particular edition of Raymond’s Flash is not my first, but I would call it the best, short of seeing isolated black and white proofs reproduced in a few 1970s Russ Cochran tabloids. The repro here is superb, and having the topper strip, Jungle Jim, just above Flash is instructive. It foreshadows the close-quarters action Raymond would work with in Rip Kirby.

Y’know, there’s something to be said for these professionals. Manara is one of them, cranking out his stuff year in, year out (to the point of hack-dom, really). Raymond certainly did over there in Connecticut. So did Milton Caniff. I’m thinking about these guys these days maybe because they offer such solidity. They created complete bodies of work that, sure, contain pockets of mysteries, but mostly progress along fairly neat lines. Neither lived to see themselves displaced or forgotten (though Caniff’s politics embarrassingly fell out of step with his times). And that’s reassuring. There’s a finite quality there. McCay, Herriman… these guys died before they could be fully known. Not these others. It spills from the subject matter, too: Adventure – the dominent fan-supported comic book/strip genre from the late-1920s onwards. And why not? Deep in the depression it makes perfect sense to go for a ride, man. There’s been a spate of Caniff books lately, not least the complete Terry and the Pirates and, last year, Caniff: A Visual Biography (IDW, 2010). This was one of my, as the saying goes, favorite books of the year, because his visual autobiography is not so much what you might think -- paintings, diaries, secret stuff -- but rather his career, en toto. Caniff's art really is his comic strip work, and by extension the work that happens around the art: Ads, promotions, endorsements, etc. It's the stuff I always liked in Cartoonist PROfiles, the stuff the was necessary to be a good comic strip man. Caniff doesn’t stretch out or, to use a Santoro-ism, “riff”. His non-strip drawings are scenes of characters interacting, or gathering of characters, but it's not like he's telling you something new. You won’t learn something new about Caniff in the book, and that’s why I like it. Instead you have a perfect encapsulation of an immensely popular cartoonist's career work: It's the other stuff, and in sifting through 50 years of it one can see the artist and the world and industry change, all reflected in an imaginary teetering pile of paper.

Y’know, there’s something to be said for these professionals. Manara is one of them, cranking out his stuff year in, year out (to the point of hack-dom, really). Raymond certainly did over there in Connecticut. So did Milton Caniff. I’m thinking about these guys these days maybe because they offer such solidity. They created complete bodies of work that, sure, contain pockets of mysteries, but mostly progress along fairly neat lines. Neither lived to see themselves displaced or forgotten (though Caniff’s politics embarrassingly fell out of step with his times). And that’s reassuring. There’s a finite quality there. McCay, Herriman… these guys died before they could be fully known. Not these others. It spills from the subject matter, too: Adventure – the dominent fan-supported comic book/strip genre from the late-1920s onwards. And why not? Deep in the depression it makes perfect sense to go for a ride, man. There’s been a spate of Caniff books lately, not least the complete Terry and the Pirates and, last year, Caniff: A Visual Biography (IDW, 2010). This was one of my, as the saying goes, favorite books of the year, because his visual autobiography is not so much what you might think -- paintings, diaries, secret stuff -- but rather his career, en toto. Caniff's art really is his comic strip work, and by extension the work that happens around the art: Ads, promotions, endorsements, etc. It's the stuff I always liked in Cartoonist PROfiles, the stuff the was necessary to be a good comic strip man. Caniff doesn’t stretch out or, to use a Santoro-ism, “riff”. His non-strip drawings are scenes of characters interacting, or gathering of characters, but it's not like he's telling you something new. You won’t learn something new about Caniff in the book, and that’s why I like it. Instead you have a perfect encapsulation of an immensely popular cartoonist's career work: It's the other stuff, and in sifting through 50 years of it one can see the artist and the world and industry change, all reflected in an imaginary teetering pile of paper.

Some of that other stuff is also contained in Male Call (Hermes Press, 2011), which collects the entire strip Caniff drew from 1942-1946, distributed to military papers for stations all over the world. It’s odd to see this most macho of artists – all thick line and shadow and chunks of shape, take on sex. With Raymond it’s all in the contours and the organic lines of bodies. For Caniff it’s all “tee-hee” oopsy poses (Miss Lace fixing her garter; a waitress leaning forward with a drink), facial expressions and “whoah nelly” reaction shots. It’s unsubtle, sanctioned sexy. That’s not to say it’s not great cartooning. It actually really is, reminding me a ton of Harry Lucey’s 1950s Archie work, when Betty and Veronica were acting at their sexiest. This is a looser line than Terry, less grave, maybe faster.

Some of that other stuff is also contained in Male Call (Hermes Press, 2011), which collects the entire strip Caniff drew from 1942-1946, distributed to military papers for stations all over the world. It’s odd to see this most macho of artists – all thick line and shadow and chunks of shape, take on sex. With Raymond it’s all in the contours and the organic lines of bodies. For Caniff it’s all “tee-hee” oopsy poses (Miss Lace fixing her garter; a waitress leaning forward with a drink), facial expressions and “whoah nelly” reaction shots. It’s unsubtle, sanctioned sexy. That’s not to say it’s not great cartooning. It actually really is, reminding me a ton of Harry Lucey’s 1950s Archie work, when Betty and Veronica were acting at their sexiest. This is a looser line than Terry, less grave, maybe faster.

The other thing Caniff: A Visual Biography made me think of is that, like Raymond, no one gets hip points for liking Caniff. It’s not like Crumb was going on about the poetry of the 1940s Caniff line. No way. By the time the 1960s rolled around, younger artists were getting Caniff via EC Comics or, for that matter, the Lee Elias and Mort Meskin of DC SF titles. I also found the book curiously sad in a sense, because Caniff and his creation are so forgotten by the culture (non-comics) now. It's not like other great cartoonists whose work at least lives on through their characters (Popeye, Prince Valiant, Annie, et al), even if the protagonist obscures the artistry. Nope, Caniff's story, and his character's, is over. That's a strange thing. It's sealed in a way -- you can still see Snoopy, even if it signifies something else now. But Caniff and his tribe are frozen.

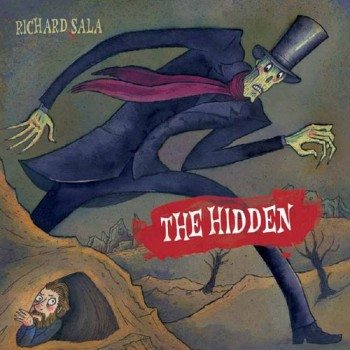

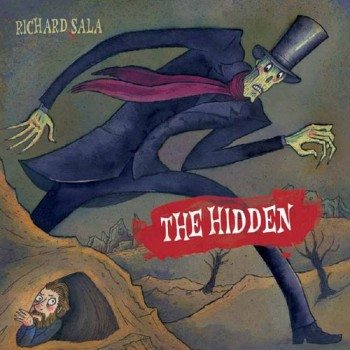

And for my last act, I have to pay homage to Richard Sala’s incredible and overlooked book, The Hidden (Fantagraphics, 2011). Sure we reviewed it here on the site, but I only just read it, and it’s really quite incredible. Sala’s kind of a pro himself, turning out at least a book a year (much like another visionary, Gilbert Hernandez), and this twist on Frankenstein reads, not unlike that gothic romance, as an allegory for artistic ambition gone wrong, or, maybe because I’m currently reading Simon Reynolds’ Retromania, like a tale of collector psychosis. Victor collects and then creates a monster out of various parts, that monster does the same, and, in the end, after killing his creation, Victor can't help himself, and saves just one last specimen -- collecting just one more thing to work on. Just one more project... It read to me like a story about making something that does harm, and perpetuates that harm, but taking such pleasure in the process of the making that it borders on self (or in this case, species) destruction. Yep, it's a gothic romance all right, and all the better for it. Sala's tale could not be any further from the mentality of the artists above, but somehow, Sala's lush visuals and perfect sense of pacing seems to dovetail with that work. It is a fully formed professional statement, even as it splits off into another comics world all together. It's there, I guess, that my thread really unravels.

And for my last act, I have to pay homage to Richard Sala’s incredible and overlooked book, The Hidden (Fantagraphics, 2011). Sure we reviewed it here on the site, but I only just read it, and it’s really quite incredible. Sala’s kind of a pro himself, turning out at least a book a year (much like another visionary, Gilbert Hernandez), and this twist on Frankenstein reads, not unlike that gothic romance, as an allegory for artistic ambition gone wrong, or, maybe because I’m currently reading Simon Reynolds’ Retromania, like a tale of collector psychosis. Victor collects and then creates a monster out of various parts, that monster does the same, and, in the end, after killing his creation, Victor can't help himself, and saves just one last specimen -- collecting just one more thing to work on. Just one more project... It read to me like a story about making something that does harm, and perpetuates that harm, but taking such pleasure in the process of the making that it borders on self (or in this case, species) destruction. Yep, it's a gothic romance all right, and all the better for it. Sala's tale could not be any further from the mentality of the artists above, but somehow, Sala's lush visuals and perfect sense of pacing seems to dovetail with that work. It is a fully formed professional statement, even as it splits off into another comics world all together. It's there, I guess, that my thread really unravels.

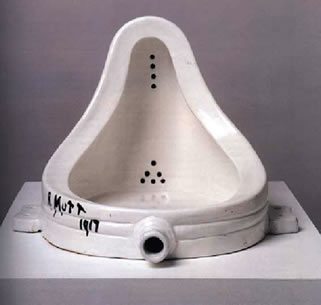

Marcel Duchamp, who is of course usually credited with starting the whole conceptualism business off, began his career as a gag cartoonist submitting panels to Parisian literary journals (have his cartoons ever been collected into a book? I'd love to read them), and comics historian M. Thomas Inge has suggested that the "R. Mutt" signature Duchamp scrawled at the bottom of his most famous "readymade" was an explicit reference to Bud Fisher's A. Mutt from Mutt and Jeff.

Marcel Duchamp, who is of course usually credited with starting the whole conceptualism business off, began his career as a gag cartoonist submitting panels to Parisian literary journals (have his cartoons ever been collected into a book? I'd love to read them), and comics historian M. Thomas Inge has suggested that the "R. Mutt" signature Duchamp scrawled at the bottom of his most famous "readymade" was an explicit reference to Bud Fisher's A. Mutt from Mutt and Jeff.